On average, asset managers commit more than 25 percent of costs to IT and operations. Yet, in many cases, those functions don’t receive even a quarter of the company’s time and attention. As a result, most managers’ operating models evolve piecemeal, without being explicitly anchored to the company’s vision or strategy.

Global Asset Management 2014

- Steering the Course to Growth

- Differentiation Begins with a Target Operating Model

- Insurers Attack the Target-Operating-Model Opportunity

This incremental approach might seem to work for a while, but it leaves managers at increasing risk of being left behind. Clients and products proliferate, new markets are entered, footprints extend globally, and acquisitions bring new technologies that are patched onto legacy systems. In the new new normal of regulatory overload, shifting investor preferences, and competitive digitization, such haphazard evolution can quickly morph into a cripplingly complex tangle of systems and processes.

Most asset managers try to get by with such patchwork operating models. But they are light-years from achieving the enormous potential benefits of a strategically conceived target operating model that leading competitors have defined for themselves and are moving toward.

Broadly defined, a target operating model is an overall operations and technology ecosystem that allows a company to chart a path for achieving its strategic vision on the basis of its priorities and starting point. When an operating model becomes a critical part of a manager’s strategy, the benefits are tangible and the profound business impact can include the following:

- Shorter time-to-market cycles due to greater agility in launching new businesses and trading new products

- Better ability to ramp up volume quickly at minimum marginal cost

- Increased client satisfaction due to a more transparent and compliant operating model

- Superior investment performance, from focusing investment management resources on priority growth areas and supporting them with tools, data, and insight

- Reduced risk from a more controlled and stable operating environment

- Greater long-term cost-effectiveness

In contrast, managers who fail to act might lag behind as they deploy increasingly greater resources simply to manage the tangle. In many cases, inaction inhibits growth because of the exponential costs of adapting technology and processes to the flow of new regulations; the inability to trade in new asset classes, markets, and locations; and an increased operational risk profile.

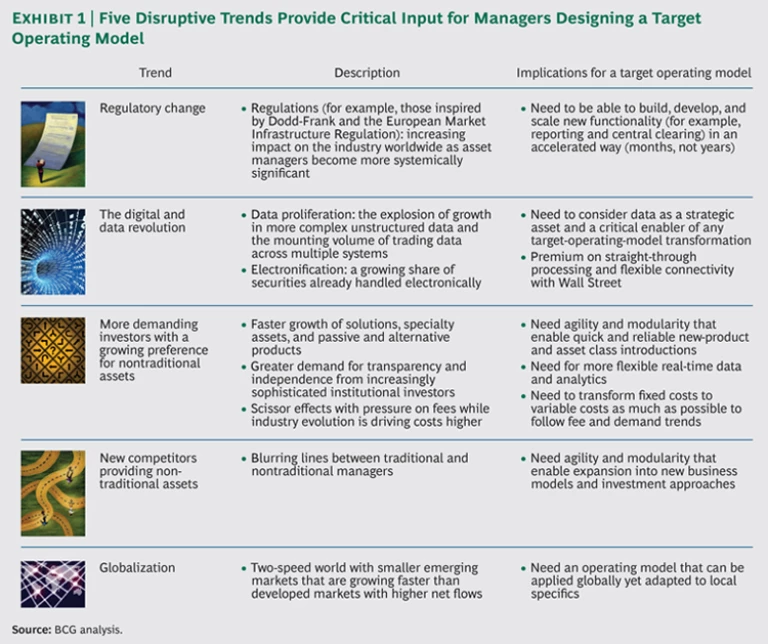

Trends Reshaping Asset Management and Its Operating Models

While the new new normal reshapes financial services, managers will find that the five disruptive trends introduced in Global Asset Management 2014: Steering the Course to Growth provide critical inputs as they define their target operating model. (See Exhibit 1.)

Many asset managers invest insufficient time in defining how they will translate their strategic vision into an operating model that takes into account their starting point, resources, and priorities. The path to achieving that goal begins by creating a target operating model.

The first step in defining the model is to understand the company’s strategic vision and priorities for the next five to ten years. The answers to the following questions can help frame the process:

- What is your business strategy—in broad brush and detail?

- What markets, products, and segments will you compete in?

- How do you implement your investment philosophy to win?

- What is your differentiated client value proposition?

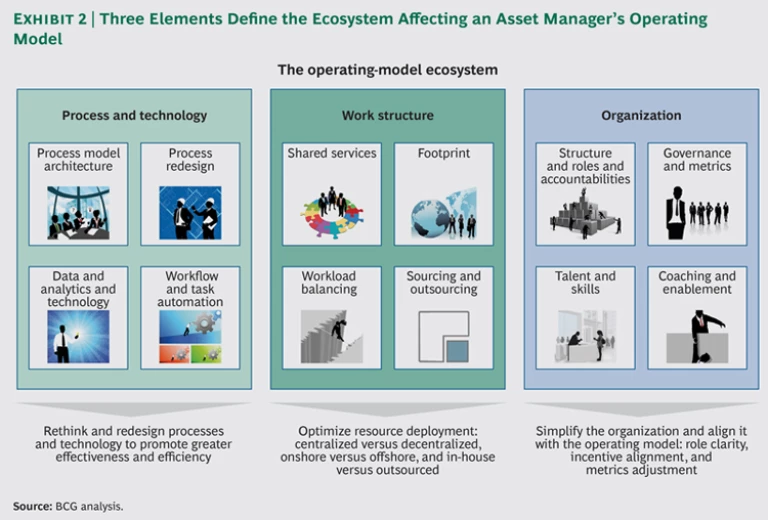

Once the company has agreed on its strategic vision, it will need to analyze its operating-model ecosystem in order to define how to achieve the vision. Ecosystems vary by company, location, and asset type.

Our definition of operating model is based on three elements: process and technology, work structure, and organization. (See Exhibit 2.)

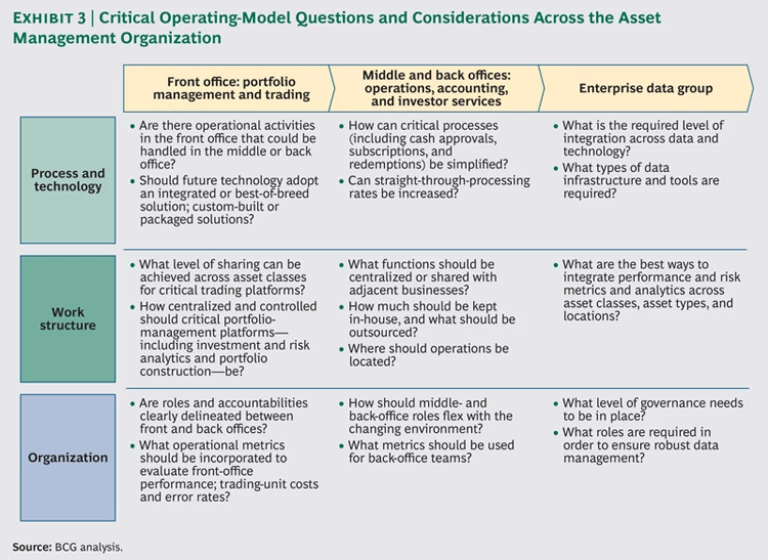

These three elements translate into a series of far-reaching business questions and decisions for the front office (including the level of sharing across trading platforms), middle- and back-office operations (such as the appropriate degree of outsourcing and centralization), and the enterprise data group (including governance and the level of real-time integration). (See Exhibit 3.)

A World-Class Target Operating Model

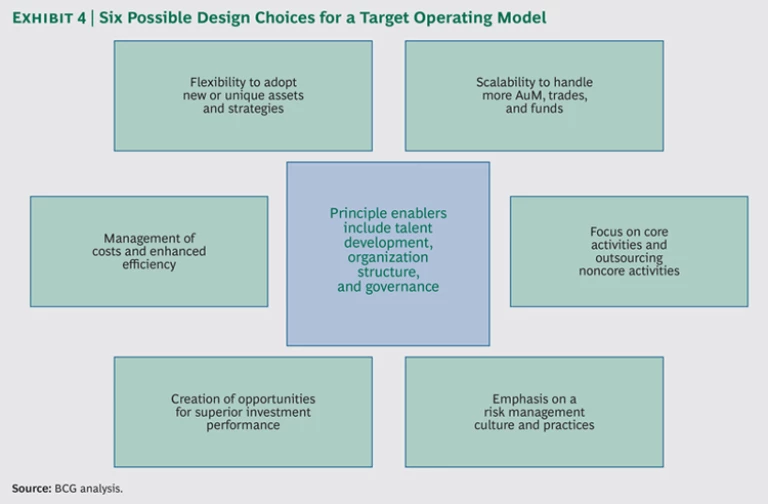

There is no single, ideal target operating model that fits all managers. Rather, the design of each company’s model will depend on the company’s starting point, history, and the optimization goals it has prioritized.

However, agreement on these optimization goals must be explicit and shared at all levels of the organization—not just within the operations and technology silos.

We generally look at six possible design choices for a target operating model, and the selection of a particular model depends on the organization’s optimization goals. (See Exhibit 4.)

The relative weight to assign each of these design choices varies by manager and asset type. For example, a manager of passive products would focus on responsiveness, scale, and efficiency. An active asset manager would likely stress a flexible and adaptive model. An asset owner might emphasize the importance of having a single view of performance and risk across investments. Insurance company asset managers, who oversee the world’s second-largest asset pool, could be seeking business upside, risk, and efficiency.

Truly world-class operating models will deliver value across multiple elements, reconciling often opposing forces such as scalability and flexibility.

To illustrate, we have selected four operating models that we find particularly interesting and innovative. Although these models must be consistent with the objectives of a particular company, their core characteristics have valuable lessons for other asset managers.

Shadow Outsourcing: Redundancy. Outsourcing core processes and technology has become standard, but in many cases, asset managers decide to keep some aspect of quality control and oversight in-house. Now a small number of innovative asset managers have begun to outsource such “shadow” capabilities. The goals are to focus on core activities and improve risk management culture and practices through increased independence and better quality control. Shadow outsourcing also makes it easier to switch outsourcers. (See “Emergence of the Shadow Outsourcer.”)

Emergence of the Shadow Outsourcer

Although it has become standard to outsource processing capabilities, many companies keep a “shadow” of such operations in-house for oversight and quality control. Now a small number of hedge funds have begun to outsource this shadow responsibility, using two providers simultaneously. This model merits consideration by traditional asset managers as well.

This dual-outsourcer model is particularly relevant given today’s high premium on transparency, risk management, regulatory compliance, operational risk, and variable costs. It also responds to emerging regulatory requirements in Europe and the U.S. for better business-continuity planning—that is, the ability to substitute a new service provider for one that, for example, fails to perform well or goes out of business.

The outsourcer model is structured so that an execution partner and a shadow partner operate and control, respectively, the middle- and back-office operations. The execution partner is responsible for operating those functions and manages the official books and records. The shadow partner is responsible for replicating critical functions of the middle- and back-office operations, reconciling and resolving differences with the execution partner, and providing an independent quality control of the execution partner’s results.

This model removes the requirement to maintain an internal oversight team and the associated technology and tools required to perform a controlling function for the most critical and risky activities.

Variations of the model range from full shadow to light shadow.

- Full Shadow. Both outsourcers operate the full scope of processing and accounting, although only the primary outsourcer interfaces with counterparties. The asset manager achieves full “switchability”—the ability to move from one outsourcer to the other quickly.

- Partial Shadow. The shadow outsourcer duplicates and verifies only the most critical functions—such as valuation and reconciliation—which are typically replicated in-house. This model is less costly and simpler to implement, but it provides limited switchability.

Cost is among the obvious questions about the dual-outsourcer model. The usual, though incorrect, expectation is that two outsourcers cost twice as much as one and, thus, that having two is financially prohibitive. This notion fails to account for the true costs of personnel, technology, maintenance, network hardware, and office space that come with internal shadowing. On the basis of service provider discussions and our modeling, we believe that the dual-provider model can deliver significant additional value of 5 to 25 percent more than the all-in cost of the single-outsourcer model with an in-house shadow operation. In the long run, the cost of maintaining an up-to-date internal shadow function will continue to grow. These rising costs, coupled with the increasing scale of the outsourcers, will likely drive the cost benefit even further.

The value of the dual-outsourcer model is compelling because it provides the following benefits:

- Increased transparency and independence in client-sensitive areas of positions and valuations, whose importance was highlighted by the recent crisis

- Quality assurance that is the result of having two reputable independent outsourcers

- A healthy competitive tension between outsourcers, supporting ongoing service quality

- Evolution of internal roles from processing to higher-value and differentiated strategic-partner management

- Elimination or reduction of ongoing technology investments

- Ability to switch providers quickly if an outsourcer does not deliver the expected level of service or goes out of business

The dual-outsourcer model is very new. At this stage, we don’t believe that it applies to every asset manager or asset owner. However, we do believe that it has potential appeal for sophisticated managers and asset owners as well as large hedge funds.

The Global Operating Model: Global Scale, Local Customization. This model aims to achieve twin objectives: scalability, by taking advantage of an institution’s global scale, and management of cost and efficiency, by, for instance, leveraging lower-cost locations. The global model is also a powerful means of creating a template for future expansion to new regions.

This model relies on a global infrastructure comprising core, fully integrated front-to-back systems, single repositories for reference and market data, and common operational processes. The industrialization of systems, repositories, and processes creates scale benefits while accommodating the customization required by individual investment-management teams and regions.

Another benefit is the creation of shared services of critical functions—such as data management, technology, and recon-ciliations—in lower-cost locations as a

way to build scale and reduce unit cost. However, location-dependent functions—such as trading and regulatory reporting—and those needing proximity to portfolio managers or clients remain within local or regional hubs.

The Utility Operating Model: Monetizing the Model. The manager’s premise in this case was to create a customizable, flexible operating model that would allow for the addition of volumes and new products at minimum marginal cost. After investing heavily, the manager created world-class middle- and back-office operations that would have value for others and looked for ways to pool future costs and investments and to generate additional revenues.

The solution was to turn the multiyear investment into a service-providing business. The company commercialized select “com-moditized” portions of the operating model as a “utility” service for competitors. Two functions that differentiated the company—front office and data—were of course kept off limits.

Data-Centric Operating Model: Real-Time Decision Making. The manager’s primary objectives for this model were threefold: to maximize flexibility for new and unique assets and strategies, to improve the risk management culture and practices (for instance, by providing increased transparency and a better risk view across assets), and to create superior investment performance through better use of data in investment decisions.

Delivering on this goal requires a technology-heavy operating model and a real-time data capability feeding a modular technology and operations platform.

This last model reinforces the strategic importance that data occupies in target-operating-model transformation. In many cases, transformations are enabled by data infrastructure. Mature data-management practices are formidable enablers that allow a high level of automation and near-real-time analytics. (See “Recognizing Data as a Strategic Asset.”)

Recognizing Data as a Strategic Asset

Most asset managers have considered improving their data management, but their progress along the data maturity curve has generally been slow.

We classify data maturity into three levels—controlled chaos, managed, and optimized. (See the exhibit below.) In BCG’s Global Asset Management survey, about 60 percent of respondents rated themselves in the lower levels of the data maturity curve. This implies that most managers have not yet embarked on formal data-management programs or that they have done so only with single, localized initiatives.

Nonetheless, managers overwhelmingly recognize the value of improving data management practices. The majority of our respondents were in the lower levels of maturity, but all planned to achieve high levels within three years. For most, this will mean a step change advance, requiring substantial attention and investment, from where they are today.

Better data management has the potential to enable operating-model improvements in several ways. On the revenue side, data management can create flexibility in investment strategies and improve investment performance—for example, identifying trade opportunities by mining social-media preferences or integrating risk management analysis across locations and asset classes. It can improve customer acquisition through more targeted marketing while supporting a better customer experience through a customized and all-inclusive view of holdings.

On the cost side, leaders in data management can improve efficiency by removing manual processes from data cleaning and consolidation. They can achieve flexibility and scale in navigating market change—including meeting new regulatory reporting requirements, introducing new asset classes, and delivering custom client reporting.

For most organizations, the step change required to extract the most value from data can be achieved only by undertaking a data transformation. Companies embarking on a data transformation face the challenge of balancing investments in both foundational initiatives and improvements that support business needs. In weighing these trade-offs and to achieve success, companies must be sure that data transformations are clearly aligned with business strategy so that foundational initiatives can be traced to a business need.

Successful organizations will capitalize on data improvements and derive significant business benefits. But the road to achieving a state in which data is a strategic asset can be difficult. Data improvement programs risk morphing into multiyear IT-investment projects that are costly but lack clear business benefits. Successful organizations will not achieve data maturity for data maturity’s sake: they will clearly understand and articulate the strategic value of their data and make investments appropriate to their situation.

Seizing the Moment

Target-operating-model transformation is a multiyear journey, not a big-bang, do-it-all-now endeavor. Indeed, although transformation must be aggressive, it should entail a series of realistic and achievable steps. Each step should deliver clear and tangible benefits to clients, to the business, and to overall financial results. Several actions are crucial to the success of a target-operating-model transformation program:

- Lead from the top. Transformation should rank among a company’s top two or three initiatives. It should be championed by the CEO and regularly discussed by the management team. The senior sponsor—typically the CTO or COO—should have a seat at the table.

- Anchor to business priorities. Target-operating-model transformation is much more than an IT or an operations transformation. It is a critical enabler for the business, especially for front-office professionals. Their buy-in and engagement throughout the transformation is crucial.

- Fund the journey. The transformation will need to deliver tangible results early and have a self-funding business case.

- Involve the A-team, both internal and external. A target-operating-model transformation is a large and complex project involving business, operations, IT, and corporate functions. It requires the best talents internally as well as deep partnerships with vendors, including outsourcers, IT vendors, integrators, and strategic advisors.

Now is the time for asset managers to redefine their operating model—from top to bottom. Many have started the journey timidly, focusing only on the back office rather than committing to a complete transformation.

In a rapidly evolving industry, asset managers that invest the resources to transform their operating model will differentiate themselves among clients, enable superior performance and growth, and capture market leadership.