The Biodiversity Challenge

The damage we are inflicting on species and ecosystems is so extensive and profound that scientists now believe we are witnessing Earth’s sixth mass extinction event—the last one marked the end of the dinosaurs.

—David Attenborough

Two facts about biodiversity are not up for debate. The first is widely known, the second less so.

Fact number one: biodiversity—the level of diversity in the natural world, at the ecosystem, species, and genetic levels—is being destroyed at an alarming rate. Fact number two: biodiversity loss has massive implications for business.

BCG set out to study the biodiversity crisis, understand the business role, and determine how companies should respond. Among our findings:

- Biodiversity creates significant economic value in the form of such ecosystem services as food provisioning , carbon storage, and water and air filtration, which are worth more than $150 trillion annually—about twice the world’s GDP—according to academic research and BCG analysis.

- Five primary pressures—land-use and sea-use change, direct overexploitation of natural resources, climate change, pollution, and the spread of invasive species—are causing steep biodiversity loss. Already, the decline in ecosystem functionality costs the global economy more than $5 trillion a year in the form of lost natural services.

- Many business activities, especially activities related to resource extraction and cultivation, contribute to the pressures driving biodiversity loss. The operations of four major value chains—food, energy, infrastructure, and fashion—currently drive more than 90% of man-made pressure on biodiversity.

As ecosystems decline, business faces significant risks, including higher raw material costs and a backlash from consumers and investors. But the crisis also creates real opportunity. Companies that act to support biodiversity can develop powerful new offerings and business models, improve the attractiveness of existing offerings, and lower operating costs.

Understanding Biodiversity

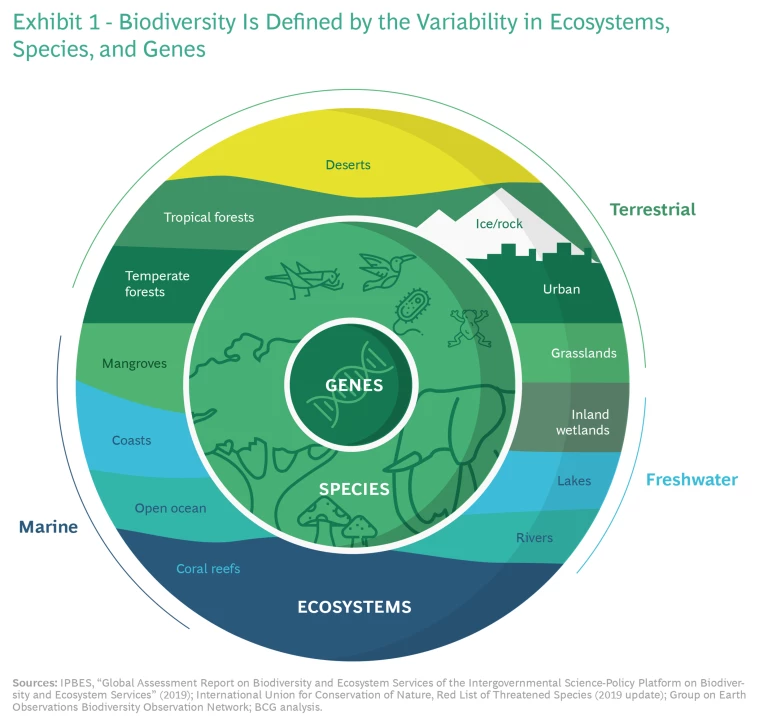

Biodiversity reflects the range and variety of life on Earth—and thus the health and resilience of nature—at three levels (see Exhibit

1

):

- Ecosystems. Diversity at the level of entire ecosystems—for example, wetlands, grasslands, or forests—is a function of the size of the intact ecosystem area, the magnitude of its biomass, and its ability to provide ecosystem services such as water regulation or air purification.

- Species. The variation in species, including plants, animals, and microorganisms, involves both richness (number of species) and abundance (population for each species) within each ecosystem, as well as the distribution of species across ecosystems.

- Genes. Genetic variability is essential to species’ ability to adapt to environmental changes and their resilience to external threats such as diseases.

The Economic Value of Biodiversity

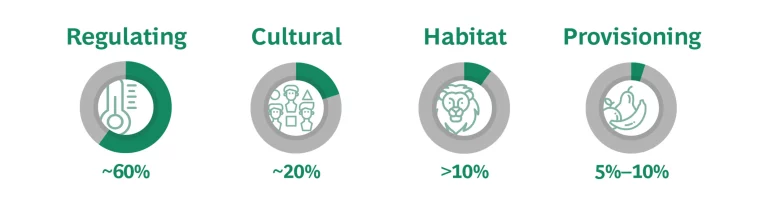

The delicate balance and interplay of ecosystems, species, and genes produce services that are vital to the functioning of society and the modern economy and, therefore, create sizable economic value. These ecosystem services fall into four primary categories: regulating, cultural, habitat, and provisioning.

- Regulating. Natural ecosystems provide multiple services that are essential to environmental stability. Among them are climate regulation (through carbon sequestration), water storage and filtration, air purification, and control of biological disturbances such as diseases.

- Cultural. Natural ecosystems serve diverse spiritual, heritage, educational, and recreational functions.

- Habitat. Ecosystems provide space for plant, animal, and microorganism species to live, migrate, and procreate, and they support the formation of fertile soil, which is vital for the survival of plants and other organisms and for food production.

- Provisioning. This category captures the share of the value of nature-based products such as food, timber, and medicinal inputs that is created within ecosystems.

On the basis of research from the TEEB initiative, we estimate that the combined annual value of these four ecosystem services is more than $150 trillion, almost twice the size of global GDP.

The Drivers and Dangers of Biodiversity Loss

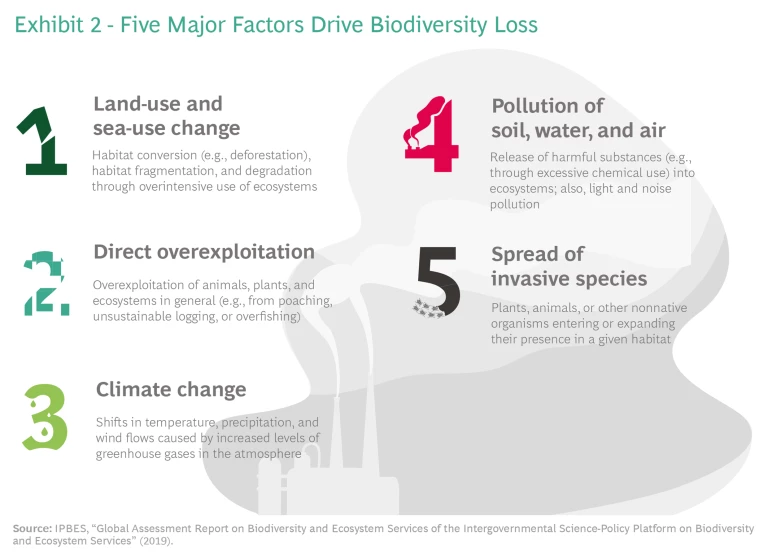

According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), five pressures are primarily responsible for driving biodiversity loss (see Exhibit 2):

- Land-Use and Sea-Use Change. This category of pressure is the single largest factor driving biodiversity loss; it comprises the conversion, modification, and gradual degradation of natural ecosystems.

- Direct Overexploitation of Natural Resources. Direct overexploitation—the extraction of more animals, plants, and other resources than can be naturally restored—is the second-largest factor in biodiversity loss.

- Climate Change. Climate change indirectly catalyzes and accelerates other biodiversity pressures by spurring ecosystem and species decline. These effects are evident today in rising ocean acidification and desertification, melting ice landscapes, and catastrophic events such as floods, wildfires, and droughts. That degradation in turn releases carbon stored in the ecosystems, contributing to further climate change.

- Pollution of Soil, Water, and Air. Pollution can significantly harm ecosystem functionality by changing the composition (nutrients, acidity, and oxygen levels) of soils, waterways, and the ocean.

- Spread of Invasive Species. Invasive species are nonnative plants, animals, or other organisms that enter alternative habitats. Infiltrating areas in large numbers, they may destabilize entire ecosystems by competing for food, trampling soils, or crossbreeding with local species.

The Burning Platform for Business

Companies need to move aggressively in support of biodiversity. Forward-looking players understand that continued biodiversity loss creates significant risks for their business—and that as an early mover they stand to benefit from new business opportunities and improved standing with customers and investors. (See Exhibit 3.)

Risks. Businesses face three main biodiversity-related risks:

- Given that more than half of the world’s GDP depends heavily on functioning natural ecosystems, according to the WEF, the decline of natural ecosystems threatens to disrupt many important supply chains. Food producers, for example, could face higher costs as natural pollinators vanish. But the economic impact of a decline of natural regulatory functions and a resulting increase in major disturbances such as flooding will extend well beyond industries that rely on natural inputs for their production.

- Pressure on business from governmental regulations related to biodiversity is increasing and may impose significant additional costs in the future.

- Companies that fail to address the negative impact their operations have on biodiversity put themselves at risk of eroding the goodwill of their customers and other stakeholders and, as a result, having a diminished social license to operate.

Opportunities. Companies that lead on biodiversity will have significant opportunities to benefit from these efforts:

- They will position themselves to enter profitable new markets by developing valuable new products, services, and entire business models.

- They can improve their value proposition and their brand by responding to public demand for sustainability.

- They will have better access to capital and potential operational synergies, including through reductions in raw material and energy costs.

Business Activities and Value Chains Contributing to Biodiversity Loss

Biodiversity impacts arise all along the economic value chain: The largest impact results from resource extraction and cultivation activities, which account for more than 60% of overall pressure. But resource conversion and manufacturing, services such as transportation and mobility, and consumption—including after-life treatment—have a considerable biodiversity footprint, too.

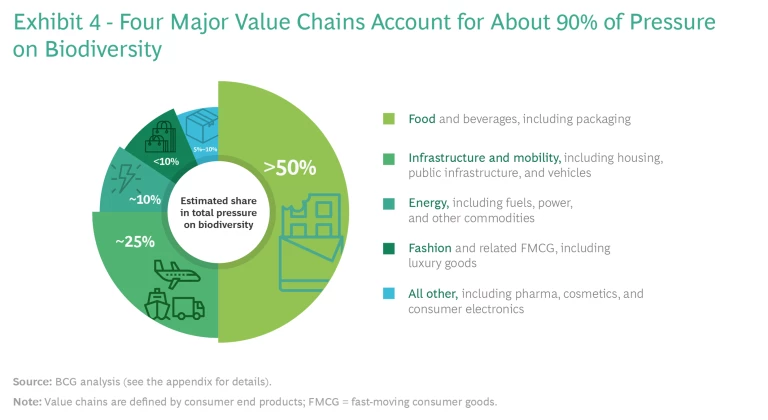

These four categories of activities occur in virtually every major value chain in the global economy. Four value chains are responsible for roughly 90% of biodiversity loss (see Exhibit 4):

- Food. Biodiversity is critically important to the food value chain, and yet that value chain drives more than 50% of man-made pressure on biodiversity. Common issues include agriculture-related forest conversion , overfishing, and generation of plastic waste .

- Infrastructure and Mobility. Housing, public buildings, technical infrastructure, transportation infrastructure, and vehicles are responsible for about 25% of human pressure on biodiversity. Contributing factors include land use for and pollution from the extraction and conversion of raw materials, as well as ecosystem conversion and modification during infrastructure construction.

- Energy. The energy value chain accounts for an estimated 10% of man-made pressure on biodiversity, largely due to pollution and greenhouse gas emissions that occur during the extraction and conversion of energy carriers and their use in power generation and mobility.

- Fashion. Fashion depends to a great extent on biodiversity. Roughly 25% of textile fibers and more than 50% of apparel are cotton based. And like the food value chain, the fashion value chain has a large biodiversity footprint, including effects related to farming and raw materials extraction for natural and synthetic fiber production, fabric production, and consumer usage and disposal.

Building a Biodiversity-Positive Business

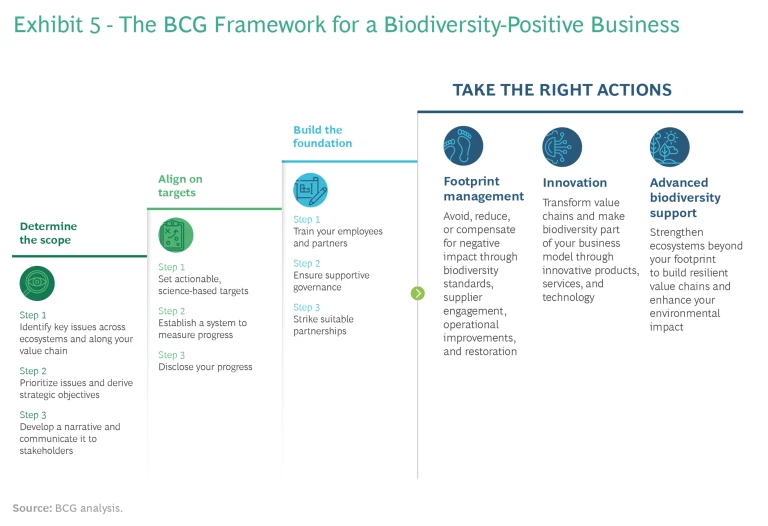

To arrest or reverse large-scale biodiversity loss, companies across value chains must transform their businesses. We have developed a four-stage approach for companies that aspire to become biodiversity-positive businesses. (See Exhibit 5.)

Determine the Scope of Action

To determine the appropriate scope of action, a company should take three concrete steps:

- Step 1: Identify key issues. This identification process should include the company’s own sites of operation and those of its suppliers of raw materials, components, energy, or services —and it should assess the impact of how consumers use and dispose of the company’s products and services. For each of those categories, the company should consider three factors. First, which ecosystems are concerned? Second, what are the pressures, and what is the company’s role in causing them? Third, which issues are most urgent? The answer to the last question will depend on several things, including the state of the ecosystems in question and the magnitude of pressure on them, the importance of those ecosystems to society in general and to the company’s value chain in particular, and the company’s contribution to the pressures (its biodiversity footprint).

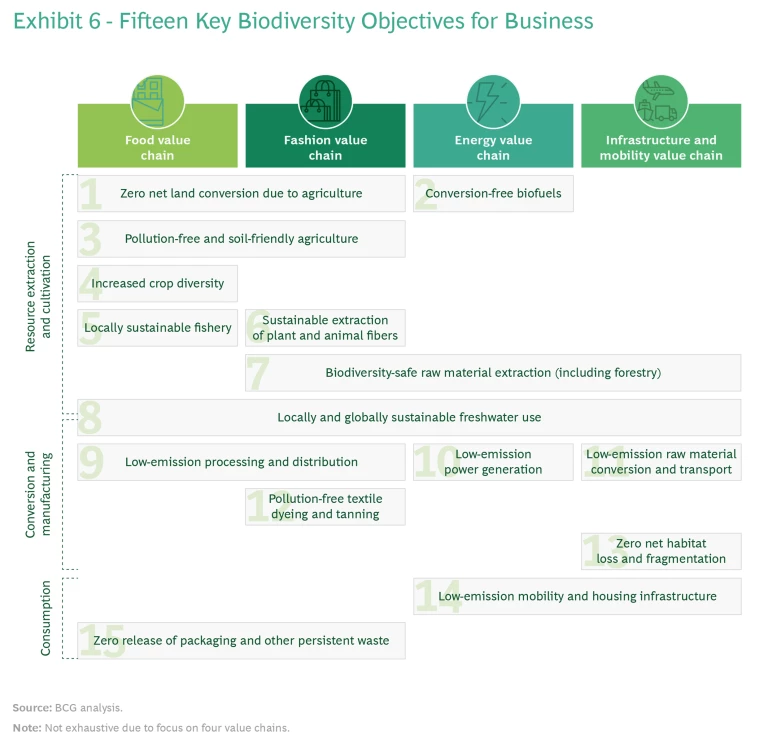

- Step 2: Prioritize issues and derive strategic objectives. In analyzing each issue, the company should apply two criteria: the materiality of the issue and the degree of control the company has over it. After prioritizing its major biodiversity issues, the company should translate them into strategic objectives. Our research indicates that 15 objectives could significantly move the needle toward greater preservation of biodiversity. (See Exhibit 6.)

- Step 3: Develop and communicate a narrative. The company should create a narrative to guide its biodiversity action. As the company takes steps to reduce its negative impact on biodiversity, it should disseminate the narrative both within the organization and to outside stakeholders such as consumers, investors, and regulators.

Align on Targets

To integrate its strategic objectives into operations, a company must take three steps:

- Step 1: Set actionable, science-based targets. Formulating detailed targets will enable the company to select specific local initiatives and evaluate its progress toward them. The Science Based Targets Network is currently developing comprehensive guidance for target setting.

- Step 2: Establish a system to measure progress. The company should establish a system to help it develop locally suitable initiatives that address high-priority issues and to track the progress of those initiatives in terms of inputs, direct outputs, medium-term outcomes, and long-term impact on ecosystem health.

- Step 3: Disclose your progress. The company should publicly disclose where it stands relative to the targets it has set, both at the start of its efforts and over time as it progresses toward its objectives.

Build the Foundation for Success

Companies should take three steps to enhance and refine their existing sustainability capabilities:

- Educate employees and business partners about the importance of biodiversity, and train them to integrate biodiversity concerns into their decision making.

- Integrate biodiversity targets with existing governance mechanisms to ensure that those targets receive the same attention as financial KPIs.

- Pursue partnerships to enhance their capabilities and overcome cost and technology barriers by pooling resources, gaining access to technology, and sharing knowledge.

Take the Right Actions

Companies can take action in three areas to build a biodiversity-positive business:

- Footprint Management. Companies should address footprint management goals along a spectrum known as the mitigation hierarchy. First, they should try to avoid any interference with biodiversity. Second, where avoiding interference is impossible, they should reduce the negative impact. Third, they should seek ways to compensate for such impact by restoring ecosystems or supporting their natural regeneration. This includes adopting biodiversity-safe operating standards, setting sourcing standards and supporting suppliers in meeting them, improving process efficiency, embracing biodiversity-positive land use, and driving ecosystem restoration and regeneration. Luxury brand company Kering supports suppliers through its South Gobi Cashmere Project to preserve rangeland biodiversity in Mongolia. The initiative educates and works with goat farmers to help them adopt practices such as optimized stocking rates and rotational grazing to support soil health, and it uses satellite monitoring to provide them with data on pasture quality and wildlife protection. For its part, Veracel, an operation of forestry company Stora Enso in Brazil, deploys comprehensive biodiversity management practices, including controlled burning, leaving deadwood in place in forests, and maintaining a diverse forest structure .

- Innovation. By leveraging new technology or through other means, companies can develop products and services that cause less ecosystem disruption, depend less on natural resources, enable others to adopt biodiversity-friendly practices, or facilitate the natural development of ecosystems. Some seed producers, for example, are breeding crops that are more resistant to pests and have an improved uptake of fertilizers, thereby reducing the need for crop-protection chemicals. Packaging companies are developing new biodegradable products, and fashion players are studying how to phase out the use of toxic materials and mitigate the volume of microfibers that find their way into natural ecosystems.

- Advanced Biodiversity Support. Companies can work to support biodiversity beyond their core business by assuming a stewardship role for specific landscapes and seascapes, sharing knowledge and data, providing funding, and driving collective action. Retailer Marks & Spencer has successfully brought together a broad range of stakeholders in its work with the WWF to address water scarcity in multiple regions, including a project to improve water governance and drive sustainable strawberry farming in Spain. And companies from different industries have united in the UK Plastics Pact to raise awareness of the environmental impact of plastic waste and to promote a more circular plastic economy.

Some companies will want to move in one or two of these areas, while others will have opportunities in all three.

Because of the position they hold in their value chain, some companies can take actions that have far-reaching impact. In the food value chain, for example, suppliers of machinery and agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilizer are in a strategic position to influence the activities of farmers and fisheries. Regardless of their value chain position, however, companies must move beyond mere declarations of intent and actually deliver meaningful and locally measurable benefits for ecosystems.

The authors thank Mario Vaupel for his invaluable contributions to the research, conceptual development, and writing of this report.