When it comes to creating an inclusive work environment, time is of the essence. The first year of employment is critical for LGBTQ+ employees, as most workers come out either during their first 12 months on the job or not at all, according to the Out@Work Barometer, a global survey by BCG of approximately 8,800 people in 19

For companies, creating an environment in which employees feel comfortable sharing their identity carries significant rewards. Our survey found that LGBTQ+ employees who are out at work are more empowered and feel more comfortable about speaking up, being themselves, and building close friendships at the office. That insight helps explain why research by BCG and others has found that inclusive cultures are associated with reduced employee turnover and more successful teaming.

The good news is that companies can help ensure that employees feel comfortable bringing their authentic selves to work from day one. The key is to foster diversity, equity, and inclusion at all stages of the employee journey, especially during recruiting and onboarding and in the day-to-day environment. Such actions signal that the company is walking the walk of building an inclusive culture.

The Important First Year

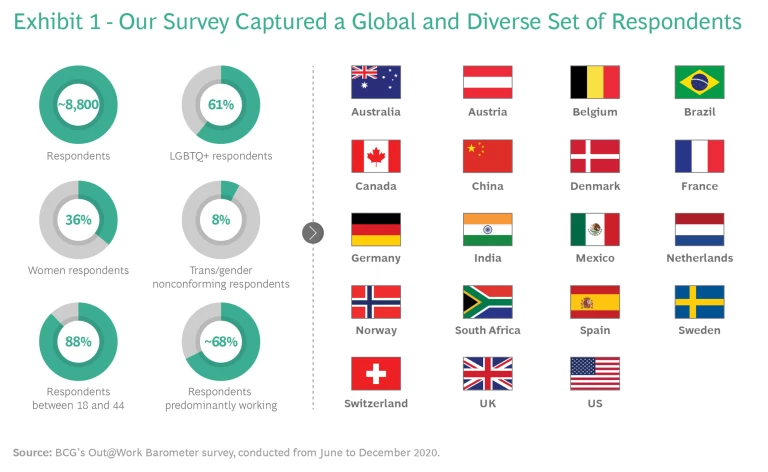

To understand the experience of LGBTQ+ people in the workplace, we cast a wide net, surveying more than 8,800 people. (See Exhibit 1.)

Our sample was not representative of the overall population or all industries, however; rather, it was skewed toward employees who worked in corporate settings and possessed relatively high levels of education. Respondents tended to work for companies that had relatively advanced LGBTQ+ policies and programs. Our survey covered trans and gender nonconforming employees as well, shedding light on significant challenges that members of this group face. (For additional details about the survey methodology we used, see the “Our Methodology.”)

Our Methodology

Our survey drew responses from approximately 8,800 respondents in 19 countries—Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Germany, India, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US—with a targeted and focused outreach to the LGBTQ+ community. We also included a control group of non-LGBTQ+ individuals, sourced through the same media, and administered their survey results through the same channels.

Key facts about our overall pool of respondents:

- 61% self-identify as LGBTQ+.

- 36% self-identify as women.

- 8% self-identify as trans or gender nonconforming.

- 88% are in the age range of 18 to 44 years old.

- Approximately 68% are currently working more or less full time.

- The modal sample size of LGBTQ+ respondents across the 19 countries was 125.

When reporting an average across countries, we aggregated the data by country and then took a simple (unweighted) average across countries. Except where otherwise noted, in aggregating results, we excluded one or more countries from the analysis if fewer than 80 LGBTQ+ respondents from each such country answered a particular question.

In some specific cases—for example, in the sidebars “The Reality for Trans and Gender Nonconforming Employees” and “The Challenges for LBTQ+ Women”—where the sample sizes from some individual countries were not statistically significant, we aggregated responses into a single global pool, which we then adjusted to ensure that countries with a high response rate did not skew the global average reported in these sidebars.

Across the countries included in our survey, LGBTQ+ employees were most likely to be out with friends (average 92% across countries), but this percentage dropped consistently in each country with respect to family (82%), colleagues (76%), and clients (45%). The percentage of respondents who were out with respect to clients was consistently the lowest in the survey, country by country. In Denmark, for instance, 95% of respondents said they were out to friends, 88% to family, and 80% to colleagues, but just 38% to clients.

Although this trend held true in all of the countries we surveyed, respondents in Australia, the Netherlands, and the US expressed a relatively high level of comfort with being out to clients, as 65% to 75% of respondents stated that they were out in client settings. At the other extreme, just 16% to 22% respondents in India and China reported being out to clients.

The survey also made clear that coming out is not a singular event but rather a journey defined by daily decisions and interactions. Even after making the initial leap to share their identity at work, many LGBTQ+ individuals choose to cover up that information at times. Across the countries in our survey, about one-fourth of those who described themselves as mostly out at work said that they would on occasion lie, omit details, or avoid answering questions about their sexual orientation.

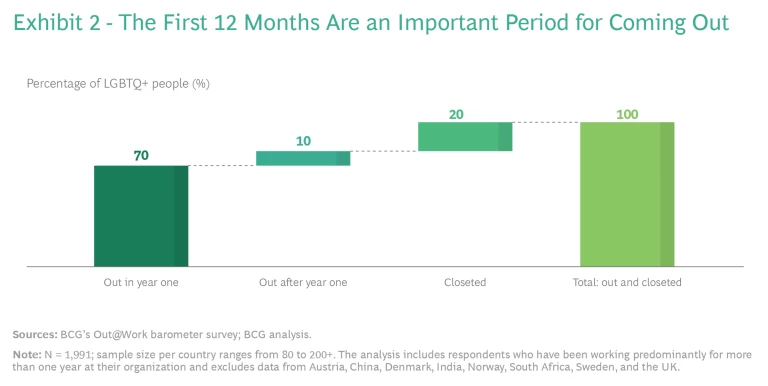

For most LGBTQ+ people, the first year in a new job is critical in the coming-out journey. Across the countries surveyed, an average of 70% of LGBTQ+ respondents said that they came out either during the hiring process or within the first twelve months of starting their job. (See Exhibit 2.) Just 10% came out after the first year, and the remaining 20% stayed closeted. We observed this broad trend across most of the countries we surveyed, except in India and China, where employees in general took longer to come out or chose to stay closeted: just 36% and 56% of LGBTQ+ respondents in India and China, respectively, said that they had come out by the end of their first year at work.

Approximately half of the respondents who had not yet come out stated that they did not plan to come out at all, with more than 63% of this group explaining that they considered their sexuality and gender identity to be a private matter.

Why LGBTQ+ Employees Sometimes Stay Hidden

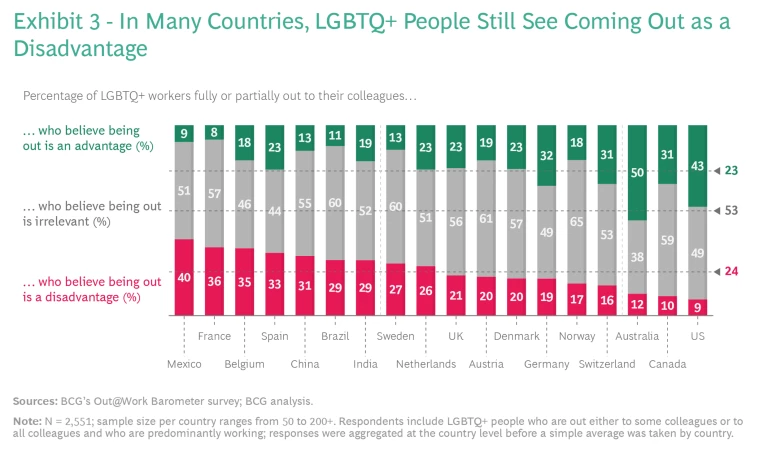

Coming out at work can involve significant challenges. On average across all 19 countries in our survey, 53% of LGBTQ+ people who are partially or fully out in their workplace believe that being out at work is a neutral factor professionally, and 24% see it as an advantage. On the other hand, 23% see coming out in the workplace as a disadvantage. Many LGBTQ+ people worry that coming out in the workplace is a potential risk to their careers, and respondents who are not out at work cited this concern as a top reason not to come out.

We also observed significant variations across countries. (See Exhibit 3.) For instance, 50% of LGBTQ+ respondents who are partially or fully out in their workplace in Australia see being out at work as an advantage; but in several developing countries, including Brazil, China, India, and Mexico, this figure drops to just 9% to 19%. And in Mexico, fully 40% of such LGBTQ+ respondents said that they see coming out at work as a disadvantage in their careers.

We also asked LGBTQ+ respondents whether they had experienced discrimination in the workplace, including such specific types as discriminatory jokes, not being taken seriously, and a lack of social inclusion (or outright exclusion). Overall, when averaged across all 19 countries in our survey, 58% of LGBTQ+ respondents said that they had experienced discrimination—and interestingly, except in Sweden, this rate was highest among those who described themselves as “partially out.” On average, members of this group of respondents were 9% more likely to say that they had experienced discrimination than those who deemed themselves “fully out.”

We found a number of significant differences with respect to discrimination (as well as to some other subjects that our survey addressed) among women and trans and gender nonconforming colleagues. (See “The Reality for Trans and Gender Nonconforming Employees” and “The Challenges for LBTQ+ Women.”)

The Reality for Trans and Gender Nonconforming Employees

Overall, these employees were approximately as likely to be out to family, friends, and colleagues as LGBQ employees were—and our data showed that they were more likely to be out among clients and customers. The daily choices involved in being out seem to be more challenging for trans and gender nonconforming respondents, however: these respondents report themselves as being 20% more likely to lie, omit details, or avoid answering questions about their sexuality than LGBQ respondents (44% for trans and gender nonconforming respondents).

Trans and gender nonconforming respondents were also more likely to see being out as a career disadvantage (32% of trans/gender nonconforming respondents versus a global average of 23% across LGBQ respondents).

Worrisomely, trans and gender nonconforming respondents reported higher levels of discrimination, too, with 74% of respondents reporting instances of discrimination (vs 57% for LGBQ respondents). This trend was even starker in Europe, with 72% of trans/gender nonconforming respondents reporting instances of discrimination (versus 53% for LGBQ respondents).

The Challenges for LBTQ+ Women

Our survey found that the share of LBTQ+ women who remain fully in the closet to colleagues is about 9 percentage points higher than the share of GBTQ+

In dealing with the recurring daily choices involved in covering or uncovering their identity, women were about 12% more likely than men overall to cover up when asked about their sexual orientation (35% for LBTQ+ women respondents compared to 23% for GBTQ+ men).

Why the difference? When we look at the type of discrimination experienced by both LGBTQ+ men and women who are out, women report a 13% higher incidence of sexual harassment than men. At the same time, women who described themselves as closeted reported, on average, 10% less discrimination than GBTQ+ men who were closeted, averaged across respondents in all countries. This may help explain why some women prefer to remain closeted.

The Power of Inclusion

By creating a culture of inclusivity that makes LGBTQ+ employees feel comfortable in sharing their identity, companies can reap significant benefits. Given the relatively large number of LGBTQ+ people who are out in the developed world, we took a closer look at the experience of those individuals in the workplace. LGBTQ+ respondents who described themselves as “fully out” were about as comfortable speaking up, being themselves, and building friendships at work as survey respondents from the majority “straight” group were. But fully or partially closeted respondents were less comfortable on all three

We know from other BCG research that inclusion is an important factor not only in how people feel at work but also in where people want to work. A recent study in Southeast Asia, for example, found that 90% of employees with underrepresented diverse identities said that they would leave a company if it lacked leadership commitment to inclusion and diversity, and the equivalent figure looking across all staff was 57%. That research estimated the cost of replacing those workers at more than $25 billion per year.

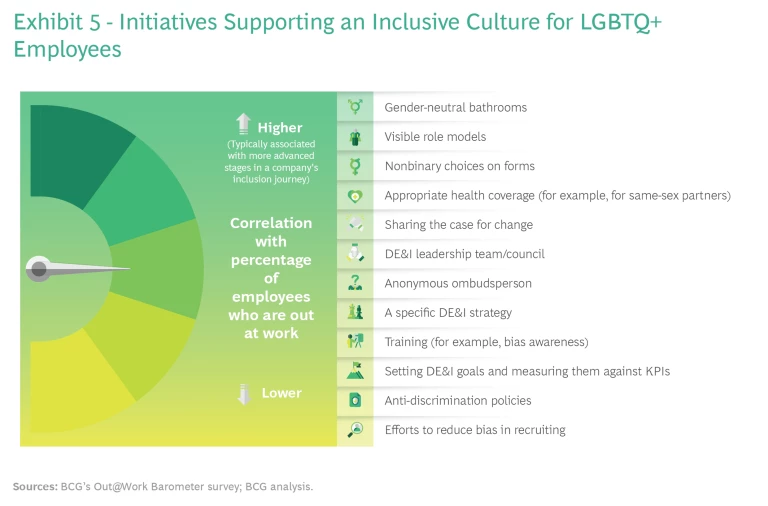

Encouragingly, our survey suggests that some companies’ efforts to build an inclusive culture are having a positive impact. Our assessment of the impact of 12 inclusion initiatives found that all of them correlated with higher rates of LGBTQ+ employees who were out at work. Among these, gender-neutral bathrooms, visible role models, and nonbinary choices on forms showed the highest correlation. (See Exhibit 5.) Not surprisingly, these measures often correlate with more advanced stages of a company’s inclusion journey. There was also an additive effect: respondents from companies with higher numbers of initiatives in place were more likely to be fully or partially out at work. This data suggests that companies need to employ a broad set of measures to foster a truly inclusive workplace.

Walking the Walk

Given that employees who are out at work say that they feel more empowered, more comfortable, and more socially connected, what can companies do to make LGBTQ+ employees feel included and supported from the start?

The answer is not simply to roll out myriad new initiatives. Instead, companies must develop a holistic plan to ensure that all stages of an employee’s journey during the first critical year reflect and are shaped by a diverse, equitable, and inclusive culture. Five areas of focus are especially important:

- Foundations. Companies should ensure that they have the right HR policies and supportive infrastructure in place and that they are communicating these elements effectively. For example, they should connect LGBTQ+ employees with employee resource groups that provide community, affiliation, and support.

- Recruiting. Companies need to take steps to build a truly diverse workforce. Efforts should include targeting outreach to LGBTQ+ candidates, providing candidates with support through the recruiting process, and offering new hires early connections to a network of existing LGBTQ+ employees when they come aboard. Companies should also clearly communicate their inclusive policies and resources to candidates and new hires. And they should have processes in place to ensure that candidates have the option of maintaining their confidential status by coming out only to a limited, well-defined pool of recruiters.

- Onboarding. As LGBTQ+ employees are hired, companies should immediately connect them with mentors who can help them navigate their careers and can be a resource for managing any concerns or issues. Of course, not all LGBTQ+ members will choose to publicly self-identify as such on day one. That’s why it’s important to adopt universal communication strategies to ensure that new hires are aware of the company’s LGBTQ+ resources and programs, including measures to maintain the confidentiality of members, if they choose. Of course, local laws must be respected in all instances. In addition, mandatory sensitivity training sessions on LGBTQ+ topics should be part of new employee orientation programs to send early and strong signals regarding support and behavioral expectations.

- Day-to-Day Work Environment. Companies need to create a respectful, inclusive culture. Visible initiatives such as creating gender-neutral bathrooms and nonbinary choices on company forms can support such a culture. But it is just as important to ensure that employee interactions with colleagues, direct managers, and leadership—what we call the “1,000 daily touch points”—foster inclusivity. One way to achieve this objective is by instituting a structured program for allies that offers, among other things, sensitization training on diversity, equity, and inclusion. BCG research has shown that negative touch points—comments or actions that highlight prejudice, demonstrate a lack of empathy, or make an individual or group feel isolated or unwelcome—remain all too common in the workplace.

- Continued Engagement. LGBTQ+ diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives and efforts should not be a one-time exercise during onboarding. Rather, they should be a regular component of the company’s calendar, including frequent expressions of support, events that celebrate and recognize the Pride movement, and support of broader LGBTQ+ rights and inclusion.

The benefits of building a culture that encourages employees to bring their authentic selves to work are clear. Companies should understand that the first year of employment is a critical time for LGBTQ+ employees, when they will decide whether doing so makes sense for them. Employers that understand this and take steps to ensure that their commitment to inclusivity is clear from day one will be in a far better position to leverage the talent and power of their workforce.

The authors would like to thank Clarissa Mariani, Kate Myhre, and Jean Lee for their help with the report.