Over the past few years gender diversity—and particularly increasing the representation of women in leadership roles—has become an important topic for companies. Gender diversity in leadership has been shown to improve workplace Diversity at Work , innovation , financial returns, and employee engagement . The economic opportunity of boosting female participation and bridging the wage gap has been projected to be well over $100 billion by multiple sources. (See Prosperity@150 for more on how this can help bridge our future workforce gap.)

The question is no longer “if” or “why” gender diversity is important, but rather “how to get there.” Although companies invest time, money, and energy on a variety of diversity initiatives, progress remains slow and there is limited understanding of what actually works.

The Boston Consulting Group recently completed a global study to examine that topic. The results provide a clear playbook to company leaders on how to improve gender diversity. By clarifying misperceptions and applying a structured approach, companies can ensure that they are making the most effective use of their time, investments, and management focus—and generate lasting results. Based on the results of the study, there are four priorities for companies:

- Conduct the analysis needed to clearly define the problem

- Build a portfolio of tailored interventions

- Take a programmatic approach and track progress

- Lead from the top

Canadian Insights

We surveyed 17,500 employees and interviewed representatives from more than 200 companies across various industries in 21 countries around the world, including Canada. We examined the impact of 39 gender diversity interventions, with a goal of understanding what’s actually working, as detailed in the global report Getting the Most from Your Diversity Dollars . In Canada, we spoke with representatives from 28 companies across major industries and surveyed more than 1,200 employees.

The key insights from that analysis include the following.

The glass ceiling remains intact

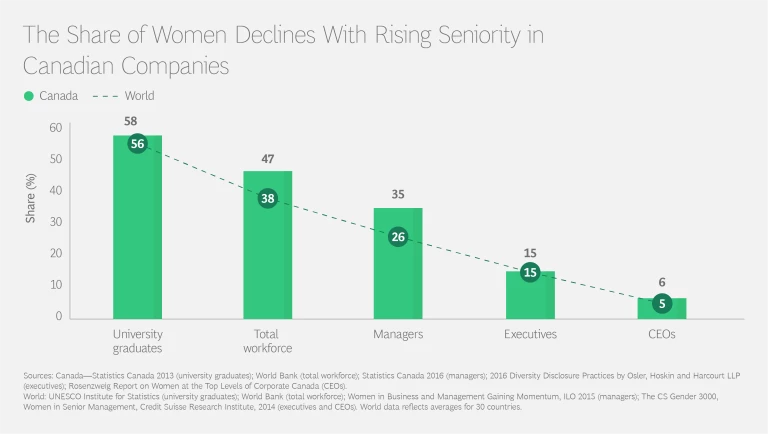

Canada ranks among the global leaders when it comes to female education levels and labor participation rates. However, at more senior levels, the percentage of women falls to the global average. Women in Canada have relatively healthy access to employment opportunities early in their careers, but they are simply not scaling the corporate ladder at the same pace as men.

There is a significant gap in perception between Canadian men and women on the issues of gender diversity

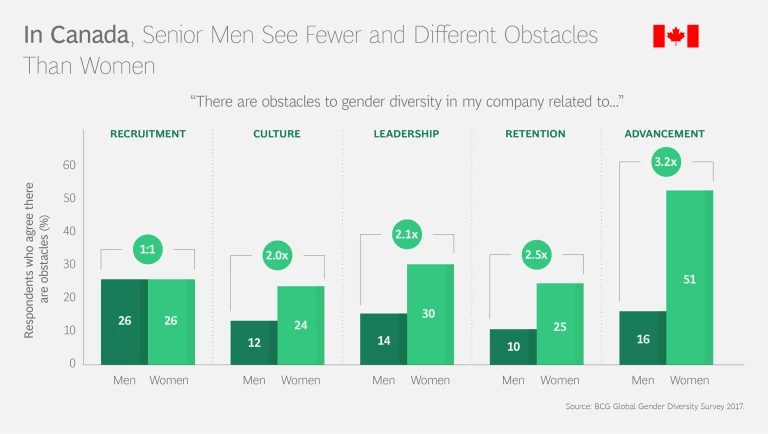

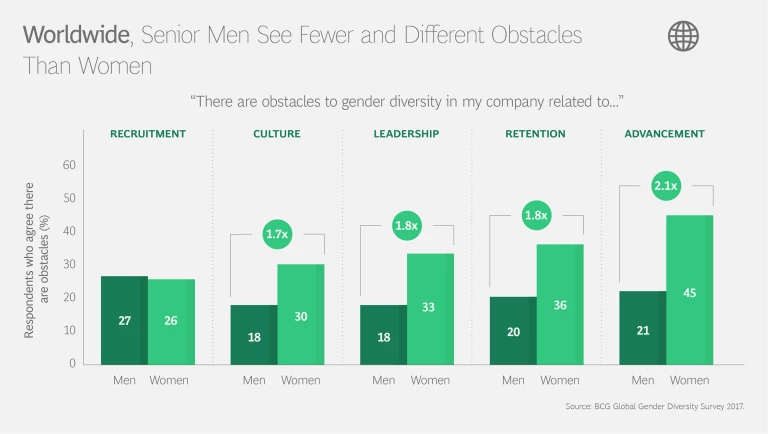

The global study shows that there is a gap worldwide between how male senior leaders view the obstacles to gender diversity and how women view those obstacles. Senior male leaders see recruiting female employees as the major obstacle, while women consistently point to advancement, retention, and leadership as more important. This perception gap is significantly higher in Canada than the global average.

Regarding advancement, for example, women in Canada are more than three times more likely to identify advancement as an obstacle than men, compared to 2.1 times more likely worldwide. This wider perception gap in Canada is also true for retention, culture, and leadership.

The takeaway: Many senior male leaders in Canadian organizations appear significantly out of touch with the obstacles their female colleagues and employees face.

Many Canadian companies are still nascent in their approach to gender diversity

Across the 28 large Canadian corporations we surveyed, BCG found three archetypes of companies based on their maturity level in addressing gender diversity: nascent, committed, and persistent.

More than a third of the companies covered in the survey are classified as “nascent.” These companies are experimenting with their diversity agenda. Although they recognize gender diversity as a business priority, they are in the early days of implementation and many initiatives are ad hoc. Leaders at these companies have done limited analysis to understand the issues or set concrete objectives.

Approximately a third of companies in the survey are classified as “committed.” These companies have started to put a more programmatic approach in place. They are more analytical in understanding the issues women face within the company and more diligent about launching focused initiatives with clear KPIs. Most committed companies have assigned ownership for the diversity agenda to a designated leader or group, and they are working to enlist and engage the broader management team to implement the agenda as a business priority.

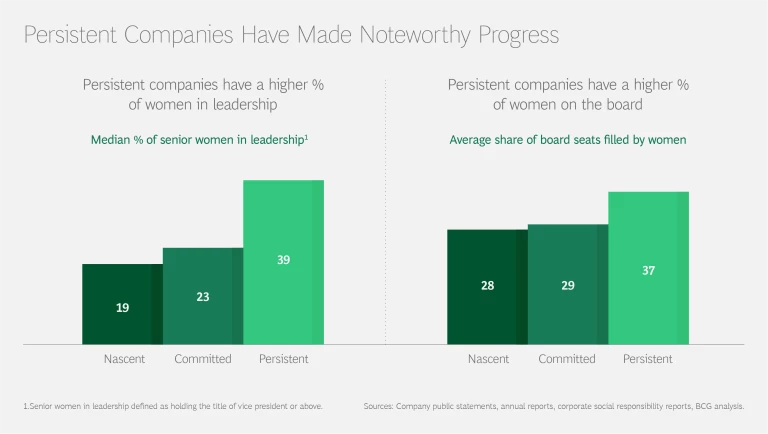

About a quarter of the companies covered in the survey are classified as “persistent.” These companies have been actively implementing a focused diversity agenda for several years. They take an end-to-end approach to program implementation and have made progress: the persistent companies in our sample have, on average, 39% of women in senior leadership positions, compared to 23% for committed companies and 19% for nascent companies.

However, representatives from many of the persistent companies admitted concern that progress has plateaued. In these companies, the focus now turns to the most challenging interventions, including attempting to systematically eliminate bias from all people processes.

Four Priorities to Move the Needle

The results also point to four clear priorities for companies seeking to make progress in gender diversity.

1. Conduct the analysis needed to clearly define the problem

When a company’s senior leaders (who are typically men) identify different obstacles than women, companies waste time, money, and management focus trying to solve the wrong problem. Instead, Canadian companies need to conduct the analysis needed to identify the real obstacles in their organizations. This includes looking at data across the entire value chain for talent—through recruitment, retention, and advancement—to understand where the drop-off points are for women.

The analysis should look at the unique factors within individual business units, functions, and geographies. For example, obstacles in the Atlantic retail branch organization of a bank will be different from those in the capital markets division in Toronto. Companies should also seek qualitative input from employee surveys, focus groups, and exit interviews. This fact-based analysis is needed to clear up misperceptions at the leadership table and focus the conversation and solution on the true underlying problem.

2. Build a portfolio of tailored interventions

Leaders at many nascent companies believe that there should be a silver bullet that solves the issue. They are often disappointed when individual measures don’t lead to progress and sometimes even reduce the ratio of women in the leadership ranks. Progress requires a portfolio of interventions, targeted at each of the obstacles uncovered in the analysis stage described above.

Furthermore, in the global study on this topic, BCG found that not all interventions are created equal. There are significant differences between the initiatives that male senior leaders perceive to be effective and those that female employees perceive as effective. When creating a portfolio of initiatives, companies need to include proven measures that are valued by both female employees and male leaders. These include challenging measures such as flexible working models, more visible role models for women, and public commitment and management support.

3. Take a programmatic approach and track progress

All of the persistent companies in the sample have taken a programmatic approach to diversity and have made notable progress. Taking a programmatic approach means doing the following:

- Conveying the business value of gender diversity consistently and with conviction

- Setting clear objectives, tracking KPIs

- Designing a tailored portfolio of initiatives, targeted at company-specific obstacles

- Rigorously implementing and monitoring initiatives

- Building momentum through quick wins, while working on harder long-term changes

However, change will not come from quick fixes. It takes time to address the pain points in the talent pipeline, combat bias in people management processes, and improve company cultures to be more inclusive and inspiring for women. Persistent companies in Canada have shown that results come from years of approaching the issues programmatically, tracking progress, and staying focused on objectives.

4. Lead from the top

As with any important program, leadership matters most. In persistent companies, gender diversity is a top priority for the CEO and is championed by leaders throughout the organization. These champions consistently communicate and reinforce the business value of a diverse workforce and support the initiatives by getting directly involved. Building a diverse and inclusive workforce is the accountability of all leaders, not just the HR department. Leaders are responsible for ensuring that interventions are properly implemented and accountable for making progress against objectives within their groups.

While female leaders surely play an important role as role models, advocates, and change agents, active involvement of male leaders in championing and driving the gender diversity agenda is critical. Diversity programs that are “led by the women, for the women” are limited in their impact. If male leaders don’t get involved, progress will stall.

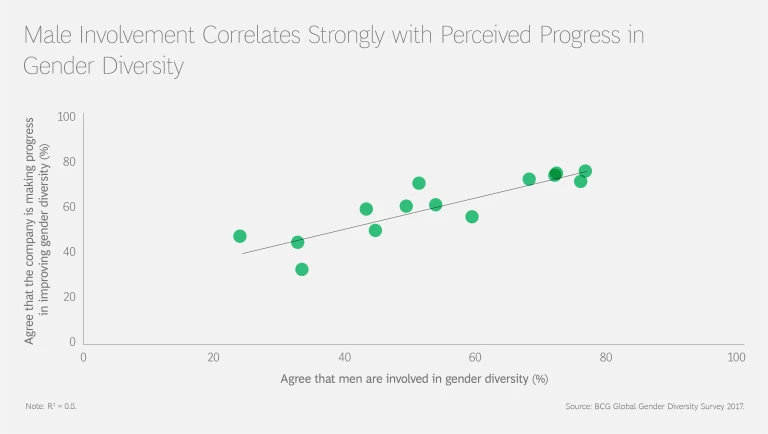

Across the Canadian companies that BCG surveyed, there was an 80% correlation between the involvement of men in the gender diversity programs and the view that progress was being made.

Simply put, when it comes to gender diversity, senior male leaders need to step up and lead the change. For example, they should be open to changing their perceptions about the obstacles women face and the interventions needed to address them.

A Call to Action for Canadian Companies and Business Leaders

Senior business leaders should ask the following questions:

- Have we articulated the business value of gender diversity for our company? Do leaders believe it?

- Do we have clear objectives for gender diversity in our company?

- Do we really understand the obstacles women face in our workforce—through data and analysis rather than gut-level hunches?

- Do we have a portfolio of priority initiatives tailored to the specific obstacles our women face?

- Are we being programmatic and rigorous in our approach to implementation?

- Are the male senior leaders involved in driving gender diversity?

Leaders can use these questions to assess where their company stands in terms of maturity for gender diversity—nascent, committed, or persistent—and follow the lessons learned from persistent companies to advance progress.

Read More

Getting the Most from Your Diversity Dollars