The world’s consumers love animal-based protein—so much so that in 2020 they ate 574 million metric tons’ worth of meat, seafood, dairy, and eggs—almost 75 kilograms per person. Moreover, the amount consumed is still increasing, especially in developing markets. Yet concerns about the environmental costs of growing all the animals we eat, how those animals are treated, and the consequences for human health of eating so much conventional protein are rising even faster.

That’s why alternative proteins have morphed in just the past few years from a niche product to a mainstream phenomenon. Plant-based meats are now a fixture at fast-food restaurants around the world, and plant-based milk is a household staple. Alternatives based on microorganisms have been available for decades, and you can taste meat grown from animal cells in restaurants in Singapore and Israel. Indeed, consumers will soon be able to make nine out of ten of the world’s most popular dishes—especially those using less-structured meat, such as ground beef—with reasonably priced alternative proteins.

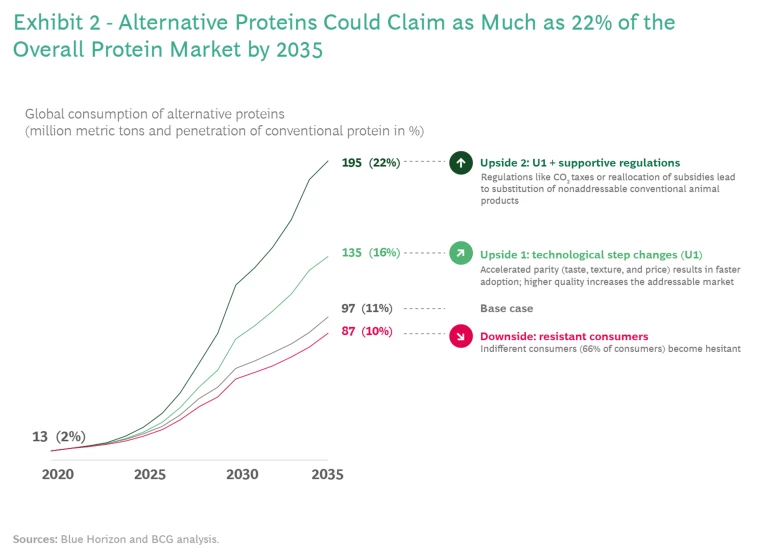

What we see today is only the beginning of the protein transformation, however. By 2035, after alternative proteins reach full parity in taste, texture, and price with conventional animal proteins, 11% of all the meat, seafood, eggs, and dairy eaten around the globe is very likely to be alternative. With a push from regulators and step changes in technology, that number could reach 22% in 2035. By then, Europe and North America will have reached the point of “peak meat,” and consumption of animal proteins will begin to decline.

The shift to alternatives can make a real contribution to the efforts to combat climate change.

In addition to its beneficial impact on human health, the shift to alternatives can make a real contribution to the efforts to combat climate change. By 2035, the shift to alternatives will save as much carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e) as Japan emits in a year, conserve enough water to supply the city of London for 40 years, and promote biodiversity and food security. Consumers can eat tasty food while helping protect the planet and making progress toward several of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Investors focused on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria can participate in a fast-growing market.

The protein transformation will depend, of course, on whether consumers are willing to try—and willing to continue eating—alternative proteins, and that will depend on advances in the technology for producing them at parity. In our report, we provide a first-of-its-kind market model, supported by discussions with more than 40 experts in the field, and an in-depth analysis of the technology behind alternative proteins. This in turn allows us to point to specific ways in which all stakeholders, from growers to producers to consumers and investors, can support and benefit from the protein transformation.

A Taste of the Future

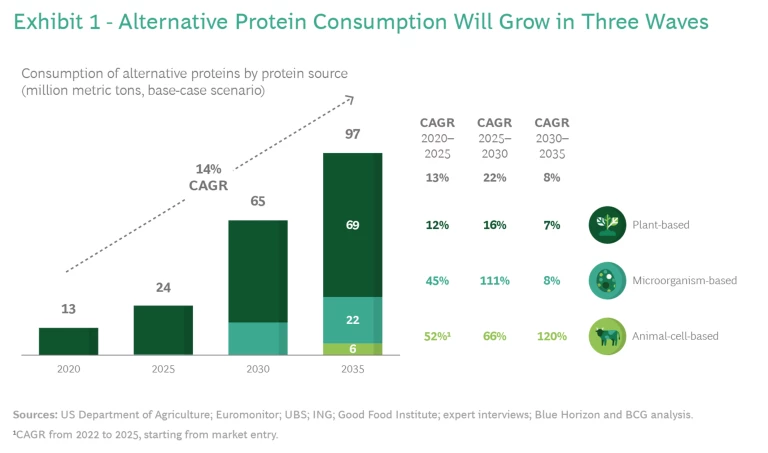

About 13 million metric tons of alternative proteins were consumed globally in 2020, just 2% of the animal protein market. We expect that consumption will increase to more than seven times that size over the next decade and a half, to 97 million metric tons by 2035, when the three types of alternatives will very likely make up 11% of the overall protein market. (See Exhibit 1.) Assuming average revenues of $3 per kilogram, this amounts to a market of approximately $290 billion.

Already, about 11% of consumers in the US, UK, and Germany are very interested in alternative proteins; 66% are somewhat interested, indifferent, or somewhat not interested; and only 23% are not interested at all, according to a recent study.

In short, alternative proteins must reach parity with animal proteins in three key areas:

- Taste. Alternative proteins must effectively imitate the well-known flavor—and smell—of meat, seafood, dairy, and eggs.

- Texture. Alternatives must also look and feel the same as animal proteins. The experience of eating meat depends largely on its fibrous structure. Fish appears flaky, cheese feels hard or stretchy. Alternative eggs and dairy must also behave like real eggs and dairy when being cooked.

- Price. At present, alternative proteins are usually not the bargain option, compared with animal proteins. If large groups of consumers are to repeatedly purchase alternative proteins, the cost must match or undercut that of protein from animals farmed under nonorganic conditions.

As Nick Halla, senior vice president for international at Impossible Foods, puts it: “You’ll buy the product once based on novelty, you’ll come back if the taste was good and if there are benefits such as nutrition and sustainability, and you’ll buy it in the long run if the value is right.”

Each of the three types of alternative protein is currently at different stages of parity with conventional proteins. (See “The Protein Mix.”) We expect that plant-based alternatives will achieve parity by 2023, those based on microorganisms by 2025, and those based on animal cells by 2032.

The Protein Mix

- Plant-Based. These are produced by extracting the protein from inputs such as soybeans and yellow peas, mixing it with additives for taste, then texturizing it to produce the right feel, usually through extrusion. Optimized crops, better and more natural additives, and optimized extrusion technologies will soon improve taste and lower production costs.

- Microorganism-Based. Here, protein is produced by growing bacteria, yeasts, single-celled algae, or fungi in a nutrient-rich medium, and then flavored and texturized into edible forms. Reducing the cost of the process will depend on improving the metabolic efficiency with which microorganisms convert their feedstock into protein and finding less expensive media.

- Animal-Cell-Based. These products are cultured directly from animal cells in a nutrient-rich medium in bioreactors. Formation of fibrous textures can then be triggered in a variety of ways, which are still in development. To reach parity, the speed and output of the culturing process must be improved and the media in which the cells are cultured must become less expensive and more efficient.

These dates will vary to some degree, depending on the type of animal protein being replaced. Plant-based burgers, for example, are very close to parity today and may reach it within the next two years. Plant-based chicken pieces, on the other hand, will likely only reach full parity after 2023. They are already close in taste and texture but need to get less expensive in order to compete with conventional mass-produced chicken. Microorganism- and animal-cell-based products will first reach parity with more expensive animal products such as meat; achieving parity with eggs and dairy will take more time.

Three Scenarios

Our base-line expectations for the growth of the alternative-protein market assume a consistent pattern of consumer acceptance, regulatory support, and technological change. How would changes in these assumptions affect the market’s growth? Significantly, and mostly on the upside, according to the alternative scenarios we developed (see Exhibit 2):

- Upside 1. Further efforts on the part of scientists, startups, incumbent food companies, and investors lead to technological step changes that improve product quality and accelerate the time to parity. Alternative proteins grow more quickly, to 16% of the market in 2035.

- Upside 2. More supportive policies and regulations, such as widespread taxation of greenhouse gas emissions and reallocation of agricultural subsidies to support the transition to alternative proteins, make alternatives substantially less expensive than conventional animal foods, pushing penetration to 22% of the market in 2035.

- Downside. Consumers who currently say they are ambivalent about protein substitutes become more reluctant to try them, slowing market growth by just 1 percentage point compared with the base case, to 10% of the 2035 total.

The Investment Perspective

Regardless of whether any of these alternative scenarios come to pass, substantial capital must be invested across the protein value chain to support the protein transformation. The extrusion capacity needed for plant-based proteins, for example, will require up to $11 billion to reach the baseline case of 11% adoption by 2035 and as much as $28 billion if the greatest upside scenario happens. Almost 30 million tons of bioreactor capacity for microorganisms and animal cells will also be needed in the base case, requiring up to $30 billion in investment capital—and far more in either of the upside scenarios. These are just two of the technologies required to unlock the market’s growth; the total capital needed will likely be much higher.

Substantial capital must be invested throughout the protein value chain to support the protein transformation.

Most investment capital is currently focused on companies that are integrated along the value chain, enabling them to ensure quality control while they explore new technologies. As the industry matures, however, two types of investment plays will emerge. The first is a technology play: a company that solves a particular technological challenge will likely become the go-to firm for its specific step along the value chain, such as flavoring, and other companies will eagerly license its intellectual property to augment their own processes. The second is a platform play: well-funded companies or investors will build industrialized platforms for capital-intensive technologies such as extrusion.

“In the coming years, speed to parity will be a key differentiator,” says Elizabeth Gutschenritter, Cargill’s managing director, alternative protein. “And to get that, you need both technological developments and large-scale manufacturing platforms. The tech winners usually get the headlines, but the industry shouldn’t underestimate what it will take to scale manufacturing.”

Conclusion

The benefits of alternative proteins are clear—lower carbon emissions, fewer concerns about the ethics and environmental consequences of intensive animal farming, as well as tasty, nutritious, and healthy food. Consumers can rest assured that they are contributing to the UN’s SDGs, while ESG-oriented investors can participate in the growth of a major new industry.

Farmers and scientists are at the heart of the transformation, providing the technological means and the quality inputs needed. Incumbent food companies and startups will refine and scale production to make alternatives tastier and less expensive, securing market share in the race to parity. Consumers will demand more enjoyable alternative proteins. Investors with the right vision and expertise can fund the transformation and participate in every step of the value chain. Together, they can benefit from a $290 billion market as they build a more sustainable food system that tastes good, too.

Disclaimer

In particular, neither BCG nor BHC provides any legal advice, medical advice, nutritional advice, tax advice, or accounting advice. Further, evaluations, market and financial information, and any kind of conclusions contained in the Opinion are not definitive and are not guaranteed by BCG nor BHC. The recipient is responsible for obtaining independent advice concerning these matters. Further, third parties may not, and it is unreasonable for any third party to, rely on these contents for any purpose whatsoever. Any reproduction, distribution, editing, and exploitation of the BCG content, in full or in part, published in the Opinion requires the prior consent of BCG. Neither BCG nor BHC is obliged to update the contents or to make any corrections.