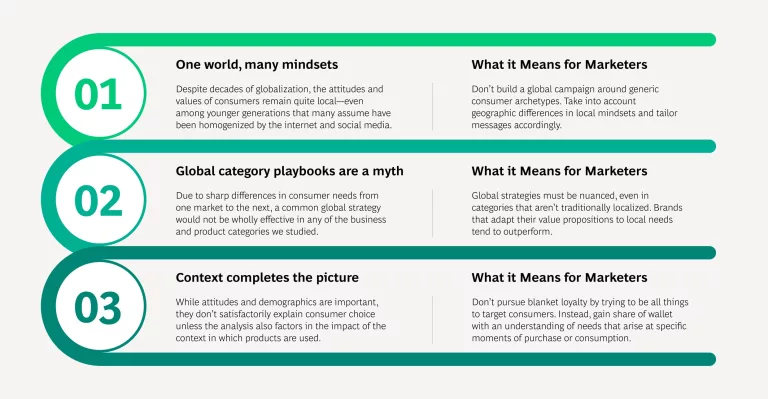

What really drives consumer choice around the world? An intensive BCG research project offers three key insights:

Rarely has navigating the global consumer market landscape been more bewildering. On top of the societal and technological changes that were already transforming markets, the COVID-19 crisis has rocked the world’s economies and left them in different levels of recovery—some still mired in recession, others apparently roaring back, and yet others in a state of confusion over whether the worst is yet to come. Clearly, however, this pandemic is a black swan event that is fundamentally shifting purchasing behavior in many product and service categories in ways that marketers around the world have yet to comprehend.

With trillions of dollars at stake, companies are employing the methods they’ve traditionally relied on to position their products and predict consumers’ spending habits in the new normal. They’re developing archetypes of target consumers by crunching demographic data and using surveys and focus groups to quiz people on a wide range of attitudes and sentiments.

The trouble is, such methods risk oversimplifying the dynamics that actually drive purchases. Most consumers around the world say they are value-conscious and willing to pay more for environmentally sustainable products, for example. Yet when asked to rank the factors that influenced their most recent purchase of anything from a garment to a beverage to a restaurant meal, they usually rank sustainability and value well down the list. And although “you are what you drive” is an automotive marketing truism, we found that several of the most influential factors in a car purchase have more to do with context—such as whether the consumer has ever bought a vehicle before—than with mindset.

A nuanced understanding of what really drives consumer choice can make the difference between dominating a category in a target market and making insufficiently thoughtful decisions about product, pricing, and positioning that leave value on the table.

To this end, Boston Consulting Group’s Center for Customer Insight (CCI) set an ambitious goal: to gain a deep understanding of consumer needs—and therefore choice—across a range of product categories in six major markets—Australia, China, France, Germany, Japan, and the US.

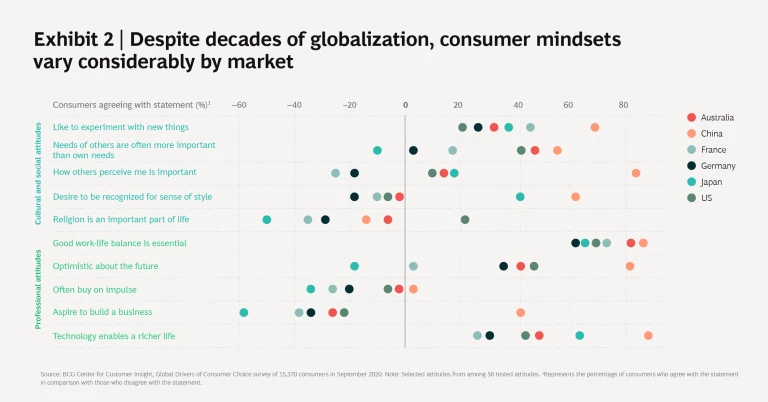

Our analysis of survey results from more than 15,000 consumers, taking hundreds of variables into account, yielded a number of insights that run counter to conventional wisdom. Despite decades of globalization, for example, we found that consumer mindsets still vary significantly in different parts of the world, including in markets that are generally regarded as similar. In fact, even though many marketers see millennials and Gen Z as important global segments, attitudinal differences from one market to another are just as pronounced among members of these younger generations as among their elders.

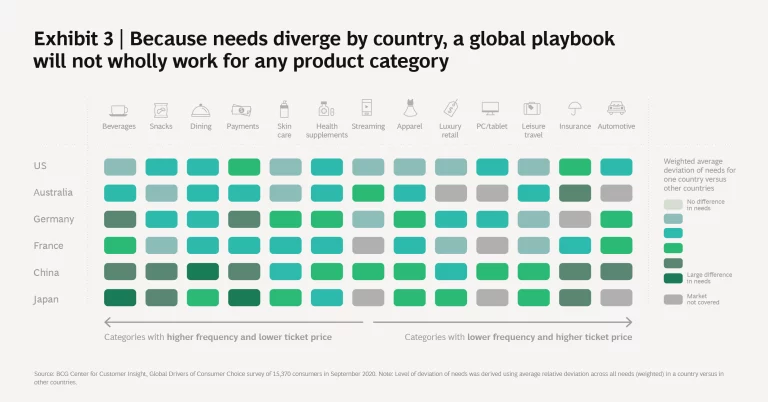

We also found that the idea that a brand can succeed by using a common global strategy to capture demand is a myth. In each business and product category we studied, we found that consumer needs differ so much from market to market that a universal global category playbook will not be wholly effective. Furthermore, our research revealed that attitudes and demographics, while important, do not on their own satisfactorily explain choice in any category. To be thorough and accurate, an analysis must also factor in the context of when, how, and with whom a product is used or purchased.

The challenge is to understand precisely which combination of factors—out of hundreds of variables—drives needs in specific categories in specific markets. To understand the influencers of consumer choice in a specific category country-by-country, companies must arm themselves with comprehensive research that combines an understanding of attitudes and demographics with an appreciation of context.

Companies need comprehensive research that combines an understanding of attitudes and demographics with an appreciation of context.

Identifying Drivers of Consumer Choice

BCG’s CCI has long been intensively studying consumer behavior and purchasing decisions in specific markets and used the firm’s Demand Centric Growth methodology to understand key drivers of choice. What we haven’t previously attempted is to analyze how the balance of three crucial dimensions—consumer demographics, attitudes, and context—applies across goods and service categories and across countries to influence consumer needs and, therefore, choice. (See Exhibit 1.)

In the fall of 2020, we launched a major study that will eventually cover 18 of the world’s most important markets. The first phase of this research focused on Australia, China, France, Germany, Japan, and the United States. In each market, we interviewed a representative group of consumers of various ages and income levels, asking them to identify their level of agreement with 56 attitudinal statements. We then asked them which key needs influenced their most recent purchase or consumption decision, as well as the context at the time of their most recent purchase or usage occasion, in 13 categories: beverages, snacks, dining, payments, skin care, health supplements, streaming, apparel, luxury retail, PCs/tablets, leisure travel, insurance, and automotive.

The principles of BCG’s Demand Centric Growth methodology enabled us to examine the impact of attitudes, contexts, and demographics on consumers’ needs for recent purchases or for product or service usage—and to conduct apples-to-apples comparisons of the influence of each variable. For this effort, we developed a rich understanding of consumer mindsets and drivers of needs in all 13 categories across countries and across generations.

One World, Many Mindsets

Insight 1: Despite decades of globalization, consumers’ mindsets remain highly localized.

Marketers have long known that consumers’ sentiments and values vary from one market to another. However, an increasingly popular narrative asserts that, due to globalization, Gen Z and other demographic groups are distinct segments that share similar attitudes around the world. We decided to delve more deeply into the degree to which various specific attitudes resonate in different countries and segments.

Consumer attitudes tend to be more different than similar from one market to the next.

Overall, we found that consumer attitudes tend to be more different than similar from one market to the next. Several clusters did emerge, however. We found a striking alignment between US and Australian consumers on nearly every attitude, such as their agreement that “technology enables a richer life” and the extent to which they are “optimistic about the future.” We also discovered a general alignment between German consumers and French consumers. US consumers differed most markedly from their counterparts in other Western nations on the high value they place on religion. (See Exhibit 2.)

Our research found a distinct East-West divide on most attitudes. Westerners exhibited greater individualism, expressing less interest in how others perceive their purchases or in how those purchases reflect on their sense in style. When we asked consumers to rank their most important attitudes, Westerners tended to agree strongly with the assertion that it is “important to be an individual”—a statement that resonated less in Japan and failed to make the top ten in China.

In many instances, Chinese consumers stood apart from all others in their attitudes. For example, they expressed by far the strongest optimism about the future and the greatest faith in the enabling effects of technology. In addition, 86% of Chinese consumers agreed that they care what others think about their purchases, which was not a major concern in the West. On privacy matters, such as whether they worry about the safety and security of their data, Chinese respondents stood out by giving that concern an unusually low ranking. In neighboring Japan, by contrast, respondents were the least optimistic of any country in our study, and they were unique in saying that they place a very high value on alone time.

Attitudinal differences among young consumers are just as distinct by country as they are for older age groups.

Much has been said about attitudes and preferences shared internationally by younger generations, such as millennials and people under the age of 30, owing to greater connectivity to the internet and to social media. So we were curious to see whether young adults held more uniform views around the world than members of older generations did. When we compared cross-country correlations of attitudes for sub-30-year-olds to those for all respondents, however, we found that the attitudinal differences among young consumers are just as distinct by country as they are for older age groups. Similarly, higher-income groups exhibit differences by market. This may indicate that global archetypes are exaggerated, and that it is risky to develop a broad strategy for a generational mega-segment without taking significant local nuances into account.

Global Category Playbooks Are Usually a Myth

Insight 2: A common global strategy would not be wholly effective in any of the 13 categories we studied.

Just as consumers’ attitudes differ around the world, so do their needs. This holds true not just for products commonly tailored to local tastes—such as beverages, snacks, and dining—but also for needs in the automotive, insurance, PC and tablet, and even payments categories, in which companies invest relatively little time localizing their offerings. (See Exhibit 3.) In only a few categories—such as leisure travel, luxury retail, and content streaming—did needs remain relatively similar across the globe. Supply could be the reason: Netflix, Amazon, and other streaming players offer very similar content around the world, usually with local translation or subtitles. In the case of luxury products, similarities in global needs may reflect demand for the signature nationalities of the products and brands purchased, as opposed to local customization. But even in such categories, which are exceptions, consumers in China and Japan expressed some distinct local needs.

Our findings imply that companies must understand demand locally. One-size-fits-all marketing strategies are unlikely to work globally for most business-to-consumer categories. Why, then, do some MNC brands succeed around the world? In part, we found, this is because some international brands are perceived differently in different markets and may even fill very different needs. For example, looks and public perception give BMW an edge in China, according to our research, while in Germany BMW’s advantage is its image for quality. Some Starbucks coffee shops in Japan resemble traditional teahouses, while in Mexico they often look more like bars. And while McDonald’s uses a standard operating model and supply chain around the world, it constantly adapts its menu to local tastes, offering vegetarian Big Macs in India and peasant soup in Portugal, for example.

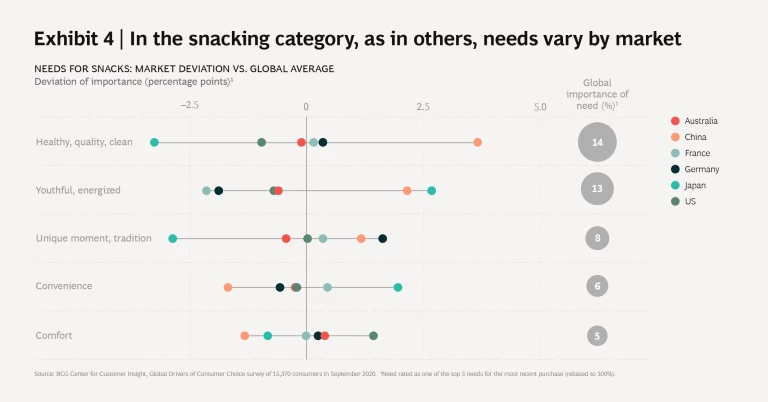

We can understand this dynamic better by diving a bit deeper into one category: snacks. Chinese consumers cite a much higher need for health and quality when purchasing a snack than do their counterparts in the other markets we studied. Japanese consumers, for instance, attached a higher importance to “convenience” when snacking. Clearly, companies should not take localization lightly in the snacking category. (See Exhibit 4.)

Context Completes the Picture

Insight 3: Although important, attitudes and demographics don’t satisfactorily explain choice unless the analysis also factors in the impact of the context in which products are used.

Our research found that attitudes and demographics often do not directly manifest themselves as drivers of needs in actual purchases and consumption. Context plays an important role in influencing the tradeoffs that consumers make at the moment of purchase or consumption.

This dynamic became clear when we compared the values and sentiments that respondents told us are important to them with the factors that specifically influenced their most recent purchases or usage occasions. For instance, many consumers around the world said that value consciousness is very important to them—as one might expect, given the great economic uncertainty created by the pandemic.

Value consciousness as a general mindset has little correlation with the role that value plays in actual purchasing decisions.

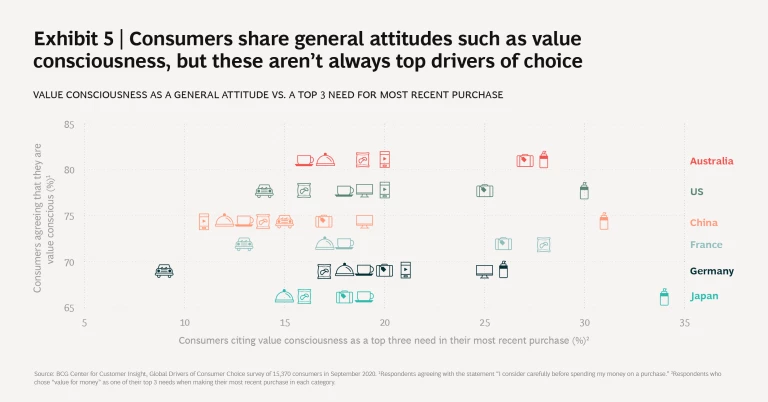

Except in a few cases, however, our research found little correlation between value consciousness as a general mindset and the role that value played in actual purchasing decisions. While consumers in each of the six countries agreed that value consciousness is an important consideration—ranging from 67% in Japan to 81% of Australia—a much smaller minority cited value as one of the three leading needs in their most recent dining, snacking, beverage, auto, PC, or video streaming purchase. For instance, although nearly 70% of German consumers said they considered themselves to be value conscious, less than 9% of them viewed value as being a top-three need in their latest automotive purchase, and only 25% considered it a top-three factor in their most recent PC or tablet purchase. (See Exhibit 5.)

The same holds true for environmental sustainability. A majority (52%) of all consumers interviewed in the six countries agreed with the statement, “I buy environmentally friendly products, even if more expensive.” But when we asked consumers about the motivations behind their most recent apparel purchase, sustainability ranked 14th.

These findings do not mean consumers don’t care about value or environmental impact. But when balanced against the many other factors they weigh when actually making a purchase, these needs are often too weak on their own to sway a decision—although they may act as tie breakers when other needs have been satisfied. The challenge is to understand what other factors influence the tradeoffs that consumers make.

Changes in context often influence the ways consumers fulfill their needs. As an illustration, think of an office worker who lives with a spouse and two children. The worker may stop at stores a few times a week on the way home to browse for apparel or pick up household supplies. Forced to work from home and spend more time with the family because of the pandemic, the worker now satisfies a need for convenience in different ways, such as by shopping more online.

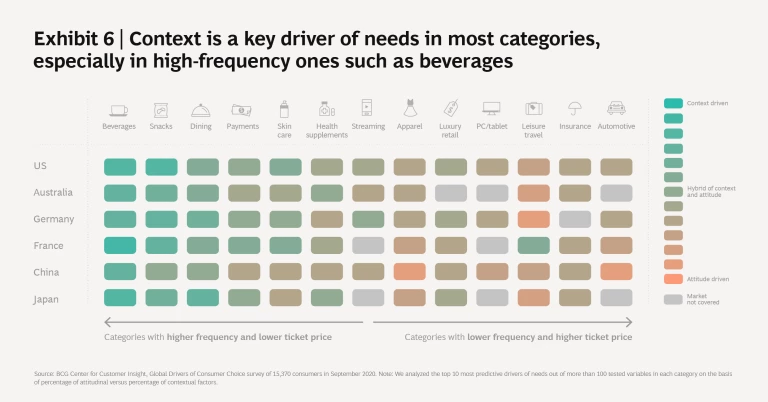

We analyzed more than 130 variables to identify those that drove the greatest variations in consumer needs and, therefore, choice. We found that context can play a dominant role—often outweighing attitudes—in high-frequency, modest-cost categories. Restaurant purchases and beverage and snack consumption, for example, are highly context-driven in all the markets we studied. While consumers may find a certain restaurant’s brand image appealing, the choice of the restaurant they actually order from depends largely on the people they are with, the time of day, and the occasion. (See Exhibit 6.)

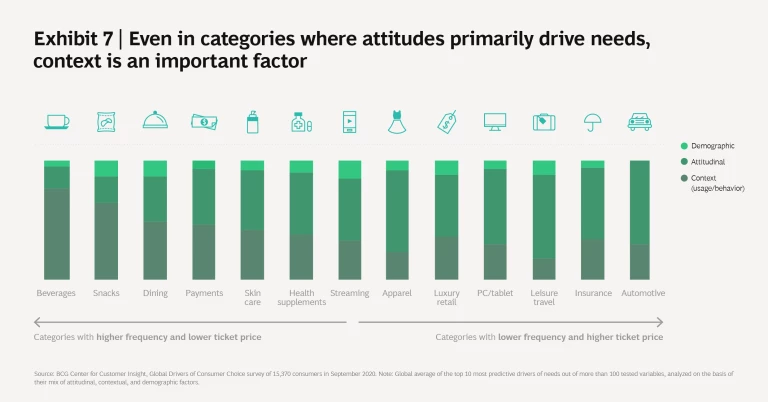

In fact, the more frequently consumers purchase or consume products within a category, the more context tends to matter. Even in big-ticket, low-frequency categories such as luxury goods, automobiles, and insurance, however, we found that two or three of the top ten drivers of needs are contextual. (See Exhibit 7.) Developments such as the COVID-19 pandemic and whether a policy is bundled with travel influence purchases of insurance, for example, while for PCs context such as whether the purchase is for a gift is important to understand a consumer’s needs at the time of purchase. Demographics mattered little in differentiating needs. Our findings indicate that age is the only demographic factor that significantly impacts purchasing and consumption decisions. In none of the 13 product and service categories did gender or income strongly define needs.

Context also plays an important role in categories that businesses have traditionally regarded as being highly associated with the consumer’s personality, such as automobiles. Our research found that attitudes such as the belief that the car “represents who one is” are important. But the two leading considerations that defined needs in consumers’ most recent purchase were contextual: whether they were buying their first vehicle and what specific use cases they had in mind for the car, such as whether it would be driven on highways or off road. In the case of health supplements, the location where the buyer planned to consume the product took precedence over such factors as attitude toward health and whether the consumer typically preferred natural products.

Context tends to have a greater impact on consumer needs than demographics, such as gender.

Context also tends to have a greater impact on consumer needs than demographics, such as gender. One might imagine that a Mars-versus-Venus divide exists in connection with restaurant dining needs, for example. But when we asked males and females globally to name the most important emotional needs they sought to satisfy on a dining occasion, they gave surprisingly similar responses. The biggest difference is driven by whether consumers are dining with others or alone.

As for the importance that consumers attach to price, we again detected the strong influence of context. We asked consumers about the last time they purchased a snack. Did they buy the lowest-price option, or one costing slightly (less than 5%) more, if available? We classified respondents who picked the lowest-price option despite the low difference in price as “price sensitive.” We found that more respondents globally picked the lowest-price snack when they were low on energy or were eating with children. Fewer consumers were price sensitive when buying a snack at a grocery store or consuming nothing else with it.

Likewise, more consumers were price conscious when dining out with children than when dining alone. And consumers tend to select higher-priced dining options on Saturdays than they do on Tuesdays. When it comes to cars, consumers pay closest attention to the sticker price when they are buying their first vehicle and when they use it frequently, such as for commuting to work or shuttling children to and from school. Price is less of an object if the car’s primary use is for leisure travel.

The impact of context variables themselves differs around the world and reflects nuances of particular markets. When we asked consumers with whom they had eaten their most recent purchased meal, for example, the most frequent response in Western nations was “spouse or partner,” ranging from 36% in Germany to 40% in the US. In Japan and China, however, consumers most frequently said that they had dined alone. Such significant differences mean that companies need to understand context and its influence locally.

Implications for Global Brands

The profound shifts in the global consumer market generated by the COVID-19 pandemic are creating enormous opportunities for companies with the best understanding of consumers’ needs and the factors that influence their decisions. Most companies have extensive experience in researching demographics, attitudes, and needs. But in our experience, they need better research that will enable them to analyze hundreds of variables to find the handful that really matter in consumers’ purchases and consumption in specific markets and circumstances.

Marketers need to better balance what people say they value with what consumers actually do in real purchase and consumption situations.

Marketers need to better balance consumer mindsets—what people say they value—with what consumers actually do in real purchase and consumption situations. Otherwise, they risk missing key tradeoffs that consumers make in the moment and, as a result, capturing only a fraction of the potential in their sector.

We believe that our findings have the following key implications for brands:

- Don’t bet the farm on consumer archetypes. Although marketers should continue to invest in understanding demographics and attitudes, building a global campaign around generic consumer archetypes would be unwise. Even if Gen Z consumers in different countries engage with the same social media channels, for example, they don’t necessarily share similar attitudes when it comes to deciding which products to buy. A company’s marketing campaign must take into account geographic differences in local mindsets. Certainly, companies should still reach out to consumers through social media. But they should tailor the messages to the local audience.

- Pursue nuanced global strategies, even in categories that aren’t traditionally localized. Because consumer needs vary around the world, the idea that a company can conquer a category with a one-size-fits-all strategy is a myth in most categories. Brands that adapt their value propositions to local needs—as Philips, Nestlé, Starbucks, and McDonald’s have done—tend to outperform in their categories. This holds true even in categories such as insurance payments, where global strategies are more common.

- Don’t pursue blanket loyalty by trying to be all things to your target consumers. It’s natural for companies to try to build brand loyalty and win as much of a share of the consumer’s wallet as they can. But there is no such thing as blanket customer loyalty. Even loyal consumers make different decisions under different circumstances. Rather than dilute brands, companies must invest in understanding and owning specific needs that occur at specific moments of purchase or consumption, particularly in categories that involve more frequently purchases and lower ticket prices. Similarly, pricing strategies that take into account when, where, and with whom products are purchased and consumed can capture value opportunities that the brand might otherwise miss.

Consumer marketing has made enormous strides as an art and a science in recent decades as companies develop sophisticated techniques to pinpoint target markets across the globe and delve ever deeper into the consumer’s psyche. Nevertheless, we believe that many companies are leaving significant value on the table that they could capture with a more comprehensive approach to understanding the key factors that uniquely predict purchases and consumption of a particular good or service in a particular market. As the global economy grows more complex, companies that can cut through the static and unlock the secrets of consumer choice, by market and by context, will be in the best position to differentiate and win the ever-intensifying scramble for competitive advantage.