The Trump administration is exploring a range of policy changes that could have profound implications for the US agricultural sector . Revisions to tax, environmental, trade, and immigration policies have the potential to disrupt the market structure and competitive landscape of the agriculture industry, from farmers to seed producers and grain processors.

The potential magnitude of these policy changes has made this a period of great uncertainty for agribusinesses, raising questions as to whether and how any changes will be implemented. In this environment, any policy revision that is not anticipated could have an outsized impact on agribusiness operations and bottom lines. For this reason, it’s no longer viable to delegate responsibility for policy issues to public relations or lobbyists. Companies need to make these issues a top strategic priority.

Four Key Policy Areas

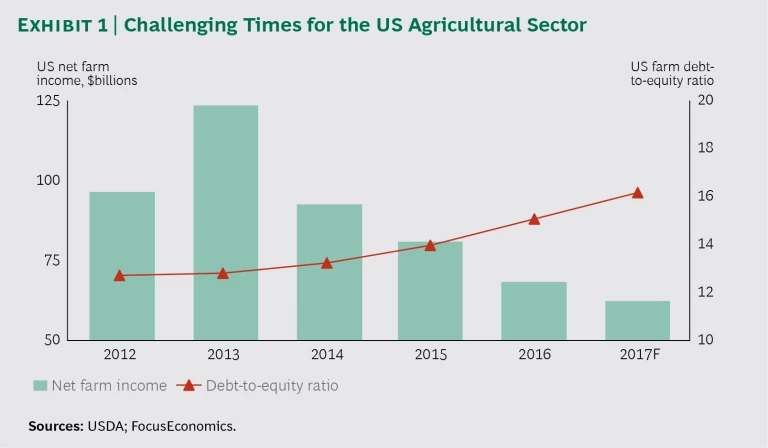

These challenges come at a time when the agriculture industry is already treading water. With most commodity prices at all-time lows, many farmers are continuing to experience net operating losses and rising debt levels. As a result, the farm debt-to-equity ratio has reached its highest point in the past five years. (See Exhibit 1.)

Navigating risk in this environment means first coming to an understanding of what is likely or not likely to happen and then implementing an approach that both manages the risks around the downside and seizes any potential opportunities.

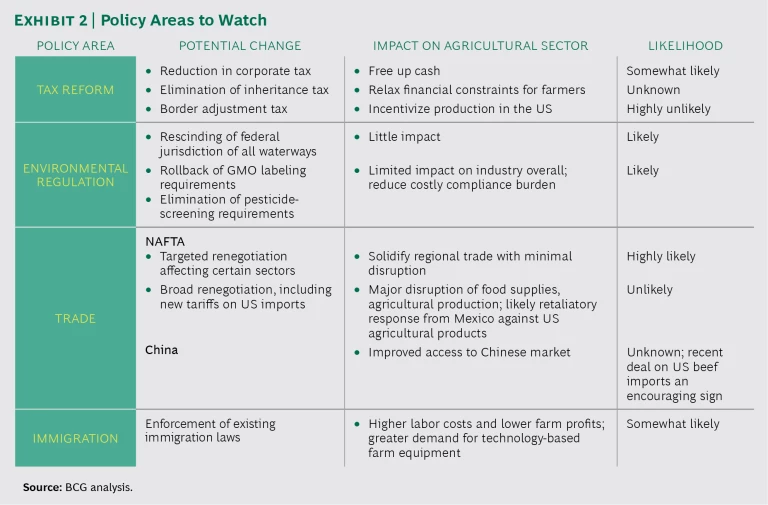

By our assessment, potential changes in four policy areas are especially important. They vary both in their probability and in their potential impact on the agricultural sector. (See Exhibit 2.)

Tax Reform. Given the support demonstrated so far by the Senate and House of Representatives, simplification of the tax code is somewhat likely. Agribusinesses stand to benefit from reforms that would reduce taxes and free up capital for investment. A repatriation proposal would give companies a one-time opportunity to pay lower taxes on profits earned overseas, providing a cash windfall. And tax code simplification would ease the currently complicated tax management process that is faced by most farmers.

Agribusinesses should plan for ways to either invest the capital resulting from lower taxes in innovation or return it to shareholders. Global companies with headquarters or operations in the US should likewise develop a plan to make use of their repatriated cash. Those that establish plans in advance will have a strategic advantage because they will be able to invest in innovation and operational efficiency before their peers.

Easing of Environmental Regulations. The administration has proposed rolling back an Obama era regulation that requires the labeling of foods containing genetically modified organisms, as well as one that establishes EPA screening programs for new chemicals. Rollbacks of either regulation would benefit the agricultural seed and chemical sectors and provide farmers with additional options for inputs.

A third regulation, the Waters of the United States rule, significantly expanded the bodies of water under federal jurisdiction. Although bodies of water on active farms were explicitly excluded, the rule raised farmers’ concerns that the federal government might decide to include waters on farms after all. A recent executive order directing the EPA to revise or rescind the rule probably came as welcome news.

Trade. Because US agricultural productivity over the years has grown faster than domestic consumption, exports have become an increasingly important source of farm income. For farmers already facing a global supply glut and low prices, agricultural trade agreements offer the most viable path to stronger economics. But because agricultural trade agreements often involve hot-button issues of cultural identity, health, and the environment, they are notoriously difficult to negotiate.

- Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The administration’s decision to withdraw from the TPP came as a blow to US farmers. The agreement, which was awaiting ratification, would have slashed tariffs on exports to and imports from the ten member states, which make up 40% of the global economy. In addition, since Canada and Mexico are part of TPP, US producers would have benefited in certain sectors in which the agreement offered better market access than NAFTA does. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the TPP would have added approximately $4.4 billion to US annual farm income.

President Trump’s plan to set up bilateral agreements with individual countries may well prove beneficial to farmers in the long term, although they could experience financial stress while waiting for these agreements to be negotiated.

- North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In May, the Trump administration notified Congress of its intention to renegotiate NAFTA and its hope to complete negotiations by the end of 2017. The administration wants to focus on “modernization,” which will likely include the terms already embedded in TPP regarding digital trade, IP protection, and labor standards. Mexico is a top destination for US dairy, pork, corn, and rice, while for its part the US relies heavily on Mexico for imports of fruits and vegetables. Mexico would not take major changes lightly, as its interest in setting up corn purchase agreements with Brazil and Argentina indicates. The loss of the United States’ largest foreign market for corn could be disastrous for farmers and other parts of the value chain. (See “Blurred Boundaries on Beef Imports.”)

BLURRED BOUNDARIES ON BEEF IMPORTS

Given the high stakes, we believe that changes to NAFTA related to agriculture are unlikely. It is more likely that changes will focus on the manufacture of industrial and consumer durable goods. And in that case, NAFTA should be ratified quickly and easily. However, should negotiations stumble or the US choose to take some action against Mexico, the agricultural sector would be an obvious target for Mexican countermeasures.

- China. Trade relations with China are another source of uncertainty. A recent agreement that allows US beef imports into China, the world’s fastest-growing market, is an encouraging sign. It’s less clear, however, what the impact will be of a provision allowing China to export cooked poultry to the US.

Immigration. The US agriculture industry is uniquely vulnerable to stricter enforcement of immigration laws. In 2014, according to the Pew Research Center, 26% of farm workers in this country were unauthorized. The Federation for American Immigration Reform estimates that stricter enforcement of US immigration laws could drive up labor costs by as much as 10% to 12%.

A large labor shortage will drive up costs, potentially leaving high-value fruits and vegetables rotting in US fields. But it will also increase demand for technology-based farm equipment like vegetable harvesters, thus creating potentially strong opportunities for certain parts of the value chain.

Other Issues. There are various political hot-button issues about which the administration has offered no clear direction. Take the farm bill, for example, which is renegotiated every five years. So far, the president has said little about what he envisions for the bill. The administration’s recent budget proposals, however, include significant cuts to US Department of Agriculture funding, which would reduce the federal subsidies for crop insurance that protect farmers from crop failures or price drops. This provision would exacerbate farmers’ rising costs and limit their investments in equipment, new seeds, fertilizer, and crop protection products. A bill with such negative ramifications, however, is unlikely to become law.

Another headline-grabbing issue is the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program, which requires renewable fuel to be blended into transportation fuel in increasing amounts every year until 2022. Currently, more than one-third of the US corn crop goes into the manufacture of ethanol and ethanol byproducts like distillers grains, leaving little room for growth.

The fate of the RFS program is far from certain. But even if it is rolled back, ethanol demand is unlikely to be significantly affected, barring any major change in restrictions on fuel additives.

Three Key Practices

Given the uncertainty about how these potential changes in policy will play out, agribusinesses’ best bet is to make them an integral part of business planning efforts and the CEO agenda. Three practices are crucial.

- Imagine future scenarios. The importance of specific issues arising from any policy changes will vary from subsector to subsector and even from company to company. That makes it essential to do scenario planning that provides a firm understanding of each issue’s potential impact on your company’s business and operating models and those of your competitors. When an issue affects competitors differently, the market landscape will change, creating new opportunities for strategic advantage.

- Plan for contingencies. After your team has laid out all the scenarios, the next step is to develop operational plans for every scenario with potentially significant ramifications. These plans need to be detailed enough that, if a particular scenario suddenly comes to pass, you will be able to make the necessary changes to your operations in a matter of hours or days. Such speed is critical to thriving amidst market disruption.

- Actively monitor the policy landscape. Once scenario and contingency plans are in place, it is important to monitor the status of the most relevant policies on an ongoing basis. Drawing on information gleaned from speeches, policy statements, and active networking, your leadership team should revisit the scenarios to determine if they are more likely or less likely than previously thought and adjust priorities accordingly. The senior management team, heads of business units, and operations leaders should all play a role in this effort.

Adopting a New Mindset

Although much about the administration’s agricultural policies is yet to be spelled out, one thing is clear. Any major change in policy has the potential to disrupt the agriculture industry and the current strategic landscape.

For this reason, nothing less than a wholesale shift in mindset is in order. (See Exhibit 3.) Agribusiness companies need to stop treating administration policies only as public relations issues and start treating them as a critical part of the business agenda. They need to develop a comprehensive strategic response with the same rigor that a 20% change in the price of corn would require.

This is a job for the CEO and the senior management team. The C-suite should stop relegating responsibility for managing policy risks to the risk management team. Only then will it be possible to seize opportunities in new market conditions as they emerge.

To be sure, there is no fail-safe response to some policy changes. Still, despite the policy uncertainty, the companies that are best able to identify and exploit the opportunities stand to gain in the long run.