Conventional wisdom suggests that when it comes to innovation, small companies have the edge. They are quick and nimble. They have no legacy organizations, technology, or infrastructure to hold them back. Because they are often privately owned, they can play for the longer term. Big companies, by contrast, are weighed down by internal bureaucracy, bound by out-of-date systems and ways of working, and if publicly traded, too focused on the next quarter’s earnings to think about the longer term.

But even before the crisis, the data suggested a more nuanced picture. While smaller companies’ scale makes coordination easier—and helps ensure that they stay closer to customers—our research found that the innovation success rates of smaller companies were not higher in any statistically significant way than those of larger ones. And today, given the greater ability of larger companies to fund investments from their own cash flows, some of them may actually have an edge.

Of course, if size is not an impediment to innovation, it stops being an excuse for underperformance. After all, as we show in a companion article in this year’s report, the most innovative companies in BCG’s annual listing have been getting larger. So what distinguishes the large companies that are innovation winners from the rest?

The Big Engines That Can

Large companies face a few common obstacles. The top two issues cited by all large firms in our 2020 innovation survey are a lack of discipline in resource allocation, including insufficient rigor in cutting questionable projects while putting muscle behind those with promise (31%), and the difficulty of uniting the organization behind the innovation strategy (27%).

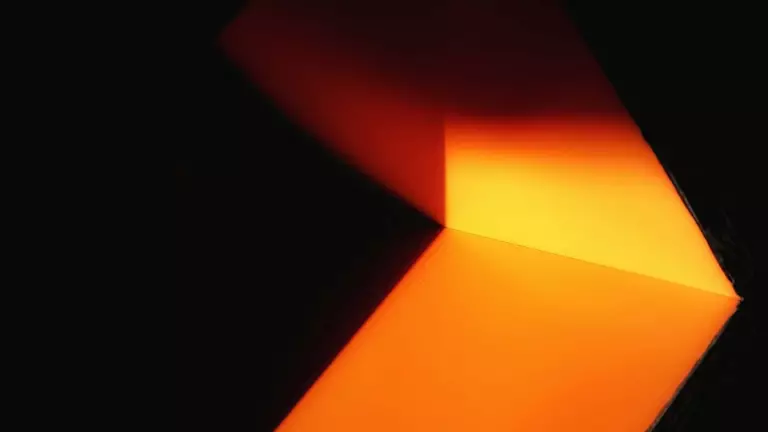

But not all large companies are alike. More than 40% of the big companies (defined as $1 billion or more in revenue) in our 2020 sample overcome these two key obstacles. They fall into the innovation leaders category—that is, they generate a larger percentage of sales from products or services launched within the past three years than their industry median. This compares with on average 50% of the smaller firms surveyed. (See Exhibit 1.) So, smaller companies are more likely to outperform the large firms, but the difference is small in magnitude and not statistically significant.

More Bang for the Buck

Innovation leaders appear to be remarkably alike, regardless of size. Smaller leaders make investments in innovation as a percentage of sales at a similar level as bigger companies. They are equivalent in speed to market and achieve comparable returns. The real distinctions emerge when we look at what distinguishes large leaders from other large firms.

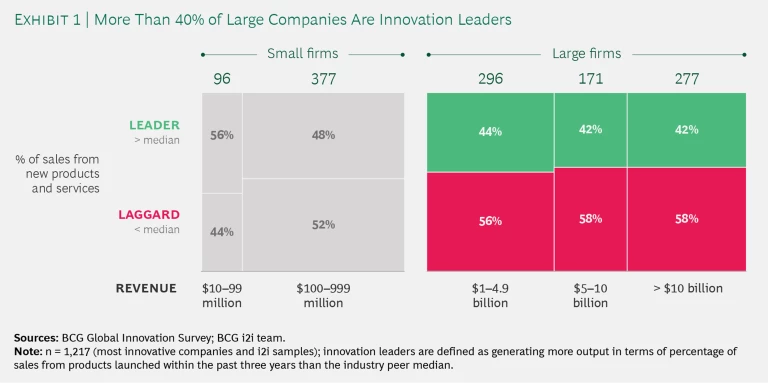

Large innovators that outperform their big-company peers put more money behind their innovation programs—1.4 times more as a percentage of sales—and they get far greater payoffs: four times as much as a percentage of sales. (See Exhibit 2.) Surprisingly, they also take time to get things right, with large leaders reporting average times to market for innovation outside their core that are up to five months longer than the times for others.

Overcoming Barriers

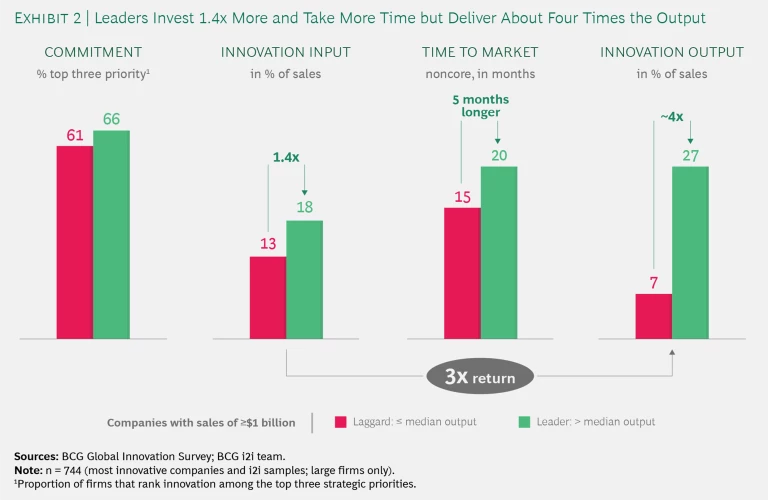

So among the larger innovators, what are the key differences between the leaders and the laggards? To our surprise, culture does not appear to be one of them. In fact, the cultures of large companies, both leaders and laggards, look very similar. (See Exhibit 3.) Granted, an innovation culture is notoriously hard to describe or assess. Still, the data suggests culture may not be a precondition for, but rather have a correlation with—or even be an outcome of—innovation success.

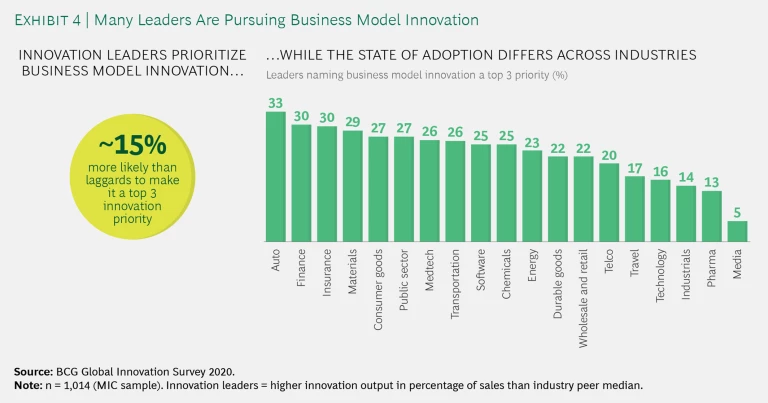

Leading large innovators pursue different priorities and more carefully design their innovation systems for impact. Laggards must first put a lot of attention into fixing the basics: building new and critical incubation or development skills, gaining leadership support, and establishing strategic clarity on the direction of innovation efforts. Leaders seem to have the luxury to address higher-order issues, however, such as filling gaps in product-market fit and building a stable of scalable external partners. Leaders are also about 15% more likely to prioritize business model innovation although not uniformly across industries. (See Exhibit 4.) Innovation at the business model level—to defend existing profit engines, to imagine entirely new offerings in response to emerging customer needs, or to adapt current business models to ongoing shifts in the business environment—can provide an important edge, particularly in turbulent environments.

These differences do not suggest that some strategic choices are better than others. They do spotlight the importance of having an internally consistent systematic approach to innovation.

Designing a Winning Innovation System

Deeper analysis of the differences between leaders and laggards in the same industry (as well as BCG’s client experience) points to leaders expanding their advantage in five aspects of their innovation systems. These are talent, ambition, governance, funnel management, and project management.

Our benchmarking database reveals that achieving just one level of improvement on our five-point maturity scale in any one of these five aspects can result in an increase in innovation output (the percentage of sales from products, services, or business models introduced in the past three years) of 0.5 to 0.8 percentage points. A one-level improvement in all five dimensions raises innovation output by 3.4 points—a big yet very much achievable number for any large company.

Inspiring Ambition. Leaders align their innovation ambition with corporate strategy and communicate the connection. The organization has a clear, shared understanding of what it means by “innovation.” Leaders also back their ambition with resource commitments of capital, operating budgets, and staff, as well as top management support. We recently helped a large energy company set its innovation ambition in an iterative process that took into account organic growth expectations and the projected shrinking size of the running business. On that basis, we derived the target growth from innovation and then validated this target with bottom-up growth potentials from different market segments. We then further assessed the resulting ambition against the availability of funds and talent.

One Steering System. Leaders increase their odds of success by establishing good-governance practices and regularly adjusting them as needs change. For example, most large companies now have a varied set of ecosystem partners and vehicles—including internal incubators, venture funds, and accelerators —to accelerate innovation by complementing their in-house development efforts. In practice, these vehicles often overlap in scope, undermining their effectiveness. We observed this dynamic at a global manufacturing company that had various vehicles with overlapping mandates, creating competitive tensions and leading to disconnects with the core business. The company corrected these overlaps by setting up a coherent steering system with specific roles and success metrics for each vehicle.

Talent First. Leaders work toward making their innovation teams go-to destinations for internal and external talent. They devote resources to attracting, training, and retaining the best people they can find—often prioritizing those with entrepreneurial experience. Yet what really drives performance, in our view, is their ability to allocate their best internal talent to innovation teams. One medtech company elevated the role of head of R&D to chief technology officer (a board-level position), trained technical managers in business so that they could become product owners capable of leading cross-functional teams, and now delivers more new digitally enabled solutions than ever.

Portfolio Mindset. Leaders pay close attention to the shape and quality of their innovation funnel—and the processes to manage it. Not surprisingly, leaders tend to have broader funnels: they have the capacity to generate more potentially valuable ideas and convert their best ideas into scalable products or services. Funnel management ultimately comes down to the quality of decision making in a few critical go or no-go decisions, as well as the ability to take both a project and a portfolio perspective at the same time. Winners create the context for better decision making by establishing a focused set of tools and criteria for making the right call, ensuring the ideal balance between hands-off and hands-on involvement, and setting the right incentives, such as not penalizing innovation teams for flagging issues or even recommending a late project pivot.

What’s more, leaders consistently run postmortem analyses to make sure that they learn from mistakes. The best innovators do this not only for failed projects but also for funding decisions that, with the benefit of hindsight, look like false positives or false negatives, to ensure better-quality decision making going forward.

Empowered Teams. Ultimately, the innovation success of a company lives and dies with the quality of its innovation teams. Good teams are small (they adhere to Jeff Bezos’s two-pizza rule) yet functionally diverse, that is, they are staffed with a mix of product managers, engineers, and designers. They typically combine data-driven (patent scanning, for example) and human-centric (such as ethnographic) methods to find solutions to problems that add value for customers.

These teams need a healthy degree of autonomy, embedded in a supportive governance framework. Ideally, they are led by a strong product owner whose top task is to maximize the desirability and viability of the innovation while keeping it technically feasible to deliver in an acceptable time and at an acceptable cost. Incentives matter. Less successful companies tend to manage teams on delivery against expected outputs, while leaders reward high-quality outcomes. A high-quality outcome could be a resounding in-market success but also the early demise of an initially promising but ultimately doomed idea.

We recently assisted a large automotive company in improving the elements of its innovation system. Early idea generation at the company now starts by pairing deep technology and regulatory foresight with customer centricity. In cross-functional ideation sessions focused on anticipated future market opportunities, teams iteratively refine their ideas by drawing up a mockup product-launch press release. These teams address technical, market, and business risks by running an open backlog of implicit, to-be-validated beliefs. Through such methodical testing, the biggest innovation risks are addressed first, greatly improving the odds of an ultimate in-market success. Senior managers set an inspiring yet achievable ambition. They make decisions on the portfolio and funnel of projects every two months, ensuring thoughtful and timely decisions well informed by their proximity to the action.

Being a great innovator is not just about embracing best practices such as the ones detailed above, although doing that is table stakes. It’s also about spotting changes in the technology or regulatory environment, in markets, and in social norms, and then understanding which doors these changes open and which they shut. In many ways, the most successful companies see innovation as a learning journey in which the destination shifts in response to changing travel conditions. As it turns out, the real innovation challenge for large companies isn’t achieving one great success—

When It Comes to Innovation, Once Is Not Enough

.