This article is a chapter from the BCG report, The Most Innovative Companies 2019: The Rise of AI, Platforms, and Ecosystems .

Innovation, meet automation. This could be the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

In a few short years, artificial intelligence (AI) and its subfield, machine learning (ML), have gone from futuristic vision to near-mainstream capability at many large companies, including in their innovation programs. A quick scan of BCG’s 50 most innovative companies for 2019 shows that top innovators are also AI leaders (Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Netflix, and IBM, for openers) and that many others—including plenty of companies from traditionally nondigital industries (Boeing, Siemens, Marriott, BP, and multiple automakers, for example)—are actively leveraging AI. (See the companion article “ Innovation in 2019 .”)

Like any powerful new technology, AI is the subject of lots of hype. But in this case, real fire lies behind the smoke. The rapid ascent of AI in business is well chronicled in two reports by BCG and MIT Sloan Management Review

The 2018 SMR-BCG report also identified a performance gap associated with this critical new capability, indicating that AI “pioneers” appear to be “pulling further away” from their less aggressive peers. We see a similar pattern with respect to AI in innovation, which carries two key implications. First, AI is not a plug-and-play capability. Second, ML is inductive—that is, machines learn by doing, and they need to be fed large amounts of data to get smarter. Tortoises will have a tough time catching up with hares in this race. But hares can’t afford to become complacent, because AI is truly disruptive and can propel long leaps forward.

What are the leaders doing?

A Strong Correlation

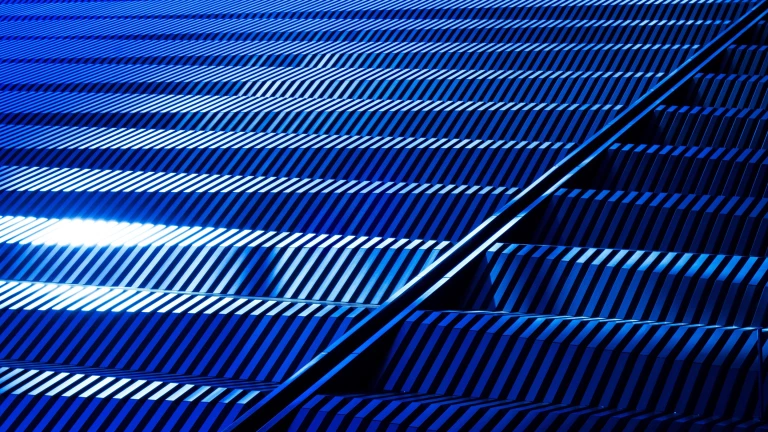

Our most recent innovation survey found a strong correlation between companies that consider themselves strong innovators and those that see themselves as being good at AI. (See Exhibit 1.) About 30% of respondents rate themselves as strong innovators, and about 25% as being better than average at AI. Almost 20% see themselves as both; we call this group “AI leaders.” Nearly 17% of the respondents in our sample view their organizations as being below average on AI; we call this group “AI laggards.” AI leaders are more likely than laggards to consider AI important to their organizations’ future growth (94% versus 56%), which suggests that more than half of laggards will face a widening competitive disadvantage unless they up their AI game.

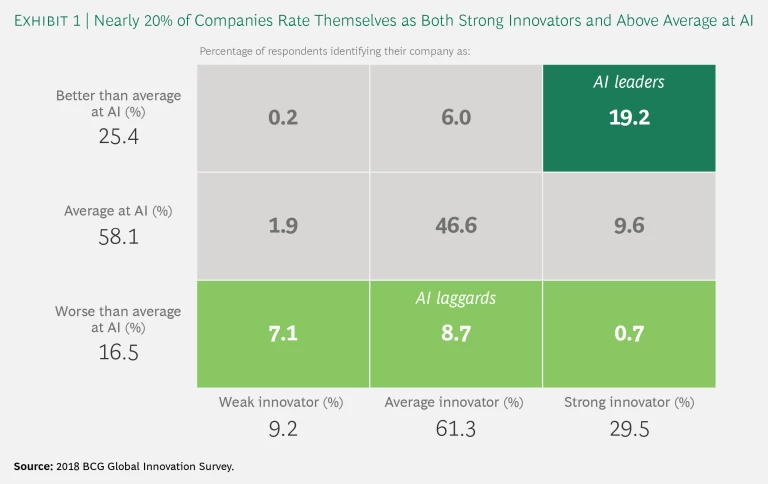

AI leaders tend to see themselves as being good at embracing new technologies such as AI to enhance customer offerings or streamline the development process (89% versus 24%). AI leaders and laggards allocate their spending roughly equally among radical innovation; major new products, services, and internal process changes; and improvement of existing products, services, and processes. But AI leaders are far more likely than laggards to apply big data and advanced analytics throughout the innovation process—from identifying new themes (91% for leaders, 30% for laggards) to informing investment decisions (92% to 27%). (See Exhibit 2.) In addition, by margins of 42% to 19%, and 42% to 24%, respectively, AI leaders are more likely than laggards to be actively pursuing the related avenues of big data and tech platforms.

Where to Focus?

All companies face choices about where to apply resources and where AI might make the most impact. New examples emerge every day. BP (number 46 on the 2019 most innovative list) is using ML to improve its prediction models for oil and gas reservoir recovery. General Motors (number 40) used AI-aided design to reduce the weight of traditionally designed and manufactured parts by 40% while increasing their strength by 20%. Experts predict multiple areas of impact for AI in health care, including improving radiology diagnoses, making medtech devices smart, and identifying new infection patterns. In financial services, Chinese insurer Ping An, a digital native, developed predictive models and leveraged face and voice recognition as foundations of its business. The vice president and chief data scientist at Ant Financial, another Chinese digital financial services leader, told SMR, “AI is being used in almost every corner of Ant’s business. We use it to optimize the business and to generate new products.”

Early AI programs tend to focus on improving operational efficiencies, perhaps because companies can demonstrate success relatively quickly in these areas. The 2018 SMR-BCG report found that many early AI initiatives were pilots or tests designed to solve a particular problem as companies focused their early attention on gathering low-hanging fruit and making moves with near-term impact. Nearly two-thirds of the AI leaders in our study report that their innovation-related use of AI aims to improve internal processes.

As significant as the impact of AI will be on business processes, however, its biggest potential lies in developing new products and services that can evolve into major revenue streams over time. Most AI pioneers in the SMR-BCG study prioritized revenue-enhancing applications, which is where 72% of respondents expect the big AI gains to originate. In our survey, the AI leaders reported much higher percentages of sales driven by AI-enhanced products or services introduced in the last three years: 46% of AI leaders say that 16% or more of sales are AI-generated, compared with only 10% of AI laggards). AI leaders also expect a much greater percentage of sales to come from the introduction of AI-enhanced products or services over the next five years (54% of AI leaders anticipate that 16% or more of sales will come from these sources, compared with 22% of AI laggards).

AI’s biggest potential lies in developing new products and services that can evolve into major revenue streams over time.

Despite ample evidence of impact, AI still garners its share of skepticism, which is one reason that laggards are falling behind. Research by BCG and Google in the consumer products sector found that by applying AI and advanced analytics at scale, consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies can generate more than 10% of revenue growth through multiple means, including more predictive demand forecasting, more relevant local assortments, personalized consumer services and experiences, optimized marketing and promotion ROI, and faster innovation cycles. (See “ Unlocking Growth in CPG with AI and Advanced Analytics ,” BCG article, October 2018.) Yet in our innovation survey, only 23% of CPG respondents said that they believe AI will have the greatest impact on innovation and product development in the industry over the next three to five years, and a similarly modest percentage are actively targeting AI in their innovation programs. Both figures are about 10 percentage points below the cross-industry averages.

AI at Scale

AI forces business executives to deal simultaneously with technology infrastructure and more traditional business issues. Typical IT systems—which consist of data input, a tool, and data output—are relatively easy to modularize, encapsulate, and scale. But AI systems are not so simple. AI algorithms learn by ingesting data, and training data is an integral part of both the AI tool and the overall system. The entanglement is manageable during pilots and isolated uses but becomes exponentially more difficult to address as AI systems interact and build on one another. This leads to what our colleagues have termed the “AI paradox”—the ease of achieving powerful results with AI pilots and the difficulty of replicating those results at scale. (See The Big Leap Toward AI at Scale , BCG Focus, June 2018.)

Talent is a major issue for most organizations. Data scientists and software engineers aren’t the only high-demand personnel. Companies also need people who combine business skills with an understanding of AI. Companies that are moving toward AI-centric innovation processes must consider how the transformation will affect their staffing in terms of skill shortages, job elimination, or both. In pharma, for example, as AI algorithms learn to identify the types of people and conditions best suited for clinical trials—a major process innovation—the need for human involvement in this critical function changes. Banks and other financial services companies are already feeling the impact of voice recognition and credit-scoring systems that use AI technology to automate customer service.

Companies need people who combine business skills with an understanding of AI.

As AI becomes a more critical element of innovation, the talent challenge may widen the gap between strong and weak innovators. After all, Exhibit 1 indicates that more than 65% of strong innovators already see themselves as above average on AI, versus just 2% of weak innovators.

Build Versus Buy

One talent-related issue with immediate impact is the question of whether to build or buy AI capabilities. In our survey, 55% of AI leaders extensively use external vendors for AI projects—36% relying exclusively on them, and 19% relying mostly on them. This approach may help leaders climb the AI curve quickly, since expertise is still in short supply. But because of AI’s heavy reliance on data, companies need to be careful about the agreements they construct with their suppliers and partners. They must protect their ownership of internal data, control how vendors use that data, and ensure their own continuing access to data from outside sources. (See “ The Build-or-Buy Dilemma in AI ,” BCG article, January 2018.)

AI leaders often rely on ecosystems. Digital natives, such as those leading our list of most innovative companies, grew up in ecosystems. Companies such as Amazon, IBM, and Microsoft offer AI capabilities for sale or rent through their cloud-based platforms. Some industrial companies—automakers and aircraft manufacturers, for example—are accustomed to working in broad partnerships of multiple companies, with all of the collaboration and technology and data sharing that these arrangements entail. Others have less experience, but as we explore in a companion article to this piece, the fast-rising importance of technologies such as AI will all but force them to explore such alliances. (See the companion article “ How Collaborative Platforms and Ecosystems Are Changing Innovation .”)

“Alexa, Innovate!”

A fascinating battle for AI-enabled smart-home systems is brewing among Amazon (Alexa), Google (Google Assistant), Apple (Siri), Microsoft (Cortana), and others as each company seeks to capture the biggest share of end-user households for its voice-recognition technology. The battle is a critical early-stage skirmish in a much longer conflict to determine how and for what purposes these systems are used. At this point, streaming music is the most widely used app, but the larger competition may take a generation to decide. The plan appears to be for each company to open its smart-home platform to others, which will innovate actual use cases for consumer testing. Winners can be scaled up quickly and losers tossed aside with equal dispatch.

A fascinating battle for AI-enabled smart-home systems is brewing among major innovators.

Consider Alexa and Google Assistant. These classic platforms enable others to innovate inexpensively on top of them. By opening their platforms to others, Amazon and Google can harness others’ innovations—much as Apple and Google did with their mobile platforms, and as Microsoft did with Windows. The platforms, provided at little or no cost to app developers, take care of the basic plumbing, and the platform owners derive value from having a richer set of services available than they would have had with their own apps alone. In this case, the stakes are high, as use of smart-home systems is expected to increase exponentially as today’s young people grow up talking to, learning from, and coming to depend on these devices.

In China, Baidu uses a similar open-AI platform strategy in the B2B or industrial internet marketplace. Baidu provides access to AI services such as voice and image technology and natural-language processing, which companies are using in such diverse fields as agriculture, manufacturing, and health care, where these innovations have helped reduce the misdiagnosis rate for diabetes-related eye disease to less than 5%. (See “ Get Ready for the Chinese Internet’s Next Chapter ,” BCG article, January 2019.) Open platforms such as these will affect not only how consumers and businesses access AI applications but also how companies build their own AI capabilities.

It’s still the early days in AI. But after years of development, actual use of the technology is catching on fast. Laggards need to get into the game, and leaders need to accelerate their efforts. The platforms offered by Amazon, Google, Baidu, and others may well make some kinds of experimentation and testing and learning easier. But the big issues of access to data and talent won’t get any less challenging over time; if anything, competition for these vital assets will only increase. Companies that hope to rank among the most innovative of the future need to place their AI bets now.