W ill job security erode with the advance of a digital “gig economy”? Will freelance workers, bereft of traditional benefits and social safety nets, face a diminishing share of income and wealth?

The gig economy is often perceived as a fast-growing threat to employment stability and labor rights, promoting low-grade, low-paid jobs that offer workers little of the appeal or dignity of traditional employment. Public policy discussions and media articles often portray digital labor-sharing platforms—such as Uber, TaskRabbit, and Upwork—as a rapidly expanding source of real or potential exploitation, undermining the job and social security infrastructure established in mature economies a century ago. In an April 2017 editorial, the New York Times concluded that gig platform companies “have discovered they can harness advances in software and behavioral sciences to old-fashioned worker exploitation.”

To understand the extent to which those fears of disruption and exploitation are grounded in reality, the BCG Henderson Institute, as part of its Future of Work project, conducted a large-scale global survey of workers with the support of Research Now SSI, and additional supporting research. Our survey sample intentionally included a significant portion of workers with pay and education levels below the average in their countries. We included these respondents to reflect the views, needs, and employment circumstances of the workers potentially most vulnerable to disruption, and to avoid the risk of artificially rosy findings. Our sample also comprised workers in a rising wave of what we call the new freelancers—that is, those who find temporary work through digital labor-sharing platforms. This group, a product of our era’s ongoing digital disruption, is often perceived as the disenfranchised vanguard of the gig economy. (See “Accounting for Vulnerable Workers.”)

ACCOUNTING FOR VULNERABLE WORKERS

ACCOUNTING FOR VULNERABLE WORKERS

In May 2018, the BCG Henderson Institute and Research Now SSI conducted a survey of 11,000 workers in 11 countries: the US, the UK, Germany, France, Spain, Sweden, Japan, India, Indonesia, China, and Brazil.

The sample of 1,000 per country was designed to exclude highly educated workers—those with bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees, and above—and to include a large share of people with lower incomes. Among respondents, 60% to 85% had house- hold incomes below national averages, and just 29% had two to three years of college—the highest level we included.

Our sample represented a full range of age groups and work situations, including salaried employees as well as part-time, temporary, and short-term-unemployed workers.

The goal was to understand respondents’ perspectives on their professional situations, the forces shaping the workplace that are currently affecting them, or that they expected to affect them, and how they intended to adapt.

Our research specifically assessed workers’ experience with freelancing and online gig work. We asked all 11,000 respondents if they currently offered their labor on gig platforms. To avoid misinterpretation, our survey listed by name the most widely used gig sites in each country. It asked respondents if they used these or similar platforms to source work for themselves.

The survey results, along with a separate survey of executives in diverse industries and interviews with company leaders and with founders and executives of labor-sharing platforms, offer a more nuanced view of the emerging gig economy. In particular, our research underscores the significant opportunities—for workers and companies alike—to benefit from it. Many of the new freelancers we surveyed are embracing the trend as a path to greater autonomy and more flexible and meaningful work.

Our research underscores significant opportunities—for workers and companies alike—to benefit from the gig economy.

For companies, the findings highlight that gig platforms increase access to new, high-tech skills and sorely needed workers of many types who are difficult to source through traditional labor markets.

More broadly, our research reveals that gig work is just one element in an emerging ecosystem that includes other evolving forms of work—such as temping, contracting, and self-employment—along with a variety of support services. The result is profound change in the way companies hire, train, reward, and manage employees.

The new freelancers—a product of our era’s ongoing digital disruption—are themselves beneficiaries as well as victims of disruption. This balance between disruption and opportunity emerged on a personal level in the responses to our worker survey: the number of workers who reported losing their job to the freelancing trend equalled the number who regained employment by the same path. More than 30% of those who returned to work credited online gig work with enabling them to rejoin the workforce.

Amid such turbulence, despite no net losses of jobs, it’s easy to focus on the resulting discomfort. Yet disruptive change is also forcing greater overall adaptiveness in the employment system, creating fresh opportunities in traditional labor markets and at companies.

Taking the Real Measure of the Gig Economy

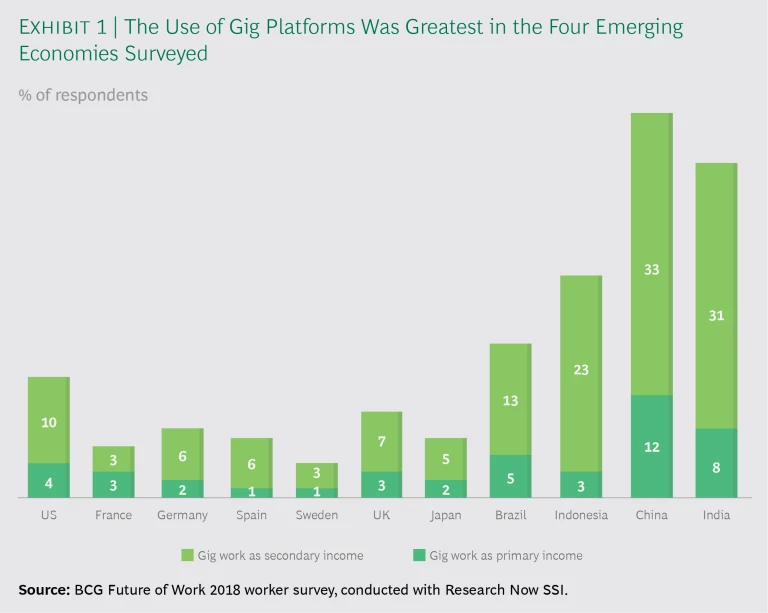

While the gig economy is often described as a large and rapidly growing global phenomenon, it remains relatively small by some important measures. Our research shows that workers’ use of labor-sharing platforms as their primary source of income is still relatively modest, particularly in mature markets. In the US, Germany, Sweden, the UK, and Spain, just 1% to 4% of workers cited gig platforms as their primary work source. The share of primary-income gig workers has remained stable across most of Europe for half a decade, according to a 2016 report by the OECD’s Institute of

However, gig work’s portion of the overall labor force was greater in the four developing markets in our survey—China, India, Indonesia, and Brazil. The share was biggest in China, where 12% of workers said they earned their primary income through digital platforms. This higher share no doubt reflects the larger proportion of informal employment in emerging markets. Still, it shows that workers in those markets have adopted labor-sharing platforms faster than workers in mature markets.

Measuring gig work only as a primary source of income, however, may underestimate its true size and growing global significance. An additional 3% to 10% of workers in mature economies, and more than 30% in some developing countries, reported using gig platforms as a secondary source of income. (See Exhibit 1.)

Corporate executives worldwide recognize that the rise of the new freelancers will have a significant impact on their workforces. In a 2018 survey of 6,500 executives worldwide, conducted by BCG in partnership with Harvard Business School’s Managing the Future of Work initiative, roughly 40% of respondents said they expected freelance workers to account for an increased share of their organization’s workforce over the coming five years. And 50% agreed that corporate adoption of gig platforms would be a significant or highly significant

These results are consistent with research, published in May 2018, by SAP Fieldglass, a provider of cloud-based external workforce management solutions, conducted in collaboration with Oxford Economics. Of the 800 global senior executives surveyed, 38% were using on-demand, online marketplaces to source freelancers. The study predicted that companies’ adoption of these platforms would nearly double in three years.

Alexa, Get Me a Freelance Software Designer

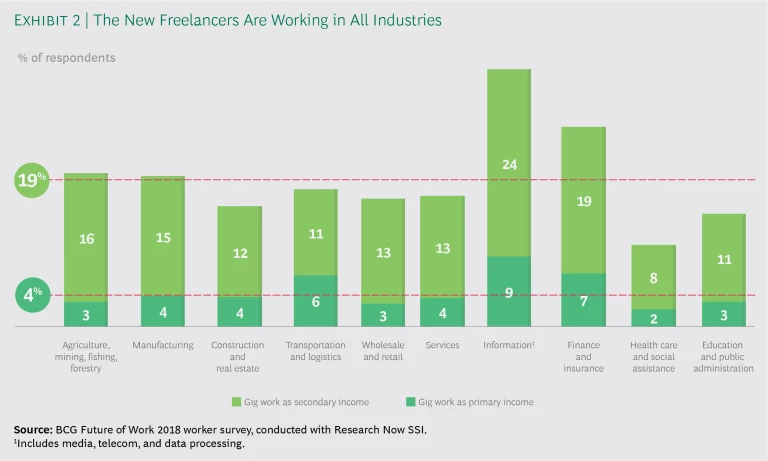

Public discourse on the sort of jobs that dominate the gig economy often focuses on on-demand chores in delivery and mobility services, such as Uber and Lyft. It’s time to reboot that conversation, our survey found. The new freelancers are active in all industries—including B2B and retail sales and education—not just in the traditional freelance strongholds of mobility, delivery, IT, and data processing. (See Exhibit 2.)

In short, digital freelancing has emerged as a significant source of primary and secondary employment in all major industries, giving virtually all companies access to new freelancers.

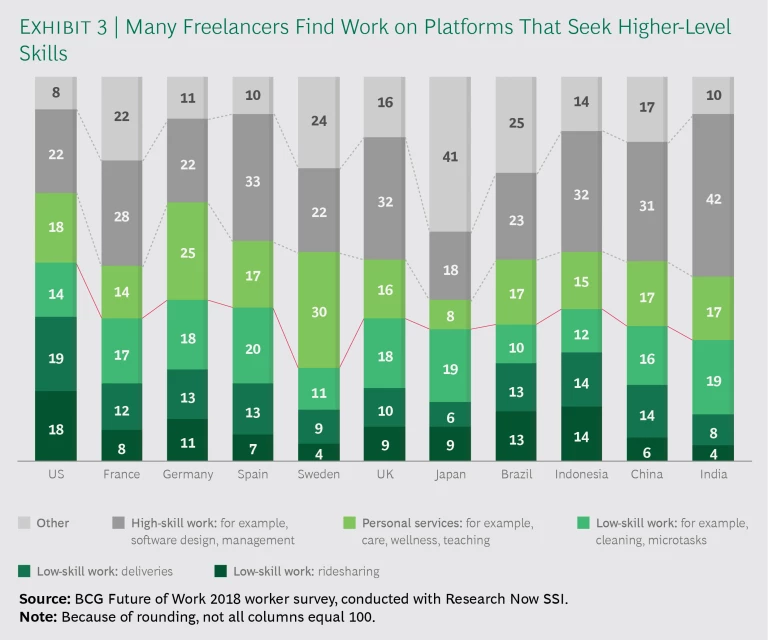

Our worker survey, as noted earlier, was designed to include a significant sample of less-educated, lower-paid workers. But the perception that the gig economy is dominated by poorly paid work—such as ridesharing, delivery, clickwork, and microtasks—also proved false. Low-skill, low-wage freelance tasks accounted for only about half of the freelance work sourced through platforms. Much of the remainder comprised higher-skill, higher-paid work, such as software development and design. (See Exhibit 3.)

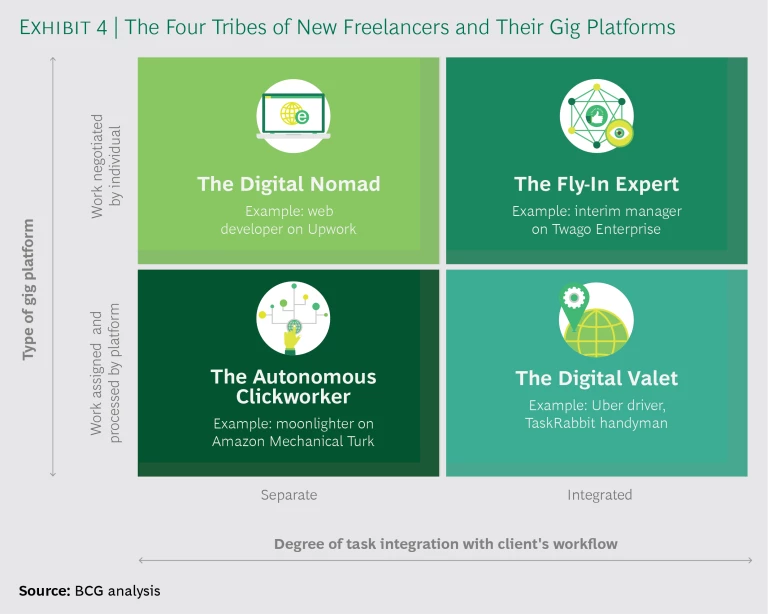

Gig platforms are not created equal. They differ in structure and in other meaningful ways, including the type of work offered, the type of freelancer seeking work, and the nature of the work contract. Platforms tend to be differentiated between those that own the employer relationship and assign and process work through the platform on the employer’s behalf, and those on which individual freelancers and employers negotiate terms.

The types and motivations of gig workers who use the various types of platforms differ accordingly. We have identified four “tribes” of new freelancers: Digital Nomads and Fly-In Experts, who negotiate individually, and Autonomous Clickworkers and Digital Valets, whose work is based on platform-set contracts. (See Exhibit 4.)

How Freelancers Really Feel About Gig Work

Contrary to widespread assumptions, most freelancers we surveyed said they do not choose gig work for lack of better options. Often they freelance in addition to other work or full-time employment. For many freelancers, gig platforms fulfil goals, preferences, and needs beyond compensation. Those benefits, they said, include greater autonomy and flexibility in their work and private lives and better choices of work projects.

Most freelancers we surveyed said they do not choose gig work for lack of better options.

For women, minorities, and workers in emerging markets who otherwise had few or no employment possibilities, platforms created or expanded their opportunities by making it possible for them to work remotely.

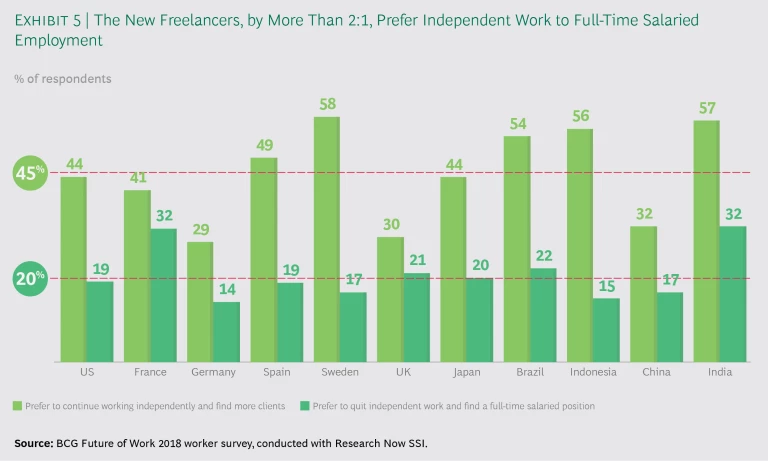

Freelancers typically find work through multiple types of platforms in addition to personal networks, and they generally work on several projects simultaneously or sequentially, as needed. When asked to define their preferred future employment, around 45% chose remaining independent and adding clients as needed to increase their income, compared with only around 20% who preferred finding a full-time salaried position. (See Exhibit 5.)

Globally and across all types of workers in our survey, more meaningful work ranked as a top priority, along with higher wages. The new freelancers were no exception. The three top benefits they cited were the opportunity to spend time on more meaningful and interesting tasks, to be self-employed, and to fit full-time work more flexibly around private needs.

As a result, they also reported higher happiness and satisfaction levels with their work than people in traditional full-time employment, despite the fact that they were more likely to work more than 45 or even 60 hours a week, and to earn slightly lower salaries. The latter was especially the case when freelancing was the primary source of income.

Freelancing Evolves from Cheap Labor to Top Talent

Corporations have historically contracted freelancers to reap the cost benefit of using lower-skilled and lower-cost workers to execute noncore processes. In highly regulated labor markets such as France and Germany, hiring a freelancer doesn’t entail providing the health care and pension benefits that salaried workers receive.

Freelancers have been a readily available and flexible resource to staff projects quickly, plug capacity gaps, and cover peak demand. Today, however, freelancers are increasingly tapped as a source of scarce talent and expertise by companies that need to adapt to shifting customer demands. Labor-sharing platforms provide rare skills that companies struggle to source on the traditional labor market of full-time employees.

Today, freelancers are increasingly tapped as a source of scarce talent and expertise by companies that need to adapt to shifting customer demands.

An executive at a leading European bank told us that hiring freelancers and other external workers is “no longer merely a cost solution to get through restructuring times; it is about bringing very specific skill sets to the organization.”

Another executive, in Germany, said he posted a full-time opening for a Java developer, offering a 20% pay premium and exceptional perks. He did not receive a single application in 18 months and was forced to hire a freelancer to complete the work.

Operators of labor-sharing platforms and workforce management service providers, pivoting to a new business opportunity, are targeting corporate clients with services that help them manage the shift to external freelance talent while retaining flexibility and work quality. (See “The Growing Business of Helping Companies Shift to Freelancers.”)

THE GROWING BUSINESS OF HELPING COMPANIES SHIFT TO FREELANCERS

THE GROWING BUSINESS OF HELPING COMPANIES SHIFT TO FREELANCERS

As companies bolster in-house talent pools with gig workers, a market of service providers has mushroomed to help them make the adjustment.

Among the providers are gig platform operators, who are targeting large corporations with offerings to reduce the friction that can arise as companies bring on workers unexperienced with internal workflows. One platform that has shifted to corporate services is twago. The company launched in 2009 as a marketplace for freelance work, matching designers and programmers with projects posted by small and midsize enterprises that lacked skills in-house.

Twago grew to become Europe’s largest freelance marketplace, with over 500,000 ready-to-work freelancers, before being acquired in 2016 by Randstad, the large Dutch temporary- work company. In 2018, with Randstad’s support, the company added a second solution: twago Talent Pool, which creates and manages bespoke gig labor platforms under the brands of its corporate clients.

Twago Talent Pool vets freelancers’ experience and work quality. It also helps manage the integration of freelancers into the work processes and procedures of client companies.

Within a year of launch, the new service offering had won a significant base of corporate clients, including ten Fortune 500 customers, the company reports. Clients represent diverse industries. Roughly 40%—the greatest single share—are medical device and pharma companies, followed by managed service providers, which are 20%. Electronics and life science companies each represent 10%.

The enterprise software giant SAP also stepped into the market in 2014, acquiring a market leader now known as SAP Fieldglass for a reported $1 billion. The company was founded in 1999, as it foresaw that enterprises would become increasingly reliant on nonpayroll workers and service providers. It offers a cloud-based solution for finding, engaging, and managing external workers and service providers.

Customers can now achieve “total workforce management” of external and internal workers by using SAP Fieldglass coupled with SAP Success- Factors, a cloud business that offers HR management services.

The shift in corporate strategy toward embracing gig workers—despite the disruption to the company and to individual workers—shows that companies overall are attempting to become more adaptive and resilient in a fast-changing business environment.

How Companies Can Adapt to the Freelance Future

The gig economy seems to be here to stay, first and foremost because it satisfies the needs of individual workers and companies. Tapping the talent and capabilities of the new freelancers will impose a learning curve on corporations. The motivations and aspirations of gig workers often differ significantly from those of traditional employees—and therefore from the experience of most corporate employers.

To make the most of the new freelancers, executives in traditional companies will need to adapt their management practices and strategies to attract people who don’t necessarily like large corporations and find ways to integrate them into their operations. Here are some steps companies can take to get up to speed in the gig economy.

Embrace gig work and labor-sharing platforms to increase your company’s flexibility. When it comes to sourcing scarce skills and talent, and responding to changing customer demands, these platforms can be valuable tools. Gig platforms already offer access to significant parts of the workforce in all industries.

Map the skills your organization has and those it lacks. Our client work in re-skilling has taught us that many companies lack the basic data needed to map current skills and a foresight function to determine future skill requirements. Those tools would enable leaders to source critical skills and determine where and why freelancers fit into the picture—for flexibility, speed, cost arbitration, or talent access.

As the European bank executive told us, “We need a map of skill sets, and a map of skills compatibility and transferability. Yet we probably don’t even have the CVs of all our employees.”

Define your freelance sourcing strategy. You can either tap into existing labor-sharing platforms and networks or build your own. When using existing networks, companies should be deliberate in choosing those affiliated with high-quality freelancers who know the company’s work processes and procedures.

Philips, the Dutch multinational technology company, is among companies that have created their own solution. Its platform, Philips Talent Pool, allows the company to address the dual challenge of maintaining a pool of freelancers familiar with the company and vetting the quality of their work.

Labor-sharing platforms, whether self-built or external, allow companies to cast a broader net for resources, specifically for scarce skills.

Don’t just hire freelancers—integrate them. To get the most out of freelancers—and make them want a return engagement—companies need to adopt new capabilities, support systems, and ways of working. The workers in traditional corporate environments we surveyed often resented the friction, variable quality, and need for re-work created by the use of freelancers. “I had to redo all the poor work the freelancer did,” was a typical complaint.

Truly integrating temporary workers so that they can perform at a high level requires the willingness and the flexibility to create more adaptable workflows and processes. Companies must clearly articulate the role of these workers and the purpose of integrating them to gain broad internal support from and alignment with other workers.

Take advantage of new gig-economy support services. Investments related to the gig economy are shifting from the financing of marketplaces toward the development of adjacent technologies. The latter include such services as invoice processing and insurance provision for freelancers, and the development of shared online and offline work spaces. These moves into adjacent systems aren’t limited to startups. Large multinationals are also taking part, and many are leading the way, as SAP’s acquisition of Fieldglass demonstrates.

Engage in the regulatory dialogue. Regulation of the gig work domain is evolving rapidly. New Zealand has banned on-call work, Ireland has changed its legal definition of self-employment, US courts deal with lawsuits by Uber employees arguing for employee status, a UK parliament inquiry has called gig work “freeloading on the welfare state,” and strikes by Dutch gig workers have forced the Dutch government to establish a taskforce to study the phenomenon. While all these responses were triggered by situations involving lower-skill gig workers, companies might find they also face constraints and resistance when they contract higher-skill workers.

The best way for companies to stay on top of evolving regulation is to remain engaged in dialogue with regulators, legislators, labor platform owners, and opinion leaders. They should also monitor regulatory developments and shifts in public opinion and perception.

Freelancers aren’t the only option for companies looking to source critical talent in a flexible way and create a more adaptive employment model. But they can be an important part of the puzzle. Despite the challenges facing freelancers in many countries, gig work offers clear benefits to those in the workforce who value flexibility and self-directed work.

Whether to villagers in remote areas, homemakers with restricted working hours, or disabled people lacking access to the regular job market, gig work offers a significant chance for meaningful employment. Companies that are thoughtful and diligent in attracting, compensating, and retaining freelancers—in addition to traditional employees—fulfil an important social role as employers. At the same time, they strengthen the social and talent fabric of their own organization.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.