Every company seeks to pursue its strategy with the lowest possible level of asset ownership, but determining the optimal level is challenging. Executives face a tough dilemma when considering asset weight. Asset-heavy, vertically integrated models offer superior control, but they tie up significant capital and frequently prove less flexible in a fast-changing environment. By contrast, asset-light business models confer greater flexibility, but it can be tough to manage them, and the risk of leaking intellectual property (IP) or becoming less valuable is greater.

Both integrated and asset-light models—when well chosen—can deliver good results. For example, Zara, a Spanish fashion retailer, benefits richly from its integrated model. It designs and manufactures its lines of fashion apparel in its own facilities and sells them through its global network of company-owned stores. Nike, on the other hand, also delivers superior results with its athletic apparel at a significantly lower level of vertical integration.

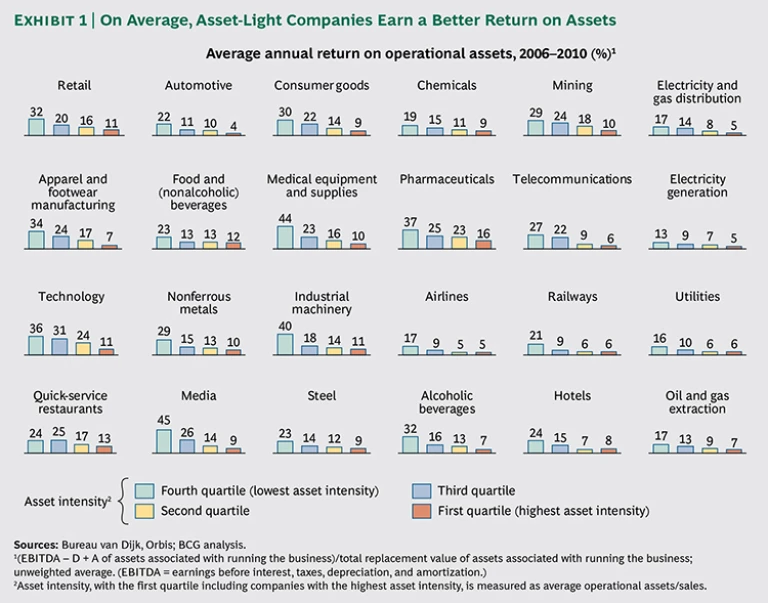

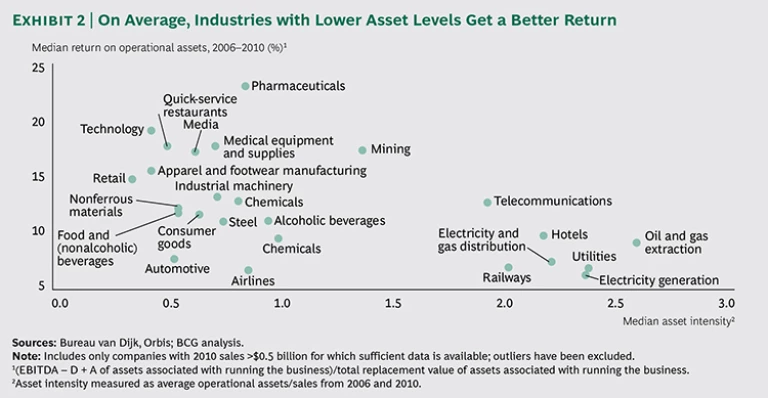

But focusing on individual examples obscures a deeper truth. We analyzed 2,687 of the largest companies—across 24 industry sectors—that publish financial results. Our analysis revealed that on certain measures, the more asset-light companies on average earned greater returns on assets than their peers did. (See Exhibit 1.) This finding also holds across industries. Industries that have lower levels of assets generate a better return on the assets they hold. (See Exhibit 2.)

While “light” is not always the right choice—and sometimes is absolutely the wrong choice—its applicability is growing. Our research has identified new management approaches—which we call smart-control techniques—that leading companies are using to break the compromise between integrated and asset-light models, enabling companies to do more with reduced asset levels while retaining appropriate control.

The Benefits of Going Light

Asset-light models can deliver a better return on assets, lower profit volatility, greater flexibility, and higher scale-driven cost savings than asset-heavy models. Let’s look at these benefits more closely.

Better Return on Assets. Our analysis revealed that although asset-light companies on average have lower margins (one way or another, they must “pay rent” on the assets they use but don’t own), these are usually more than offset by the benefits of lower asset weight (defined as the ratio of the company’s undepreciated operating assets to its annual sales). In fact, in every sector we analyzed, the more asset-light companies on average earned greater returns on their assets than did their peers. Although this benefit reduces the price-to-earnings ratio in some industries, the fact remains that the ratio of price (market value of equity) to operating assets is better for asset-light companies than for their peers in almost every sector.

This dynamic played out dramatically in the hotel sector in the first decade of this century. At that time, hotel chains reduced their asset ownership, selling most of their properties and, in many cases, using the capital released to expand into developing economies, where room demand was projected to grow far faster than in developed markets. The five largest hotel chains’ ownership of assets is now about one-third lower per revenue dollar than it was in 2002.

For hotels and other companies seeking to shed fixed assets such as real estate, a simple sell-and-lease-back contract does not do the trick: the fixed rent is considered a long-term liability. A better option is to negotiate a variable rent, which is typically based on a percentage of earnings, revenues, or some other predetermined factor. For example, from 2005 through 2010, the Accor hotel group sold €4 billion in properties, for which it pays rent that is based on a percentage of hotel revenues. Using a franchise model or a long-term management contract in which the local hotel owner pays a branded hotel chain to manage the hotel also gets assets off the balance sheet. Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, for example, uses both of these models.

Lower Profit Volatility. Companies with high fixed costs rely on revenues to cover those costs, so net income depends on utilization—and profits can swing widely from one year to the next. By contrast, asset-light companies’ costs are more variable relative to their revenues, so profits are less volatile. This dynamic is seen in a wide range of industries, including oil and gas extraction, utilities, electricity and gas distribution, media, technology, industrial machinery, chemicals, mining, retail, food and (nonalcoholic) beverages, and consumer goods. This volatility-smoothing effect is not felt in industries in which most costs are variable (such as apparel and footwear manufacturing) or when asset-light models do not involve variable rents (such as railways). The key is to go asset light in a way that ensures a high proportion of variable costs.

Greater Flexibility. Companies with lower levels of asset ownership are able to respond faster to changing demand, technology advancements, new market opportunities, and supply chain disruptions. For instance, Li & Fung provides supply-chain-management services to clothing manufacturers and other businesses with high-volume sales of time-sensitive consumer goods. The company provides and coordinates supplier, manufacturing, and shipping services for its customers without actually owning any of those capabilities itself. During the 2003 outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong, the company was able to spread its manufacturing orders across several factories in mainland China, offsetting the risk that one or more of them might need to close. As a result of this and other actions, Li & Fung lost only 5 percent of its orders. And because asset-light companies rely less on legacy assets, they’re also able to respond faster to new market conditions and changes in technology.

Higher Scale-Driven Cost Savings. Asset-light models can help companies achieve scale without having to invest capital. For instance, the production of semiconductors typically requires multibillion-dollar capital investments, which very few companies have the scale to justify. Intel owns its own fabrication plants, but Apple takes the asset-light route, buying many of its chips from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, as do many smaller companies that aim to minimize the amount of capital tied up in fixed assets.

Being asset light can also help large companies avoid the diseconomies of scale that arise from owning many small shops in many locations. For instance, it is far more efficient for a mobile-phone company to franchise its smaller retail outlets than to operate thousands of small stores. An added benefit: franchisees run the stores as owners, not employees, so they have a stake in the business and are highly motivated to succeed.

Common Asset-Light Models

Although there are many asset-light models, some of the most common are outsourcing, asset sharing, licensing in, and licensing out. (See “Nine Asset-Light Business Models.”)

NINE ASSET-LIGHT BUSINESS MODELS

We’ve identified nine asset-light business models: outsourcing, pay per use, marketplace, licensing in, rebranding, asset sharing, franchising, licensing out, and product-to-service transitions. (See the exhibit below.) Six are upstream models in which the asset-light company relies on other companies to provide critical inputs. The other three are downstream models in which the company uses an asset-light model to expand the reach of its products or services. Of the six upstream models, all but asset sharing are variants of outsourcing.

Outsourcing involves buying products or services from external providers instead of producing them in-house. Widely used in the manufacturing industry, the model works best when the IP involved is either protected (through patents and a willingness to litigate) or is not a source of differentiation. For example, Vizio became the U.S. market leader in LCD TVs after realizing that LCD panels were not themselves a source of differentiation. The company was able to keep costs low by buying the panels from multiple sources and taking advantage of temporary surpluses.

In the asset-sharing model, two or more companies share the cost of expensive assets if utilization is the key to returns. In some asset-sharing situations in which investors want to diversify their risk, companies share the cost of risky assets, such as oil and gas fields that can be expensive to develop and may come up short. Partners that enter into asset-sharing arrangements can be in the same or different industries. For instance, Cathay Pacific and DHL share aircraft to provide combined passenger-and-cargo flights. Even competitors can share assets that aren’t strategically differentiating. For instance, Hulu’s TV-streaming platform is owned by NBCUniversal, Fox, and Disney/ABC Television Group—all of which benefit from the networking effects of Hulu’s larger audience.

Licensing in allows companies to bring in and commercialize products developed by outside partners. Pharmaceutical companies often take this approach to reduce R&D costs. The flip side of licensing in is licensing out, through which a company licenses the use of its product to a partner, sometimes in another industry. Licensing in and licensing out are typically used at the start or end of a brand’s life cycle. The fashion industry licenses out extensively—especially in the luxury segment. This can be an effective way to extend a brand into new markets without making a major capital investment. For instance, Armani Hotels & Resorts licensed its brand to Dubai-based Emaar Properties in 2004 as a way to participate in the luxury hotel market without actually buying properties.

When Light Isn’t Right

Despite the benefits that an asset-light model can deliver, sometimes a vertically integrated model is a better choice. When coordination, speed, know-how, or knowledge sharing is essential—or when core strategic assets, such as vineyards in the Champagne region, are scarce—greater integration can be helpful. (See “Is the Asset-Light Model Right for Your Company?”) Integration can also help ensure that the economic interests of all parties are aligned.

IS THE ASSET-LIGHT MODEL RIGHT FOR YOUR COMPANY?

To determine whether your company should hold on to its assets or adopt an asset-light model, you’ll need to answer two questions.

Is the asset strategic? Conventional wisdom says that if particular assets are integral to your company’s competitive position—for example, research or design labs that generate know-how—ownership is usually the best option. Still, the risks associated with offloading such assets can be offset by using smart-control techniques, particularly in conjunction with a franchising, asset-sharing, marketplace, or licensing model.

Is the asset in short supply? It is, in certain cases, wise to own scarce physical assets, such as premium hotels, installed power stations, or vineyards in France’s Champagne region. But when demand, supply, and investor appetite for such assets are variable, a pay-per-use model may create more value.

Zara relies on an integrated design, manufacturing, and distribution process to give it the flexibility to respond to changing fashion trends. This business model enables it to act faster and more decisively than its rivals, yielding both fewer stockouts and fewer markdowns.

A number of companies have tried to become asset light but have encountered problems in, for example, coordinating suppliers and maintaining critical know-how. Aligning economic incentives with suppliers is another challenge, as Lego found when it outsourced the manufacturing of its high-margin toy products to Flextronics in 2005. Lego needed high-quality products in quantities that could not be predicted far in advance. This need conflicted with the incentives it was offering Flextronics to keep costs low. Lego ended the partnership in 2008.

In later stages of the business life cycle-when profitable growth is waning-reintegration can be a winning strategy. For instance, yogurt maker Yoplait owned its factories in France, but it took an asset-light approach to international expansion, establishing franchises in 70 countries. Seeking further growth, the company opted for a strategy of vertical integration and began adding production facilities, beginning with a plant in Sweden in 2006 and subsequently acquiring its own franchisors in critical markets. This strategy proved a good way for Yoplait to grow its top line and increase brand control while remaining in its core business.

Getting the Best of Both Worlds with Smart Control

In our experience, companies can go asset light and still retain the benefits of vertical integration by improving coordination and knowledge sharing with their partner organizations. This smart-control approach involves six management techniques.

- Embedding or Colocating People in Partner Organizations. This provides an opportunity to model effective behaviors, offer formal and informal management advice, and check compliance with corporate policies.

- Duplicating Some Partner Activities. Duplicating some of the activities that partners perform—for example, having your own stores alongside the franchised outlets or your own production line alongside those of your partner—is an effective way to set pricing expectations, test new sales strategies, and demonstrate the correct way to manufacture, sell, or provide a service.

- Controlling Inputs. Some companies ensure quality by providing the raw materials and other inputs that suppliers or contractors use. Pharmaceutical companies typically own the patents on the drugs they outsource for production. Moreover, some companies also supply the active ingredients to the factory. Franchisors can control prime locations by owning the land that franchisees use, giving them an edge if the relationship deteriorates.

- Controlling Outputs. Companies must carefully manage their reputation and brand when they outsource aspects of their business. To this end, most franchisors, maintaining control of their downstream partners, restrict the use of the company brands, signage, and logos. Although price minimums are generally illegal, companies can print recommended prices on product packaging or indicate that an item is part of a multipack and not for individual sale.

- Controlling Systems. Maintaining control of processes and systems is another way to manage outsourcing and partner relationships. Restaurants typically control the inventory, ordering, and point-of-sale systems that franchisees use. Oil companies require contractors to follow specific project-management processes. Many companies maintain final-veto rights when they work with contractors or jointly develop products.

- Establishing True Win-Win Relationships with Critical Partners. Many companies give lip service to the concept of the win-win relationship without truly committing to it. The reality is that integrated models can prosper by treating all suppliers as expendable and interchangeable. By contrast, asset-light models demand greater reciprocity in at least the most critical supplier partnerships. After all, the success of the asset-light model depends on the health of the supplier partners behind it and their willingness to invest, adapt, and deal with unexpected issues. That calls for shared incentives backed by nonopportunistic behaviors that foster collaboration rather than conflict. Supplier incentives can include access to greater business volumes, longer-term contracts, and even gain-sharing arrangements through which partners share in the cost savings or increased profits generated by improved processes and other innovations they develop.

These smart-control techniques allow companies to achieve some of the benefits of asset ownership without the capital commitment. Many successful asset-light companies use several techniques at once. For instance, McDonald’s embeds former employees in its restaurants by encouraging them to become franchisees. To maintain control of prime locations, McDonald’s owns or leases the properties the franchisees use, which has the added benefits of reducing the amount of capital that franchisees need to invest, filtering out people more interested in real estate investment than restaurant management, and making it easier to replace franchisees. McDonald’s also duplicates what the franchisees do, operating some restaurants itself. This allows the company to experiment with new products and services and set price and quality expectations.

Although McDonald’s has an asset-light model at its core, these smart-control techniques do increase the company’s asset weight: McDonald’s uses 40 percent more assets per revenue dollar than its main competitors, but its shareholder return consistently tops the industry.

Apple became asset light in the late 1990s when Tim Cook, then the chief operating officer, outsourced almost all production and reduced inventories from about one month’s worth in 1996 to two days’ worth by 2000. Apple uses several smart-control techniques. It embeds its engineers by having them work at suppliers’ locations when the company is ramping up production, and Apple stores duplicate the activities of third-party retailers. Apple stores set quality expectations for the Apple purchase experience and send clear price signals. The company also controls specific aspects of its partners’ businesses through its control of the App Store, the only route to market for software developers who want to sell iOS apps. While some criticize the effect this has on competition and freedom of speech, it certainly helps Apple ensure a consistent customer experience. The company’s developer guidelines state, “If your App looks like it was cobbled together in a few days, or you’re trying to get your first practice App into the store to impress your friends, please brace yourself for rejection.”

Nike also applies several smart-control techniques. Although the company does not own any plants, it employs more than 1,000 managers in its supply-chain operations in Asia. The managers work with Nike’s current and possible future suppliers. Nike also has product representatives working in third-party retail stores promoting Nike products and gathering information from the front line. Recently, Nike opened its own retail stores, spurred by the belief that becoming a better retailer would help the company become a better wholesale partner.

Toyota is known for its long-term, trusting relationships with suppliers. Using an open-book approach, the automaker and its suppliers share costs and operating information and work together to reduce costs and improve processes. Instead of squeezing its partners, Toyota ensures that suppliers earn a fair profit. Similarly, Spanish grocer Mercadona has two-way profitability targets with its core private- label suppliers, setting a target profit margin for itself and a target return on capital for its suppliers. This reduces risk for the grocer’s suppliers, giving them the incentive and confidence to invest in innovation and manufacturing capacity.

It is important to note that many valuable incentives—such as long-term guarantees of purchase quantity or price or a guaranteed return on capital for suppliers—can’t be contractually stipulated because unpredictable events could fundamentally disrupt the operations of a company or its suppliers. Unpredictable events include dramatic shifts in demand, natural disasters, and global financial crises. For these reasons, the behaviors of companies and their suppliers are just as important to a partnership as what is written in a contract—and just as essential to building trust. That’s why smart companies aim for targets that benefit suppliers over the long term (almost always at the expense of short-term opportunism) and that can’t be captured in a contract.

Becoming more asset light is, in many cases, the right choice—especially since smart-control techniques can offset the associated trade-offs. In doing so, companies can improve their returns, become more agile, capitalize on the scale and experience of their suppliers, and redeploy their operations more quickly—advantages that are increasingly important in today’s fast-changing global economy.