Only one of Coca-Cola’s last six CEOs grew up in the United States. Deutsche Telekom set out to increase the representation of women in its management ranks in 2010, and now 40% of the people on its supervisory board are female. The Japanese beverage company Suntory didn’t promote an insider when it was looking for a new president to oversee a geographic expansion effort; it recruited the former chairman of Lawson, Japan’s second-largest convenience store chain. When companies undertake efforts to make their management teams more diverse by adding women and people from other countries, industries, and companies, does it pay off? In the critical area of innovation, the answer seems to be yes. A study of 171 German, Swiss, and Austrian companies shows a clear relationship between the diversity of companies’ management teams and the revenues they get from innovative products and services. (See “Study Methodology.”)

Study Methodology

BCG and the Technical University of Munich surveyed diversity managers, HR executives, and managing directors at 171 German, Swiss, and Austrian companies. The survey was conducted during the second half of 2016. Among the companies that took the survey, one-third had fewer than 1,000 employees, one-quarter had more than 10,000, and 42% had from 1,000 to 10,000.

The companies represented a wide variety of industries, including chemicals, technology, consumer goods, finance, and health care.

The links between diversity and innovation levels were calculated as Pearson’s r correlation coefficients, which use a range of +1 for completely positive correlations to –1 for completely negative correlations. (A correlation of zero means that there is no relationship at all between two variables.)

For certain parts of our analysis, we provided the coefficient of determination, R2, which describes the extent to which changes in one variable (in this case, innovation revenue) can be explained by another variable (in this case, a particular type of management diversity). R2 is the square of the correlation coefficient, r, and can range from 0 (0%) to 1 (100%).

We also examined relationships for statistical significance—the likelihood of results being repeated in other large data sets. In this report, correlations with p values of <0.01, <0.05, and <0.1 have “very high,” “high,” and “low” degrees of statistical significance.

The study comes at a time when diversity’s business benefits have become a topic of intense discussion. In the past, the indirect benefits of diversity were sufficient—an expansion of the job candidate pool at all levels, or an increase in social and political status for the company. Direct financial benefits weren’t needed to justify diversity initiatives—no one could even say for sure if such benefits existed. This study shows that they do.

BCG and the Technical University of Munich conducted an empirical analysis to understand the relationship between diversity in management (defined as all levels of management, not just executive management) and innovation. (See “How Diversity and Innovation Are Defined in This Report.”) Although the research is concentrated in a particular geographic region, we believe that its insights apply globally. The following are the major findings:

- The positive relationship between management diversity and innovation is statistically significant, meaning that companies with higher levels of diversity get more revenue from new products and services.

- The innovation boost isn’t limited to a single type of diversity. The presence of managers who are female or from other countries, industries, or companies can cause an increase in innovation.

- Management diversity seems to have a particularly positive effect on innovation at complex companies—those that have multiple product lines or that operate in multiple industry segments. Diversity’s impact also increases with company size.

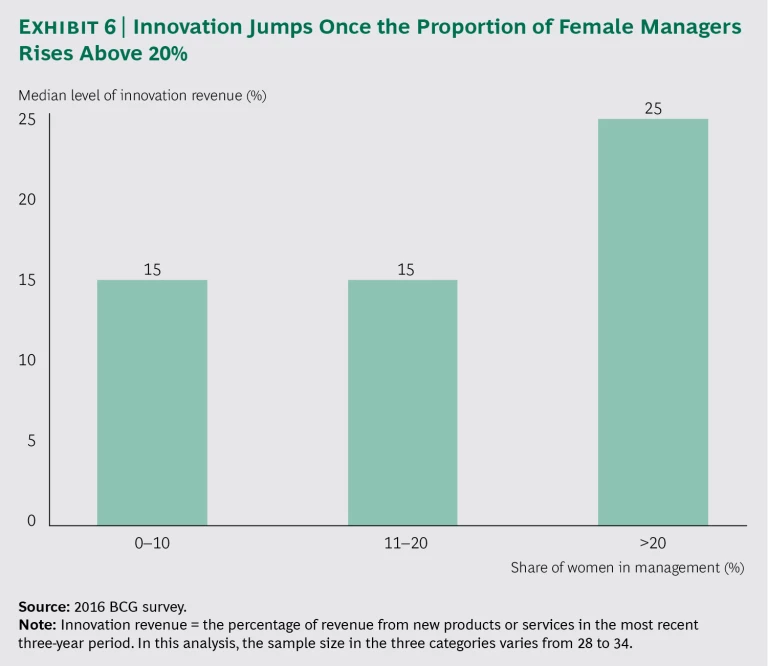

- To reach its potential, gender diversity needs to go beyond tokenism. In our study, innovation performance only increased significantly when the workforce included a nontrivial percentage of women (more than 20%) in management positions. Having a high percentage of female employees doesn’t do anything for innovation, the study shows, if only a small number of women are managers.

- At companies with diverse management teams, openness to contributions from lower-level workers and an environment in which employees feel free to speak their minds are crucial in fostering innovation.

How Diversity and Innovation Are Defined in This Report

The BCG-Technical University of Munich study looked in detail at six types of diversity:

- Gender: the percentage of women who are in management at any level (not just executive management)

- Country of origin: the percentage of managers who are born in other countries or who are the children of parents born in other countries

- Career path: the percentage of managers who have worked at other companies

- Industry: the percentage of managers who have experience in sectors other than the surveyed company’s

- Age: the extent to which managers are evenly distributed across age groups; this is calculated using the Blau index, which pinpoints the amount of heterogeneity in a sample

- Academic background: the differences in university degrees and other aspects of academic training among members of management; calculated using the Blau index

“Innovation revenue” in this report refers to the share of revenues that companies have generated from enhanced or entirely new products or services in the most recent three-year period. For the companies in our study, 26% is the average amount of innovation revenue.

Diversity’s Positive Link to Innovation

That management diversity might be linked to innovation isn’t a new concept. It’s rooted in the assumption that diversity leads to different perspectives and novel solutions. This is, however, a difficult thing to prove. Unlike other innovation catalysts—R&D spending, for instance, or a specific strategy emphasizing innovation—diversity has an indirect connection to innovation. Until now, most of the research about it has been more qualitative than quantitative.

The BCG-Technical University of Munich study used statistical methods—correlations and regression analyses—not only to show that a relationship exists between diversity and innovation but also to identify the types of companies that get the biggest innovation boost from diversity, the steps that companies can take to increase diversity’s power, and the types of diversity that matter the most. This last area of inquiry is particularly important because many companies’ diversity strategies are no longer focused solely on traditional forms of diversity, such as gender and nationality. Instead, they have expanded, under the catchphrase “2D diversity,” to incorporate so-called acquired diversity, which includes people with cross-industry expertise and nonlinear career paths.

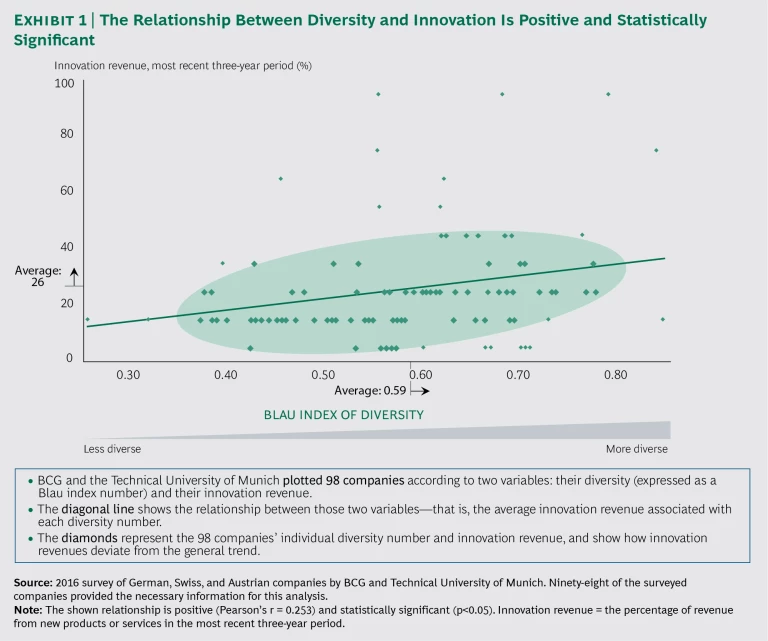

The companies were first analyzed using the Blau index to aggregate their levels of diversity in six areas. (See the Appendix for an explanation of the statistical analysis and terms used in this report.) The resulting diversity score was plotted against each company’s innovation level. We found that innovation revenue—which we define as the share of revenues from new products and services in the most recent three-year period—rises with diversity. (See Exhibit 1.)

Diversity and innovation don’t affect each other directly, the way sales of umbrellas by a street vendor rise on a rainy day; the relationship is more complex. Moreover, there are quite a few factors beyond diversity that can affect a company’s ability to innovate—such as the creativity of its R&D department, the executive team’s attitude toward taking risks, and shareholders’ support of new ventures. Still, management diversity influences innovation on its own. Diversity and innovation move together, and the relationship is statistically significant—meaning that there is a high probability of its repeating in any large population of companies.

An initial sense of diversity’s impact on innovation can be derived by comparing companies that are more diverse with those that are less diverse. In our study, companies with Blau index scores above 0.59 (above the median) have generated 38% more of their revenues, on average, from innovative products and services in the most recent three-year period than did companies below the median.

The study’s numbers become even more instructive when they are broken down along other dimensions. This more nuanced analysis yields insights about how to get the most out of diversity and which types of diversity offer the biggest advantage.

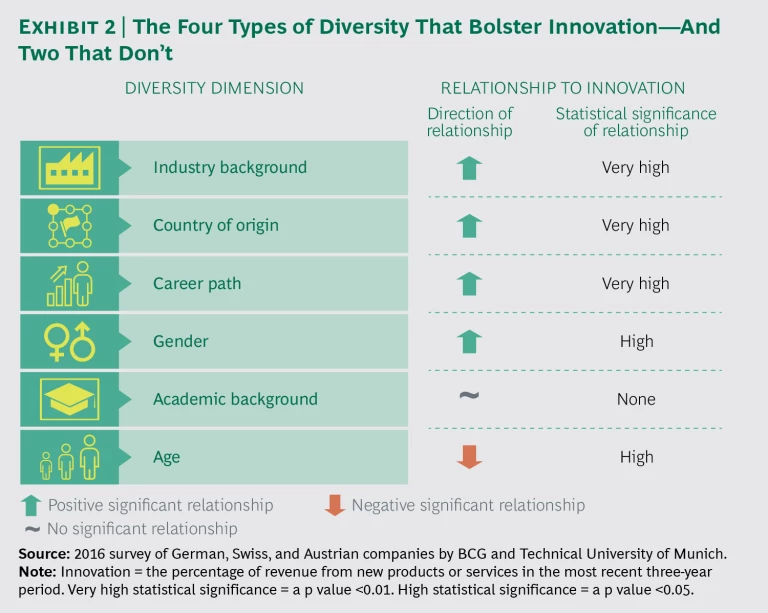

Of the six types of diversity analyzed in the study, four positively correlate with innovation: industry background, country of origin, career path, and gender. Age diversity (the extent to which managers are evenly distributed across age groups) is actually associated with less innovation. A sixth type of diversity, academic background, appears to have no impact at all on innovation, either positive or negative. (See Exhibit 2.)

Complex Companies and Large Companies Benefit the Most

Diversity has an especially positive impact on complex companies. And in many ways today, complexity is less a choice than a necessity: companies face so many risks that they can’t afford to be tied to just a single source of revenue. They also can’t afford to establish a management team whose members all have the same background (even if the team’s pedigree and skills are world-class) because that is less than optimal in terms of decision making. In short, the perfect management mix to enable innovation may not be the same at every complex company, but there does need to be a mix.

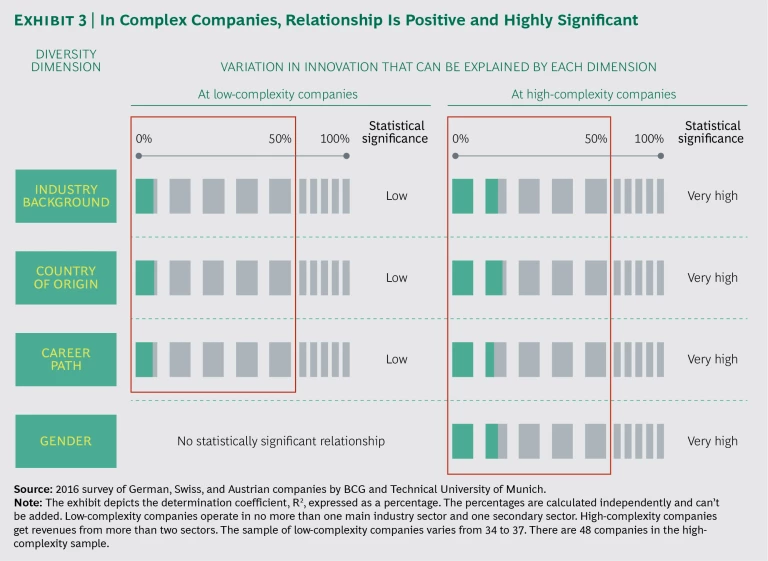

In complex companies, a significant positive relationship exists between innovation and industry background, country of origin, career path, and gender. The magnitude of the relationship is similar across these four dimensions, accounting for up to 18% of the variation in innovation. In companies with less complexity, the relationship exists only for the first three dimensions—and never explains more than 9% of the variation in innovation. (See Exhibit 3.)

Successful complex companies seem to recognize the value of diversity in their management ranks. Consider the German conglomerate Siemens, for example. The company has more than 350,000 employees, operations on every continent, and nine divisions in areas including power and gas, renewable energy, and building technologies. Roughly a decade ago, Siemens set an objective to become significantly more diverse at the management level. The company has made considerable progress toward that goal. Its 20-person supervisory board now includes 13 people who don’t currently work at Siemens or who came to it after starting their careers elsewhere, people with at least ten different educational backgrounds, six women, and four people born outside of Germany. Siemens’ supervisory board also reflects a range of ages, with the youngest board member being 44 and the oldest 74.

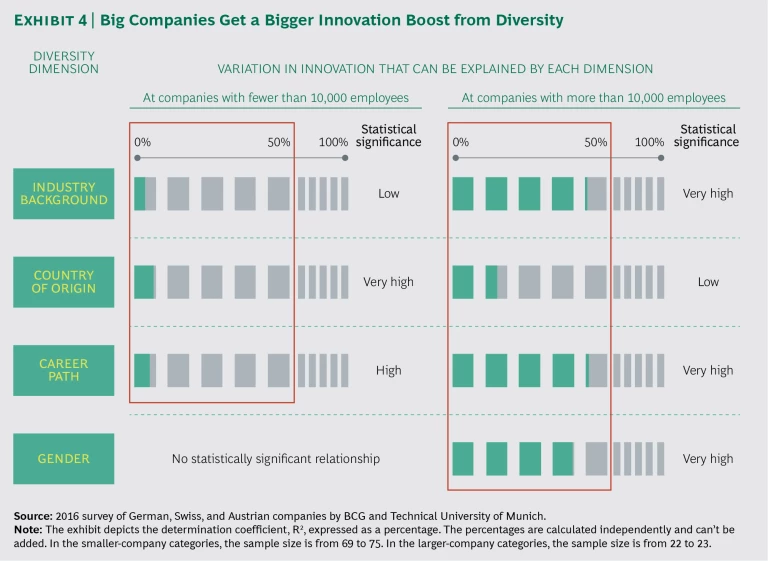

In addition to complexity, organizational size is relevant to understanding the impact of management diversity. There’s a sort of slipstream effect at big companies (probably because of the resources that they can marshal to make diversity pay off for them) in areas including innovation. In companies with more than 10,000 employees, management diversity accounts for a larger amount of the variation in their ability to innovate than at companies with fewer than 10,000 employees. For instance, up to 41% of big companies’ variation in innovation can be explained by diversity in the industry backgrounds, career paths, and gender of their managers. (See Exhibit 4.)

The Hot Button of Gender Diversity

Gender is the area of diversity that has undoubtedly received the greatest attention in recent years. For example, some countries now mandate a minimum representation of women on corporate boards, including Iceland and France (40%), Norway (at least 40%, depending on the size of the board), Italy (33%), and Germany (30%). These regulations weren’t written with the express purpose of increasing innovation—their agendas are broader. But even if increasing innovation had been their sole purpose, the laws would still have made sense. (See “The Impact of Women’s Participation on National Innovation.”)

The Impact of Women’s Participation on National Innovation

Every year, Cornell University, INSEAD, and the World Intellectual Property Organization (the entity that awards patents) rank countries by how innovative they are. We looked at the 2015 ranking in relation to women’s labor force participation to get a sense of how women’s participation can affect innovation.

It turns out that some of the most innovative countries also have extremely high levels of female labor force participation. This includes Switzerland (76% female workforce participation rate, first among all countries in the 2015 Global Innovation Index), Sweden (74%, third), and Iceland (82%, thirteenth).

In light of the positive effect that women’s participation has on national innovation, countries may want to know how they can get a higher percentage of women into the workforce. The political framework of a country (including tax policy and laws relating to antidiscrimination and pay equality) can have a big impact on women’s willingness to work, our study shows. So can structural factors, such as the availability of childcare, and societal values, such as support for women who are career-oriented.

Less important are marketing-oriented initiatives, including attempts to celebrate individual companies’ diversity initiatives at the national level. While they may shine a light on the practices of leading companies, in most countries such awards don’t seem to have any real bearing on women’s workforce participation or on other substantive issues, such as women’s ability to receive fair pay or to advance into management.

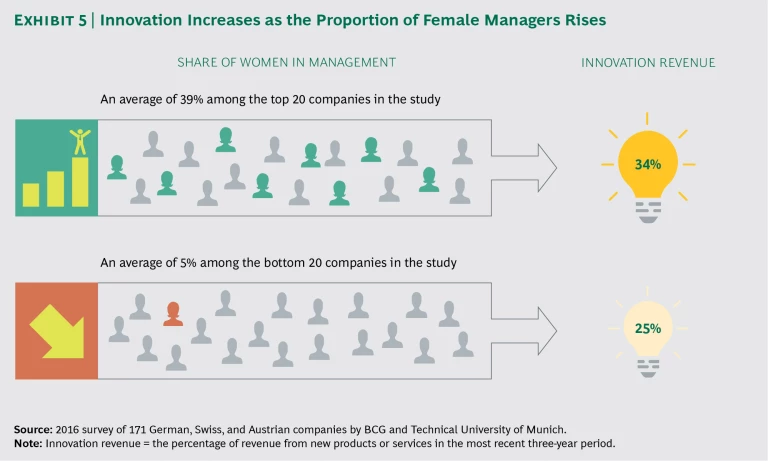

The study shows that companies with the greatest gender diversity (8 out of every 20 managers were female) generated about 34% of their revenues from innovative products and services in the most recent three-year period. (See Exhibit 5.) That compares with innovation revenues of 25% for companies that have the least gender diversity (only 1 in 20 managers were female).

The evidence also suggests that having a high percentage of female managers is positively correlated with disruptive innovation, in which a new product, service, or business model fully replaces the version that existed before (such as what Netflix has done to DVD rental stores and what Amazon is doing to retail.)

One thing that doesn’t seem to have an effect on innovation is the overall percentage of women in a company’s workforce. Only when women occupy a significant share of management positions does the innovation premium become evident: innovation revenues start to kick in when more than 20% of managers at a company are female, our survey shows. (See Exhibit 6.) Below that threshold, organizations remain male dominated, and it’s harder to capture the innovation potential of gender diversity.

The survey also highlights at least one sizable gap in companies’ efforts to put women in management positions and keep them there. The gap has to do with senior leaders’ commitment to gender diversity. The importance of this is obvious: even small gestures from senior leaders can have considerable influence. “You are very dependent on leaders’ behavior; you have leaders who pay attention to inclusion and leaders who don’t,” a top HR executive who participated in the survey said in a follow-up interview. While approximately two-thirds of all companies say that visible commitment on the part of senior leaders is most effective in promoting gender diversity at a management level, only half say such commitment is evident at their companies. What’s more, initiatives for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) workers mostly remain on the horizon. (See “LGBT: Just Starting to Appear on the Radar.”)

LGBT: Just Starting to Appear on the Radar

Most of our survey respondents (79%) said that they don’t know the sexual orientation of the people who hold management positions at their companies. Most also don’t have any initiatives in place to help lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender workers attain such positions.

Those that do have such initiatives, however, have typically adapted policies that existed for other minorities to include LGBT workers. Such companies also tend to have a higher focus on innovation. (Innovation focus is derived from respondents’ answers to a set of qualitative questions; it is different from innovation revenue, which is a quantitative measure.) This may be because these companies are more open to new ideas and ways of thinking, and have a generally more expansive world view.

Another area in which companies still have some work to do is diversity with regard to age. The results of the survey—in which greater age diversity was linked to lower innovation—suggest that companies haven’t learned how to leverage different levels of seniority on their staffs. Some companies are making strides, however. The German software company SAP has put “cross-generational intelligence” on its diversity and inclusion agenda, recognizing that, for the first time in its history, the company has members of five generations working together and that they have different expectations for how they want to be led, how they want to work, the kinds of flexibility that are important to them, and what constitutes satisfactory compensation. The company is trying to accommodate these different needs in order to ensure that intergenerational collaboration works and accrues to SAP’s benefit.

In addition to encouraging top managers to be more inclusive, companies can also use cultural and structural changes to attract and retain a diverse workforce. A number of the companies in our study already experiment with such changes. For instance, IXDS, a German design and innovation agency, has used part-time (80%) work contracts since its formation in 2006. The nontraditional schedule makes IXDS attractive to an inherently more diverse group of professionals, such as those who have interests outside of their day job (including research, teaching, and startup work). At the same time, it positions IXDS as an employer that accommodates employees during many phases of their lives. The resulting diverse workforce has a creative strength that IXDS’s clients appreciate when they are trying to solve digital and organizational transformation challenges.

Five Work Environment Factors That Amplify Diversity’s Impact

Our study provides clear evidence that having a diverse management team is a valuable asset when it comes to innovation. But as with any valuable asset, it needs to be developed to reach its potential.

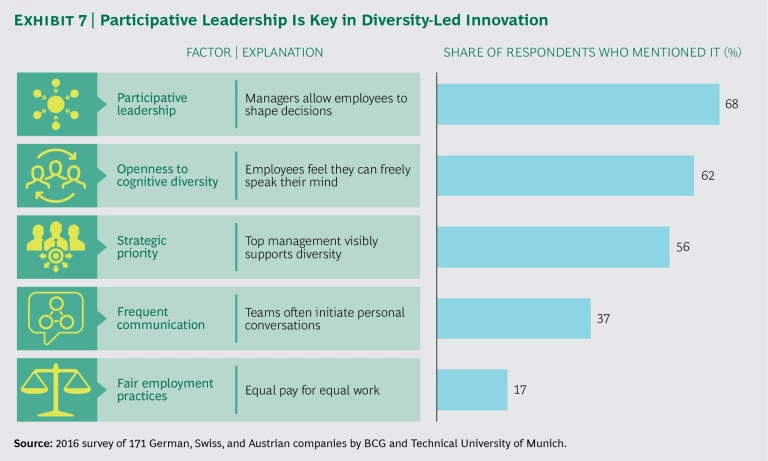

Diversity has the greatest impact on innovation at companies that reinforce diversity through five conditions in the work environment:

- Participative Leadership Behavior. When managers genuinely listen to employees’ suggestions and make use of them, diversity’s benefits multiply. Swarovski, the Austrian manufacturer of cut crystal, uses what it calls nudges to remind executives that their meetings will be more productive if attendees actively participate instead of deferring to those who are more senior. The nudges take different forms, including posters in hallways and whiteboard reminders in conference rooms.

- Openness to Cognitive Diversity. This describes a dynamic in which employees feel free to speak their minds. The German cable company Unitymedia, which participated in our survey, supports openness to cognitive diversity by encouraging opposing ideas and “constructive conflict,” in discussions both among peers and between employees and managers. A culture where change starts with a question, not a decision, “allows us to capture the potential of diversity,” an HR executive at Unitymedia told us in a follow-up interview.

- Strategic Priority. At some companies, diversity has considerable top management support. An example is France’s Airbus Group, whose Balance for Business initiative (aimed at increasing gender diversity at the largely male aeronautics company) has been endorsed by the top executive team, including the company’s CEO.

- Frequent Interpersonal Communication. When companies find ways to facilitate dialogue between people with different backgrounds, it can provide a creative spark and bolster innovation. Google does this through its cafés, which allow for spontaneous conversations among people who may have different educational, work, and national backgrounds, as well as vastly different levels of expertise.

- Equal Employment Practices. There’s nothing new or complicated about this concept, but it is still not universally implemented. Some companies are further ahead than others, however. The US apparel company Gap, for example, has won praise for eliminating the pay differences between its female and male employees. The apparel company’s commitment to gender diversity is also evident in the number of women on its senior leadership team and in the fact that a majority of its store managers are female.

For many companies, a crucial tactical question—over and above the impact of work environment conditions as a whole—arises from the amount of influence on innovation that each individual condition exerts. Of the five work environment conditions, participative leadership behavior appears to be the most important. Sixty-eight percent of companies said that it is a prerequisite to diversity-led innovation. The next most common prerequisite to innovation is openness to cognitive diversity, cited by 62% of companies. (See Exhibit 7.) The importance of these two conditions suggests that companies will have to look beyond formal initiatives and embrace “softer” tactics if they want to reap diversity’s innovation benefit.

On average, companies that ensure the existence of favorable work environment conditions generate 33% of their revenues from innovative products and services; companies that don’t get less than a quarter (24%). There seem to be other benefits, too: companies that create favorable work environment conditions have margins for earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) of 17% and revenue growth of 3.9%; those that don’t have 13% EBIT margins and 3.4% revenue growth.

Supportive work environment conditions are particularly helpful in amplifying the innovation impact of three types of diversity: industry background, country of origin, and career path. With strong support, diversity in these three areas has a positive impact on innovation. But when work environment conditions are weak, diversity in these areas does not lead to more innovation.

Creating More Diversity-Led Innovation: A Five-Step Process

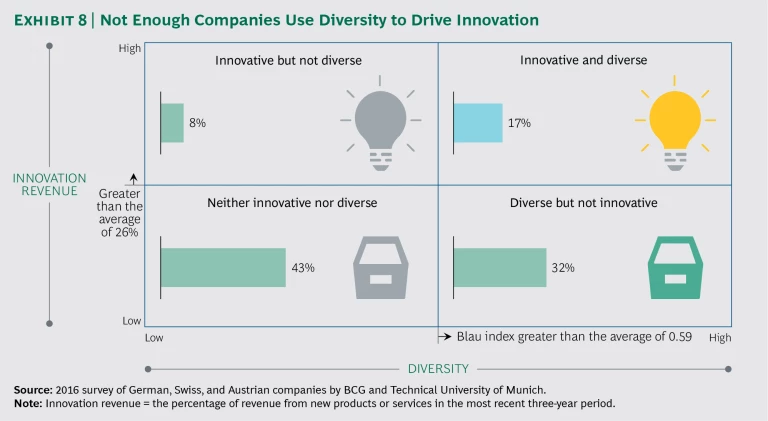

Our analysis shows that only 17% of all companies are above average in both diversity and innovation. Moreover, approximately one-third of companies are above average in diversity but lag in innovation. (See Exhibit 8.) Clearly, there is room for improvement.

In order to get more diversity-led innovation, companies should follow a five-step process.

Step 1: Analyze the status quo. The goal of this initial step is to understand the status quo for all three dimensions: innovation, diversity, and enabling conditions. For instance, a company might come out of Step 1 realizing it has below-average innovation revenues compared with others in its industry, diversity levels that are slightly above average overall but below the average in gender diversity, and weak work environment enablers, including management behavior that’s not particularly participative and ineffective communication mechanisms. Being clear about these starting points is an important part of developing a sustainable target state and roadmap for implementation.

Innovation is the first variable to consider, especially with regard to the company’s performance as an innovator (as reflected in revenues from new products and services) and to anything that may be hindering that performance. Through this analysis, companies may find that they have innovation-related deficiencies—such as product designs that appeal to too small a segment of the market or products that fail altogether—at rates that are well in excess of the industry average. Diversity comes next, as the company tries to pinpoint the amount and type of management diversity in its departments. One department that is especially important to look at is R&D, because of the role it plays in innovation and the contributions that diverse viewpoints can bring to the development of new products and services. (Too little management diversity in R&D can lead to blind spots in the product portfolio.) Finally, the company needs to look at its work environment conditions. In doing so, a company might come to understand, for instance, that it is too hierarchical, not inclusive enough in its decision-making processes, or is inadvertently sending the message that only certain people’s opinions count.

Step 2: Define the target. This is the most important step. A company must look at what’s happening in the market and with competitors in order to get a sense of whether it is behind, ahead, or at parity in innovation.

This outward-facing analysis (along with the company’s own sense of which areas of its business best lend themselves to innovation) can help the company identify the organizational changes it should make, the partnerships it should pursue, and the incentive programs it should put in place. The assessment could also help the company figure out where it could benefit from a more diverse set of managers. For example, a company might decide it needs more women running market research, more cross-industry managers overseeing commercial development, and more outsiders supervising manufacturing and production. That, in turn, could help the company determine which aspects of its work environment need to change—from the flexibility of working hours to managers’ listening skills.

IT tools could help with these efforts by reinforcing the ability of leaders to participate in making decisions, facilitating employee-to-employee communications, or supporting other key work environment conditions. (Google, for instance, uses a homegrown “moderator” tool in company-wide meetings to determine which questions to address on the basis of employee “votes.”) It’s in this step that the benefits of new IT tools should be identified and their functionality determined.

Finally, the new targets need to be reinforced by key performance indicators (KPIs). For a company looking to increase its level of innovation, a KPI might be doubling the percentage of customers who upgrade to follow-on products. There could be diversity KPIs too, such as being in the top quartile for fair employment practices, in order to attract and retain top talent.

Step 3: Identify the gaps. In this step, a company needs to identify what is missing to proceed from its current state to a target state of innovation, diversity, and enablers.

Comparing the status quo with the target can help. For example, if a company has a greater-than-average number of patent grants but still lags in innovation revenue, its commercialization skills could be deficient. Or a company that is losing ground in a fast-growing foreign market might conclude that it doesn’t have enough local managers in place.

In most cases, there won’t be just a gap or two—there will be dozens or hundreds. The trick is figuring out which ones are the most important and prioritizing them.

Step 4: Create a roadmap for action. Here, the company makes a plan for closing the gaps on the basis of the priorities it has identified. The plan will inevitably be complex, with multiple parts, interdependent milestones, and clear timelines. The quality of the implementation is key. Pilot programs can be very helpful, especially in areas where the plan is likely to encounter resistance. These pilots give the organization a chance to learn and to find its footing in a context that offers low risk and high return.

Step 5: Institutionalize the process. An important opportunity is lost when companies treat the steps as a one-off activity. A far bigger innovation benefit will result if the process is ongoing and becomes a permanent part of company operations, with target- and goal-setting evolving in response to new tools, insights, and market realities. Moreover, diversity-led innovation can’t be just a pet project of the HR department. The whole company must play a role in making it happen and capturing the value.

The Path Forward

When new statistics come out in business, people often get caught up in the details. The temptation is to look for evidence that validates a company’s current approach or (depending on where one sits in the organization) casts doubt on it. Diversity and innovation are complex areas of corporate activity, and we would expect that very few executives who review the new data will say that their companies are either doing everything right in either area—or everything wrong.

To us, the study’s most important finding is also its highest-level one: management diversity boosts innovation. It allows the discussion to move from the realm of “whether” to “what now?” And that’s when progress begins.