In nautical terms, trimming the sails means making adjustments that allow a boat to get the most power from the wind. That’s precisely what treasury functions need to do. After a tumultuous decade, market and regulatory pressures have eased slightly. While treasuries may relish the chance to catch their breath, they cannot become complacent. They must use this period to begin storm-proofing their operating models and advance digitization. Markets are cyclical. In time, another downturn will command round-the-clock attention. Business models are also changing as banks respond to new competitors and new technologies. Treasuries that take advantage of the relative stability now to improve governance, enhance front-office visibility, shore up needed knowledge and skills, and provide the right data and IT infrastructure will help their banks ride the waves of disruption and become more competitive and more profitable.

Our 2018 Treasury Benchmarking Survey looks at how treasury organizations have weathered the past two years and what it takes to trim the sails. A total of 44 banks across Europe and North America participated in our study, including 10 global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), 19 banks with balance sheets of €200 billion or more, and 15 regional and midsize players with balance sheets of less than €200 billion.

Treasury Has Evolved over the Past Ten Years

This 2018 benchmarking survey is the fifth in a biennial series spanning the past ten years. That decade-long view provides a helpful vantage point from which to observe how treasuries have responded to one of the most challenging periods in banking history. For most, it has been a journey of significant and, in some cases, profound change.

For most treasuries, the past decade has been a journey of significant and, in some cases, profound change.

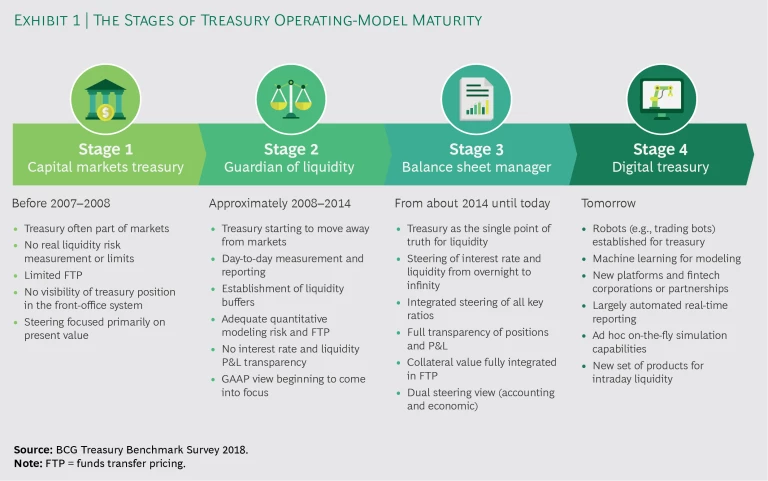

Prior to 2008, for instance, many treasury functions were housed within capital markets divisions and run like a trading business because liquidity at the time was considered an ample resource with no set limits. The financial crisis changed that. In the years that followed, many treasuries began moving out of capital markets and taking on a greater strategic or steering role for managing the balance sheet. With liquidity management crucial to bank viability, treasuries began to systematically identify liquidity risk and establish better day-to-day methods to measure, monitor, and manage it.

The past ten years also saw a new slate of banking regulations introduced. Managing the increased regulatory volume kept bank treasuries consumed with compliance activities, work that included implementing new coverage and funding ratios, conducting stress testing, managing asset encumbrance, and building appropriate liquidity buffers.

The macroeconomic environment presented its own challenges. For much of the decade, a sluggish economic recovery diminished investor appetites and led to a sustained period of low—and sometimes even negative—interest rates in most major markets, pushing treasuries to reduce costs and improve how they manage the banking-book position.

The resulting changes constitute significant improvements in overall treasury maturity. Our survey found that 50% of respondents now rate their treasury functions as having reached stage 3 in our four-stage assessment of treasury maturity, with stage 1 being the least advanced and stage 4 being the most, meaning they have achieved greater structural balance and visibility in managing the bank’s treasury positions and their own profit and loss (P&L) contribution. While that is encouraging, the remaining 50% indicated that they are still somewhere between stages 2 and 3, and none have achieved stage 4. (See Exhibit 1.)

Survey trends suggest several priority areas for treasuries as they work to improve management and oversight.

Governance for the banking book continues to centralize. In keeping with the steering-oriented focus that has become predominant across banks, oversight of all banking-book risks—including liquidity, foreign exchange, credit spread, and interest rate risk—continues to shift to treasury. Treasuries are also becoming the primary manager of the bank’s financial resources as they gain increased responsibility for liquidity, funding, capital, and the balance sheet. With that expanded financial-oversight role, the number of treasury units reporting directly to the CFO has grown significantly. Our 2018 survey found that 75% of treasurers now report to the CFO, compared with less than 20% ten years ago. (The exceptions are those in treasuries that have historically played a significant execution role.)

Execution activities increasingly fall under treasury’s purview. The majority (80%) of survey respondents reported that treasury manages the bank’s money market activity, up from 60% in 2014. In addition, where treasuries once predominantly used money markets as a profit center, many now rely on them to support liquidity management. This is because the implementation of regulatory reforms such as the liquidity coverage ratio and leverage ratio—in addition to the bank levies charged by some national regulatory authorities—has made money market trading less profitable and liquidity management more important.

In keeping with this integration trend, 65% of repo desks now sit within treasury and 50% of treasuries reported that they have a mandate to access markets directly to execute interest rate risk hedge trades. This shift reflects the fact that, for many treasuries, the majority of interest rate risk now comes from the banking book. Also, market making in interest rate derivatives requires scale, which means that smaller banks can no longer compete against larger banks in this area.

Lines of defense continue to sharpen. Treasuries are working to improve how they segregate oversight responsibilities, but practices vary by region.

Treasuries are working to improve how they segregate oversight responsibilities, but practices vary by region.

In Europe, roughly 50% of treasurers said they run model development and stress testing within the first line of defense, where treasury manages the risk, and the other 50% include it in second-line functions. While no standard operating model has yet emerged, our analyses suggest that European treasuries are increasingly moving toward housing model development within the first-line function.

In the US, by contrast, there is much greater uniformity: 90% of survey respondents said they place interest and liquidity modeling in their first-line defenses, while model validation sits within the second line. The standardization is a result of regulatory pronouncements, such as the Federal Reserve Board’s Supervisory Guidance on Model Risk Management (SR 11/7), that advocate this type of risk

delineation.

Visibility gaps prevent treasuries from assessing the bank’s risk position. While survey respondents have made improvements in the way they categorize and view risk, with approximately two-thirds of treasuries reporting that they can now split risk types, only 50% of survey participants said they have daily insight into their entire banking-book position. Likewise, only a small number of banks have real-time data feeds to oversee their loan portfolio and deposits. Most treasury functions report that they need to use multiple systems to get relevant information, and much of the analysis continues to rely on manual labor.

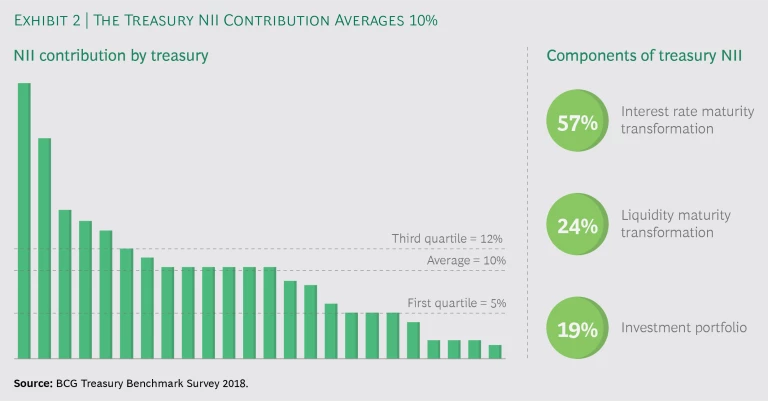

Treasury Contribution Continues to Average 10% of Bankwide Net Interest Income

Treasury P&L plays a crucial role in helping banks to maintain stable net interest income (NII), but value generation varies depending on risk strategy, risk appetite, and the makeup of the treasury function, such as whether it manages the money market and repo desk.

While these factors can result in P&L variance, with some treasuries contributing zero P&L to NII in 2018 and others as much as 30%, the average contribution across all respondents continues to be 10%—similar to the average reported in both our 2014 and 2016 benchmark surveys. (See Exhibit 2.) In terms of composition, about 60% of the average treasury P&L comes from pure interest rate mismatch and 25% comes from pure liquidity maturity transformation. The remainder comes from the liquid asset buffer, a dedicated investment portfolio, and other sources. Surprisingly, several survey participants still cannot measure their treasury P&L or the P&L components that are reallocated to the business units.

As we delved deeper, survey data revealed that next to structural liquidity and interest rate maturity transformation, three factors play a particularly big role in influencing treasury P&L strategy and performance.

Low rates prompt a search for growth. Roughly 60% of treasurers employ a dedicated investment portfolio, which usually consists of bonds issued by financial institutions, covered bonds, high-quality corporate bonds, and sometimes even equity investments. The size of these portfolios has grown in recent years as treasurers—especially those in Europe—seek to offset the impact of the low-interest-rate environment. Some also lowered their liquidity buffer risk appetites to support higher investment portfolio risk tolerances.

Liquidity buffers continue to grow. In 2010, liquidity buffers accounted for approximately 10% of the average cash balance sheet; 2018 survey data found that they now constitute 19%. The growth is due in part to regulatory requirements that mandate certain liquidity coverage ratios and in part to the fact that sustained low market rates have presented relatively few attractive investment alternatives. Growing buffer sizes create opportunity cost: instead of increasing their core credit business, banks are holding a greater number of high-quality liquid assets (HQLAs), which can come with a negative carry (meaning that holding costs exceed income earned).

Funding tenors have also grown over the past decade, increasing from an average of 6 to 12 months in 2008 to an average of 18 to 24 months in 2018, which has added to buffer costs. Lowering those costs requires treasuries to have granular cash flow data and tools to forecast cash movements more accurately, along with transparency about the true value of highly liquid assets and tools to support investment decisions in the most valuable HQLAs.

Treasuries need to move from the risk aversion mindset that dominated much of the past decade to a value mindset that will make them more resilient.

Forecasting intraday liquidity remains difficult. While treasurers are focused on improving the steering and pricing of intraday liquidity, many said that forecasting working-capital demand continues to be challenging. There is wide variation in the amount of working capital that banks are holding against intraday outflows: amounts range from 0.8% to 13.5% of cash balance sheets. While reporting of the intraday liquidity position according to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s standard 239 has improved internal risk-reporting practices, treasuries must continue to strengthen their cash management forecasting capabilities. As they look ahead, about half of respondents said that they expect to see new intraday products such as intraday swaps, deposits, and money market products become available as the enabling technologies mature.

It’s Time to Optimize the Treasury Operating Model

With global markets largely stabilized, banks now have breathing room to focus on improving the maturity of their treasury operating models. In doing so, treasuries need to move from the risk aversion mindset that dominated much of the past decade, when bank survival was at stake, to a value mindset that will allow them to become more resilient. (See “ Enhancing the Strategic Potential of Treasury ,” BCG article, August 2017.)

Here’s what it will take to trim the sails.

Establish a clear mandate. Treasuries have always played a prudential role to protect the bank and stabilize NII. To maximize value generation and risk management, treasurers must have full transparency and oversight into all banking-book risks and P&L drivers. That’s true regardless of whether the treasury mandate emphasizes resource allocation or optimization, whether treasury is a profit center or not, and whether treasury simply executes asset liability committee (ALCO) decisions or has the freedom to optimize. Creating that structure and steering it effectively require that treasury has leadership consensus to govern in this way, the knowledge and skills to do it well, the ability to examine the treasury position on both an economic and an accrual basis, and clearer delineation between risk types and between treasury and the risk department.

Close the expertise gap. Survey data found that large banks had a median of 35 FTEs for every €100 billion on their cash balance sheet, regional banks a median of 43 FTEs, and GSIBs (which typically have better economies of scale) a median of 24 FTEs. Regardless of bank size, however, survey data found that treasury FTEs are divided fairly evenly across steering and execution functions. Looking ahead, staffing composition will need to become more nuanced.

Looking ahead, staffing composition will need to become more nuanced.

The growing complexity of balance sheet and bank operations will require treasury to acquire specialized subject matter expertise. Risk management, agile development, process, and application design skills will become especially important along with data scientists and business “translators” who can work closely with treasury and IT to explain needs and priorities. Meeting these needs will require treasuries to inventory their existing skill base, identify crucial gaps, and incorporate hiring and development planning into their change management processes.

Acquire visibility across the banking book. Some treasurers view the banking book primarily through an accrual lens, while others favor a full economic or fair-value view. But maximizing value generation and risk management will require treasurers to manage the banking book from both angles because the accrual view looks at fixed periods and is the basis for NII and other comprehensive income (OCI) steering while the economic view factors market rate movements and economic sensitivities (such as interest rate and credit spread movements) into the steering decisions.

Treasurers will also need to establish clearer distinctions between risk types and separate liquidity risk from interest rate risk and credit risk. In addition, they must improve their ability to steer nonlinear risk (especially optional financial components such as mortgage prepayments) so that they can adjust positions on the basis of a more complete assessment of risks and value drivers.

Leading treasury functions intent on improving their P&L contribution will need to acquire the analytics, data integration, and predictive-modeling capabilities to enable a comprehensive view of the entire banking book.

Integrate key data and systems. Survey data found that treasuries that historically had a strong market execution focus tend to use front-office systems that support daily economic-position management and those with an accrual focus tend to use asset liability management (ALM) systems for daily position management and front-office systems for trade capturing. Even treasuries that take a blended view still struggle with fragmentation. Many use a front-office system for daily economic-position management and an ALM for periodic (weekly or monthly) modeling and sensitivity analysis.

Yet each of these setups brings challenges. While front-office systems are great at tracking market movements, they typically lack the analytics and processing power to support the complex simulations, sensitivity analysis, and periodic steering that treasurers increasingly need. Likewise, while ALM systems offer more-robust computing power, they generally lack the needed front-office functionality.

Jockeying between different types of data systems can introduce error and requires significant manual intervention.

Jockeying between these two systems is not ideal either because that requires treasury teams to continually upload daily position management data and then rigorously reconcile the information—efforts that can introduce error and require significant manual intervention. In addition, many treasuries suffer from rigid IT and noninteroperable software. Basic functionality like cash flow or valuation management often has to be replicated in different systems to compensate for these gaps, creating huge data reconciliation challenges and increasing operational risks.

To address these issues, treasuries must commit to creating a modern, flexible IT environment, capable of supporting application programming interface (API)–enabled microservices such as valuations or cash flow generation.

Embrace digitization. Treasuries are not immune to the digital transformation sweeping the broader banking sector, but many have been slow to embrace it because they’ve been besieged by more-pressing issues over the past several years. Now, bank treasury departments have the opportunity to make up for lost time.

Technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, blockchain, robotics, and data capture techniques (such as optical character recognition [OCR] and voice and speech recognition [VSR]) have the potential to help treasury departments optimize their activities. Process automation can help alleviate excessive manual effort, putting many day-to-day tasks on a competent autopilot. Basic automation is a first step that could deliver significant efficiency gains, reducing operating costs by 20% to 30% over the next three to five years.

Overall performance—in terms of deeper risk management insights and better decision making—could outweigh efficiency gains by a factor of five to ten and raise the average treasury NII contribution by 10% to 15%. Although the application of distributed-ledger technology for treasuries is in its early stages, treasuries can still make big strides in advancing their digital maturity by applying machine learning to analytical and forecasting tasks. Many treasuries have implemented data capture techniques to improve their collateral optimization and repo-trading processes. Those that have not should prioritize the development and deployment of those solutions to inform their activities.

Riding the Seas of Change

Treasury departments must ensure that their operating models are nimble enough to sustain a stable P&L performance and resilient enough to withstand potential disruptions as new competitors and new technologies enter the arena. Working harder and faster won’t be enough. Treasuries need to work smarter as well. Future-proofing the treasury function will require new skills, tools, and capabilities as well as a strong, modern, and flexible IT foundation. Treasuries that take advantage of the current calm in the market to lay that groundwork will help ensure smoother sailing for their institutions in the long term.