This is the first in a series of articles that look at the actions countries can take to ensure that their labor supply fits demand. In this article we assess government responses to the pandemic and argue that they must make plans now to secure a workforce that is future-ready.

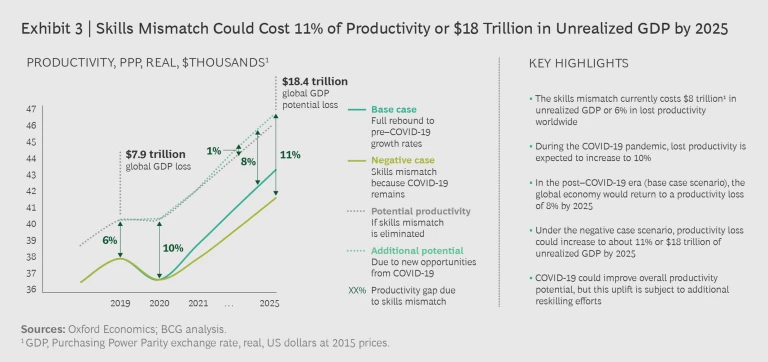

Across the world, an unprecedented labor market shock has governments scrambling to preserve jobs. Their actions are critical—for now. But given the scale of the fallout, they are insufficient. Even before COVID-19 hit, countries faced a skills mismatch (the condition in which supply does not fit demand, whether in an organization, industry, region, or country). The pandemic makes the problem worse, potentially worsening productivity losses from 6% to 11% and resulting in unrealized GDP of $18 trillion by 2025, according to BCG analysis. This means governments must take action now—not only to address the short-term challenges but also to rebuild their human capital for the future.

The impact of the crisis goes beyond economics. It is challenging labor market fundamentals and accelerating digital disruption. It is prompting new questions about the future of work, about how employee mindsets will change, and about what all this means for organizational design. And while governments are focused on flattening the pandemic’s curve, they must also look forward, designing measures for a rapid but sustainable rebound and using the crisis to reimagine their nation’s future.

In doing so, fixing the skills mismatch will be critical. Even before the pandemic hit, this was no simple exercise; it required an understanding of the implications of everything from education and training to social safety nets. However, to craft national skills strategies that can meet future labor force challenges, this knowledge is vital. And for countries that get it right, an informed, strategic approach could accelerate productivity growth and enhance the future-readiness of their human capital.

The Response to Labor Market Shocks

It is hard to overestimate the dramatic changes the COVID-19 crisis has imposed on the global labor force landscape. The sheer numbers make for shocking reading. In 2020, more than 1.9 billion people (over half of the global workforce) will be affected by layoffs or reduced working hours. BCG analysis finds that, with one in six people likely to lose their job in the next two to three months, the unemployment rate could exceed 17% in the near term. Projected labor income losses are $3.4 trillion, according to the UN International Labor Organization (ILO).

The impact will vary widely among different sectors, with those directly affected by lockdown measures the hardest hit. BCG expects more than 80% of layoffs worldwide to come from the nonfood retail sector, manufacturing, accommodation and catering, and travel and construction.

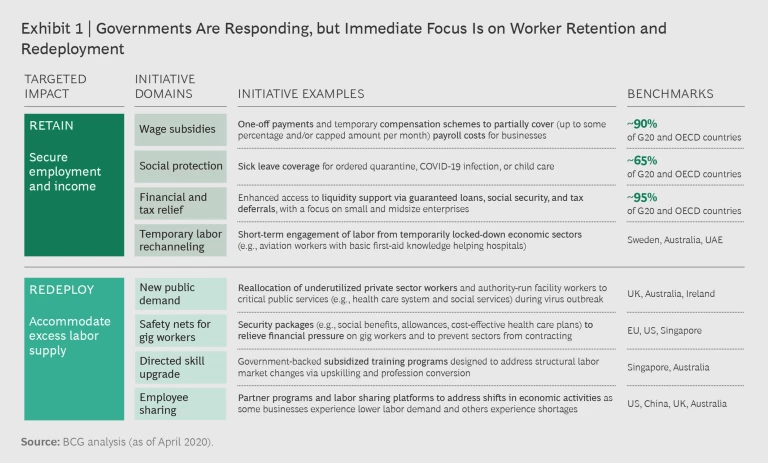

To secure income and employment and prevent further reductions in the labor supply, governments are responding swiftly. (See Exhibit 1.) Some measures come in the form of loans or financial and tax relief. Others include short-term redeployments, one-off payments, temporary compensation schemes to help businesses cover payroll costs, and sick leave coverage for those ordered to self-quarantine, those with COVID-19 infection, and those who need to care for children.

Redeployment measures include temporarily reallocating underused workers, mostly from the private sector, to roles in critical public services such as health care and social services. Governments are also providing safety nets for gig workers, subsidized training programs to address structural labor market changes, and employee-sharing schemes that enable businesses with falling labor demand to provide workers for businesses experiencing shortages.

The pandemic has already triggered long-lasting structural changes that will affect up to 1.5 billion jobs within the next decade.

We expect global unemployment to start to rebalance by the end of 2020. However, the pandemic has already triggered long-lasting structural changes—flexible and remote working arrangements, for example, and accelerated automation—that will affect up to 1.5 billion jobs within the next decade. And while automation will put at risk 12% of current jobs by 2030, some 30% of jobs will require completely new skills. Governments certainly need to move aggressively to meet the crisis in the short term, but equally important will be what they put in place now to secure the long-term strength of their human capital.

A Strategic Approach for a New Work Landscape

The measures we see governments taking now are necessary in the short and medium terms, but the far-reaching effects of the pandemic on the fundamentals of the global labor market demand holistic strategies that go beyond crisis-response initiatives.

The pandemic has transformed working modes. With the ILO estimating that 81% of the global labor force is engaged in a work-from-home experiment, flexible and remote arrangements are likely to become the new normal. In the wake of the crisis, some 75% of global businesses plan to shift at least 5% of employees who previously worked on site to permanently remote positions, according to Gartner. BCG expects that more than 10% of workers are likely to switch to permanently remote work arrangements (for office employees, this portion could be as high as 30%).

The sudden need to work remotely online has triggered the acquisition of digital skills at scale, offering professionals new opportunities for both enhanced careers and increased income. In the UK, for example, the remuneration rates for roles that require digital skills are 29% higher than those for positions that do not require such skills, according to Burning Glass Technologies.

We expect that more than 10% of workers are likely to switch to permanently remote work arrangements.

The organization of work is likely to change, too. Some of this represents an acceleration of trends already in motion. For example, a 2018 Gallup report found that 36% of US workers were part of the gig economy. And a 2017 report from Upwork and Freelancers Union predicted that freelancers would become the majority of the US workforce by 2027. Meanwhile, the digital transformation will see a shift of focus from procedures to results. Simplified labor agreements and contract automation will make many roles, such as those in administrative functions, obsolete.

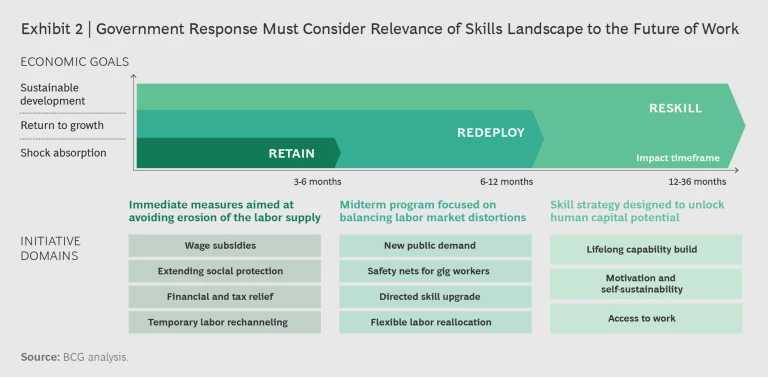

All this demands a strategic response based on holistic thinking about the relevance of the skills landscape to the future of work. While the measures that governments must take will need to accommodate developments across three distinct time horizons, all measures—both short- and long-term—need to be developed and implemented now, and with equal urgency. (See Exhibit 2.) Countries that emerge from the outbreak earlier than others will of course need to act faster on certain labor market initiatives.

To prevent erosion of the labor supply, the first three to six months will require a focus on retaining workers, including use of some of the same measures that governments are currently implementing—wage subsidies and extended social protections, financial and tax relief, and temporary labor redeployment.

The midterm focus (starting now but with a longer-term implementation horizon) will require a balancing of the labor market or redeployment of the available labor force to minimize unemployment. Measures to accomplish this include safety nets for gig workers, skills upgrades, and flexible labor reallocation.

Now is also the time to start preparing for the post-coronavirus future (a 24-month period, but with planning starting immediately) by adopting a broad-based strategy in which reskilling is the overarching imperative. This means giving the entire population access to lifelong learning opportunities and ensuring that workers are motivated and able to sustain their own continuous professional development and that access to work opportunities is universal and equitable.

Addressing a Wider Skills Mismatch

None of this will be easy. The skills mismatch was a problem for governments even before COVID-19 arrived. It affected two out of five employees in OECD countries, prevented millions of people from fulfilling their potential, and created severe labor productivity losses. BCG analysis shows that the mismatch effectively imposed a 6% annual “tax” on the global economy and that now, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation could cost 11% in terms of productivity or $18 trillion in unrealized GDP by 2025. (See Exhibit 3.)

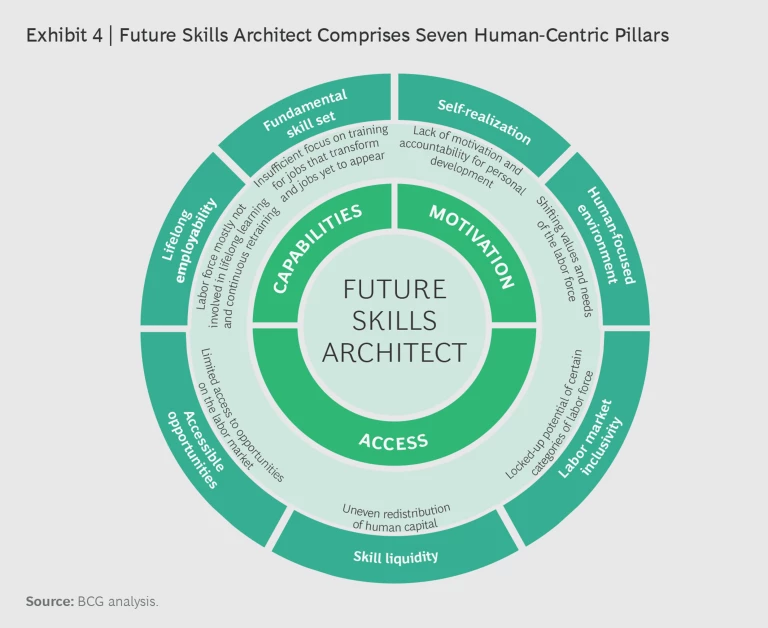

However, there are ways to avoid these harsh economic costs. To fix the skills mismatch, governments must address seven key challenges across the three pillars that underpin a robust and productive workforce: capabilities (fundamental skill sets and lifelong employability), motivation (self-realization and a human-centric approach that treats people as equal partners in shaping society and the economy), and access (available opportunities, skills liquidity, and labor market inclusivity).

To help governments navigate the challenges and develop appropriate solutions, BCG recommends a three-step Future Skills Architect (FSA) methodology that provides insights on different aspects of the skills mismatch and offers a solutions library. For all seven of the challenges, the FSA helps quantify the problems, benchmark the solutions, and create policies. (See Exhibit 4.)

Knowledge Is Power

Armed with a deeper understanding of the nature of the skills mismatch and how it is rooted in the seven key challenges, governments can design and apply tailored measures that are appropriate for their economic and workforce agendas, adopting labor, education, and skilling strategies that reduce their particular skills mismatch. Three steps are involved:

- Conducting a health check, which provides insights on how effective a country is in addressing its skills mismatch challenges and helps identify appropriate actions

- Benchmarking to determine what comparable countries are doing, what practical solutions they are using to meet each of the seven key challenges, and why these measures are proving successful in solving their skills mismatch

- Adopting solutions, which involves both how a country can apply solutions that have proven successful in other countries and how it can develop its own solutions

The Future Skills Architect can help advance a range of different country agendas, from productivity and labor force participation to meeting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Addressing the structural changes that the COVID-19 crisis has brought to the world of work is a matter of urgency for all governments. If countries are to rebuild their economies, they must address the disparities between the skills they have available and those required by businesses and the broader economy.

In the post-crisis world, governments that can adjust their skills landscapes and strengthen the future-readiness of their human capital will be able to unlock labor market opportunities and demonstrate that they can be leaders rather than followers. And they can help others learn from their example, working to unlock significant productivity and economic potential.

In the second article in this series, with country-specific examples from developed and emerging economies, we explore in greater detail how the FSA methodology works and how best to get started.