At many organizations, problems scaling agile can be traced to problems scaling agile coaching.

Organizations are accelerating their transformation to digital to enhance their speed and data-driven decision making, and to support working in new ways. Adopting agile ways of working is one o f the keys to a successful transformation . Using agile coaches helps cultivate the new behaviors that unleash agile and unlock productivity. Agile coaches help teams put theories into practice by weaving agile ways of working into daily routines. And they guide teams to adjust agile practices to their specific needs and measure outcomes so that teams can assess their progress and take steps to improve.

Yet many organizations struggle to get agile coaching right. The coaches themselves aren’t usually the problem. More often than not, problems arise because organizations adopt the wrong agile coaching approach. When that happens, new ways of working stall, agile teams that started out collaborating well revert to old behaviors, and costs add up without producing the intended results.

Dozens of our clients have easily taken over running this approach themselves after an initial setup period, with no need for ongoing outside help.

Organizations can overcome these problems if they treat agile coaching as a business operation. In the approach, coaching is coordinated across the entire organization to maximize available coaching resources, and it consists of three parts:

- Coaching as an Investment. Coaching assignments have preset goals and time frames, which helps with planning and budgets, making agile coaching resources easier to scale.

- Coaching as a Pack. Coaches at all levels work together as a single entity, or “pack,” which helps improve team productivity.

- Coaching Through Interventions. Coaches “intervene” or work with teams in quick sprints as needed and work from a single agile coaching playbook that is updated with learnings from previous interventions.

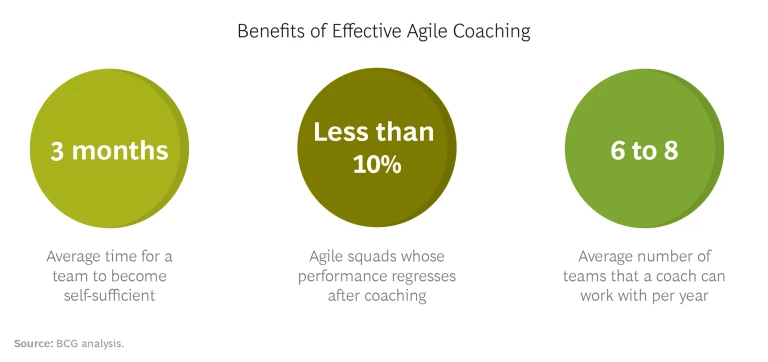

Dozens of our clients have easily taken over running this approach themselves after an initial setup period, with no need for ongoing outside help. Teams new to agile have used it to become self-sufficient in about three months, with less than 10% reverting to previous nonagile behaviors. In the approach, coaches can work with two teams at a time and an average of six to eight teams a year. In addition to making coaches more productive, the method yields more engaged employees, better collaborations between business and technical teams, and more effective use of coaching resources. Most important, organizations develop a rigor that allows them to quickly gain the full benefits of agile at scale.

Signs That Agile Coaching Isn’t Working

When agile doesn’t scale, poor coaching might not be the first thing that comes to mind. But the signs are there. When organizations shift from running a few pilots to expanding agile throughout the enterprise, a number of common pitfalls can create setbacks. Coaches stay with a team too long or see themselves as lone wolves. Budgets aren’t set, metrics aren’t tracked. Agile methods are either inflexible or inconsistent, or parts of the business choose not to participate. (See the sidebar.)

Warning Signs Your Agile Coaching Is in Trouble

Coaches overstay their usefulness. If clear goals are not defined at the beginning of a coaching sprint, coaches may stick around well after a team has become self-sufficient instead of moving on to help a new group get its agile bearings. That locks up coaching resources, which limits flexibility and adds to coaching costs.

Coaches are not given sufficient direction. Too often, companies do not give coaches enough of a mandate for what they are expected to do. As a result, coaches are left to go it alone and train teams based on their own interpretation of agile practices. But implementing agile at scale is a complex undertaking that requires a unified approach to coaching at all levels, and in the case of multinational companies, across global tribes operating in multiple locations. To be successful, coaches must operate as part of a pack that works together to coach the entire organization, from the C-suite agile sponsor to junior software developer.

Budgets aren’t set. Coaching should be part of the investment that companies make in adopting new ways of work. Yet companies don’t always include it in their agile transformation budget, which can delay the transition. It can also lead teams to hire coaches on their own, potentially contributing to further fragmentation of the operating model, rather than follow the organization’s established coaching playbook.

Metrics aren’t tracked. Measuring the adoption rate and maturity of agile methods and practices makes it easier to plan how coaching resources will be used. Yet, a surprising number of organizations overlook this basic building block of coaching operations. Tracking should include the teams currently running agile, those being formed, and those that may be needed in the future. To form the most accurate picture, monitoring should also measure improvements to delivery productivity.

Agile methods are inflexible or chaotic. Too often, coaches forget the forest for the trees. Instead of helping teams understand how to apply general agile practices to a variety of circumstances, they zoom in on methods that are overly prescriptive or complex, that relate only to the technical side of new ways of working, or that apply only to a few, isolated agile teams. In other cases, coaches operate as lone wolves outside the purview of the coaching operation. When that happens, organizations can end up with a different version of agile for every team that uses it, which can wreak havoc on coaching and agile practices.

The business opts out. When agile begins as an IT or software development initiative, other parts of the organization may pigeonhole it as a technology fix and dismiss it. When the time comes to roll out agile across the business, that attitude can lead to low engagement beyond pilot groups, few business product owners who want to be involved, and ultimately, poor alignment between agile and business goals. If coaches can’t engage senior stakeholders to help design, launch, and optimize agile teams of teams, implementing agile effectively may be a lost cause.

Other obstacles can trip up coaching. Having too few coaches creates bottlenecks that delay adopting agile across the organization. This can prevent teams from getting the support they need to embrace new ways of working. Moreover, organizations often struggle to build adequate coaching capabilities in-house, leaving them to depend on often expensive external coaches for too long. In addition, coaches have to ensure that agile teams function as part of the broader effort to scale agile practices. That puts pressure on them to be consistent in how they coach individual teams and how they interact with other teams and the broader organization.

The aspects of agile that the training will target are determined prior to the engagement, along with the performance level the team needs to reach to be considered self-sufficient.

Our Approach to Agile Coaching Operations

Approaching agile coaching as an operation solves the challenges that stop agile from scaling, without the need for additional resources. It’s simple to expand, flexible enough to support teams with a range of agile experience, and helps coaches flourish in their roles and create a lasting impact.

The approach consists of three related aspects: coaching as an investment, as a collective, and as an intervention. (See Exhibit 1.)

Coaching as an Investment. In the first part of the approach, coaches are “invested” to train teams on some aspect of agile for a finite length of time. (See Exhibit 2.) The aspects of agile that the training will target are determined prior to the engagement, along with the performance level the team needs to reach to be considered self-sufficient, able to continue to improve on its own without regressing to previous behaviors. The assignment begins once the conditions for success are spelled out and the team deemed “coachable,” with the majority of key roles in place and a clear roadmap and outcomes. Most coaching engagements last three to four months. Our client work has shown that one coach can support two new-to-agile teams simultaneously. We have also found that when teams are self-sufficient, organizations can operate with one coach for ten to 18 teams, or approximately 100 to 150 total employees working in teams of eight to 15. After an assignment, coaches act as mentors, and teams receive additional coaching should the need arise, typically if their performance degrades, or if material changes to the team structure are required, or if the team is reoriented to address a different issue and needs additional support.

Having clear exit criteria for a coaching engagement ensures that coaches are deployed where they have the most impact and stay with teams only as long as they are needed. This reduces the total number of coaches needed, thus reducing overall coaching costs. Clear guidelines for how long coaching engagements last and metrics for success also make it less likely that external coaches will remain embedded within teams too long, which can add to costs.

Coaching as a Pack. The second key part of the approach is treating all coaches— whether in-house or external—as a single community or collective, one that carries out the organization’s agile operating model and ways of working. The community comprises team coaches of various levels of experience and seniority who operate as a collective or “pack” and are led by an executive coach.

A coaching pack teaches agile practices across teams of teams, as well as to business functions and departments.

The enterprise coach is typically the most experienced member of the community, and the lynchpin of coaching operations, especially when companies are transforming to agile. The enterprise coach has the seniority, presence, and management expertise to influence leaders and to manage and coordinate coaches. The enterprise coach helps decide where coaching interventions are needed and keeps track of the teams being coached and how training is progressing. Enterprise coaches manage coaching budgets, train junior coaches, and serve as the community’s main contact with senior business leaders. They are well-versed in agile practices, including the organization’s own flavor of agile, and have sufficient experience and gravitas to influence senior stakeholders and to coach leaders and coaches. They typically remain in the position to provide continuity.

Team coaches move from team to team as squads meet performance goals and mature. A coaching pack teaches agile practices across teams of teams, as well as to business functions and departments. Coaching packs use the same agile practices that they teach, including working in sprints and holding daily standups.

Coaching Through Interventions. The final part of the operations approach is the way in which agile coaches work. They use a single set of systematic, trackable actions—we call them interventions—that are codified in an agile coaching playbook developed by the organization’s coaching community. Training from a single coaching playbook ensures that coaching is explicitly defined, transparent, and helps an organization’s agile ways of working to coalesce, improve, and evolve. It also helps teams learn and apply agile practices to a range of circumstances. The lessons they learn are added to the playbook and organization’s general body of agile knowledge and processes for future reference.

The coaching playbook is especially useful when coaches run two-week “sprint” interventions with teams that need to improve a specific capability or to address performance gaps. The coach then chooses from hundreds of “battle-tested” interventions in the playbook that target that capability or performance gap, and designs a sprint plan based on it. At the end of the sprint, the coach and team evaluate the impact of the intervention. Reflecting on the effectiveness of the intervention and creating new ones also helps propagate and improve the catalog of interventions.

In the early stages of rolling out agile at scale, it’s especially important for coaches to work as a collective so they can coach to the playbook while actively improving it.

Requiring all coaches to follow the same playbook for interventions has other benefits:

- It demystifies coaching, moving it away from the idea of acolytes following a guru and toward imparting a standard set of skills and ways of working.

- It improves an individual coach’s confidence in their ability to lead change.

- It provides a consistent path for teams new to agile become self-sufficient, which boosts overall effectiveness.

- It accelerates training by having a single, consistent coaching method for both internal and external coaches.

Intervention coaching helps an organization put sufficient team-level coaches in place to make the transition to agile at scale at a pace that’s right for the company’s goals and needs. In the early stages of rolling out agile at scale, it’s especially important for coaches to work as a collective so they can coach to the playbook while actively improving it.

How to Adopt the Agile Coaching Operations Approach

To adopt this approach, an organization may need to rework its existing agile-coaching function. That means reassessing which skills coaches need, what their career paths might be, and how their performance will be measured. It could entail a workforce planning review to determine whether there is sufficient in-house talent to implement a new coaching model or if, for a period, the organization needs to supplement existing internal coaching with external contractors.

To get the full value from the approach, organizations may need to make the following three complementary changes:

Adjust how coaches are deployed and managed. A new approach to coaching may require creating or reorienting other aspects of agile operations, including the organization’s agile impact center, sometimes referred to as the agile center of excellence or agile accelerator. Organizations may also need to rework how they recruit and train coaches, as well as coaching-related performance management, incentives, and budgets.

An organization should avoid piloting agile coaching—and agile in general—as a side project or in a single department such as IT.

Launch an executive-coaching program. When an organization undertakes a significant agile transformation, leaders have to commit to working in new ways, including working with agile coaches. Since leaders have to adopt new behaviors to do that, we recommend launching an executive-coaching program. Such a program can be led by an agile-savvy leadership coaching specialist and the agile coaching pack. Getting leaders on board early in the process sets the tone for lower-level leaders. It can also ward off potential negative behaviors at the top that could doom agile at scale from the start.

Don’t make agile coaching a side project. To ensure that the transformation is across the business, an organization should avoid piloting agile coaching—and agile in general—as a side project or in a single department such as IT. It doesn’t work. At its core, agile is a set of principles for establishing teams that make change happen and to improve operations through behavioral change. Those methods are flexible enough to apply to a range of situations throughout the business. Pilots could target strategic operations or book of work, led by the most experienced agile coaches and staffed with a cross section of personnel from a variety of previously siloed departments. Dedicate a sizeable enough investment to getting a new agile coaching approach off the ground.

The transition to agile represents a fundamental change to an organization’s operating model. One of the chief differences between implementing agile at scale and other operating-model changes is the need to change culture and behaviors. Effective agile coaching can make the change more effective and scale faster. Adopting the operations approach of coaching as an investment, community, and intervention transforms agile from a scaling problem to a powerful agent of change.