This article is part of a series from BCG and Hello Tomorrow on deep tech and its potential for businesses, governments, and societies around the world. It is based on the new report The Deep Tech Investment Paradox.

In 2020, many people suddenly became aware of humanity’s new capabilities for rapid innovation. The catalyst was the rapid release of coronavirus vaccines that harnessed a relatively new mRNA technology, developed by bioscientists around the world. But this technology does not stand alone. It is part of a broad-based wave of advanced innovation that is consolidating and amplifying breakthroughs from such diverse fields as materials science, quantum computing, synthetic biology, carbon capture, and even space technology.

This new wave, which we call deep tech, is still in its early stages. But it is expected to have an outsized impact.

Deep tech ventures are defined by their combination of visionary ambition, fundamental research, and commercial pragmatism. They address the most urgent challenges of our time and deliver financially viable outcomes along the way. The looming crisis of climate change, for example, has inspired a mix of new endeavors: small-scale nuclear fission and fusion, innovations in battery storage (which make renewable energy much more feasible), carbon-based materials (whose manufacturing process removes CO2 from the atmosphere), and methods for creating lab-grown meat. Housing and income inequality have sparked a wave of interest in modular home design and innovative building materials. The challenges of feeding a growing population and reducing the risks of agricultural chemicals have spawned a new farming industry that leverages synthetic biology. The need for finding alternatives to environmentally harmful plastics has led to a new wave of synthetic microbes, which can be managed to control and transform materials at the near-molecular level. Innovations in transportation technology, space travel, satellites, and precision farming all have similar potential impact.

It is not yet clear which new deep tech ventures are most likely to succeed, which investments will yield the greatest returns, or how rapidly their promise will be realized. But the field is already accelerating more quickly than many experts expected.

It is not yet clear which new deep tech ventures are most likely to succeed, which investments will yield the greatest returns, or how rapidly their promise will be realized. But the field is already accelerating more quickly than many experts expected. Early investments are generating remarkable results in both societal and financial terms, leading to a growing number of deep tech unicorns. Many successful ventures will follow in the next few years. And, as we explain in our new report, the field is catalyzing a new investment model—a contemporary counterpart to the investment models that underwrote previous industrial breakthroughs, such as electric power, the internal combustion engine, and the semiconductor.

Tech + Us: Monthly insights for harnessing the full potential of AI and tech.

THE DEEP TECH DIFFERENCE

Deep tech embodies a specific approach to creation, launch, and commercialization. Various enterprises have different names for this creative process, but all successful deep tech ventures share four basic attributes:

- They are problem oriented. Deep tech ventures aim to solve large and fundamental challenges to society. For example, 97% of deep tech ventures we have studied contribute to meeting at least one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

- They look at using the best existing or emerging technologies to solve the problem at hand. These solutions harness advanced materials, synthetic biology, artificial intelligence, or quantum technologies; 96% of deep tech ventures use at least two technologies, and 66% use more than one advanced technology. This enables them to generate distinctive intellectual property. About 70% of deep tech ventures own patents related to their products or services.

- They have shifted from digital innovation—based on bits—to digital and physical innovation—based on bits and atoms. About 83% of deep tech ventures are designing and building a physical product. Their digital proficiency is focused on using artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced computation to explore frontiers in physics, chemistry, and biology.

- They are catalyzing the emergence of a new cross-organizational ecosystem for investment, support, basic research, and application development. Because of the complexity and large scale of these innovations, and the deep scientific background that is needed to drive them, they involve large institutions and funding sources from the start. It is impossible for two entrepreneurial college dropouts in a garage to come up with a meaningful deep tech contribution on their own. An estimated 1,500 universities and research labs are involved in deep tech. [See “The Awakening of Funding Sources.”]

THE AWAKENING OF FUNDING SOURCES

- Generalist VC funds often have funding cycles that are too short to realize deep tech returns. Because the deep tech narrative is still emerging, these funds may lack a clear understanding of the field or its promise. They need better access to deep tech networks or to qualified experts who can help evaluate prospects. According to a recent survey conducted by BCG and Hello Tomorrow, 81% of deep tech entrepreneurs agree that “investors on average lack scientific or engineering expertise to assess deep tech potential.” Venture investors tend to rely on the power of distributed returns. They bet on large numbers of promising pitches, hoping that at least one in ten ventures will succeed with enough returns to compensate for the nine ventures that fail. This approach doesn’t work for deep tech, where significant resources are needed in the early years.

- Specialized deep tech funds, increasingly prevalent, understand this type of investment. But they have been limited in size. The average deep-tech-oriented venture capital or growth fund manages $105 million. By comparison, the average venture capital or growth fund manages about $148 million. Deep tech funds thus lack the scale to fully support the deep tech ventures they invest in, as well as the ability to create a partner ecosystem, particularly after the seed phase.

- Private equity funds tend to perceive deep tech investment as outside their remit and skill set. But they could be better suited to this investment than they may realize, and failure to move in this field carries risks for them. There was a similar failure to invest in digital during the early stages of its innovation wave, and many PE firms saw their assets ebb away. Deep tech has the potential to rewrite the rules—just as digital did. But, because of its focus on large and fundamental challenges, deep tech is likely to disrupt multiple industries with cross-sector upheaval.

- Limited partners (LPs), which include many sovereign wealth funds or family offices, tend to invest in established funds with solid reputations. These are conservative choices, supported by a comfortable network of fund managers with relationships developed over many years. This trend is reinforced by the growing buyout fund size, which rose, on average, from $700 million in 2015 to $1.6 billion in 2019. Despite these structural obstacles, some LPs may be drawn to deep tech on a broad scale. Sovereign wealth funds are frequently tasked with directing their funding toward strategic objectives, such as environmental or societal goals. Family offices are proven champions of patient capital, often investing over a 10- to 20-year cycle before exiting. Their investments would thrive in deep tech.

- Corporations, whose importance in the investment ecosystem has grown over the last five years, might seem like logical candidates to develop deep tech incubators, acquisition candidates, or joint ventures. But few corporate investors have the necessary internal R&D capabilities and flexibility. Our survey reaffirmed this view: 47% of deep tech ventures said that “corporations lack agility to work with deep tech ventures.” Moreover, corporate R&D activities are often focused on incremental development rather than major disruption. In many companies, the culture favors a “not invented here” attitude about fundamental innovation; ideas and offerings that come from any other group tend to be dismissed. As a result, businesses frequently wait until a venture is market proven, and thus pay a hefty valuation premium much of the time.

- Governments and institutional research funds have so far formed the backbone of deep tech investment. They play a crucial role as they did in previous innovation waves. Public sector organizations, universities, and large nonprofits have disbursed grants to early-stage ventures, often taking higher risks than their private sector counterparts. Public and university bodies also promote benign market conditions for deep tech in other ways. They may purchase or subsidize early-stage products, reducing price and cost; they may provide laboratories and other assets to help researchers; and they may act both as regulators and political facilitators for infrastructure and project finance, bringing together stakeholders such as banks, companies, municipalities, associations, and private investors. They can be most effective if they move beyond purely finance-oriented roles to form or join networks with researchers and engage with larger numbers of commercial participants, such as venture capitalists. The Engine, a venture fund spun out of MIT, observed that most US grant funding plans fail because governments do not have the same privileged access to entrepreneurs as VCs and cannot provide them with commercial opportunities.

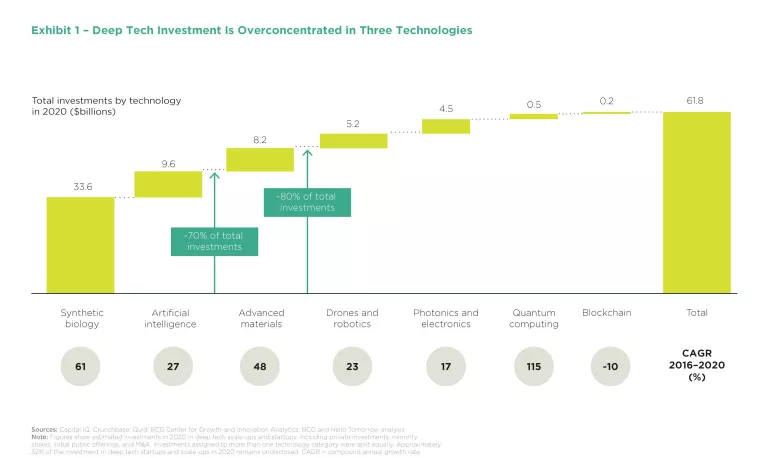

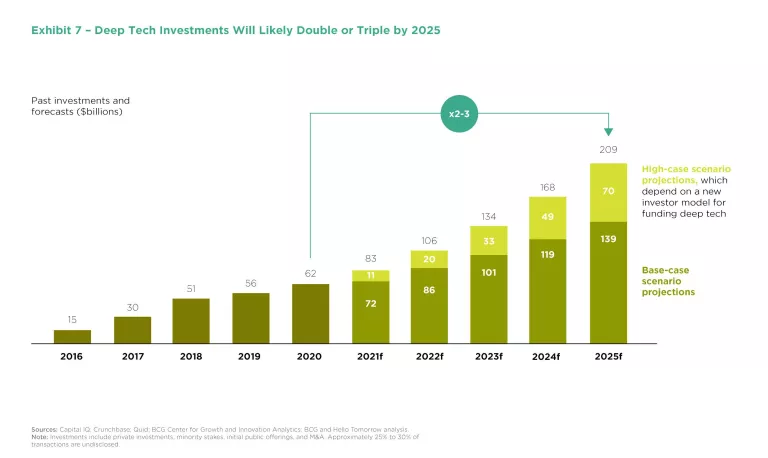

A few major investors are already profiting from their involvement with deep tech; others are profoundly excited by the possibilities. The amount of capital put into deep tech has grown fourfold, from $15 billion in 2016 to more than $60 billion in 2020. But by and large, the global investment community has not yet taken up this opportunity. Deep tech is still considered a niche investment, and it has developed in a skewed and patchy fashion. Paradoxically, investment “dry powder” (investment capital seeking relatively high returns) stands at record levels. In other words, an estimated $1.9 trillion in PE, VC, and growth capital is seeking higher equity returns beyond near-zero-interest-rate bonds.

Even within the field, many opportunities are overlooked. Investment in AI and synthetic biology attracted two-thirds of deep tech investment last year, leaving just one-third to be spread across the remaining universe of heterogenous startups. (See Exhibit 1.) The deep tech investment landscape is also geographically concentrated, with the US comprising almost 75%. Promising ventures in Europe, China, and the rest of the world are significantly underfunded.

As a result, investors are missing an opportunity to participate in a significant new wave of innovation. They are also making themselves vulnerable to competitors that move more quickly or incisively. Deep tech enterprises, meanwhile, are losing access to capital that would help them grow in line with their ambitions. And the rest of us are losing out on the benefits of these innovations. Deep tech endeavors are, for example, mitigating the effects of global climate change.

How can deep tech and investment capital resolve their differences and join forces?

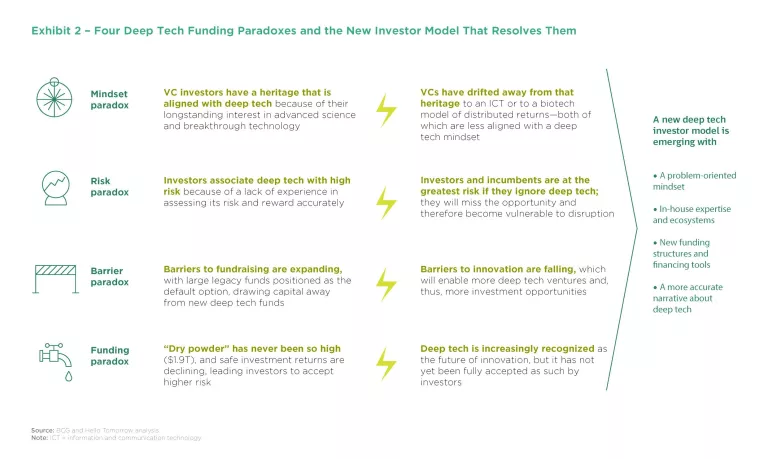

By resolving the four paradoxes that hold them back. (See Exhibit 2.) The first has to do with the mindset of investors, who are less familiar with advanced science and breakthrough technology than many people expect them to be, especially considering the heritage of venture capital. The second involves risk and opportunity; deep tech is seen as a high-risk investment, but the greatest risks, as with many disruptive innovations, may come from ignoring it. The third reflects the contradictory nature of barriers in this field: barriers to fundraising are expanding, while barriers to innovation are falling. Finally, the fourth paradox recognizes that potential funding for deep tech is unprecedentedly large, but it has not yet found its connection to this field.

Resolving these paradoxes will require investors to think differently about deep tech. There is also a challenge for venture leaders, who must look beyond universities and governments as potential funding sources to form true ecosystems with nonprofits, venture capital, and private sector participants. Ultimately, the investment community has every reason to act. As was the case with mRNA vaccines, opportunities await to address social issues and to participate in the innovations that will shape the future of civilization.

PARADOX 1: THE MINDSET OF THE PAST IS BETTER FOR THE FUTURE

The economist and venture capitalist William Janeway, author of Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy, has pointed out that frontier innovation funds should ideally be led by contrarian investors—meaning those who invest “against the current mood of the market.” To fund deep tech in the future, we need to adapt the investment mindset of the past.

In the 1960s and 1970s, as the current wave of digital technology started to emerge, angel investors and venture capital firms took long-term positions in the companies they funded. This was needed to bring breakthrough technologies (such as semiconductors, personal computers, communications devices, and software) to a mature stage of development. Many VC firms made enviable reputations this way as leaders in an expanding field.

But the general mindset of many investment firms has shifted since then. Today, such firms tend to rely on the power of distributed returns. Since they don’t risk very much capital early in any single investment, they end up with moderate positions in multiple ventures, and then double down to support the ventures that yield rapid results. The result is often incremental investing on well-travelled paths.

This approach doesn’t work for deep tech, for which significant resources are needed in the early years. Many investors are open to innovation in the abstract, but in practice they seem to be reluctant to commit themselves to those breakthrough ventures that will make the most difference going forward.

To be sure, deep tech ventures can seem unfamiliar. They could be funded publicly or through grants, located in academic or research facilities without the trappings or network of a typical digital startup. Instead of being led by a close-knit group of entrepreneurs who all went to college together, the projects may be led by postdoctoral scientists, with colleagues across the world participating.

Investors can succeed in deep tech by going back to their historical roots, making a more focused commitment to their investments and remaining concentrated on the problems they address.

Investors can succeed in deep tech by going back to their historical roots, making a more focused commitment to their investments and remaining concentrated on the problems they address. To adopt the right mindset for deep tech, investors need to embrace a problem-solving orientation: a willingness to help address issues with a company rather than moving on to something else. They should also actively build their portfolios around urgent and fundamental issues: the problems that society needs to solve. These challenges are broad enough that ecosystems (with coinvestors, universities, public authorities, and corporate groups) can form to address them. IndieBio Founder Arvind Gupta stated it very clearly: “I invest in problems, not in solutions.”

Some deep tech deals are starting to experience competition, but investors shouldn’t passively wait for deal flow. They should actively seek and select ventures. The result will be a more focused portfolio of projects with clearly identified problems and strong magnetic pull, capable of attracting other resources and collaborators. The investors can then commit their attention and financial resources wholeheartedly, helping manage challenges as they arise—recognizing that in deep tech, even more than in other fields, necessity is the mother of innovation.

PARADOX 2: NOT ACTING IS RISKIER THAN ACTING

Of all the concerns investors raise about deep tech, the most frequently voiced have to do with risks and the vulnerability of their position.

In one sense, these concerns may be justified. Compared with a purely digital venture, like a software-as-a-service (SaaS) offering or platform, a deep tech venture has a higher barrier to entry. It has a longer runway to market, a higher initial investment cost, and fewer successful companies in the field to point to. Investors also associate deep tech with high risk because they have not developed the experience and practical knowledge needed to accurately assess a company’s potential.

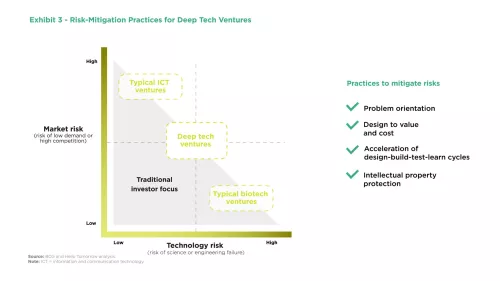

But when you look more closely and understand risk-mitigation practices, deep tech opportunities tend to be less risky than their purely digital counterparts. When tackling a fundamental problem, often unaddressed for decades, the demand will be there. The risks, then, have to do with engineering execution and the business model, with the question being: “Can we produce this at an affordable, scalable price?” Investors are less attracted because they have not been exposed to these types of issues; they are less well-versed in the technologies and problems that deep tech addresses.

The riskiest move is avoiding deep tech, for the same reason that avoiding digital investments was risky in the late 1990s and early 2000s. At that time, many investors still felt digital ventures were unfamiliar, and the bursting of the internet stock bubble in 2000 made investors even more leery. But it was at that moment that several of today’s dominant digital companies really began to take off. The funders who prospered the most were those who got started early, persevered, built their networks, and took the trouble to learn about the industry.

Similarly, investors who stake out an early position in the deep tech space will be able to seize fast-growing opportunities and will be better prepared as deep tech investments become more attractive in the future. Incumbent companies, particularly in industries like energy, chemicals, and agriculture, will probably be disrupted by deep tech if they don’t climb aboard. Deep tech advances cross the boundaries between science, engineering, and design. They are here to stay. Ignoring them won’t stop them from challenging the status quo or taking down market leaders, just as similar advances have done in the past.

According to a survey by BCG and Hello Tomorrow, 69% of deep tech investors disagree with the idea that market risks, as well as those risks associated with science and technology, are “too high.” This can be explained in part by their own hard-won access to expertise: to assess deep tech potential, 79% of investors made use of external experts, 42% hired their own PhDs, and 37% hired graduate-level-science-degree holders or engineers. They also regularly consult with other investors (seeking coinvestment), with corporate leaders (often proposing collaborative ventures at a higher scale), regulatory institutions, and universities. The whole deep tech ecosystem needs to be activated and amplified—and more investors brought on board—to support ventures along the journey.

There are now efficient practices to mitigate risks further, which investors should master to best help deep tech ventures avoid market failure and technological overreach. (See Exhibit 3.) For example, the acceleration of a cyclical design-build-test-learn (DBTL) approach, borrowed from lean startup methodology, allows teams to continuously improve and test faster, even in highly original research and development efforts. This gives deep tech ventures the ability to introduce minimum viable products (MVPs). Synthetic biology companies, for example, have reduced their time-to-release cycles from months to weeks.

Once developed in the lab, the deep tech solution is also typically protected as intellectual property, which allows it to scale rapidly while limiting competitors.

Finally, risk is lessened by considering value and costs at every stage, from inception through the manufacturing launch. This may seem counterintuitive to some because it frontloads the cost analysis into the design phase. But it allows the entire operation to focus on customer value. SILA Nanotechnologies, for example, developed new battery technology that scaled efficiently by using globally available components and bulk synthesis reactors. They started in the cellphone battery segment, where value was the highest, before expanding to others.

PARADOX 3: BARRIERS ARE RISING AND FALLING

Financing shortfalls represent a concern because the initial costs of deep tech research and development can be steep. No one can deliver a hybrid electric jet engine or nuclear waste disposal solution on a shoestring. Because the most critical technological risks and design-to-value practices are frontloaded into the early stages of reaching an MVP, early investment rounds (typically seed, first, and second rounds) appear daunting.

Yet the barriers to deep tech innovation are falling. R&D costs in gene sequencing, prototyping, and simulation are a fraction of what they were a decade ago. In infrastructure, progressive descaling allows for a faster time to market due to smaller plant set-up costs, progressive capital deployment, and optimized maintenance efficiency. Examples include Seaborg Technologies’ floating nuclear power plants or Desktop Metal’s local additive manufacturing systems. Development time is also shrinking fast: the ETA for the quantum computer continues to be reduced. And DeepMind’s AlphaFold 2, a highly visible project, solved the 50-year-old 3D protein-folding challenge far earlier than most observers expected. During the next few years, as costs fall (some faster than others) and companies grow in size and scale, more capital is likely to become available for deep tech investment.

In parallel, the barriers to entry for investors raising deep tech funds are getting higher. Much of the large-capital investment needed by deep tech is bound up in the kind of sizeable legacy funds with solid reputations that are preferred by limited partners (LPs). It is therefore unavailable to deep tech ventures in their later rounds.

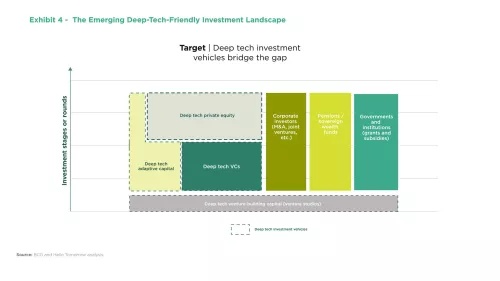

This structural factor may be temporary. A group of deep tech investment vehicles is emerging. The relatively static and empty investment landscape looks likely to evolve into a more active and dynamic ecosystem. (See Exhibit 4.) Deep tech VC and PE funds, as well as long-term adaptive capital and venture studios, will help consolidate the ecosystem and better support deep tech ventures along the investment journey. More specifically, deep tech VC funds would be distinguished by their 10- to 15-year lifetimes and their fund sizes of $150 million to $300 million. They would be supported by selected anchor investors, their cross-cultural and multidisciplinary teams, research-and-publication engines, and wide networks (such as universities, corporations, or government agencies). All of this would take the fund back to the original core VC concept: an ambitious vision focused on transformational businesses.

Fundraising barriers of investors will be lowered by different mechanisms that enable longer timelines—such as rolling funds, opportunity funds, or the growth of the secondary market—providing easier exits for investors. Lastly, diversified tools beyond traditional equity, such as revenue-based financing, carbon credits, or venture debt unlocked by the first commercial revenues, can help overcome the financing barriers of deep tech ventures.

PARADOX 4: THERE’S PLENTY OF AVAILABLE CAPITAL BUT LIMITED INVESTOR MOMENTUM

Today, record amounts of capital ($1.9 trillion) are chasing returns, but there are fewer profitable safe havens than in the past. Bonds and relatively risk-free equities are delivering low returns and driving investors away. The latest symptom of urgency caused by this growing pool of capital is the boom in special-purpose acquisition companies.

Deep tech investment opportunities may be called on to fill the gap. With some adjustments to funding models and appropriate risk-mitigation strategies, these types of investments could be added to more investor portfolios.

But deep tech ventures still have a hard time raising capital. As one survey respondent put it, “The biggest challenge we face is being able to tell a story about what the tech means.” A pitch isn’t a thesis, and many deep tech scientists don’t understand the grammar of venture capital. They underplay successes, focusing on evidence-based certainty; they often elaborate on the complex scientific and technical features of their ventures rather than the end applications and business potential.

“There are three big myths,” says Dakin Sloss, founder of Prime Movers Lab: “That deep tech takes longer, that it’s more capital-intensive, and that it’s higher risk.” Debunking these myths requires reframing and articulating the deep tech narrative, which will spread across the whole investment chain, from ventures to VC and PE funds. The funds themselves should also develop a narrative for LPs, an underestimated leverage point in the investment system.

This narrative should feature at least three core messages.

- Risks are high, but they can be mitigated. This can be accomplished through problem orientation, design-to-value and design-to-cost practices, acceleration of DBTL cycles, and defensible IP.

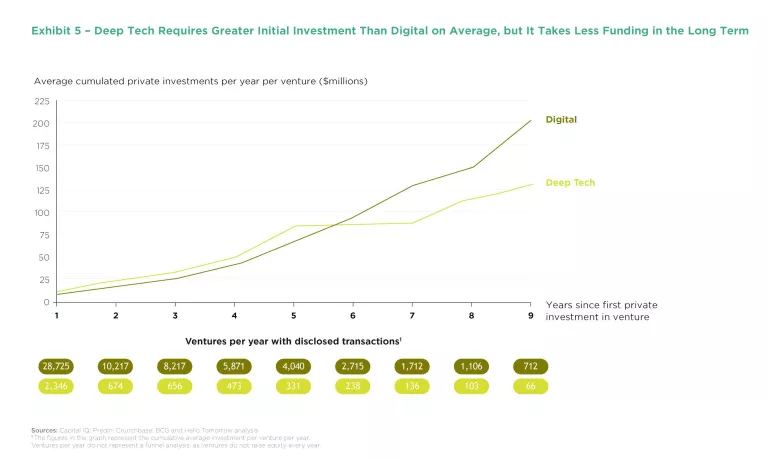

- Early equity needs are higher on average but can be controlled over time. The investment timeline and overall equity needs must be put into perspective. Deep tech ventures do, on average, initially require higher equity funding. But the costs can remain relatively controlled—especially compared with digital and SaaS ventures, for which costs continue to rise when companies acquire customers or outcompete rivals. Once deep tech ventures reach their first commercial revenues, they can switch to nondilutive funding and project finance. (See Exhibit 5.)

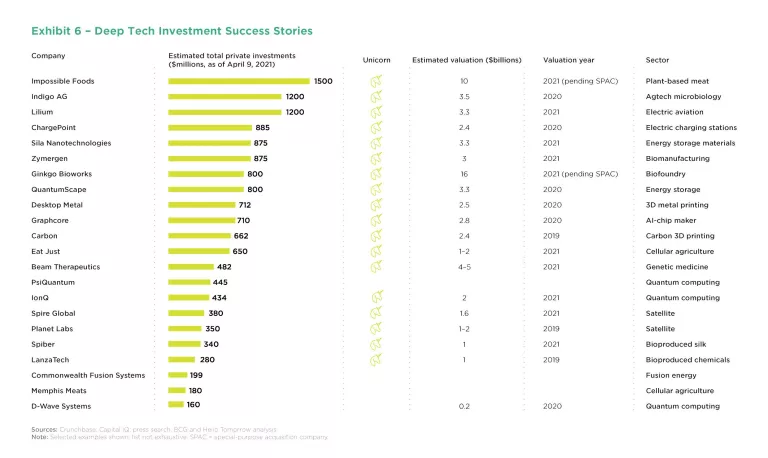

- Deep tech already has an impressive track record. Perhaps most important, the success stories in deep tech aren’t being shared. (See Exhibit 6.) The question isn’t about generating a track record; it’s about spreading it. While much attention has been focused on discovering the next Uber or Deliveroo, hundreds of millions of dollars in smart money have recently been pouring into deep tech (typically without much attention), quietly creating unicorns and leading to successful corporate and IPO exits. For example, according to Fifty Years, a VC firm, deep tech companies have increased the equity value of their portfolios by $3 billion or more, with at least eight companies enjoying valuations over $100 million.

ESTIMATING THE DEEP TECH OPPORTUNITY

Deep tech investment has reached a pivotal moment. Valuations are affordable relative to their potential upside, particularly outside the US, as deep tech has not climbed the hype curve of the unicorn-heavy digital space. This creates big opportunities for venture capital and first-investor advantages, considering the affordable valuations and speed at which the wave is rising.

We estimate that if current trends continue, deep tech investments will grow to about $140 billion by 2025. But if the new investment model and ecosystem mentioned here are established—including a new narrative for investors, new opportunities for investors and deep tech entrepreneurs, an ecosystem of enterprises and investors, more-advanced funding structures, better risk-mitigation practices, and a mindset more friendly to deep tech—we estimate that investments could surpass $200 billion by 2025. (See Exhibit 7.)

Humanity is approaching an epochal shift. Deep tech can propel society to a new dimension of bits-and-atom solutions. This field is just emerging, and no one quite knows the scale and shape of the wave about to strike. But it is imminent. We have a financial and moral imperative to remove the frictions in the investment chain, mitigate the risks, and unlock the power of deep tech.