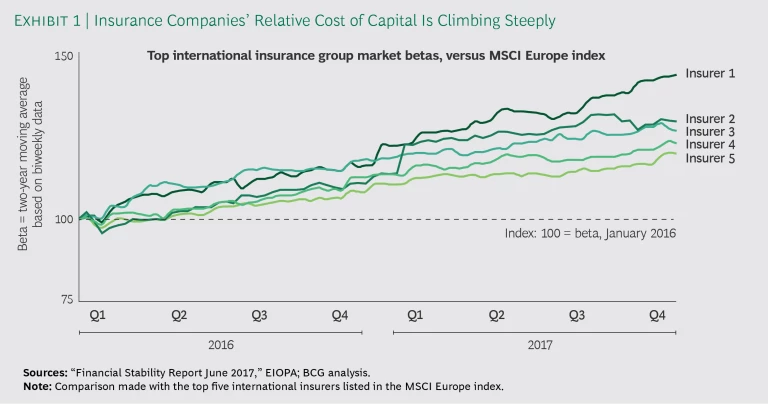

In the past few years, the cost of capital for insurers has climbed far faster than it has for other industries. (See Exhibit 1.) As a consequence, capital has to be managed more efficiently in order to deliver higher returns.

At the same time, profitability is in retreat. In the EU, the average return on equity for insurers has fallen from around 11% in 2014 to about 9% in recent years. Insurance executives know all about the main drivers of this reduced profitability—including the challenges posed by rock-bottom interest rates in life-insurance products, disruptive startup competition, and the new waves of regulation that add cost and complexity.

It’s a good bet that economic and market conditions will keep the pressure on insurers’ margins and overall profitability. There’s little likelihood that the cost of capital will decline—given the surge in volatility that will come with the wave of new regulations, such as IFRS 17. Financial markets are on alert, and analysts increasingly demand to know what insurers are doing to improve use and management of capital.

Insurers have no choice but to manage their increasingly expensive capital much more effectively. As such, the measurement of return on capital becomes a crucial part of governance, driving decisions to move capital away from underperforming to high-achieving products or business sectors—and, when possible, giving back to shareholders and lenders.

In responding to such demands, the industry is not starting from scratch. Instead, insurance leaders in Europe and the US have made capital management a fundamental part of their presentation to investors. Most provide regular updates on progress achieved year-on-year, emphasizing the implementation of risk-adjusted measures and new ways of managing, for example, life in-force portfolios—the stock of policies that will be extinguished over the next years. Some leading insurers choose to optimize portfolio initiatives, such as exiting riskier businesses, investing in capital-light opportunities, thinning out product portfolios, and reviewing new business, especially in life insurance.

A New Approach to Optimize Capital Management

All of that is a good start, but much more can be done. Although there’s no doubt about what the market is asking for, it’s easy for capital management to slide down the C-suite’s agenda as other priorities crowd in. What’s needed is a bold, determined move away from a mostly technical approach—one driven largely by accounting and regulatory considerations—to a mixed approach, in which the technical themes are complemented by weighing market opportunities, strategic bets, geographical footprint, and product and channel review.

BCG contends that most insurers have yet to unlock the full potential of capital management. We believe they can rethink their approaches, working assertively to identify and include strategic considerations and blend them with the traditional accounting-centered path. For example, they have to factor in strategic planning in order to complete the shift from a pure profit-and-loss focus to a perspective that integrates P&L and the balance sheet. They must review the geographical footprint of the whole group as well as the product mix. And they need to drill more deeply into the capital effectiveness of each business unit, with no unit considered sacred.

None of this is easy. Large groups typically have to deal with multiple solvency regimes. Similarly, they are up against a range of accounting processes. IFRS, for example, is generally reported publicly, whereas GAAP is examined by local regulators and authorities and can impose constraints that are hardly visible to the head office. As a result, there can be enormous variations across business lines and geographies, making it difficult to produce apples-to-apples comparisons of performance. Moreover, insurers confront huge differences between profitability and cash generation, which makes it much harder to easily reallocate capital.

With such real-world complexity in mind, BCG has developed an approach that leverages all of the capital-management efforts made by today’s leading insurers and takes them to the next level. This optimization approach involves three steps:

- Redefining capital for insurers, and identifying how to measure its productivity

- Pinpointing every business unit’s role in creating value for the group, from both a financial perspective (capital productivity) and a strategic perspective (market attractiveness and competitive positioning, for instance)

- Reallocating resources across the group to improve value generation

Each step merits a closer look:

1. Redefining Capital for Insurers, Measuring Productivity. Measuring return on capital is a crucial aspect of capital governance. It can drive key strategic decisions—such as whether to discontinue businesses—and it allows for the review of geographical presence as well as product and channel mix.

An appropriate measure of return on capital requires answering two key questions: what is capital and what are the returns? While the latter is usually straightforward—the amount of profit generated by the analyzed business unit, product, and so on—the former requires addressing a set of methodological points.

From the regulatory perspective, risk capital (also known as Solvency Capital Requirement) indicates the amount of capital that a regulator will ask an insurer to hold in order to cover the risks to which investors are exposed.

From an accounting perspective, IFRS capital employed—that is, equity and financial debt—refers to the resources invested in the group by external investors. This measure gives a view of the returns sought by investors.

And from a solvency perspective, “own funds” indicate the total amount of resources that can be used to determine an insurer’s solvency, including not only invested resources but also future profits, excess reserves, policyholders’ funds, and more. This is the capital available to cover regulatory requirements.

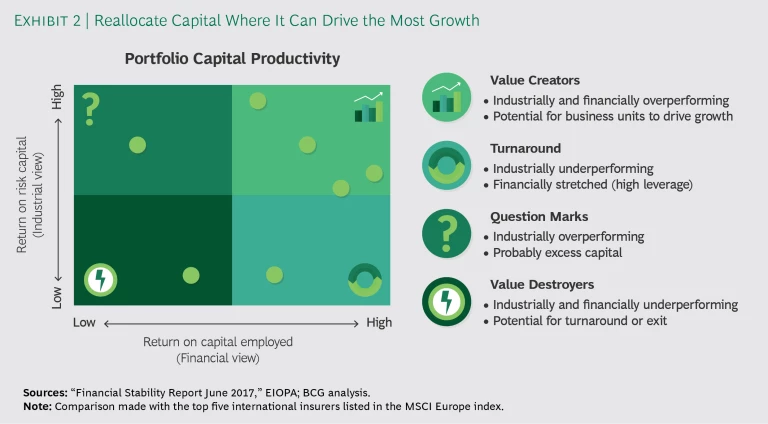

To determine how to measure the productivity of capital, BCG’s approach involves two perspectives: industrial, assessing return on risk capital (RoRC) to measure profitability against the volatility of expected results; and financial, using return on capital employed (RoCE) to track profitability against actual invested capital. The two perspectives are complementary and equally important for disaggregating and assessing business unit performance. (See step 2.)

The relative importance of those perspectives depends significantly on the circumstances. In some jurisdictions—Germany, for example—and in some lines of businesses, such as life insurance, insurers are permitted to cover their risks with sources other than actual capital employed and can significantly leverage their balance sheets. Those firms can grow their businesses by investing little or no additional capital; as a consequence, they can drive up RoCE but not necessarily their RoRC.

In other circumstances—in typical property and casualty businesses, for example—the opposite happens: growth can be financed mostly by investing more capital, which means that RoCE and RoRC tend to move in the same direction. In those cases, it’s critical to consider both perspectives equally—even if some business units indicate a preference for being valued with one or the other perspective.

Finally, after the identification of relevant capital-productivity metrics, it is critical to define appropriate hurdle rates both for RoCE and RoRC across different business units. Indeed, different business and risk profiles, as well as capital structures across groups, may justify differentiation in return on capital hurdle rates. The riskier, more leveraged, and more volatile a business unit is, the higher its implied cost of capital. The appropriate definition of business-specific hurdle rates, while methodologically complex, is a crucial step for a more objective measurement of each business unit’s contribution to overall group capital productivity.

BCG’s approach takes into account all these complexities and is able to identify the appropriate measure of return on capital to support key strategic decisions by top management.

2. Pinpointing Business Unit Contributions to Overall Capital Productivity. Once capital-productivity metrics have been decided and hurdle rates set, the firm needs to identify areas that create, as well as destroy, value. BCG’s optimization approach achieves this by disaggregating portfolio performance across the group along the industrial and financial dimensions described above. (See Exhibit 2.)

By mapping all of their business units in this way, insurers can quickly pinpoint the top and bottom performers in terms of RoRC and RoCE versus their respective hurdle rates, as well as the turnaround business-unit candidates and those with excess capital that are “question marks.”

But the pinpointing analysis is not complete until the strategic perspective has been considered, too. A firm may well accept losses or low capital productivity in the short term if its business leaders believe there is potential for growth in the longer term. So it is crucial to gauge each business unit’s outlook in terms of market attractiveness—that is, how much a given market can contribute long term to the profitable growth of the overall business. It’s also important to consider the competitive positioning of the group in each of its markets, since growth investments are more likely to produce strong returns when supported by scale or aimed at achieving a competitive advantage in the overall market or in some specific niche.

The pinpointing analysis can then spur actions in several areas. Strategically, it can enable insurers to change their business and portfolio mix; we have seen groups whose analyses helped them decide to exit certain businesses when it did not make sense—strategically and financially—to stay, or to switch to other more attractive businesses. Operationally, it pushes insurers to embed risk and capital returns considerations into day-to-day activities and decisions. In some cases, groups translate their analyses into risk loadings applied to the pricing of new products—in order to ensure adequate risk and capital remuneration of their offering.

The analysis can also help improve specific business performance. Several large insurers have strengthened their life in-force management programs, product portfolio reviews, or their technical excellence programs in P&C as a result of their pinpointing work. The analysis can also help firms decide to trim their portfolios or push for single business capital intensity. Some have launched big de-risking programs, either in terms of adding more capital-light products or disposing of capital-intensive pieces of the portfolio—or both.

3. Reallocating Capital to Improve Its Productivity. This step builds on the previous two. It identifies where there is excess capital and which business units or regions could benefit from greater investment, determining how to move the cash so that it can be more productive and taking into account any regulatory constraints. This step also moves the firm closer to decisions about major changes in its footprint: turnarounds or exits from business segments or regions that are not adding enough value (or are actually destroying value) or acquisitions of operations that have strong growth potential.

As noted earlier, this step can be extremely challenging, for all sorts of regulatory reasons and because of the complexities of various accounting rules and solvency regimes. However, most insurers have achieved significant results by emphasizing good governance of capital internally. Leading insurers often link capital management to a business unit performance-management system, setting incentives based on RoCE. This approach can be successful in putting pressure on local management to push excess and mostly unused capital resources to the head office and focus on short-term profitability as well as longer-term capital generation—allowing for more systematic flows of profit and capital upstream from local entities.

Making resources available centrally can then make it easier to redeploy capital—financing growth in sectors and products that offer more opportunity, for example, or returning equity or debt capital to investors if attractive internal options can’t be found. These capital-management-driven levers, when applied in the industry, have proved to be a solid source of value creation for insurance groups and their shareholders.

Let the Journey Begin

For any large insurer, the shift to truly effective capital management is a multiyear journey. (It has taken the industry’s best managers of capital close to a decade to reach their levels of efficacy.)

But long before the journey is over, shareholders can start to see real benefits. In BCG’s experience, insurers that develop strategically geared capital-management frameworks steadily step up their industrial performance. They build the processes and capabilities that allow them to move cash among their business units—dynamically and accountably—so it can be put to work more productively. And they have what’s needed to change the footprints of their organizations to support revenue growth and strong profitability far into the future.

The journey toward optimal capital management is as complex as it is long. It requires resiliency and persistence, demanding the wholehearted and consistent engagement of the top management team and, above all, of the CEO. There are four imperatives that insurers need to keep in mind in order to create value for their shareholders:

- Improve industrial performance.

- Identify, propose, and, if necessary, pursue discontinuity actions (potential M&A on one end and possible selloffs on the other).

- Lay the groundwork for moving resources from one operation to another.

- Ensure that all the potential actions align with the pertinent regulations.

Even though a capital management overhaul doesn’t happen overnight, the process should not be allowed to proceed at a leisurely pace either. Time is not on the side of insurers. The business model typical of today’s firm may be starkly different ten years from now. Between now and then, firms will have to scale to compete in fast-changing markets—or seek out specific niches. Most players are proactively seeking an M&A strategy.

The good news is that in a short time frame an insurer can set out its broader ambitions for using capital much more effectively and have a detailed plan to communicate throughout management layers—sharing it soon after with the investment community and other stakeholders.

BCG’s longtime experience and track record with highly complex, companywide value-creation initiatives give insurers the confidence to succeed. Our close working relationships with CEOs means we can help them see the difference between simply blessing an initiative and actively leading it—a recognition that sets expectations for the rest of the top management team.