The transition to agile, especially agile at scale , can be difficult. It’s one thing to help a small group adopt daily standups, sprints, and other agile practices. It’s something else entirely to steer an organization of hundreds or thousands of people toward shared, impact-driven outcomes while simultaneously giving smaller working groups autonomy over how they reach those goals.

The tie that binds everything together is effective governance. BCG’s business review approach for agile governance weds strong alignment on outcome-oriented strategies with the high degree of autonomy required for teams to deliver value at speed and at scale.

At the heart of the approach are annual business reviews (ABRs) and quarterly business reviews (QBRs) as well as a framework of activities that cascade from them. As a senior executive at one BCG client says: “We set the vision and define the outcomes that connect what we do to our purpose. Then the teams show us the way.”

Although other agile-governance frameworks exist, we have found that when companies use the business review approach they create a stronger link from strategy to execution through an “ unbroken chain of why ” and derive more value from their teams. Benefits include better and more timely business results, less bureaucracy, more engaged employees, and improved tracking of progress toward goals.

Where Agile at Scale Breaks Down

To implement agile, leaders may adjust a company’s organization structure to form agile squads (teams) and tribes (teams of teams) , create new job roles, and change from more traditional waterfall-style execution to scrum or kanban. But if they don’t change governance—how decisions are made and risks are managed—they’re left with the parts but not the whole.

In our client work, we’ve seen several common indicators of agile governance that’s less than ideal:

- A department, function, or entire company that implements agile but doesn’t realize the expected benefits

- Leaders who become frustrated because they don’t have sufficient transparency on the status of the work the agile teams are doing

- Little or no obvious link between the business strategy and teams’ priorities and scope of work

- Decision making that is not transparent, so individuals aren’t part of the process and consequently are less engaged and don’t understand why they do the work they do

- Agile teams that spend too much time justifying their work in order to get projects funded

- Priorities that constantly shift because of conflicting feedback from multiple decision makers, leaving teams less time to concentrate on the actual tasks

- Work that is focused on milestones, deliverables, and outputs rather than impacts

- Squads representing separate silos within a tribe that don’t collaborate to deliver on goals

- Companies that engage in agile theater rather than embrace true agile concepts, replacing the old management bureaucracy with a new one that’s just as complex and rigid

L eaders can make or break the governance process. If they micromanage, it stifles creativity and innovation and prevents agile teams from feeling empowered and accountable for outcomes. But if leaders aren’t involved enough, teams can end up too focused on the platforms or solutions that are needed to deliver outcomes rather than on the outcomes themselves.

Using the Business Review Approach to Achieve Alignment and Autonomy

The linchpin of BCG’s business review approach is creating an unbroken chain of why from strategy to execution. Leaders and teams use ABRs and QBRs to analyze the progress that’s been made toward the goals outlined in the previous period, align priorities to strategic goals, and shape delivery roadmaps. Each review serves a distinct purpose.

The linchpin of BCG’s business review approach is creating an unbroken chain of why from strategy to execution.

In ABRs, senior leaders review strategic objectives, past results, and major initiatives that are starting or wrapping up in order to shape delivery objectives for the next one to three years. They set long-term priorities and goals for agile tribes, each of which may consist of several squads. Senior leaders also use ABRs to set or adjust tribe budgets for the next 12 to 18 months and optimize spending across multiple tribes.

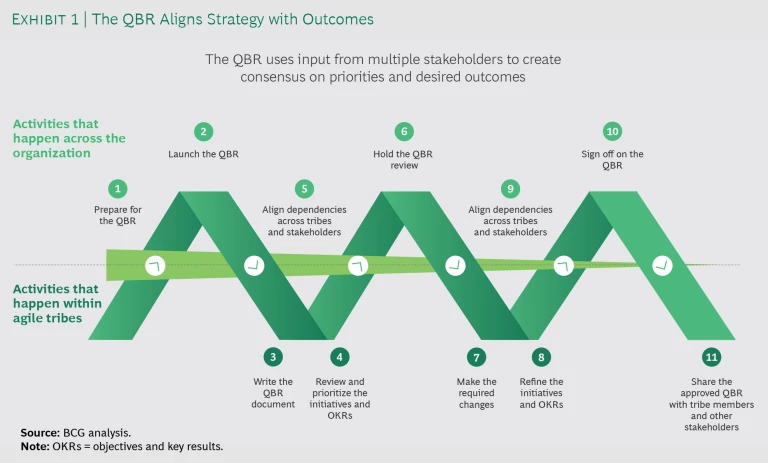

In QBRs, agile tribes review the progress they made toward stated goals over the previous three months and use that to start, reshape, or halt initiatives for the coming three to nine months. (See Exhibit 1.) They match priorities to available capacity and align dependencies in order to maximize outcomes in the coming quarter. During the QBR process, tribes also align horizontally with other tribes to refine the scope of work, agree on how they can help one another deliver on targeted outcomes, and resolve potential conflicts. These tribe-to-tribe alignments typically occur at several points during the QBR process.

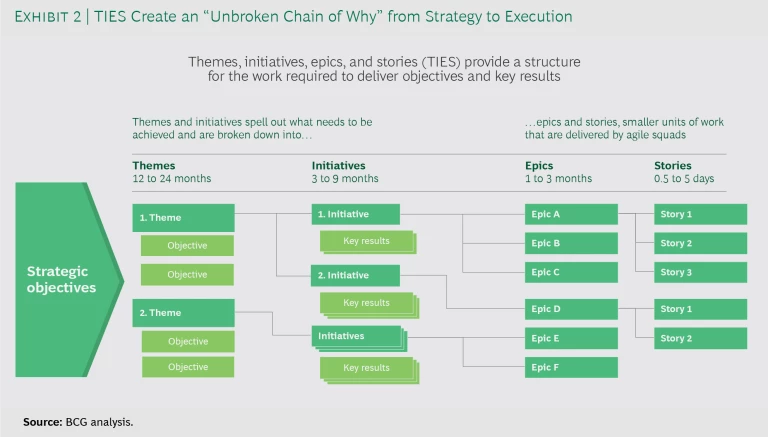

A company or business unit can use ABRs and QBRs to break down long-term strategic goals that may take several years to attain into increasingly granular themes, initiatives with specific objectives and key results (OKRs), epics, and stories—and course correct as the work progresses (see Exhibit 2):

- Themes are large blocks of work with a high-level scope and time-specific outcomes that link to at least one strategic objective and span 12 to 24 months. A theme for a bank, for example, could be to improve the user experience, reach new customers, and lower costs by reducing inquiries to call centers and branch offices through digitized processes for credit card and home-loan applications. Agile tribes and other stakeholders collectively define themes and objectives that are validated by an executive committee or change prioritization board.

- Initiatives are smaller units of work that contribute to delivering a theme. They typically last three to nine months and have defined key results. In the previous example, if the objective is to improve user experience and reduce costs, a related initiative could be to add a feature to the bank’s mobile app that automates the application process for a credit card or home loan. Tribe leadership, agile squads, and other stakeholders propose, prioritize, and select initiatives, and the agile-tribe leads and business-unit sponsors sign off on them.

- Epics are the work that has to happen in order to deliver the key results defined in an initiative. Continuing the bank example, if an initiative is to automate home-loan applications, a related epic could be to define the changes and software code required to move the application process online by creating a pilot for a simple home-loan product. Epics typically are accomplished in one to three months by one or more squads. In QBRs, tribes plan epics for the next one or two quarters and refine roadmaps for epic-level activity over the next four quarters.

- Stories are small, testable work activities taken from epics that one squad can accomplish in a single sprint of up to five days. After themes, initiatives, and epics are confirmed in a QBR, the product owners and squad members define the related stories.

BCG agile-at-scale clients have used our business review approach to translate long-term strategic goals into clear priorities and measurable outcomes for hundreds, thousands, and in some cases, tens of thousands of people.

At one client company, we helped a tribe of 100 people break down its strategic vision into four themes of 12 to 24 months and subdivide those into 20 initiatives of 3 to 9 months. The client’s leadership and agile teams used QBRs to match priorities to delivery capacity, taking into account available resources and delivery dependencies. Leadership and agile teams sketched out epics related to the initiatives at a high level, but squads refined the epic details and stories. Within three weeks, the changes helped the client pivot to a different scope of work without requiring additional budget. It brought the tribe’s work more in line with the overall strategy and priorities of its division, reoriented goals from outputs to outcomes, generated ideas for initiatives to start or end, and boosted employee engagement.

It’s worth noting that while the business review approach provides strong governance over what work is done, it’s just as important for organizations to institute a robust system for guiding how that work is achieved. Chapters, centers of excellence, and design authorities are effective means of ensuring that work follows best practices, standards, and controls, which lead to better and more productive delivery of the overall objectives defined in the business review process. The success of ABRs and QBRs also depends on making significant changes to how an organization approaches funding.

How to Be Successful with Outcome-Oriented Agile Governance

We’ve identified a number of guiding principles that could be helpful to consider when starting out.

Articulate strategic objectives. These objectives serve as a reference point for decision making and provide a sense of purpose up and down the chain of why. People at every level need to know why they are doing what they’re doing, so don’t be shy about sharing the strategy with them.

Get specific. In discussions and memos or narratives used to describe initiatives and key results, be specific about the expected outcomes, how they link back to the overall strategy, and how the impact on customers, users, and stakeholders will be measured. Include details of what is and is not in scope, outcomes that need to be delivered and why, open questions, and dependencies. Show a clear link to strategy through the overarching themes and objectives.

Adhere to agile principles. If you’re adopting agile for the first time, resist the urge to command and control from the top. Leaders need to articulate the what and the why, then get out of the way and let tribes and squads figure out how to execute and deliver the desired impact.

Be inclusive and transparent. Involve members of tribes, squads, and other stakeholders in business reviews from the beginning. Ensure that representatives from the affected business units and central functions, including strategy, operations, and technology, are engaged. Being inclusive helps spark ideas and drive innovation. It builds trust and consensus on decisions and increases the likelihood that the solutions being delivered will yield the expected outcomes.

Use strategy to define tribe and squad missions. By their nature, themes and initiatives are relatively short term. When defining a tribe or squad’s mission, then, it’s better to use more long-term criteria, such as overall business purpose or strategy, which can support themes and initiatives on an ongoing basis.

Don’t decide outcomes ahead of time. In business reviews, stay open to ideas and constructive challenges that bubble up as discussions progress, including pain points that need to be addressed, suggestions for new initiatives, and novel ways of doing things. Often the best ideas come from frontline personnel.

Avoid taking on too much. Committing to an excessive number of priorities can create unrealistic expectations for the coming quarter or year, move the focus away from key outcomes, and lead to an increase in unfinished works in progress. The ultimate objective is to deliver the best value given the available capacity. Our experience has shown that focusing on a limited scope of work improves effectiveness and delivers more long-term value.

Base decisions on data. Instead of relying on gut feelings or instinct, use data to make decisions, including which themes and initiatives to prioritize and how to define what constitutes successfully delivering objectives and key results. Use dashboards and other trackers to measure outcomes and help tribes and squads understand how they’re doing. In some cases, the data that’s needed to measure success may not exist, which means you may need to invest in ways of defining, measuring, and analyzing it.

Agile at scale can be complex and affect so many people that consolidating decision making at the top may seem like the way to go. But top-down management is the antithesis of agile. We’ve found that companies derive far greater benefits when they adopt an outcome-oriented system of governance that aligns activities to strategies while giving teams who deliver the work the freedom to decide how to reach their goals.