As economies reopen following the damage wrought by COVID-19, businesses are rethinking their operations, seeking to transform themselves into more nimble and resilient organizations. This is, in fact, an historic opportunity for companies to “build back better.”

Leading organizations are focusing particularly closely on their global supply chains. They are striving to enhance their supply chains’ agility and efficiency. (BCG has written elsewhere about things companies should keep in mind as they do so, including how to make their supply chains more stable and prepare for subsequent disruptions .) Critically, these organizations are also working to improve their supply chains’ sustainability (as well as the sustainability of their supply chain partners), often experimenting with unprecedented types of collaborations with suppliers, customers, and even competitors across sectors and geographies. The companies have concluded that these extra efforts are a high-payback investment, since greener supply chains can deliver benefits for both business and the environment.

Here we present our broader argument for greener supply chains. We think you’ll find it compelling.

Spurred by rising pressure from investors, consumers, regulators, and other stakeholders, more and more companies in 2020 are scrutinizing the environmental effects of their businesses. In fact, in his January 2020 letter to CEOs, Larry Fink, chairman and CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, put companies on notice that investors, among other stakeholders, now expect full disclosure regarding companies’ performance on environmental, social, and governance factors.

As companies increasingly view their business strategies, investments, and business models through the lens of environmental impact, they would do well to focus on one specific element: their global supply chains. According to CDP, an international nonprofit that promotes environmental disclosure, the impact of end-to-end supply chains on emissions is more than five times that of companies’ direct operations. But greener supply chains—including direct operations—can also translate into sizable financial and commercial benefits for companies, especially over the longer term. In our detailed study of three diverse industries, we found that such benefits include lower operating costs, a stronger brand, continued social license to operate, and improved access to resources.

To understand the challenges and opportunities facing companies as they work to improve the environmental footprint of their supply chains, we analyzed 500 company examples across three industries—consumer packaged goods (CPG), metals, and chemicals. We also interviewed 50 operations and supply chain leaders.

The impact of end-to-end supply chains on emissions is more than five times that of companies’ direct operations.

A Look at Three Industries

Although the industries and business of CPG, metals, and chemicals are very different, they share three characteristics.

First, their operating practices and supply chains have sizable effects on the environment. If the CPG sector were a country, its carbon-dioxide emissions would be second only to those of China. The metals sector expels an estimated 300 million tons of toxic waste in rivers and streams each year. Fertilizers and other products produced by the chemicals sector are associated with a 30% reduction in biodiversity when found in the soil.

Second, progressive leaders in each sector are setting ambitious targets to improve their environmental performance. In CPG, for example, Unilever has committed to being “carbon-positive” by 2030 by eliminating fossil fuels from its operations and generating more renewable energy than it consumes. Danone aims to eliminate deforestation in its supply chain in 2020. In metals, aluminum producer Novelis is reducing water intensity in its operations by 27% in 2020. In chemicals, International Flavors & Fragrances aims to derive 75% of its energy from renewables, and to reduce its energy usage by 20%, by 2025. There are many other examples.

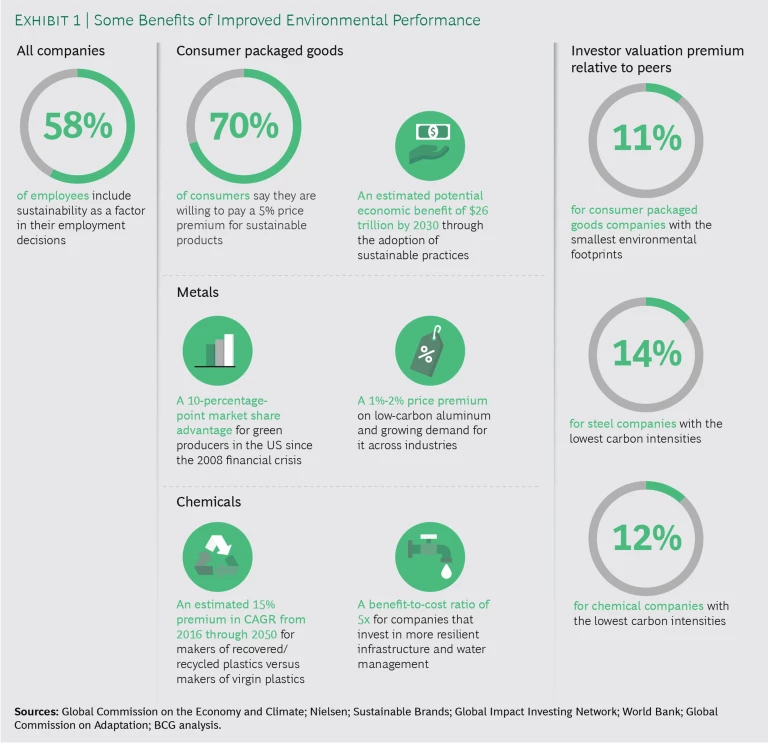

Third, by improving their environmental performance, these companies could not only improve the planet’s prospects but also significantly improve their business results through related cost reduction, revenue enhancement, greater innovation, access to new markets, brand enhancement (potentially supporting premium pricing), greater ease in attracting and retaining talent, and other benefits. (See Exhibit 1.)

Consumers support such efforts—70% say they are willing to pay a 5% price premium for products produced by more-sustainable means. Already such sustainable products are estimated to account for fully half of the CPG sector’s current growth. We estimate that early movers in the metals sector—that is, companies that proactively embrace more

sustainable operations

—could capture up to a 25% cost advantage over peers that take a wait-and-see approach (assuming the implementation of a carbon-pricing scheme).

Companies in all three sectors could also enhance their investment attractiveness and, in turn, total shareholder returns by embracing greener operations. According to our research , CPG businesses that are considered leaders in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria have an 11% valuation premium over their competitors. Similarly, we found that companies in the steel and chemicals sectors that outperformed their competitors in carbon emissions per dollar of revenue enjoyed valuation premiums of 14% and 12%, respectively.

CPG companies that are considered leaders in ESG criteria have an 11% valuation premium over their competitors.

Portfolio Approach to Environmental Performance

Companies can take action across the entire value chain, from design through end of life, to improve their environmental performance:

- Innovative Product Design and Packaging. These actions are aimed specifically at reducing the company’s environmental footprint, including the footprint of its supply chain.

- Enhanced Sustainability of Inputs and Suppliers. Examples include using raw materials that have a relatively favorable environmental footprint, powering the company’s operations with green energy sources, and favoring suppliers that emphasize renewables.

- Increased Efficiency in the Use of Operational Resources. For example, recycling and reusing water consumed in operations.

- Optimization of the Supply Chain Network. This reduces the negative environmental effects of the movement of materials and finished goods across the supply chain. An example is increased localized sourcing.

- Adoption of Circular-Economy Models . That means turning waste to value wherever possible. An example is using post-consumer recycled content to make new packaging.

Of course, companies will find themselves on a spectrum in each area. We therefore analyzed more than 200 levers to create a maturity curve for each area.

Table stakes moves are actions many companies have already taken; firms that have failed to do so will need to adopt these practices relatively soon to remain competitive and avoid triggering concerns among consumers, regulators, and investors. Examples of table stakes moves might be installing LED lighting, solarizing facilities, and diverting waste from the company’s direct operations away from landfills.

Incremental solutions address a particular challenge or issue that can be scaled more broadly across the organization—for example, process and design changes to maximize the recovery and reuse of byproducts. Most of these are still relatively uncommon and will demand some innovation and investment to bring them fully to scale.

Transformative actions create step changes in the environmental performance of the supply chain and differentiate the company from its competitors. Examples include fundamentally redesigning the supply chain network by decentralizing production using 3D printing or developing innovative business models that include both the public and private sectors. BCG has identified seven types of such transformative business models .

To substantially improve the environmental profile of their supply chains and operations, most companies will need to employ combinations of those three types of actions. That will require a “portfolio approach,” in which options are weighed and balanced regularly, and sequencing investments accordingly.

Substantially improving the environmental profile of supply chains will require regularly weighing and balancing options and sequencing investments accordingly.

Opportunities by Industry

Companies can take a range of win-win (meaning positive for both the environment and business) actions in the three industries we examined. Here we highlight examples, and we take a closer look at several transformative moves in each industry.

Consumer Packaged Goods

CPG companies have discovered ways to improve environmental performance while saving money on operations and generating commercial benefits. (See Exhibit 2.) Examples include the following:

Examples include the following:

Innovative Product Design and Packaging. Production of Beyond Meat’s meat replacement products uses 99% less water and 93% less land, and emits 90% less greenhouse gases, than the production of traditional meat-based products. The company created massive market value through its IPO and is experiencing booming product sales. Many companies are already rethinking their product portfolios in the wake of COVID-19; some consumer-goods companies, for example, are reducing their number of offerings to ease the scope of the demands on their supply chains. For such companies, now is an opportune time to also consider environmental impact.

Enhanced Sustainability of Inputs and Suppliers. Danone uses satellites and sophisticated sensors to track its suppliers’ soil health and improve growth in sustainable yields.

Increased Efficiency in the Use of Operational Resources. PepsiCo’s water conservation efforts in plants saved it more than $80 million from 2011 through 2015. Such efficiency-oriented moves, by reducing companies’ reliance on resources that could experience shocks due to climate change, environmental degradation, and other factors, can also help deliver the greater resiliency that companies are seeking post-COVID-19.

Optimization of the Supply Chain Network. Post is reducing its carbon footprint by increased localization of sourcing; wheat used in its Weetabix cereal, for example, is harvested less than 50 miles from the UK plant that manufactures it. We anticipate a major rethinking of supply chains by companies across CPG as they seek to optimize their operations for the days ahead; adding environmental criteria to the list of key considerations is something most, if not all, businesses should consider.

Adoption of Circular-Economy Models. Kellogg’s and Seven Bro7hers Brewery partnered to create a beer composed substantially of byproducts from the Kellogg’s production process.

Two transformative levers worth highlighting are engagement with suppliers to increase the sustainability of products; and the scaling of circular-economy products. The former requires suppliers to set aggressive targets for shrinking their environmental footprint and to share best practices in agriculture and forestry. Done successfully, these efforts can result in reduced greenhouse-gas emissions, waste production, and water usage, and greater conservation of biodiversity. They can also increase revenues, lower costs, enhance brands, and give companies a renewed social license to operate.

Multiple CPG companies are exploiting this lever. L’Oréal, for example, chooses more than 80% of its strategic suppliers based on their environmental and social performance. In Pakistan, PepsiCo trained more than 600 farmers in sustainable farming practices and reduced water usage by 30% while lowering PepsiCo’s business costs; the farmers’ incomes also increased 30%.

By promoting reuse and recycling, the scaling of circular economy products can substantially reduce the need for primary and secondary packaging.

The scaling of circular-economy products is less mature but offers a significant upside in CPG. Its primary environmental benefit is waste reduction; by promoting reuse and recycling, it can substantially reduce the need for primary and secondary packaging. In parallel, it can lead to a number of significant business benefits for practicing companies, including higher revenues through price premiums and access to new customer segments; brand enhancement due to high visibility among customers through repeat transactions; and a strengthened social license to operate, as well as the potential to reduce a company’s vulnerability to regulatory risk (including the risk of a ban on single-use plastic containers).

A company on the cutting edge of this evolution is The Loop Store, launched by Tom Szaky, founder of recycling firm TerraCycle. The company delivers a range of name-brand products, from liquid detergent to orange juice, in multiuse metal and glass containers directly to consumers; picks the containers up (or accepts delivery from customers) after they have been used; cleans the containers; and repeats the cycle on an ongoing basis. Businesses that have bought into The Loop Store’s model and partnered with the company to distribute their products include Nestlé, Clorox, Danone, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and others.

Other CPG companies leading the charge on this front are Nestlé and Mars. The companies, working alongside energy company Total and plastic recycling technology provider Recycling Technologies, are seeking to advance chemical recycling in France, with an aim of enabling the recycling of complex plastics used in food packaging that are currently considered non-recyclable.

Metals

Metals companies also have a range of levers at their disposal for improving their supply chains’ environmental performance. (See Exhibit 3.) Examples include the following:

Examples include the following:

Innovative Product Design and Packaging. Alcoa and the auto industry are engaged in the co-design of a lightweight metal aimed at reducing vehicle emissions. Demand for the alloy is expected to be more than ten-times higher than its current level by 2025.

Enhanced Sustainability of Inputs and Suppliers. Fully 95% of the energy RUSAL employs comes from non-carbon sources. This gives the company a leg up in retaining customers seeking green producers.

Increased Efficiency in the Use of Operational Resources. Alcoa and Rio Tinto, in partnership with the Canadian government and Apple, established ELYSIS, a joint venture aimed at developing carbon-free aluminum. With a combined investment of nearly $100 million, the two companies are expecting a 15% savings in operating expenses and a similar gain in productivity.

Optimization of the Supply Chain Network. A global steel company used advanced analytics to optimize logistics and minimize shipping, saving $30 million. In the wake of COVID-19, we expect growing numbers of metals companies to optimize with an eye toward greater resiliency, in particular, to ensure their ability to serve customers consistently.

Adoption of Circular-Economy Models. AK Steel uses recycled concrete and pavement debris in metals production, saving the company more than $600,000 a year.

Transformative moves include the introduction of advanced analytics to enable more robust planning; and the optimization of plants with machine learning.

More robust planning and scheduling can translate into substantially improved productivity and hence a greatly reduced environmental footprint, with greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, waste production, and resource usage all reduced materially. The possible business benefits include lower costs, potentially greater innovation by further applying advanced analytics to operations, and a strengthened social license to operate resulting from the more efficient use of resources.

More robust planning and scheduling can translate into substantially improved productivity and hence a greatly diminished environmental footprint.

One steel producer used advanced analytics to boost its productivity by 1%. While this sounds relatively modest, the gain translated into approximately $67 million in greater production—or four days’ worth of output at no additional capital cost—and 80,000 fewer tons of carbon dioxide emissions per year. The company also saw its energy costs fall and bottlenecks in its supply chain decrease.

Advanced analytics is also used to optimize the efficiency of company-owned plants with machine learning. But here the aim is to look directly for improvement opportunities along the length of the supply chain. One steel company we worked with applied this lever to improve demand planning and forecasting; the effort reduced oversourcing and supplier overproduction and rationalized the movement of goods along the supply chain. That saved approximately $11 million to $17 million in costs annually and reduced annual carbon dioxide emissions by 20,000 tons.

In our observation, companies that had instituted control towers and other digital solutions before COVID-19 were better able to navigate the crisis than those that had not. The companies had better tools, data, and visibility into their supply chains, allowing them to identify and move early on both problems and opportunities.

Chemicals

As with CPG and metals, chemical companies can deploy a range of levers to boost the environmental profile of their supply chains and enhance business performance. (See Exhibit 4.)

Examples include the following:

Innovative Product Design and Packaging. Novamont generates approximately $170 million annually through the sale of biodegradable and compostable products.

Enhanced Sustainability of Inputs and Suppliers. Solvay’s biomass-powered boiler improved the company’s productivity and has reduced its emissions 30%.

Increased Efficiency in the Use of Operational Resources. International Flavors & Fragrances developed a process to transform byproducts into new raw materials for fragrances.

Optimization of the Supply Chain Network. CF Industries located its facilities closer to crop-growing regions to improve the company’s environmental profile. Such moves, aimed at shortening the length of the supply chain, stand to deliver sizable value in the post-COVID era, given the growing premiums companies attach to timely delivery and high standards of service.

Adoption of Circular-Economy Models. Dow Chemical has co-designed packaging that reduces plastic usage by more than 80% and consumer costs more than tenfold.

Transformative moves include leveraging industrial symbiosis and installing carbon-capture technologies. Industrial symbiosis refers to collaboration among companies aimed at reducing waste and lowering the cost and volume of production inputs by creating a closed loop in which one company’s waste is another’s raw material. This can deliver a wide range of environmental benefits, including substantially reduced greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, and waste production. Moreover, lower costs for inputs and waste disposal reduce business costs; enhance revenue through the sale of waste to other parties as raw material; strengthen social license to operate through the company’s greener environmental profile and potentially favorable impact on local job creation; and enhance innovation, since making such an arrangement work requires fresh thinking and ways of working, which can help create a more idea-generating culture.

A paradigm of industrial symbiosis is Denmark’s Kalundborg Eco-Industrial Park, a closed-loop ecosystem of industrial companies that has expanded organically over 50 years. Kalundborg thrives on its strategic management of energy, water, and waste, with one company’s waste serving as another’s raw material. The vast environmental benefits of this arrangement include estimated reductions of 275,000 tons in carbon-dioxide emissions and 3 million cubic meters of water usage, compared with usage levels if the companies were operating in isolation. The business benefits to participating companies are also significant. Novo Nordisk, the world’s largest producer of insulin, for example, saves substantially on its production costs by sourcing cheap steam from fellow participant Ørsted, for which steam is a waste product. Simultaneously, Novo Nordisk reduces its disposal costs by transferring its ethanol waste to a nearby biogas reactor.

Carbon-capture technologies are another example of a potentially transformative lever. These have the potential to eliminate as much as 80% of the chemical industry’s greenhouse gas emissions; successful adoption will demand balanced investment and a strategic transition. But the potential peripheral benefits include increased demand for sustainably developed products and for captured carbon; and a stronger brand and social license to operate due to visible commitment to more-sustainable operations. Companies will presumably continue to attach high priority to these outcomes, and hence invest in these technologies, in the post-COVID world.

Carbon capture technologies have the potential to eliminate as much as 80% of the chemical industry’s greenhouse gas emissions.

How to Get Started

We believe that every supply chain needs a sustainability strategy. To develop an effective one, we suggest the following:

- Confirm where the company’s supply chain stands today with regard to its environmental impact. Identify improvement initiatives (and their owners) that are already under way in your supply chain, and determine the speed of progress of those initiatives. Benchmark your company’s initiatives against those of other companies in your industry.

- Build a supply chain materiality matrix that identifies the most critical environmental issues your supply chain faces today and will likely face tomorrow. Define your ambition, along with relevant metrics, for each high-priority topic.

- Identify the potential levers, such as the sector-specific moves we’ve outlined, that can address your most critical environmental issues while simultaneously delivering business benefits. Take a portfolio approach, implementing table stakes moves to remain competitive against peers in most areas while prioritizing the company’s most material issues.

- Design an environmental performance strategy and transformation plan. Rank actions according to potential impact and implementation complexity to identify quick wins. Leverage organizational knowledge and external partnerships.

To support the strategy you’ve developed, consider the following actions:

- Convey to stakeholders that there is buy-in to the sustainability initiative from the CEO and the leadership of external supply chain partners. As the COO of one global food company said, “For us, owner and shareholder buy-in, and CEO commitment, are the drivers of action.”

- Offer a clear vision and cohesive narrative regarding how environmental sustainability is built into the supply chain.

- Build a rigorous business case that prices in intangible and strategic benefits as well as environmental impact. Said the vice president of sustainability at a global chemicals company, “All our investment decisions are assessed through a triple-bottom-line framework that evaluates sustainability and financial metrics.”

- Partner with governments and other stakeholders to drive the development of critical infrastructure and ambitious regulation to level the playing field among companies.

- Set goals and establish measurement practices to track results and ensure accountability among relevant parties.

- Engage stakeholders across the supply chain, including suppliers, internal employees driving change, and consumers. “Partnerships between competitors, customers, and the public sector are a key element to accelerating adoption of carbon-neutral technologies,” said the vice president of sustainability at a global metals company.

- Demonstrate proactively to investors how sustainability is embedded into the supply chain and delivering both environmental benefits and business benefits to the company.

- Institute strong governance and the right organizational structure, one that reinforces ownership and responsibilities.

- Build supply chain teams that have well-defined accountabilities and incentives. “We introduced variable compensation linked to direct emissions,” said the vice president of sustainability at a global metals company. “The KPIs cascade down to the operator level.”

- View decision points on the path to boosting the post-COVID-19 readiness of the company’s supply chain as opportunities to concurrently strengthen the supply chain’s environmental profile. As noted, there are potential synergies between the two, meaning the steps taken to meet one can help meet the other.

A Win-Win-Win

Implementing a clearly defined, well-managed strategy for supply chain environmental performance can deliver measurable environmental benefits that the company and its stakeholders will welcome. It can also bring substantial business benefits, including better positioning of the company for tomorrow’s world of higher disclosure and investor scrutiny, more environmentally focused consumers, and scarcer resources. And, critically, it can contribute substantially toward the pressing objective of building the resiliency necessary for success in a post-coronavirus landscape.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleagues Cornelius Pieper, Matthias Bäumler, Shalini Unnikrishnan, Francesco Schettino, Gregor Schueler, and Ashley Cukier, and BCG alumna Supriya Thumpasery, for their contributions to this report.