Given all the effort that companies have put into diversity , it’s perplexing that they are not making faster progress. Over the past few years, press attention and awareness have expanded the focus on obstacles that employees in diverse groups, particularly women, face at work. In response, companies have launched even more programs to address these obstacles, yet few of these efforts have yielded results. Although nearly all companies have diversity programs in place, according to our research, only about a quarter of employees in diverse groups said that they have personally benefited.

Most corporate leaders now understand that in today’s business environment, companies must achieve diversity if they want to acquire and retain talent, build employee engagement, and improve business performance. (See “ How Diverse Leadership Teams Boost Innovation ,” BCG article, January 2018.) But many leaders still have blind spots regarding diversity. They underestimate the obstacles confronting an employee of a diverse group, perceiving a workplace with far less bias than actually exists. They launch programs that they think will yield improvements, but their decisions are based on gut instinct rather than proven results. Unless they acknowledge their blind spots, these leaders won’t make meaningful progress.

We recently surveyed roughly 16,500 people worldwide to identify the most effective diversity and inclusion measures. Our investigation builds on previous BCG research into gender diversity, including a landmark study in 2017. (See Getting the Most from Your Diversity Dollars , BCG report, June 2017.) For our current analysis, we broadened our lens to include diversity in two additional dimensions: race and ethnicity and also sexual orientation. (See the Appendix for details on the methodology.)

Through that research, we identified specific solutions that companies can implement to accelerate their progress on diversity. (See “Key Findings.”) These solutions fall into three categories:

- Back-to-basics measures that all groups, regardless of age, gender, race or ethnicity, or LGBTQ status, agree are necessary and effective

- Proven measures that employees of each diverse group—along with management—agree are effective

- “Hidden gems” for each group—initiatives that members of that group cite as effective yet are undervalued by company leaders

Key Findings

Key Findings

- Despite greater attention to and increasing investments in improving diversity related to gender, race and ethnicity, and sexual orientation, gains have been far from impressive. Approximately 98% of companies have established a gender diversity program, but only about a quarter of employees in diverse groups said that they have personally benefited. (See the exhibit below.)

- A key impediment to progress is that men age 45 or older, commonly those who lead decision making in corporate environments, underestimate—by 10 to 15 percentage points—the obstacles in recruiting, retention, and advancement reported by female, racially or ethnically diverse, and LGBTQ employees.

- To improve, companies need to invest in back-to-basics measures that all respondents agree are effective. These include setting antidiscrimination policies, providing formal training to mitigate biases and increase cultural competency, and removing bias from evaluation and promotion decisions.

- Proven measures for individual groups include those that the majority and members of those groups say are effective.

- Most important, our research identified “hidden gems”—measures that leadership underestimates but diverse employees consider critically important.

Women, for example, have a strong interest in indicators showing that advancement is possible. These include visible role models, parental leave, appropriate health care coverage, and assistance with childcare (such as on-site facilities and emergency backup care).

Racially and ethnically diverse employees look for fairer recruiting and advancement decisions, with sponsorship and individual roadmaps for advancement.

LGBTQ employees are hoping for indications of less bias in the work environment, including structural changes such as nonbinary gender designations and gender-neutral restrooms.

- Finally, companies need to focus on implementation, exemplified by strong leadership commitment, actions that are tailored to drive change (for example, balancing top-down and bottom-up initiatives), and rigorously tracked KPIs.

Companies cannot simply launch programs and expect results. Instead, they need a strong focus on implementation, just as they would for any other business priority. Specifically, the success of each of these initiatives requires leadership commitment, a tailored approach that is based on the unique needs of the organization, and metrics for gauging progress. Furthermore, they need to involve their employees throughout—both in the choice of specific solutions and in assessing the impact of ongoing measures.

Lingering Obstacles and Gaps in Awareness

Clearly, companies have not made much progress in their ability to deal effectively with diversity, and the problem is acute at the leadership level. Among Fortune 500 CEOs at the time of publication, only 24 are women (less than 5% of the total), only three are black, and only three are openly gay, including just one lesbian. In fact, this kind of homogeneity among leaders is a key part of the problem at lower levels of companies. Our data shows that most company leaders—primarily white, heterosexual males—still underestimate the challenges diverse employees face. These leaders control budgets and decide which diversity programs to pursue. If they lack a clear understanding of the problem, they can’t design effective solutions.

If leaders lack a clear understanding of the problem, they can’t design effective solutions.

When asked if they see obstacles to diversity and inclusion at their company, more than a third of diverse employees said yes. Half of all diverse employees stated that they see bias as part of their day-to-day experience at work. Half said that they don’t believe that their companies have the right mechanisms in place to ensure that major decisions (such as who receives promotions and stretch assignments) are free from bias. By contrast, white heterosexual males, who tend to dominate the leadership ranks, are significantly more likely than employees in diverse groups to say that the day-to-day experience and major decisions are free of bias. (To be clear, our overall analysis included respondents worldwide, but in this paper, we present the results for race and ethnicity from three countries: the US, the UK, and Brazil. The respondents in other countries cite other ethnic groups as the majority.)

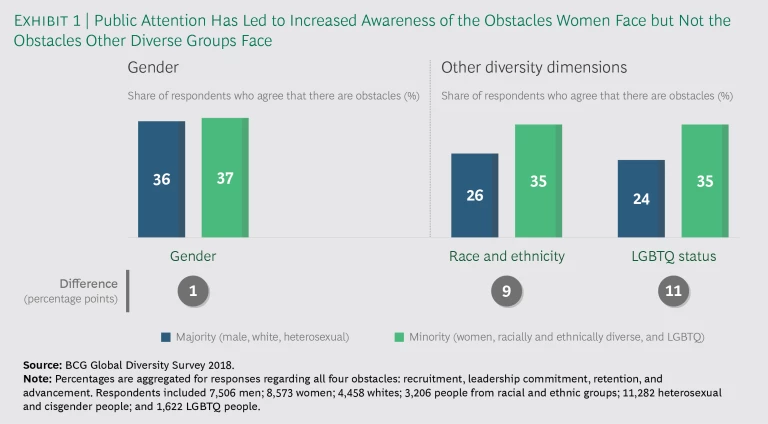

In terms of gender diversity, leaders are starting to get it. The disparity between the perceptions of leaders and those of women across all levels of the organization is relatively small. Men are more likely to see the obstacles that hold women back at work, probably because lately, the media has been covering such issues more openly. Yet the difference in the perceptions of straight, white men and those of people of color and LGBTQ employees remains significant. For example, just 26% of straight, white men see obstacles to the advancement of racially or ethnically diverse employees, compared with 35% of employees in that group. And straight white male leaders and LGBTQ employees indicate a similar difference in perception. (See Exhibit 1.)

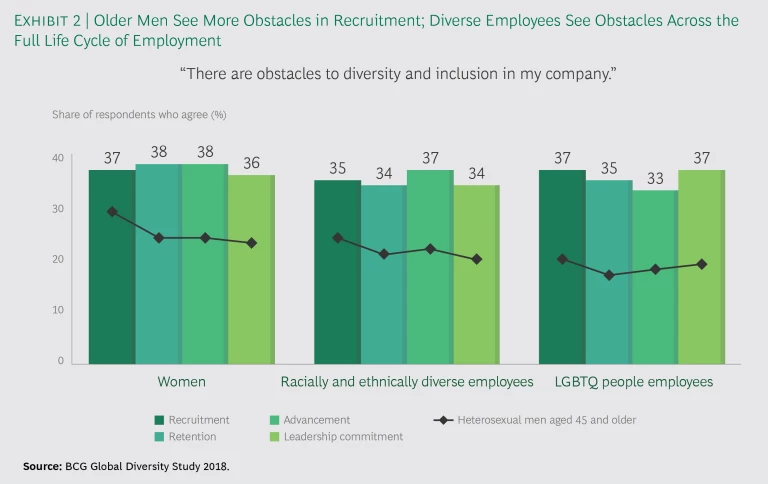

In addition to underestimating the problem, leaders tend to see it in the wrong place. We break the obstacles to diversity down into four areas: recruiting, retention, advancement, and leadership commitment. Many leaders believe that the recruiting phase presents the biggest obstacles—particularly for women and racial and ethnic minorities. It is not, however, that simple. Hiring people from diverse groups is easier than successfully addressing the deep-rooted cultural and organizational issues that those groups face in their day-to-day work experience.

And, in fact, members of diverse groups do see things differently. Because they have first-hand experience of the daily biases that keep them from staying at an organization and rising through the ranks, they see more obstacles across the entire employee life cycle: recruiting, retention, advancement, and the commitment of leaders.

It’s easy, therefore, to see how companies can spend money on diversity initiatives that don’t generate results. The senior leaders—primarily older men—who make decisions about how much to invest in diversity and which initiatives to fund lack a clear understanding of how big the problems are or where those problems lie. (See Exhibit 2.)

There is, however, one reason for optimism: our research shows that many younger men are more attuned to the obstacles that confront employees in diverse groups. (See the “Younger Men Are an Untapped Resource.”)

Younger Men Are an Untapped Resource

Younger Men Are an Untapped Resource

If there is a bright spot in our findings, it’s that the young heterosexual men in our sample (those younger than 45) are more attuned to diversity and inclusion than older heterosexual men—and therefore more likely to be empathetic and eager to address those issues. Specifically, the younger men’s perceptions of the obstacles that diverse employees face tend to be closer to those of people in those groups.

For example, only 25% of older heterosexual men see obstacles for women in the workplace, while 35% of younger heterosexual men agree that there are obstacles, closer to the 37% of women who cite those concerns. The same difference between older and younger heterosexual men shows up in racially and ethnically diverse employees, and those in the LGBTQ category.

This finding makes intuitive sense. Younger employees are less likely than older employees to see diversity as a new concept that they must incorporate into their thinking. Rather, all their lives, diversity has been an issue in the public eye.

For companies, the clear takeaway is that they must engage younger employees in understanding—and tackling—the obstacles to greater inclusion.

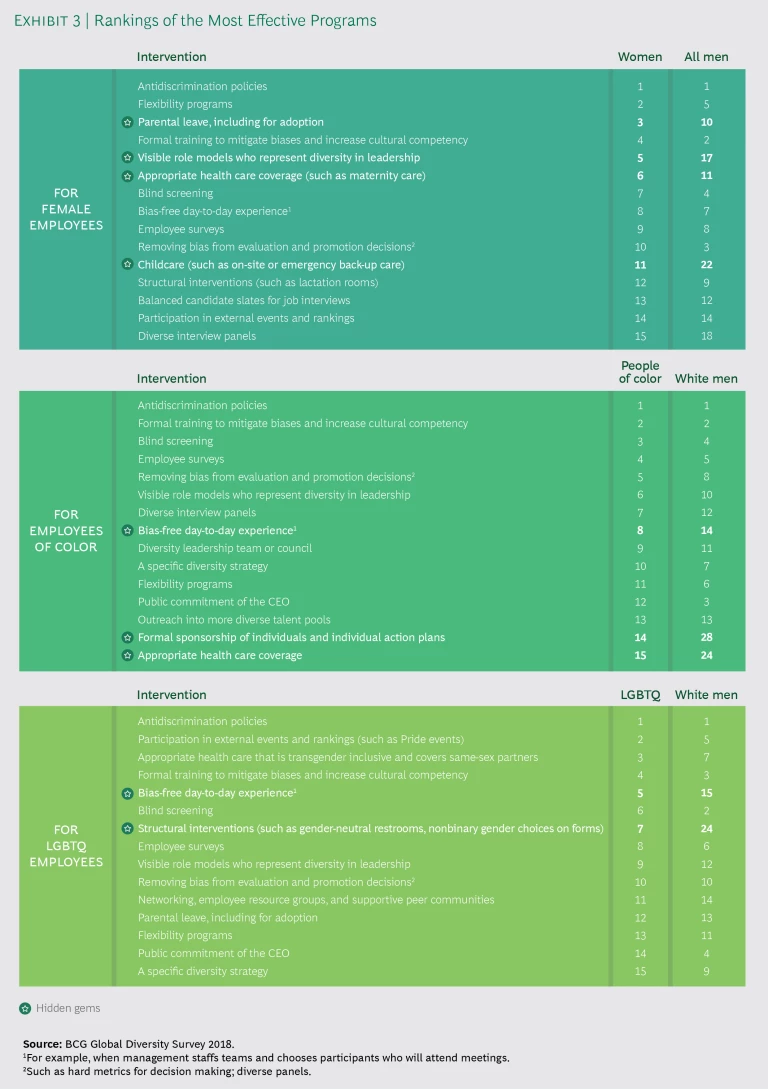

How to get better? We asked survey participants to evaluate the effectiveness of 31 diversity initiatives. (See Exhibit 3.)

On the basis of their responses, we have identified three categories of measures:

- Back-to-Basics Measures. All groups, regardless of age, gender, race or ethnicity, or LGBTQ status, agree that these are necessary and effective measures that should be priorities for all organizations.

- Proven Measures. Each diverse group has its own list, and management and employees in each group agree that these measures are effective.

- Hidden Gems. Members of each group cite certain measures and initiatives as effective, but these measures are undervalued by company leaders. These reflect the biggest blind spots, so organizations should prioritize those identified measures and initiatives that correspond to their diversity objectives.

Exhibit 4 shows a breakdown of the most effective initiatives, by group.

Getting Back to Basics

The first set of solutions includes back-to-basics measures. All were ranked in the top ten by all employees regardless of age, gender, race or ethnicity, or LGBTQ status, and all are aimed at reducing bias. These should be priorities for any organization that wants to improve diversity.

Antidiscrimination Policies

In the past, HR departments have treated antidiscrimination policies as a compliance requirement—statements that lawyers draft and leave unread on the company intranet. The prominence of such policies in employees’ responses indicates that companies should do far more.

A well-crafted policy can effectively lay out the company’s values, and frequently and explicitly communicating such a policy to employees sends a signal that the company takes the issue of diversity seriously. Unfortunately, too few companies consistently follow their policies or take decisive action when problems arise.

According to the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), almost half of LGBTQ workers believe that even if an antidiscrimination policy is in effect, it won’t be enforced if their own supervisor is not supportive of the LGBTQ community. As a result, many employees in this group are reluctant to report issues.

Training to Mitigate Biases and Increase Cultural Competency

The second back-to-basics measure is formal training to mitigate biases and increase cultural competency. Most managers and executives don’t think that they are biased, yet bias is wired into human nature: biases stem from the genetic shortcuts that help our brains recognize patterns. Overcoming these “unconscious” biases can be difficult, but formal training can help employees identify their biases and understand their effect.

Most managers and executives don’t think that they are biased, yet bias is wired into human nature.

It’s worth noting, however, that there are many ways to get such training wrong. For example, some companies hire outside vendors to come in for a single session lasting a few hours, but this approach is insufficient for addressing such a pervasive challenge. Others train in a way that puts employees and managers on the defensive—and can actually backfire. Given these risks, companies need to make thoughtful choices regarding how they implement this kind of training. The best programs lead with the ideas that everyone has biases and that although biases may be a normal part of being human, unconscious biases do have harmful effects. It’s critical that programs focus on actionable strategies, and they must be complemented by changes to programs and policies.

To maintain the momentum initiated by formal training, companies should look for ways to foster informal discussions among employees about bias and cultural issues. Many companies host these kinds of discussions among small groups. (BCG’s program is called Authentic Conversations.) These generally unstructured sessions, led by a moderator or facilitator, provide an opportunity for employees to practice using the tools they acquire during the training, ultimately increasing cultural competency, awareness, understanding, and inclusion.

Removing Bias from Evaluation and Promotion Decisions

Respondents in all categories highlighted the importance of eliminating bias from decisions related to evaluations and promotions. Many companies maintain that these processes are bias free, but rigorous examination of the data proves otherwise. Companies should start by comprehensively tracking diversity metrics relative to promotions. Next, having established clear criteria and hard metrics for employee evaluations—and promotion decisions—they can strip bias out of the decision-making process, demystifying the process for diverse employees who may not have access to insider networks and information. Rigorous tracking of promotions and evaluations can highlight areas in which biases may exist—both who is (or is not) getting promoted across diverse populations and whether evaluations include questions or criteria that indicate systemic bias because certain groups consistently perform at different levels. (See “Boosting Diversity at Law Firms.”)

Boosting Diversity at Law Firms

Boosting Diversity at Law Firms

The legal profession has long struggled with diversity. The Diversity Lab is an incubator dedicated to changing that. One of its key initiatives, born out of a 2016 diversity “hackathon,” is the Mansfield Rule, named for Arabella Mansfield, the first female attorney in the US. The goal of the Mansfield Rule is to ensure a level playing field in the selection process for leadership positions such as equity partner and key governance roles.

Law firms can become Mansfield certified if the slates they consider for leadership positions include at least 30% women, racial or ethnic minorities, and members of the LGBTQ community. Studies have shown that 30% is the threshold for changing mindsets regarding diversity. (The inclusion of just one candidate for an open position is easily dismissed as tokenism.)

Although the rule itself is fairly narrow, adopting a concrete, easy-to-grasp measure such as the Mansfield Rule has many benefits, according to Lisa Kirby, managing director at Diversity Lab. “It’s not just throwing more names into the ring. It has really changed the conversation. It brings diversity to the forefront when people are making these critical decisions around promotions and leadership. And what were previously often quick, gut decisions are now more structured, thoughtful discussions.”

The Mansfield Rule includes two additional components:

- Rigorous Tracking of the Diversity of Candidate Slates for Key Positions. Previously, only 60% of firms tracked diversity among equity-owning partners, 30% among leadership appointments, and 20% among senior hires. Now, 100% of participating firms track their performance across all three metrics.

- Clearer Job Descriptions for Leadership Positions and Transparency into the Decision-Making Process. The number of firms that make the responsibilities and requirements for open positions transparent to their staff has nearly doubled, from 28% to 55%.

More than 40 top-tier firms signed up for the first pilot in 2017, and that number exceeded 60 firms in 2018. After just six months’ participation in the program, more than a third of those firms reported an increase in the representation of women and people of color across all areas tracked.

In addition, specific training can help managers structure feedback so that it corresponds more closely to the completion of projects and goals. This helps make evaluations less dependent on personality-based observations that may be subject to bias.

Proven Measures for Each Diverse Group

In addition to identifying the three back-to-basics measures, our research highlighted proven interventions for each of the three groups we analyzed. All of these solutions were consensus picks by members of the specific group—women, people of color, or LGBTQ employees—and majority respondents outside of those groups.

- Women. For women, flexible-work programs—such as part-time positions, the ability to modify working hours, and the opportunity to telecommute—remain highly valued. Women ranked them the second-most-effective measure. Many organizations now offer these programs, yet their implementation can vary widely.

- People of Color. Employees of color see measures related to recruitment as critical. For example, they ranked blind screening of résumés during recruitment third and diverse interview panels for job candidates, seventh.

- LGBTQ. Employees in the LGBTQ group ranked participation in external events (such as Pride activities) second: it sends an emphatic signal that the company is an LGBTQ-friendly organization that values its employees. In addition, this group ranked appropriate health care coverage third. Coverage can include equivalent-partner or spousal benefits as part of the employee’s health care plan, in addition to life insurance, relocation assistance, adoption assistance, and transgender-inclusive health care coverage. As of 2018, nearly 60% of Fortune 500 companies were providing such benefits, and the number is growing—up from none in 2002 and 28% in 2012.

Hidden Gems for Each Diverse Group

In addition to measures that are valued by both the diverse groups and the majority, our analysis identified hidden gems—measures that majority respondents labeled ineffective while diverse employees said that they consider them effective and valued. For each of these ranking disparities, members of the majority group were asked not whether they value the initiative but whether they think the diverse group values it.

Hidden Gems for Women

For female employees, hidden gems are those that provide a viable path forward and give them the tools to balance career and family responsibilities. Specifically, the top hidden gem for women is having visible role models in the leadership team: this ranked 5th among women and 17th among men. Many women consider it dispiriting that they don’t see many females whose higher positions show that advancement is possible. They want to see role models who understand their situation or have similarly struggled to balance work and home life in the face of societal expectations for women.

Women want tools that can help them balance career and family responsibilities.

Many male senior executives have spouses at home who handle most of their families’ domestic responsibilities. By contrast, midcareer women are far more likely to be part of two-career households. (See “ Making the Workplace Work for Dual-Career Couples ,” BCG article, July 2018.) Companies should spotlight their female executive-team members so that rising women below them see a working model of success. One North American financial services company wanted to change the culture within certain units and create visible role models for junior women, so it made a point of moving senior women into units that previously had had all-male leadership.

In addition to visible role models, women want tools that can help them balance career and family responsibilities. They are looking for parental leave (ranked 3rd by women but 10th by men), appropriate health care coverage (6th versus 11th), and childcare assistance such as backup or onsite childcare (11th versus 22nd). Medical care that covers pregnancy, appropriate time off to recover from childbirth and provide care for their infants, and continued support throughout childhood—in the form of health coverage and childcare support—all enable women to continue to thrive in their careers regardless of their family status. Responsibility for family and childcare continues to fall disproportionately on women, so companies that want to improve gender diversity need to consider how these measures can help boost their overall gender diversity. (See “Showing Women the Path to the Top at Unilever.”)

Showing Women the Path to the Top at Unilever

Showing Women the Path to the Top at Unilever

Amanda Sourry was appointed president of Unilever North America and global head of customer development in January 2018, having served on the global leadership executive committee since 2015. A mother of two who worked part-time for seven years when her children were younger, she is passionate about serving as a role model for other women at Unilever. “When you see it, you can be it,” she says. Sourry has long advocated for diversity and for supporting working parents both within Unilever and externally.

Unilever, which was ranked number one in Working Mother magazine’s ranking of best companies in 2018, provides a battery of support for families. The company provides 16 weeks of maternity leave, 8 weeks of paternity and adoptive leave, extensive coverage of fertility treatments, lactation rooms and free breast milk shipping for traveling mothers, backup childcare, and support for children with disabilities.

Under Sourry’s leadership, Unilever not only provides these benefits but also actively works to change the company culture so that women—and men—feel empowered to take advantage of these options. For example, since the company started its push to normalize paid paternity leave, the number of employees who use it has increased significantly. A recent five-member panel on parental leave included four males and only one female, a reversal of the typical gender dynamics. Having both men and women celebrate time off for family reduces the motherhood penalty that confronts many working women.

Unilever is also fostering the conversation beyond its own walls. Its Dove Men+Care brand has started a #DearFutureDads campaign that broadly advocates for paid paternity leave.

Unilever believes that these initiatives not only help build a strong talent pipeline but also help all employees fulfill their potential. Women now make up more than 50% of Unilever’s managers. They are enjoying the benefits of being part of a culture that offers a clear path forward and the support to navigate it.

Hidden Gems for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Employees

The good news for employees of color is that the majority is largely in tune with the interventions that they believe are most effective: there is agreement on four of the top five. The majority’s blind spots are in the estimation of the importance of measures that advance people of color who are already employees.

Previously, we discussed stripping bias from critical promotion decisions (ranked 5th by employees of color and 8th by the majority). Another measure that does a good job of promoting the advancement of diverse employees is formal sponsorship of individuals and the provision of individual roadmaps for advancement (ranked 14th by employees of color and 28th by white men). These programs pair a high-potential individual with a senior person in the organization who can help open doors, advocate for promotion and career advancement, and navigate to new opportunities and “hot” assignments. It’s not uncommon for informal networks to form among people with similar backgrounds, leaving out diverse employees who see fewer people like themselves in leadership. Sponsorship programs fill this gap. They show diverse employees that the organization believes in their potential and is invested in their success. More important, they provide the access to leadership that is necessary for advancement. (Critically, sponsors need not be from the same ethnic group as sponsorees, though that’s preferable.)

In addition, employees of color cite the importance of eliminating bias from the day-to-day experience, including how teams are staffed or meeting attendance is decided (ranked 8th by people of color but 14th by white men). Such day-to-day decisions might seem insignificant, but their importance accumulates, ultimately impacting decisions related to promotions and key assignments and, consequently, job satisfaction and retention. Employees in these groups want to be valued equally, but they are convinced that they must be continually on guard against bias, leading to what Catalyst, a nonprofit focused on gender and diversity in the workplace, terms an “emotional tax” that diverse employees must pay every day.

Hidden Gems for LGBTQ Employees

The top hidden gem for LGBTQ employees is a bias-free day-to-day experience (which they ranked 5th, compared with 15th by the control group of heterosexual men). Like racially and ethnically diverse employees, LBGTQ employees want to have equal opportunities day-to-day and to come to work without fear of being judged for who they are. (See “Fostering LGBTQ Inclusivity at Barclays.”) A 2018 HRC survey showed that despite corporate antidiscrimination policies, nearly half of LGBTQ workers are still closeted at work, and more than half report hearing jokes about lesbians or gays at least occasionally. Companies need to actively look for unconscious bias and create a culture in which people have no tolerance for jokes or derogatory statements and in which LGBTQ employees can be their authentic selves. A BCG survey of 4,000 LGBTQ employees employees at various companies in 12 countries found that although 80% said that they were ready to disclose their sexual orientation at work, only 50% had actually done so.

Fostering LGBTQ Inclusivity at Barclays

Fostering LGBTQ Inclusivity at Barclays

Barclays, a leading UK bank, has a long-standing global commitment to five aspects of diversity and inclusion: disability, gender, LGBTQ, multicultural, and multigenerational. In particular, Barclays has long been a leader in LGBTQ advocacy. (The company refers to LGBT+ diversity, rather than LGBTQ, which is used in the US.) Barclays, which launched Spectrum, its LGBT+ employee network, in 2002, offers cross-industry mentoring to LGBT+ employees, provides unconscious-bias training for all managers, and encourages allies to challenge any inappropriate behavior they might see in the workplace.

For Barclays, internal support for the LGBT+ community has advanced hand-in-hand with external activities, becoming part of the company’s culture and business strategy. “We want not just our colleagues but also our clients and customers to feel free to express who they are,” says Mark McLane, who was formerly the global head of diversity and inclusion at Barclays. “Our colleagues report through our employee opinion survey that 91% globally feel they can bring their whole selves to work.”

For the past five years, Barclays has served as the lead sponsor of Pride in London, with more than 400 employees taking part. The bank has used this forum to launch key customer initiatives, including a mobile-banking platform. “Pride allows us to show our commitment to our LGBT+ employees, who see their community celebrated, and we are able to promote inclusion in the broader community,” McLane says. Over the past three years, Spectrum has distributed more than 10,000 rainbow lanyards for the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia.

The bank’s work on transgender inclusion is another example of how diversity and inclusion apply both internally and externally. In addition to offering transgender-inclusive health care benefits to employees, the company ensures that transgender customers feel included. For example, it changed its call center processes after realizing that voice recognition software was disproportionately flagging transgender customers as security risks because of a perceived mismatch with their listed gender. Barclays recently instituted the gender-neutral title Mx. as an option for both employees and retail bank customers. “Whether or not you use it, if it’s there, it means you count,” McLane says.

LGBTQ employees cited structural interventions that accommodate a broader gender orientation than simply male or female (ranked 7th, compared with 24th by heterosexual men). These interventions might include the provision of gender-neutral restrooms and the redesign of employee surveys to include nonbinary gender choices. Although such measures might appear insignificant to the majority, they signal a company’s commitment to diversity and understanding of the issues facing LGBTQ employees.

Getting Implementation Right

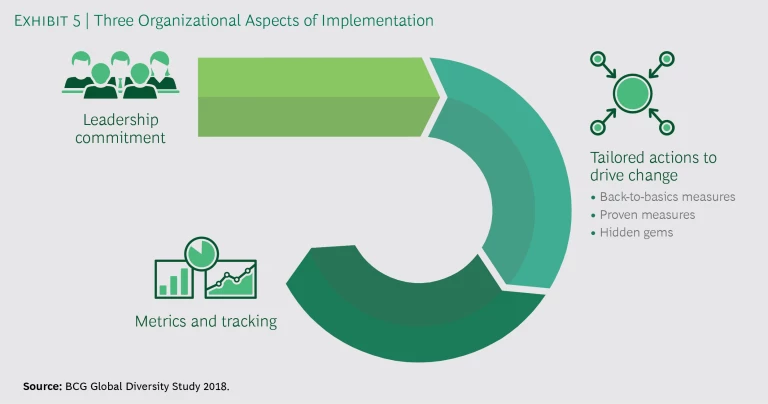

Our analysis pointed to several organizational aspects of implementation. Companies that are developing diversity and inclusion initiatives need to apply the same methodology to those efforts that they apply to any other business priority. (See Exhibit 5.)

Leadership Commitment

Successful implementation requires true leadership commitment—much more than superficial words or platitudes. Leaders, those in the C-suite and upper and middle management, must build a clear case for change, determining the company’s current performance in terms of diversity and communicating the ways that a more diverse workforce and leadership team will lead to better performance. Organizations should also challenge leaders to work with diverse mentees to better understand the challenges that people in diverse groups face and to demonstrate their own personal commitment to change.

Next, they should set strategic goals, prioritizing them on the basis of the company’s biggest diversity challenges. Generally, this determination is the result of listening to the diverse employees who are the focus of the initiatives to make sure that the initiatives meet specific problems that their diverse population experiences.

Tailored Actions to Drive Change

The measures we’ve discussed can serve as a guide, but they must be tailored to each company, using its specific culture and starting point to determine the best course of action. Companies working to reduce bias can consider a variety of top-down and bottom-up approaches.

For example, top-down approaches could include corporate-level training, initiatives for midlevel managers who actually do the work, and programs that track promotion and pay data across diversity cohorts. Bottom-up approaches could include measures that help managers think about the daily impact of their actions—who they bring to important meetings, how they run meetings and deal with interruptions, and even who they ask to organize the office holiday party.

Furthermore, many companies make the mistake of launching a program without first doing the hard work of analyzing how it will function on a day-to-day basis and how it will change the employee experience. Or they launch programs within HR without involving affected employees in the design and assessment of those programs. Mainstreaming each intervention—or securing buy-in and promotion across business units, at every level, and critically, by members of the majority group—is necessary for any intervention to take hold and be effective.

The number two intervention for women—flexible-work programs—provides a good example. Too many companies have established flex programs without also addressing the culture shift required to make them realistic options.

There is, for example, a stubborn perception that flexible work is only for mothers with young children and will derail a person’s career trajectory. Many women simply don’t believe that these programs support them on a leadership path. The best flex programs are “reason neutral,” designed not only for women or just one type of situation. Instead, they are developed with broad input that ensures that they function for everyone involved and are supported with the appropriate resources. And they are modeled by senior leaders, including men. (See “Getting Flexible Work to Stick at PepsiCo Australia & New Zealand.”)

Getting Flexible Work to Stick at PepsiCo Australia & New Zealand

Getting Flexible Work to Stick at PepsiCo Australia & New Zealand

PepsiCo Australia & New Zealand (ANZ) had established flex programs, but adoption was low. “We had all the right policies, benefits, and procedures in place, but they weren’t being championed or embedded into the culture,” said Shiona Watson, senior director of human resources at PepsiCo ANZ.

The key to changing that was the company’s One Simple Thing initiative, which provides a framework that allows employees to talk to their managers about the one thing that is most important for them personally in crafting a more flexible and sustainable work-life balance.

Employees—women, men, parents, and nonparents—across PepsiCo ANZ engage in such discussions, which can lead to changes in work schedules. Mothers and fathers may opt to come in late after dropping their children at daycare or school or to leave early to pick them up, depending on their family needs. Or an avid surfer may take time off to hit the waves.

PepsiCo ANZ credits the following aspects of the program:

- The program works to ensure that senior leaders—both women and men—are visible role models for flexible ways of working, and the company supports an initiative that has leaders “leave loudly” when departing work for personal reasons.

- It empowers direct managers to make decisions about what works for their own teams. In this way, the program works for managers and employees.

- The company extends flexible-work concepts to all employees. In manufacturing units, not all options—such as adjusting an employee’s working hours—are available. But PepsiCo ANZ still seeks to work within the constraints of those facilities to offer alternatives, such as different shift patterns, working only on certain days of the week, or part-time employment.

- It leverages technology to make flexible work easier.

PepsiCo ANZ has seen clear benefits from the program, which has allowed it to tap into broader talent pools, retain its best and most diverse talent, and enhance the company’s culture.

Metrics and Tracking

Establishing and tracking clear metrics is critical. Top-performing companies set clear, quantifiable diversity goals, measure their progress over time, and foster transparency by reporting their progress publicly.

Establishing and tracking clear metrics is critical.

Perhaps most important, these organizations use KPIs to hold leaders accountable for results. (See “ Measuring What Matters in Gender Diversity ,” BCG article, April 2018.) Companies can use their measurements to refine the approach, building on successes and rethinking initiatives that don’t lead to quantifiable results.

For example, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), with a portfolio totalling more than $260 billion, set a long-term goal of achieving a 50/50 hiring ratio of female talent to enhance performance and increase the diversity in their workforce. Impressively, in an industry not known for its gender diversity, they have achieved it alongside strong and sustainable financial returns. Now, the organization is working toward more equal representation across the leadership ranks in investment departments, already experiencing an 8% increase since 2016.

There’s still room for progress in achieving corporate diversity and inclusion. But the good news is that there are many measures that diverse employees already find effective in promoting a more diverse workplace. For leaders who want to make a difference but aren’t sure how, this report recommends specific actions that leaders can take—starting today—to create and sustain a more inclusive workplace.