Ten years after the 2008 global financial crisis, the profit margins of banks in advanced economies remain at historically low levels. The reason is simple: costs have been growing faster than revenues. Banks’ average return on equity has fallen to unsustainably low levels, especially in Europe.

Banks urgently need to act if they want to increase their profit margins. Because boosting revenue in the current environment will be difficult, banks must slash their costs. This will require simplifying offerings, digitizing operations, pursuing low-cost organic growth, and building scale through M&A and partnerships.

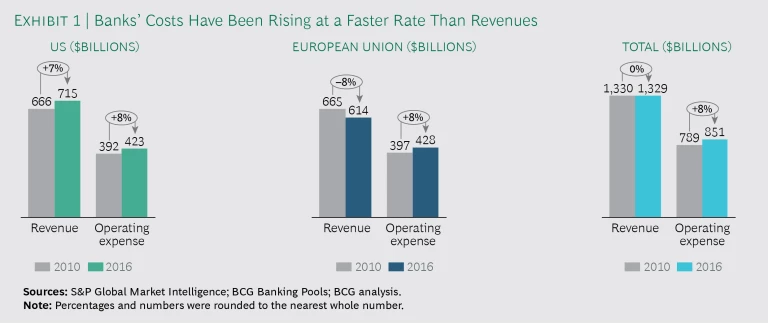

Costs Have Been Growing Faster Than Revenues

Banks have been digitizing their products, services, and processes over the past decade—a shift that was expected to reduce operating costs. Yet, from 2010 through 2016, banks in the US and the European Union saw costs increase by 8%, on average.

Banks’ rising costs can be attributed to three factors. The primary one is regulators’ response to the global financial crisis. Basel III, the Dodd-Frank Act, and a raft of other regulations increased not only the capital that banks must hold but also the resources that they must devote to complying with regulation. Although digitization has been helping banks shed low-paid branch and central-function staff, regulation has required them to add high-paid risk, legal, and compliance employees.

Banks’ rising costs can primarily be attributed to a raft of postcrisis regulations.

The second factor is banks’ significant investment in IT. To become a digital organization and to comply with new regulations, banks had to make major improvements to their IT systems.

The third factor is the fines and litigation costs that many banks—especially those in the US—have incurred as a result of the crisis. All told, the 8% average cost increase is no surprise.

While costs have been climbing, revenues have not kept pace. (See Exhibit 1.) Low interest rates have eliminated margins on deposits, and new competition from fintechs has constrained banks’ ability to compensate by increasing fees. Combined with increased postcrisis capital requirements, these cramped profit margins have resulted in average pretax returns on equity (ROEs) of 13% in the US and 6.2% in Europe, both of which are below hurdle rates.

Trends Are Unlikely to Change

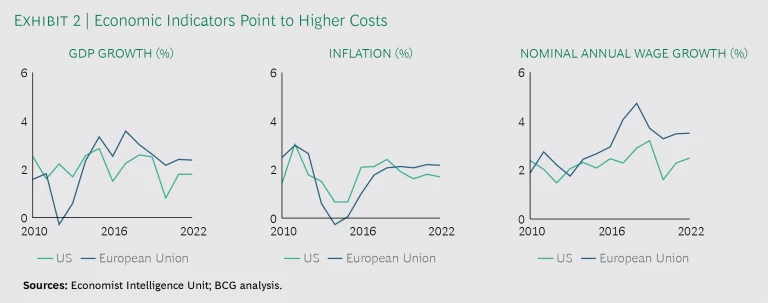

The trends of rising costs and constrained revenue growth are set to continue owing to several factors. Inflation is expected to be 2%, on average, in Europe and in the US through 2022; nominal annual wage growth is expected to run above its subdued postcrisis levels, at about 3%. (See Exhibit 2.) Hence, short of any structural changes, banks’ staffing and other costs are likely to continue rising in the coming years.

The regulatory trend is also not reversing (except, perhaps, in the US). A wave of new financial regulation in Europe—including the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II, the revised Payment Services Directive, and the General Data Protection Regulation—will increase the costs of compliance and require further technology upgrades.

At the same time, the prospects for increasing revenue are slim. In the near to medium term, interest rates are unlikely to rise much above present levels. The Federal Reserve is planning to hike interest rates during 2018 but only incrementally. And if the European Central Bank raises rates at all, the increase will be minimal. In addition, banks’ fee income will continue to be constrained by consumer protection regulations and competitive pressures. Considering banks’ continuing cost pressures and revenue prospects, their profitability isn’t set to improve anytime soon.

Banks Must Take Bold Steps

How can banks defy these cost and revenue trends to restore healthy profit margins and ROEs? Given how difficult it will be to increase revenue in the current environment, the real opportunities for improving margins lie in cost reduction.

Radically simplify products, services, and underlying processes. Because old products and services need not be eliminated when new ones are introduced, banks tend to build up large portfolios of closely related offerings. And most sell and support them through a wide variety of channels, with separate underlying processes.

This costly complexity is nothing new, but it is especially problematic now because it impedes digitization. Before banks can become digital institutions and realize the benefits, they must reduce the variety of products and services offered. Customers rarely miss those that are eliminated, because their functions are usually available in the remaining set of offerings.

Costly complexity is nothing new, but it is problematic now because it impedes digitization.

Focusing on a core set of products and services may seem contrary to the goal of using digital technology to personalize the customer experience. It isn’t. Personalization means offering a customer a product or service at the right time, in the right packaging, and through the right channel. Personalization is a matter of how products are delivered, not what those products are.

Banks should simplify not only the products and services they offer but also the processes by which products and services are sold and supported. Simplifying processes can deliver significant cost savings on its own, and it is an important step because it can help avoid the digitization of poorly designed and wasteful processes.

Digitize operations. Customers have high expectations when it comes to the speed and ease of doing business in the digital age. Some customers want to be able to visit a branch and be helped by a teller or advisor, while others want to bank online using mobile devices.

As banks work to meet customers’ expectations, fintech competitors are already succeeding at it. Initially focused on narrow lines of business, such as payments, fintechs are expanding into core product areas, such as savings and credit.

To avoid falling behind, banks need to digitize more functions and processes. The initial investment will drive up costs, but banks can halve the number of employees in back-office and support functions using technology that is already available, such as artificial intelligence and robotics. Indeed, given the direction in which these technologies are advancing, banks could aim to have a back office with no employees and realize spectacular operational cost savings.

Pursue low-cost organic growth. Banks worldwide have typically focused on increasing their market share, paying little heed to the cost of achieving it. As a result, they have often grown at the expense of profit margins. This approach is unsustainable, especially for incumbents in mature markets, where additional market share is likely to come with higher customer acquisition costs and reduced customer quality.

Banks have often grown at the expense of profit margins. This approach is unsustainable.

Banks must approach growth with a keen eye on cost. In most cases, this will mean building scalable platforms on which unit costs automatically fall as volume rises, the archetypical business model in the digital space.

Cutting costs is not a one-time job. Growth is the natural tendency of cost centers, such as the middle office, support functions, and IT. And this tendency is being reinforced by the growth of regulation. Keeping a path clear through a jungle is a never-ending job of hacking back the foliage that would otherwise overwhelm it. Controlling the growth of cost centers is a similarly endless job.

Use M&A and partnerships to build scale. Process automation is increasing the portion of banks’ costs that are fixed, as is the growing cost of complying with regulation and managing risk. Rising fixed costs, in turn, increases the importance of scale in banking and makes M&A and strategic partnerships attractive prospects for banks with limited opportunities for rapid organic growth.

We have already seen considerable consolidation since the 2008 global financial crisis. In Germany, for example, the number of credit institutions has declined by 12% since

Banking is a heavily regulated industry in which market entry and exit are highly constrained. That may normally be expected to protect the profit margins of incumbent players, but it won’t do so in the postcrisis environment. On the contrary, current regulations drive up costs and constrain pricing, while leaving banks exposed to fintech competition in some of their core lines of business.

Increasing revenue in the current interest rate environment will be difficult, especially in mature markets. To improve profit margins, banks must make bold moves to dramatically cut costs. If they do, banks can replace the recent trends with a virtuous circle, whereby the reinvestment of profits in technology continually improves efficiency. The currently unsustainable profit margins of most banks in Europe and the US can become a thing of the past for those with imagination, ambition, and application.