The COVID-19 pandemic has delivered perhaps the greatest shocks to international trade since the Great Depression. Global trade in 2020 is projected to decline by 20% according to our baseline scenario for economic recovery, and it is not projected to regain its 2019 absolute level of $18 trillion until 2023. Only the most optimistic economic scenarios see trade returning to its previous level in 2021.

Regardless of when the top-line numbers fully recover, however, the global trade landscape will still look dramatically different as companies shift their focus from fighting the pandemic to winning the post-COVID-19 future . As it destabilizes economies, intensifies geopolitical frictions, and exposes the risks of current global manufacturing and supply networks, the pandemic is also likely to redraw the map of world trade.

As it destabilizes economies, intensifies geopolitical frictions, and exposes the risks of current global manufacturing and supply networks, the pandemic is also likely to redraw the map of world trade.

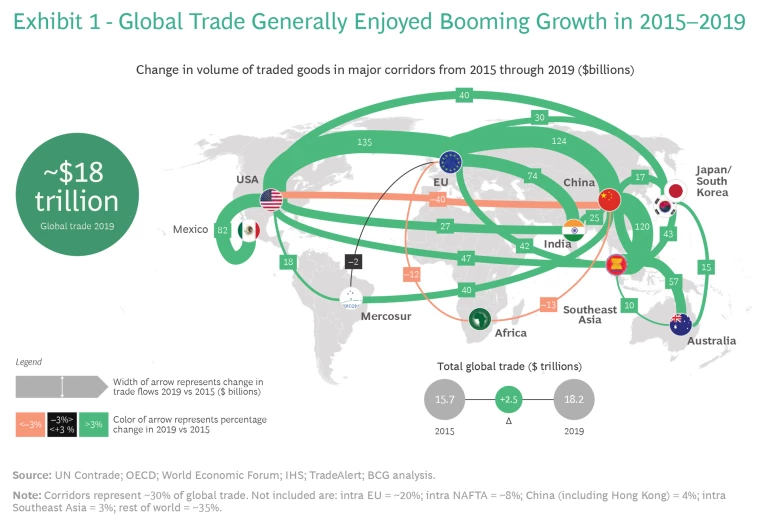

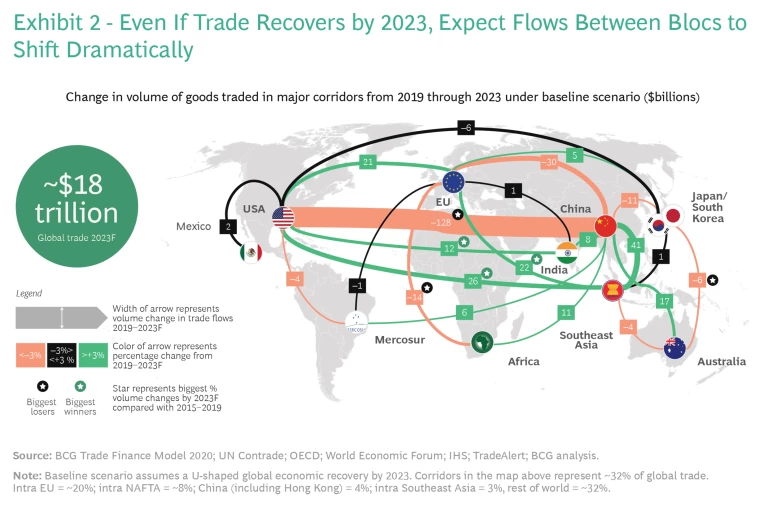

To visualize these shifts, we have prepared two maps depicting major trade corridors. One shows the actual change in trade volumes from 2015 through 2019; the other projects changes from 2019 through 2023 under our baseline economic scenario. (See Exhibits 1 and 2.)

Among the sharpest shifts:

- Two-way trade between the US and China in 2023 will have shrunk by around 15%, or about $128 billion, from 2019 levels. Trade between the US and the EU will continue to grow, but at a sharply lower rate than the $135 billion surge from 2015 through 2019.

- EU trade with China will have declined by about $30 billion from 2019 through 2023, after growing by $124 billion in the previous four-year period. EU trade with India and South America will flatten.

- Southeast Asia will continue to be one of the strongest gainers, increasing two-way trade by around $22 billion with the EU, $26 billion with the US, and $41 billion with China by the end of 2023, but still at a slower pace than the earlier four-year period.

Companies will be compelled to revise their mix of products and the design of their global supply chains—and governments their trade and economic policies—to adapt to these and other shifts. This will be particularly true in segments such as medical equipment, biopharmaceutical products, semiconductors, and consumer electronics, which are particularly exposed to geopolitical and macroeconomic pressures.

Other Ways COVID-19 Is Transforming Trade

The future of trade is also being redefined in other ways. For example, as part of its European Green Deal strategy to slash greenhouse gas emissions, the European Commission is considering pressing ahead with a proposal to impose a carbon tax on imports . This tax could redefine global competitiveness in a range of industries.

The pandemic is adding greater urgency as companies seek to make their manufacturing and procurement networks more resilient to shock.

The pandemic is adding greater urgency to efforts to restructure global supply chains as companies seek to make their manufacturing and procurement networks more resilient to shock. It is exacerbating the deteriorating US-China trade relationship, putting more than $500 billion in annual two-way trade at risk, especially in industries in both economies that will have a hard time replacing lost revenue and sources of critical components and materials. A potential decoupling of the US and Chinese technology sectors—which could make devices and IT systems in both markets no longer interoperable—might have even greater repercussions. These topics will be explored more deeply in upcoming Boston Consulting Group publications.

Companies should start acting now to adapt to the emerging new reality of the post-COVID-19 era, such as by reassessing their global manufacturing and supplier footprints and their approach to inventory, as many of the changes are structural and are likely to be long-lasting.

Forces That Are Redefining the Future of Trade

The realignment of the world trade order was already underway before COVID-19 hit in early 2020. For much of the post–World War II era, global trade had been a driver of global economic growth, expanding three times faster than global GDP from 1950 through 2008 in an era that saw fairly steady reductions in tariffs and new multilateral free-trade pacts. In the 2010s, however, trade growth flattened relative to global GDP growth as new and deeper multilateral trade deals stalled, the UK voted to leave the EU, and the US renegotiated existing trade treaties and relationships.

Tariff wars involving the US and major trade partners, particularly China, contributed to a significant shift in US import sources. US imports from China declined in nearly all major industry categories in 2019—most dramatically in energy products, semiconductors, machinery, and packaged foods—but rose in most sectors in trade with the EU, Japan/South Korea, India, Southeast Asia, and Turkey. The full effect of the US tariff hikes, moreover, was only partially felt in 2019. The COVID-19 crisis has been a further blow to trade. In addition to suffering from falling demand as nations sank into recession, trade was constrained by actions taken to control the virus, such as lockdowns of factories and controls on incoming shipments at ports, as well as by export bans on certain medical and agri-food products imposed by several governments and customs unions.

Going forward, global trade dynamics and the choices companies make regarding their supply chains will be significantly shaped in the following ways by the macroeconomic environment and geopolitical frictions, which will in turn influence supply chain tradeoffs.

The Macroeconomic Environment

The lower trade flows through 2023 predicted in our models can be attributed largely to decreased demand for traded goods as a result of deep recessions and structural economic damage. Low demand will, in turn, affect prices, particularly for commodities.

Trade volumes will be heavily influenced by whether economic recovery is shaped like a V, U, or L. Our projection that global trade will return to the 2019 level of $18 trillion in 2023 assumes that the global recovery path will resemble a U—after a steep decline, economic activity will remain low through at least 2020 and then rebound, presumably when some combination of mass testing, viable treatments, and an effective vaccine is available.

If recovery is rapid, resembling more of a V, trade could return to its 2018 level sooner than 2023. Under a slow, L-shaped recovery, international trade growth will remain relatively flat for several years. The shape and speed of recovery in specific countries will vary, depending largely on their progress in containing the pandemic.

Geopolitical Friction

The COVID-19 crisis has already accelerated the trend toward nationalist policies and managed trade. In addition to worsening the US-China relationship, the pandemic is prompting some governments and customs unions to place further controls on trade in medical and agricultural goods.

The COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the trend toward nationalist policies and managed trade.

By mid-April 2020, more than 80 countries had imposed export bans on medical devices and personal protective equipment needed to fight the spread of COVID-19. The Eurasian Economic Union, which includes Russia, banned certain agricultural staples, as did nations such as Vietnam and Cambodia.

Governments are also likely to put greater emphasis on domestic production to reduce the risk of future supply shocks, particularly of medical supplies and equipment. Germany has expressed interest in localizing more supply chains, for example, and South Korea is exploring measures to encourage reshoring of manufacturing.

Supply Chain Tradeoffs

For many companies, severe supply disruptions for everything from auto parts and consumer electronics to protective equipment during the pandemic have underscored the risks of concentrating too much production and sourcing in a handful of distant low-cost locations and overreliance on just-in-time inventory management. Rising tariffs, restrictions on market access, and other manifestations of geopolitical frictions will also require companies to alter their supply chains.

In our conversations with manufacturers across a range of sectors, executives are reporting a greater focus on supply-chain resilience. They are adopting more regional, “multilocal” sourcing and manufacturing footprints and are willing to maintain higher “safety stocks” in inventory—even if these moves entail somewhat higher costs. Companies are also more willing to put production in locations that are closer to customers—and are finding they can offset higher labor costs by adopting advanced Industry 4.0 manufacturing systems.

Companies should be thinking proactively about redesigning their supply chains to make them more resilient to future shocks. The types of change will vary by industrial sector and each company’s needs and strategic objectives, a topic we will explore in more depth in an upcoming publication.

The paths of the COVID-19 pandemic and the recovery of the global economy remain impossible to predict. But it is becoming increasingly clear that, by intensifying geopolitical and economic forces already at work, the pandemic’s disruptive impact on international trade will leave a lasting mark. Rather than waiting for a return to the status quo, companies should act now to make their manufacturing networks and supply chains more resilient. Companies should take a fresh, holistic view of the markets and trade relationships that are likely to drive growth and secure competitive advantage in the post-COVID-19 world.