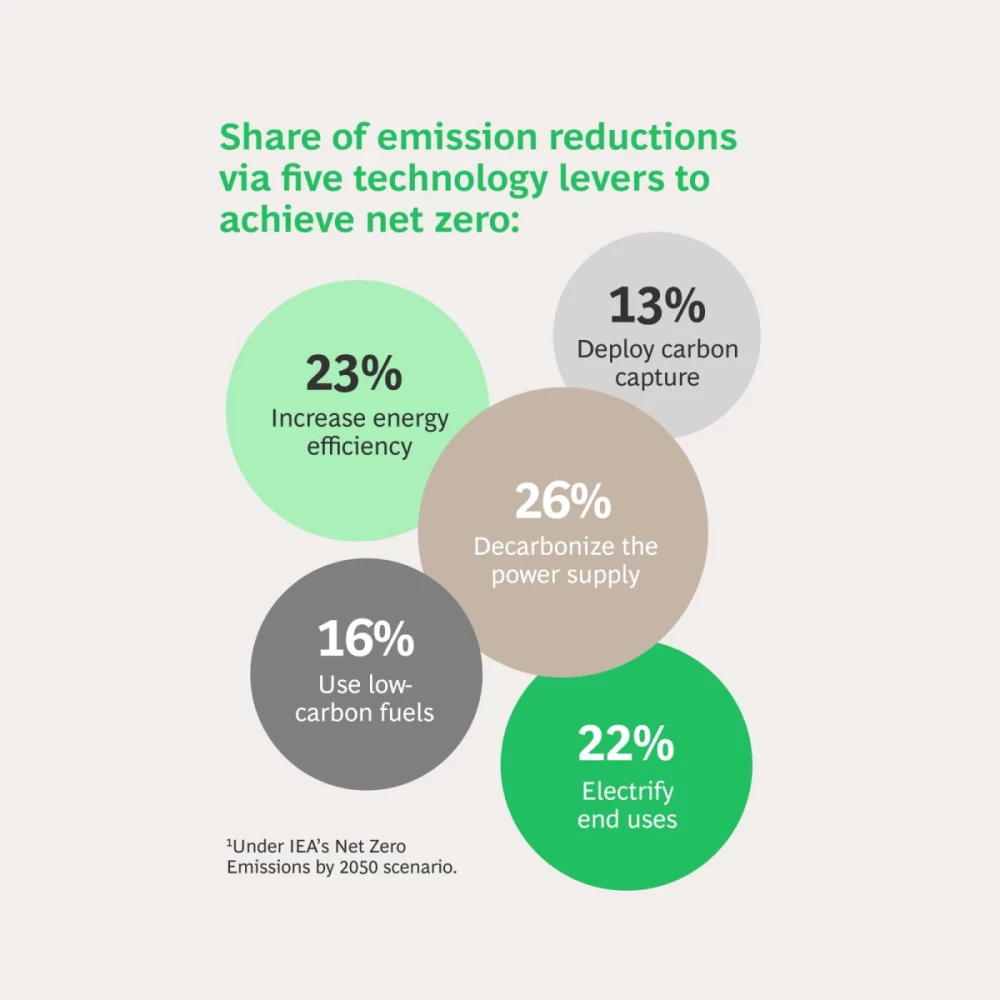

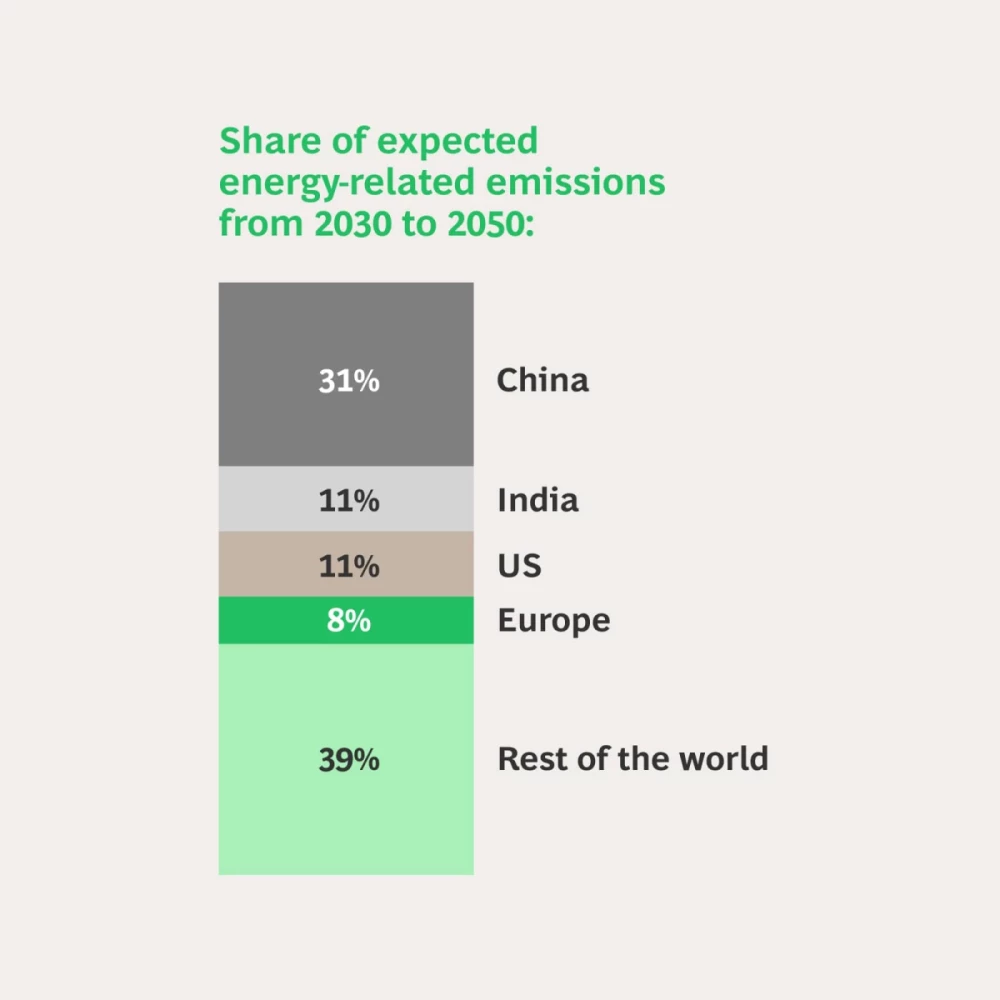

Society has gone through energy transitions in the past—but nothing like this one. The adoption of coal occurred over roughly five decades and the shift from coal to oil took more than three decades. To limit global warming to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, we must ramp up renewables and other low-carbon solutions at warp speed. These energy sources must match the maximum shares held by coal (55%) and oil (41%) roughly three times faster than those commodities did and ultimately account for most primary energy by 2050—up to 70% in IEA’s Net Zero Emissions scenario. This rapid transition remains a massive challenge and appears increasingly unlikely: current policies would permit warming to +2.7°C by 2100. And the speed of the energy transition in sectors such as industrial manufacturing and buildings is woefully insufficient.

So how do we accelerate progress to ensure that we can meet ambitious targets for 2030 and beyond? BCG has studied the energy transition in depth to build a blueprint that outlines ways to scale new low-carbon technologies, the global implications of the shift, and critical actions that policymakers, energy users, infrastructure providers, energy producers, and investors can take to move the needle. Over the coming months, we will publish a series of articles exploring many of these topics in greater detail.

A Tectonic Shift

Failure to bend the curve dramatically on emissions will have steep costs for the natural world and for the health and livelihoods of people around the globe. Evidence of these impacts becomes clearer every day—and at a concerning pace. We have the tools to get to net zero, but we do not have the policies, proven business cases, and capabilities in place everywhere to massively accelerate the pace of action. All stakeholders, private and public, need to do their part to effectively unlock concrete progress.

The Far-Reaching Implications

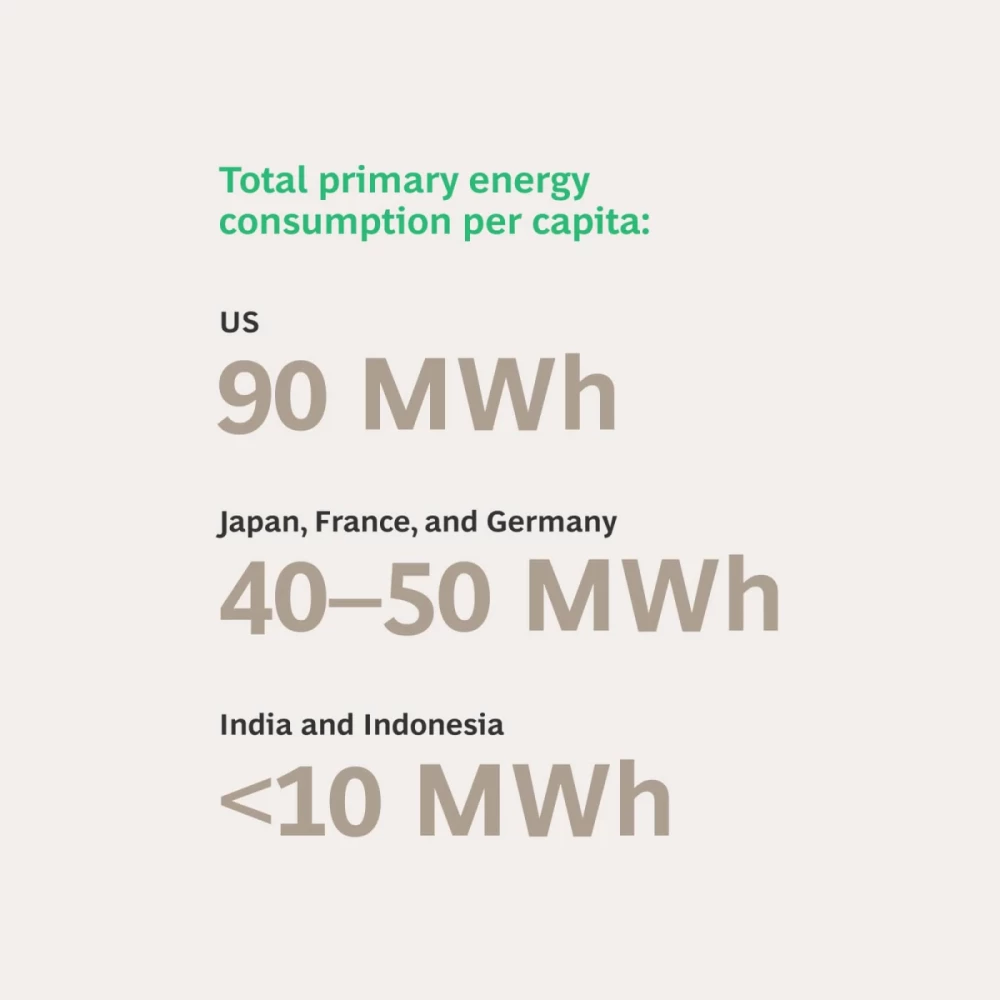

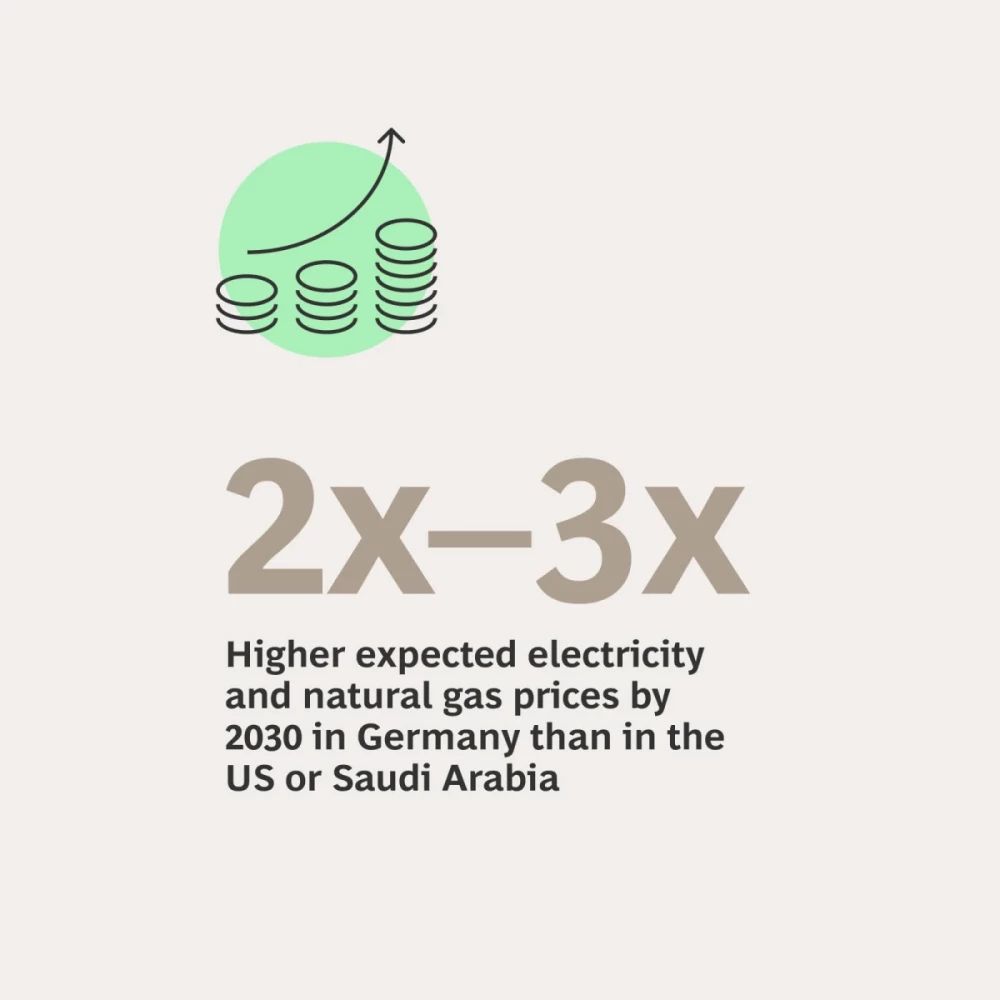

The energy transition is critical to preserving a livable planet. It will also drive major economic change—altering the economics of energy systems and markets and remaking the global competitive landscape. But if we successfully accelerate the transition, we can expand access to electricity and greater prosperity to the 775 million people who don’t have either today—and enable the even larger number of people who use very small amounts of electricity today to increase their usage.

Action Across the Energy Ecosystem

Policymakers

Close the Cost Gap

The energy transition will cost consumers in the short to medium term but pay off in the long term.

Many green products and technologies are still more expensive than gray alternatives when externalities are not priced in. (We currently price only 18% of global emissions from a carbon markets perspective.) Policymakers can level the playing field by taking steps to make non-green offerings more expensive (for example, through tax policy, carbon pricing, or removal of subsidies) or by making green products more cost competitive (for example, through incentives or public R&D funding). Recent developments are encouraging—particularly in the US, with its passage of the IRA, and in the EU, with its Green Deal Industrial Plan. The challenge now is to proceed to implementation, designing the appropriate regulations and disbursement mechanisms and alleviating bottlenecks.

Get Granular

Governments must set the stage for predictable, steady progress toward net zero.

Granular year-by-year deployment targets are critical to delivering on ambitious 2030 and 2050 goals. Stakeholders must coordinate these targets across industries and value chains. In some cases, government guarantees can advance efforts to achieve those targets.

Redesign Energy Markets

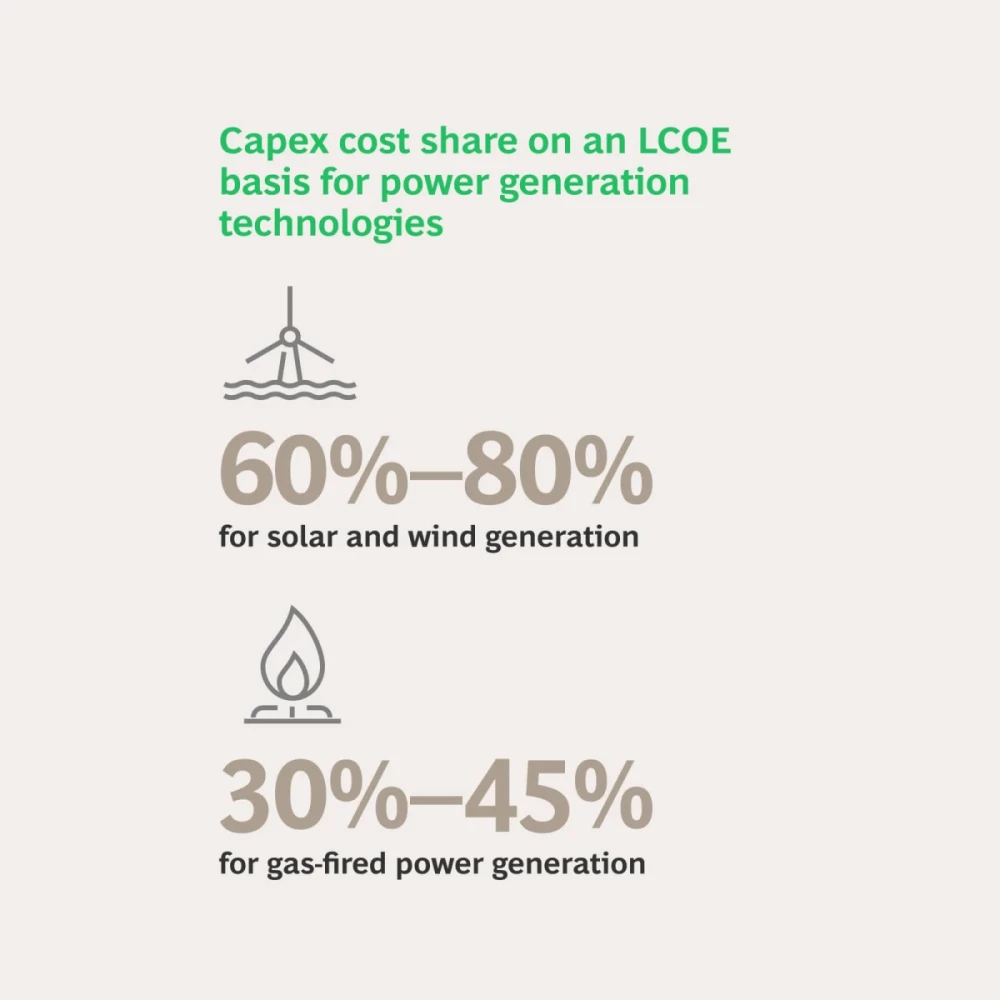

The energy system needs unprecedented levels of low-carbon investment.

Energy markets must evolve in three primary ways. First, planners must design energy systems and networks holistically and not shy away from configuring supply and demand in more optimal locations, when possible. Second, they must redesign electricity markets to provide the price signals needed to efficiently balance supply and short-term demand, and to incentivize an unprecedented level of investment. To this end, policymakers can enhance today’s market signals—for example, through carbon pricing and guaranteed revenue streams or subsidies. Third, energy markets must encourage energy consumers to modulate the timing of demand, including by shifting consumption toward off-peak hours.

Dramatically Cut Planning and Permitting Times

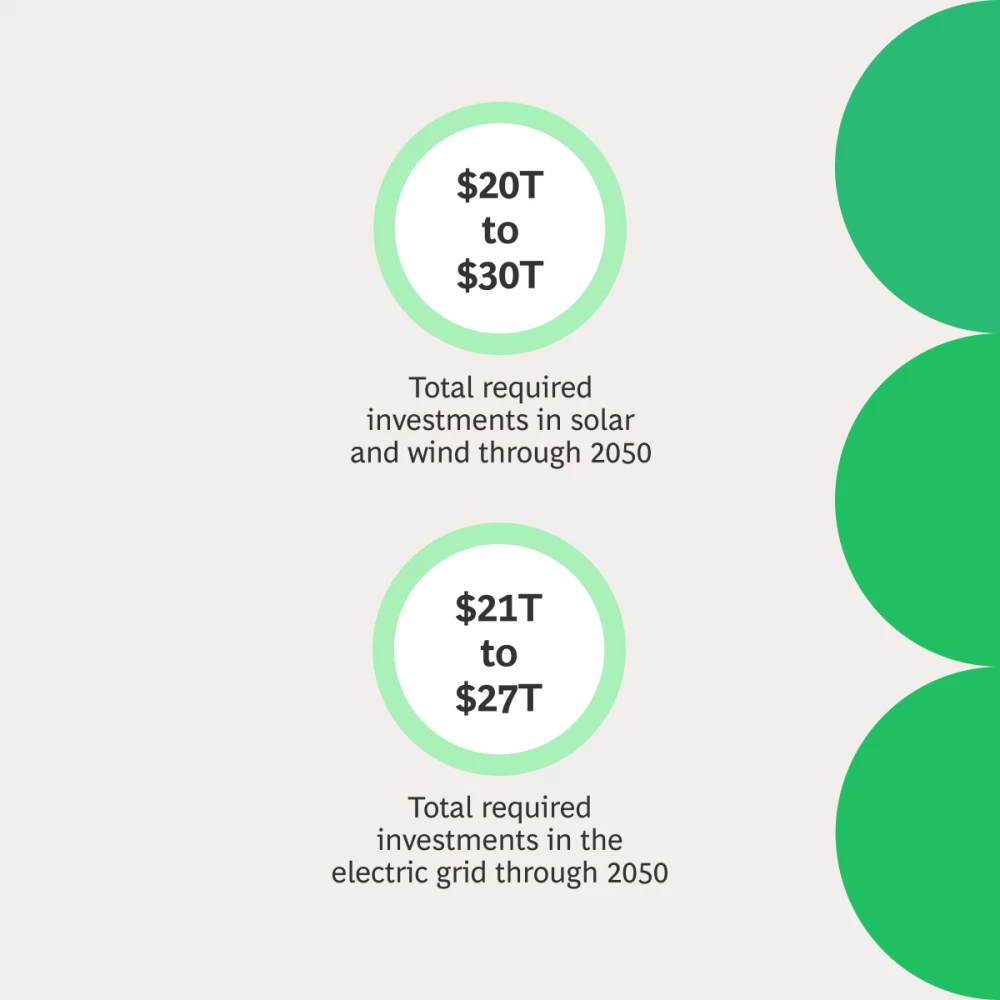

Large investment is needed, most notably to increase low-carbon energy supply and grid expansion.

In theory we have access to plenty of low-carbon energy. But time-consuming planning and permitting processes can severely impede rapid progress. Policymakers can streamline these processes to power rapid progress, particularly in expanding electric grids. Of course, instituting such procedural innovations entails overcoming major barriers, including potential pushback from public opinion.

Rethink Liability Frameworks

New low-carbon technologies are critical, but funding them carries some risk for investors.

Newer technologies—such as hydrogen and carbon capture, utilization, and storage—raise questions of liability uncertainty. For example, it may be unclear who should pay in the event of CO2 leakage. Potential financial risks of this sort, which can be massive, are slowing or even halting investment decisions. Updating and implementing redesigned liability frameworks can unleash significant investment.

Ensure a Just Energy Transition

The costs and benefits of the transition must be equitably shared.

During the energy transition, some traditional jobs will disappear and many new ones will emerge. Governments must ensure an equitable distribution of the positive and negative impacts of these changes across geographies and society. Ultimately, such equity will be critical to gaining and maintaining popular support for the transition. Advanced economies should also offer technical and financial assistance to emerging economies in support of their efforts to plan and deliver just transitions.

Large Energy Consumers and Energy Infrastructure Providers

Lock in Green Energy Supply and Infrastructure

Demand for low-carbon energy may outstrip supply.

Large energy consumers should ensure that they have reliable access to low-carbon energy (for which there will be real competition) and to required infrastructure such as hydrogen and CO2 networks and long-distance electricity transmission. Timing matters because there is risk that end-use conversion and transmission and distribution infrastructure will lag creation of new low-carbon demand.

Design Capital Expenditure Plans with a Long-Term View

Investments in heavy assets should take into account the pace of scale-up in demand.

To avoid falling behind, heavy industry players must make capital expenditure decisions that are economic over the long term, even if the investments do not yield high returns in the short term. At the same time, they must bear in mind the risk of stranded assets created by an accelerated transition.

Build and Support Low-Carbon Ecosystems

Given the scale of investment needed, companies cannot go it alone.

Business cases for many large investments in low-carbon production, infrastructure, and offtake assets have significant interdependencies, both between stakeholders and in the timing of investments. Consider hydrogen. In order for hydrogen markets to develop, end users must convert to its use, transport must be built out, low-carbon power must become widely available, and electrolyzers must be built on a large scale—all in the right order over time. Clearly, collaboration (including public-private partnerships) across sectors and along the entire the supply chain is critical in this process.

Energy Producers and Suppliers

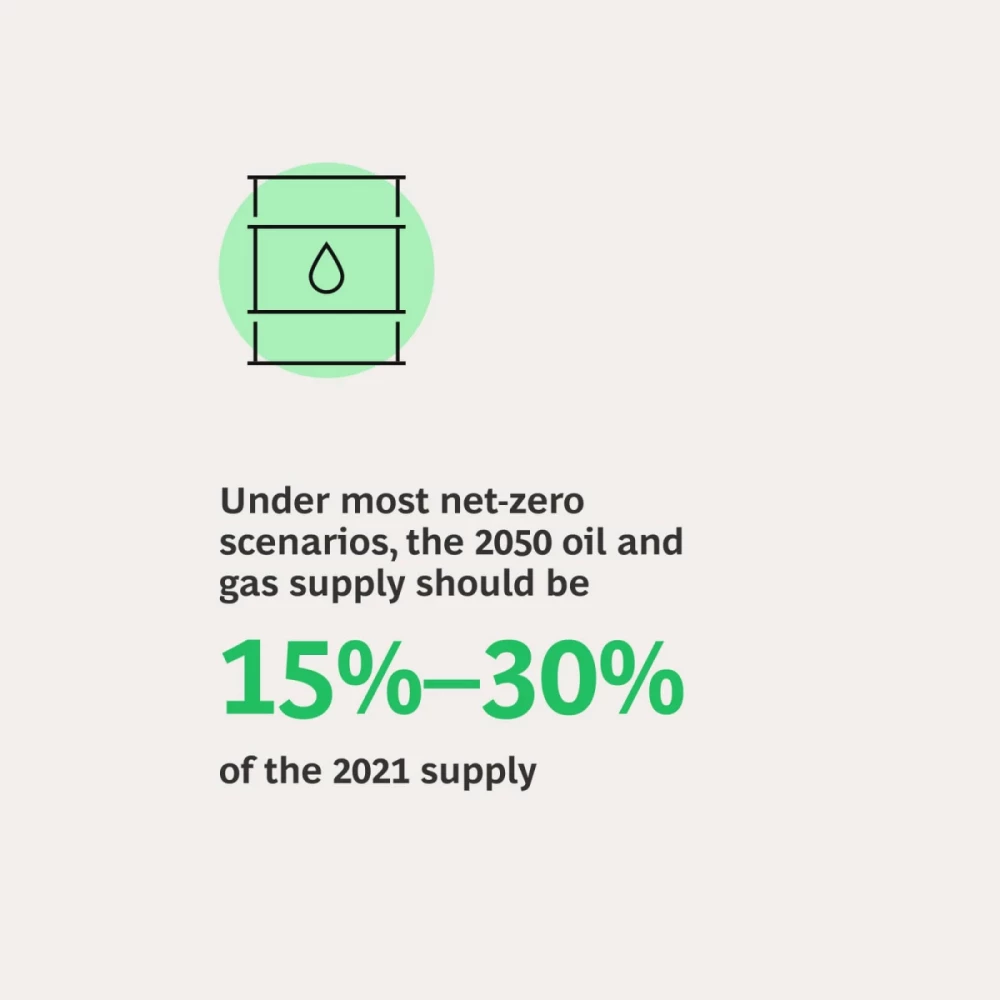

Ensure a Responsible and Resilient Supply of Oil and Gas

As demand for fossil fuels declines, the risk of price shocks and volatility will increase.

To minimize those risks and avoid the added costs of stop-start investment cycles, energy producers and suppliers must arrange for a reliable supply of oil and gas. At the same time, they have an obligation to reduce fossil-fuel-related GHG emissions—in the short term through methane leak elimination, and in the short and medium terms through Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions reductions and carbon capture, utilization, and storage. In parallel, they must invest aggressively in direct-air capture R&D and in pilots at scale to ensure the technology’s viability.

Lead on Low-Carbon Energy Production

Building out a new energy system requires massive capital and expertise.

Producers and suppliers can leverage strong balance sheets and their technical and operational know-how to help orchestrate complex energy systems and ecosystems. Individually, players need to clarify their strategy—for example, whether they will operate as a pure play or as an integrated energy provider.

Develop Tailored Energy Supply Portfolios

Different markets will need different mixes of low-carbon energy sources.

In some regions, green fuels may be a good fit; in others, using renewable energy to meet higher levels of electrification may be more suitable. Producers and suppliers can develop business cases and roadmaps that reflect those differences, and they can work with policymakers to shape regulations that support the right mix.

Design the Right Solutions

Customers will need flexible, integrated hydrocarbon and low-carbon energy solutions.

As customers transition from fossil fuels to low-carbon energy in their operations, energy producers must help them find pathways to transition effectively over time and avoid disruptions. For example, energy producers can offer industrial manufacturers heat as a service, independent of whether the source of the heat is fossil fuels or renewable energy. This will enable the manufacturers to reduce their carbon footprint while also limiting their need to invest in new assets or processes.

Plan for Volatility

Customers should not bear the entire burden of increased price volatility customers.

Not all customers, particularly residential or small commercial, are well equipped to absorb large increases in price volatility. As in many other industries, large swings in producers’ supply costs need not be passed on to customers. Energy suppliers should understand customer preferences regarding volatility and design innovative products that match those preferences.

OEMs and Low-Carbon Technology Companies

De-risk and Diversify Supply Chains

The energy transition hinges on global value chains, so ensuring resilient supply is key.

Both OEMs—including all producers of equipment along the low-carbon supply chain—and low-carbon technology companies should ensure that their supply chains are robust and do not rely too heavily on suppliers in any one country. This means diversification, not decoupling.

Monetize the Power of Scale

The benefits of producing on a large scale can accelerate the transition.

OEMs should push for scale in low-carbon technologies to bring down costs and, ultimately, prices. In doing so, they should take advantage of supportive policies—for example, the Production Tax Credit in the IRA in the US.

Balance Innovation and Standardization

There is a clear path to scale in emerging low-carbon value chains.

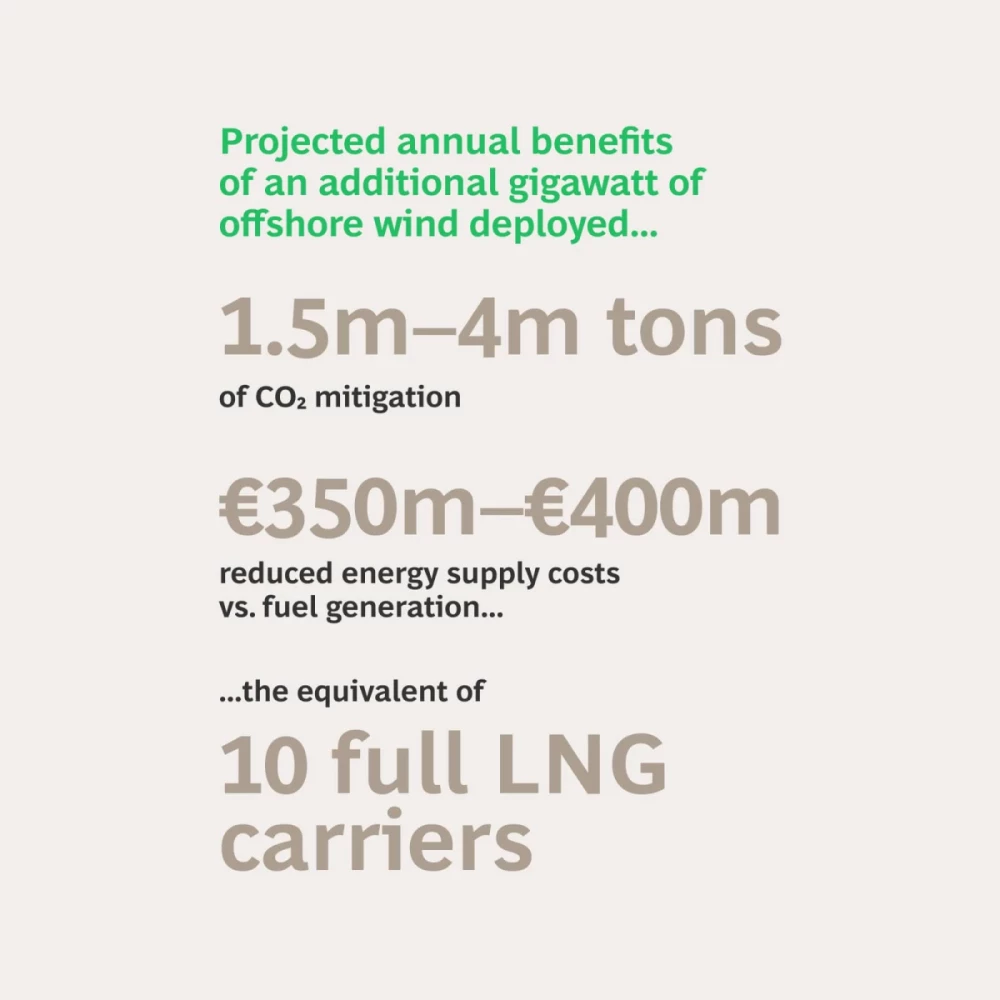

Technological advances can help OEMs and low-carbon tech companies lower costs and improve efficiency. For example, the power generation capacity of the average operational wind turbine has quadrupled over the past two decades. As technologies mature, however, players should establish standards to drive industrialization. The right standardization can provide opportunities to lower costs in the medium term—not only for the component manufacturing industry, but also for the downstream value chain. Conversely, a lack of standardization might require endless, costly modifications, such as (in the case of wind power OEMs) continuous upsizing and alteration of vessels and other logistics for installing offshore wind.

Investors and Financial Institutions

Engage with Regulators and Governments

We need to unlock unprecedented levels of investment.

Investors and financial institutions can work with the public sector to install long-term investment signals, including standards for measuring emissions and verifying that companies have taken certain decarbonization actions. Doing so will promote a more level playing field and a more accurate valuation of the externalities that exist today, ultimately increasing the pace and overall coordination of capital spending.

Do Not Lose Sight of Infrastructure Investments

The success of the energy transition will depend on new networks and infrastructure.

Investors and financial institutions must identify sound investments in networks and other shared infrastructure to ensure that sufficient low-carbon production is built. From now until 2050, the global electricity grid alone will require investments totaling more than $21 trillion. Larger connected zones, including for electric grids or hydrogen networks, will eventually yield lower commodity costs.

Consistently Integrate Carbon into Decision Making and Asset Valuations

New approaches are necessary to close the energy transition investment gap.

Investors must systematically embed consideration of carbon in their decision making process. This assessment should encompass regulated carbon costs, internal carbon costs, indirect carbon costs (related to Scope 3 emissions), and value created through the company’s decarbonization efforts (such as demand for the resulting low-carbon alternatives).

Apply a Programmatic Approach in Financing

Funding green projects piecemeal is slow and limits the agility of funded companies.

Investors and financial institutions need to move beyond financing individual projects and instead directly finance companies that are deploying low-carbon technologies. This will enable those companies to move capital between projects as situations for each evolve.