This article was developed in collaboration with Cara Plus.

Here’s one crisis: organizations across industries are experiencing massive talent shortages, with 75% of US employers reporting difficulty finding the skilled talent they needed in 2023—a 17-year high. Here’s another: more than 600,000 people are released from US state and federal prisons each year and seek job opportunities, yet they, along with millions of additional justice-involved individuals, are unemployed at rates far higher than the national average.

And here’s a solution to both crises: fair-chance hiring.

Fair-chance job seekers are people who have been involved with the criminal justice system, whether convicted of a crime, incarcerated, or arrested but never convicted. These individuals—one in three US adults—are more likely than the overall population to be actively looking for work, but they have little to no access to quality employment opportunities because of their background.

But there’s good news. The data shows that fair-chance hires perform as well as, or better than, their peers who have no history of justice involvement. (See “Characteristics of Fair-Chance Job Seekers.”)

Characteristics of Fair-Chance Job Seekers

…are eager to work and actively seek opportunities. Research from the Prison Policy Initiative shows that formerly incarcerated people aged 25 to 44 exhibit higher labor-market engagement, with 93% actively employed or seeking work, compared with 84% among their peers in the general population.

...have high retention rates. Research shows that individuals with criminal records have longer job tenure and are less likely to quit their jobs than others. So, fair-chance hiring can generate significant economic impact via improved productivity and savings on recruitment and training expenses.

…contribute to a strong internal company culture. Ninety-six percent of workers said they would prefer to work for an organization using fair-chance-hiring practices, according to a 2022 survey by Indeed and Kickstand, and other research shows that enacting these policies generates loyalty and engagement among all employees.

… are, once hired, less likely to reoffend. Individuals who are employed two months after reentry are about half as likely to recidivate as those who are unemployed, according to Rand. And, those with conviction records who have since successfully completed a vocational or educational program have a risk of future conviction that is indistinguishable from that of the general population.

Thoughtful hiring initiatives are underway, with two primary motivations:

- Fair-chance hiring presents a compelling opportunity for employers to fill critical talent needs with a strong, largely untapped talent pool.

- A growing number of organizations see fair-chance hiring as a social imperative and an essential part of their inclusivity efforts.

In 2023, BCG partnered with Cara Plus (a division of the workforce development organization Cara Collective) to study employers implementing fair-chance hiring, building on

in-depth research

conducted with the Corporate Coalition of Chicago. We observed how these organizations, representing a variety of sizes, industries, and missions, designed and executed their fair-chance-hiring initiatives, focusing on the journeys they took to get to where they are today—journeys that can inspire and guide other organizations.

How Organizations Can Put Fair-Chance Hiring to Work

Through our research, we uncovered themes common to organizations that have successfully implemented fair-chance hiring. We found that most organizations start with a handful of hires—sometimes through a pilot, although often less formally—and then expand their initiative, building on their momentum and incorporating what they learn. We’ve distilled their experiences into four areas:

- Building the Foundation

- Assessing and Addressing Risk

- Rewiring Hiring

- Onboarding and Retaining

Building the Foundation

Determine whether fair-chance hiring is right for your organization. For all of the companies we researched, fair-chance hiring started with needing to solve a problem. Always, this meant meeting a business need; often, it also meant satisfying a social imperative.

For example, Toyotetsu, a Japanese automotive parts supplier with a large US division in Texas, needed employees. Its Texas division was located in a semirural area, in an industrial park that also housed 24 competitors, upping the ante for Toyotetsu to attract sought-after talent. In 2018, when unemployment was low and the company was struggling to recruit and retain frontline workers, it hired its first fair-chance job seeker—who ended up outperforming other employees, prompting Toyotetsu’s leaders to expand its hiring strategy to include fair-chance candidates.

For companies that already have inclusive policies, fair-chance hiring can be a fitting initiative. Nehemiah Manufacturing, a consumer goods manufacturer based in Cincinnati, is a prime example. Daniel Meyer founded the company with social impact at its core. His vision was simple: to develop a business in the inner city that could employ members of the surrounding community. Two years after the business was launched, Meyer was working with a local nonprofit employment agency and was asked to hire someone with a past felony charge. That first hire was so successful, Meyer’s vision quickly expanded and Nehemiah immediately sought additional employees with similar backgrounds.

Identify a change champion. When it comes to fair-chance hiring, passion and commitment are nonnegotiable. Many organizations we spoke with can trace their fair-chance effort to a single person who believed in its potential and then saw it through—either directly or by designating others to lead the charge.

The change champions we observed were familiar with the needs of the business and were typically in senior roles, demonstrating the importance of the issue. Part of their job was to shift the discussion from “Can this happen?” to “How can we make this happen?”

Leslie Cantu became Toyotetsu’s change champion after the company’s first fair-chance hire excelled. Cantu, the assistant vice president of administration, wondered how many other hard workers the company was missing out on by ignoring the justice-involved population. To explore this, she and a Toyotetsu attorney began brainstorming how to resource the program. She developed much of the program’s initial design and strategy, met with reentry centers to learn more about interested candidates, and set up weekly information sessions with probation officers and reentry centers—work that proved instrumental to the program’s long-term success. And it paid off: in 2023, its seventh year as a fair-chance employer, Toyotetsu counted more than 250 fair-chance hires among its employees.

The first change champion at San Francisco–based Checkr was its CEO, Daniel Yanisse. After touring a Bay Area prison, he realized that the company’s background check services had a disproportionately negative effect on the justice-involved population. To counterbalance that impact, he was motivated to make Checkr’s first fair-chance hire and thereby show that justice-involved employees could be successful team members.

Time and again, we see the fair-chance talent we’ve welcomed to Checkr become highly engaged, ambitious, and successful employees. — Daniel Yanisse

In fact, Yanisse has doubled down on fair-chance hiring by bringing in a justice-involved executive to scale fair-chance hiring and thought leadership at Checkr. The company has employed more than 50 justice-involved individuals in a variety of roles since its initiative began and has committed to educating Checkr customers and other businesses about the benefits of fair-chance hiring. “Time and again, we see the fair-chance talent we’ve welcomed to Checkr become highly engaged, ambitious, and successful employees,” Yanisse has said.

Engage senior leaders and direct managers. Across the board, getting a champion is just the start: C-suite members, HR leaders, and the direct managers of fair-chance hires are all critical in setting an organization’s tone on fair-chance hiring. While it is important that they share the company’s commitment, we found that embracing fair-chance hiring did not always start this way; often, it required intentional change management.

At Toyotetsu, Cantu proved the strategic benefit of fair-chance hiring to the executive team after a few initial hires. She tracked performance data on how many people Toyotetsu and other organizations had hired and retained, showing that fair-chance hires constituted a viable and successful talent pipeline. She also shared the stories of Toyotetsu’s initial hires and the impact employment had on their lives.

Recognizing that much of the day-to-day operational changes involved in fair-chance-hiring fell on managers, Toyotetsu also provided training focused on the unique challenges that these employees faced and broke down any remaining resistance to the initiative by showing how it helped the individual, community, and company. The company also encouraged open lines of communication between the managers and their supervisors. By focusing on a shared goal—being able to recruit better candidates who were going to stay longer—it was able to bring managers onboard.

Assessing and Addressing Risk

Consider the risks, real and perceived, that the organization will face. Some of the biggest challenges organizations must navigate are regulations and risk—real or, more often, perceived risk.

At JBM Packaging, an Ohio-based ecofriendly-packaging company, long-standing employees were among the most doubtful. JBM’s approach was to “humanize those with records” by taking employees on educational visits to correctional institutions and other companies that had hired fair-chance candidates. Leaders also encouraged employees to reflect on mistakes they themselves had made and recognize similarities to fair-chance candidates. Seven years later, JBM had employed 109 fair-chance individuals.

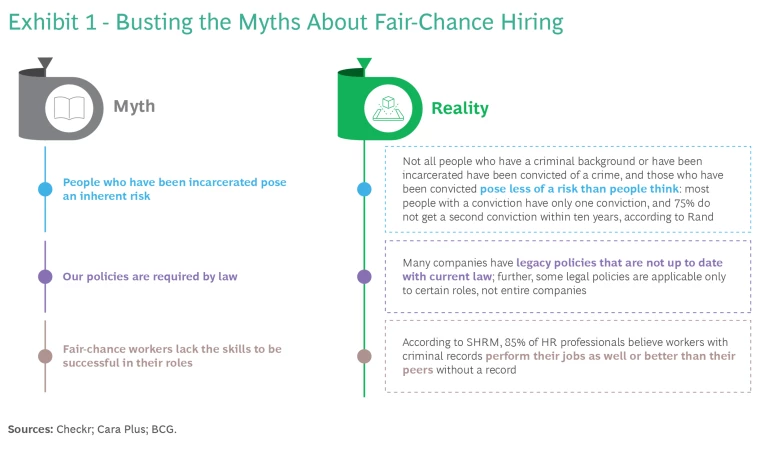

Ken Oliver, a vice president at Checkr, pointed to myths related to fair-chance hires. There is, he said, “a danger in us becoming a second judge and jury and perpetuating stigma and bias rather than deconstructing it.”

Establish risk-appropriate workarounds for restricted or regulated roles. In certain industries, government-mandated or corporate legal and regulatory restrictions limit the roles that justice-involved individuals are allowed to hold. Even so, employers found ways to work with fair-chance hires by examining how they could humanize hiring by revamping their background-check processes and identifying roles for fair-chance candidates.

Financial institutions, for example, are subject to the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, which lists disqualifying offenses with varying levels of exclusion. Despite being federally regulated, one industry player did not want to exclude strong fair-chance talent from its candidate pools, so it began conducting individualized applicant assessments. These discussion-based assessments allow it to better understand the context surrounding each candidate’s background on a case-by-case basis, so that it can examine applications in line with regulations while identifying qualified candidates.

Of course, some employers have few or no regulatory limitations on hiring, so they use their own judgment on what makes sense for their business. For example, one commercial real estate company began fair-chance hiring by distinguishing between client-facing roles (where contractual stipulations required it to be stricter about conviction and drug requirements) and internal roles (where it could be less stringent about record, education, and drug requirements).

And Toyotetsu, which once did not hire individuals with violent convictions, has since softened that requirement. Today, Toyotetsu considers such candidates if they have 12 months of continuous employment before they apply; it helps them satisfy that requirement through community partners like Goodwill.

Rewiring Hiring

Create welcoming job descriptions. Some organizations realized that fair-chance candidates were not applying because they assumed they were unwelcome. The University of Chicago, for example, in an effort to more intentionally attract fair-chance candidates, updated the language on its job descriptions, detailing how its background policy worked so that justice-involved individuals knew they were eligible. The language was updated to read: “All offers of employment are contingent upon a background check that includes a review of conviction history. A conviction does not automatically preclude University employment. Rather, the University considers conviction information on a case-by-case basis and assesses the nature of the offense, the circumstances surrounding it, the proximity in time of the conviction, and its relevance to the position.”

Make advancement pathways clear from the start. Individuals with previous involvement in the criminal justice system are interested not only in landing jobs but in performing well in those roles, enabling advancement into higher positions. More than 80% of HR and business leaders said fair-chance employees performed comparably to or better than their counterparts, signaling both an ability to exceed expectations in their starting role and the capacity to progress to other roles.

Chicago-based Freedman Seating, which manufactures seats for various forms of transportation, has taken steps to make the requirements for promotion more transparent and to shield fair-chance hires from any subjective bias. It has created formalized advancement programs, and when an employee does not get a sought-after promotion, Freedman makes it a priority to explain why and to detail what the individual can do to improve their chances in the future. This helps develop employees—both fair-chance and “traditional”—over the long term and helps Freedman retain strong talent by aligning incentives and motivating upward progression.

Revamp sourcing, screening, and interviewing. To source hires, Freedman Seating took an active approach to fair-chance recruitment by leveraging the Safer Foundation, a nonprofit that provided reentry assistance, training, and job placement for justice-involved individuals. Nehemiah, too, worked with an outside agency to find permanent employees, using a temp-to-hire approach to staff workers for three months. During that time, Nehemiah was able to assess job performance and fit, while temporary employees could determine whether they liked the job. If both parties were satisfied, the job became a permanent position.

Onboarding and Retaining

Find ways to help fair-chance hires address new challenges at and outside of work. In each case we studied, we found that organizations had thought smartly about how to set up fair-chance hires for success. While they did not always start with a plan to train or support fair-chance talent any differently (specific approaches often came about organically), they found that doing so paid off.

Toyotetsu implemented a mandatory new-hire bootcamp through which new employees learn about the manufacturing industry, key terminology, and the organization’s expectations. Upon completion, new hires are provided with uniforms and steel-toed boots. They are then matched with coaches to help them navigate their first few months on the job and connect them to supportive services to help with basic needs, including housing, transportation, and food insecurities. The company has found that training and job coaching have a significant impact on retention.

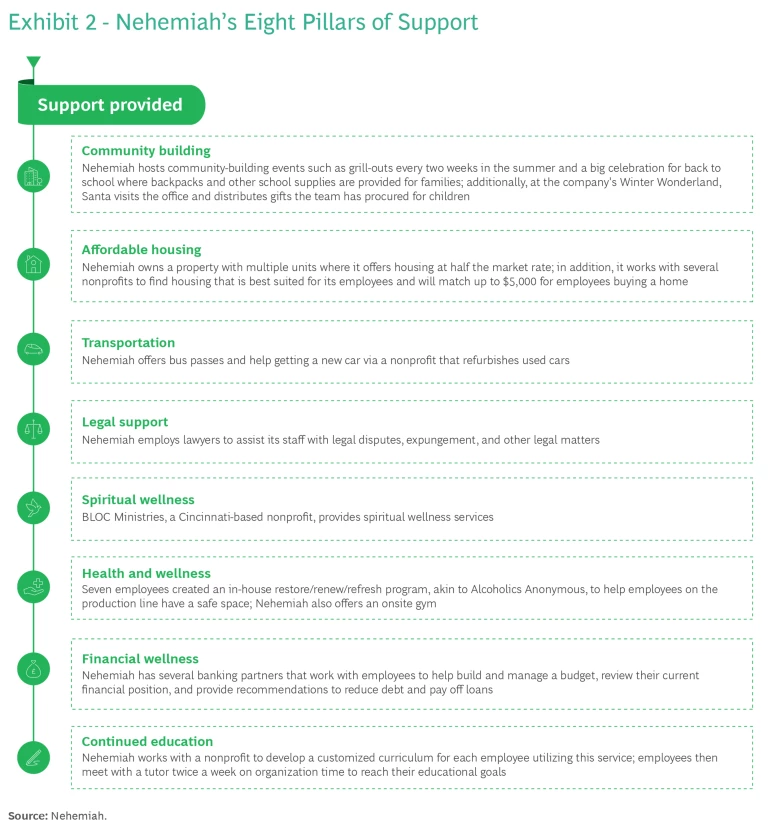

Nehemiah adjusted its approach in the face of a challenge: its fair-chance hires stopped showing up for work, even when their performance was strong. Eventually, the company was able to identify the cause: the systemic challenges that its fair-chance hires faced. It implemented a custom-fit solution by hiring social workers, who were able to help the staff understand and address the barriers that can prevent fair-chance employees from maintaining attendance, like unstable housing and lack of child care or even unexpected probation or parole requirements.

To scale this solution, Nehemiah’s CEO calculated the cost of the employee turnover and invested a portion of that cost into funding additional social workers and other services. As its fair-chance employee count grew, Nehemiah increased the number of days social workers were available until they had a full team. As a result, turnover shrunk to 15%, significantly lower than that of competitors (whose turnover could exceed 50%). The experience enabled holistic support for fair-chance hires and contributed to a web of essential and supplementary wraparound services that have turned into Nehemiah’s eight pillars of support.

Engage both nonprofit and public partners. In nearly every case, organizations did not go it alone. Rather, they partnered with outside organizations—often nonprofits—to provide services or expertise that they did not have.

When Toyotetsu recognized that its fair-chance employee population had grown quite large, it decided to outsource its wraparound supports. It connected with Chrysalis Ministries, the fair-chance expert in the community. Chrysalis provided one-year, on-the-job retention coaching. Today, Toyotetsu also collaborates with Workforce Solutions Alamo, job coaches, and other community partners to meet specific needs, such as job readiness training and transportation stability.

Other companies tried bold new moves that later required some strong pivots.

Nehemiah, for example, sought to address the housing need identified through employee conversations. At first, it “flew solo”: Nehemiah bought apartments to offer housing for new hires. What initially seemed like an easy solution turned out to be unsatisfactory: some employees didn’t want to live near their coworkers or in the area where the apartments were located.

Creative, multimodal solutions can help maximize engagement with fair-chance employees.

Meyer was quick to acknowledge the lesson but remained committed to addressing the identified need. The company now offers two-year transitional housing at a submarket rate, while providing a first-time home-buying program in which the company matches $5,000 in cash for a first home purchase. It also integrates the housing offer with other support services provided by local organizations: used-furniture purchasing, legal support, job-readiness training, and educational services and extracurriculars for children. Given that Nehemiah has been working with many of these nonprofits for over a decade, it now has fine-tuned relationships and can count on support.

Freedman Seating offers housing and transportation assistance through WorkLife Partnership, an organization that helps companies provide additional support services to employees. In the early days of the program, Freedman found that employees were not engaging with these services; it determined that awareness was low. Once the company began to better market the services through lunch-time gatherings, 90-day check-ins, and shadowing for new employees, uptake increased.

Creative, multimodal solutions to maximize engagement are especially important given that many fair-chance employees are deskless workers who require engagement channels outside the normal email-based communications.

Continue to foster an empathetic culture. To ingrain fair-chance hiring, organizations can tap into relevant company values, connections, and areas of expertise to build a supportive culture across the full organization. Toyetetsu believes in mendomi: treating workers like family. With this mission in mind, the company provides resources for all employees—which helps to ensure that fair-chance hires are not singled out—and promotes a culture of care and inclusion.

Some organizations have pursued fair-chance-hiring initiatives successfully for decades, learning through feedback to test new strategies, adapt, and to measure their results. This has helped them to meet workforce needs and have a meaningful social impact. Other organizations can do this too; for those that choose to pursue a fair-chance hiring program, the front-runners illustrated here offer lessons to follow. The next wave of fair-chance companies will help to build momentum, acceptance, and enthusiasm for a broad hiring approach that satisfies a variety of unmet needs.

The authors thank the following BCG and Cara Collective colleagues for their contributions to this article: Aine Keel, Alex Damiano, Ben Ruxin, Chenault Taylor, Hannah Paul, Hope Allen, Kate Myhre, Mariya Bokvun, Mark Toriski, and Rohan Angadi. In addition, Cara Plus wishes to thank the Stand Together Foundation and Walmart for the funding support that made Cara’s contributions possible.