This article was developed in collaboration with Cara Plus.

What’s the difference between a skills-based hire and a credentials-based hire? From a performance standpoint, not much: according to Harvard Business School research, job holders without degrees perform as well as those with degrees, but they stay in their jobs longer and are more engaged.

Skills-based hiring sidesteps evaluating job candidates based on traditional educational credentials—like advanced degrees, college degrees, or high school diplomas—in favor of focusing on candidates who have demonstrated mastery of the skills needed for the job, regardless of how they were obtained.

Many job postings include degrees as prerequisites, but how necessary are they? For example, 67% of job postings for production supervisors and executive administrative assistants require a college degree—but only 16% and 20%, respectively, of people in those roles have one. And, according to Pearson Business School research, only 13% of college graduates have the skills needed to start a job right away. This suggests education-based credentials aren’t always the best way to signal readiness for a role.

When companies strictly adhere to degree-based requirements, they exclude a significant portion of qualified talent: 50% of the adult workforce lacks a college degree. (See the sidebar “More Facts About the Workforce and Skills-Based Hiring.”) In 2023, 75% of employers in the US reported difficulty finding the skilled talent they need, a 17-year high.

More Facts About the Workforce and Skills-Based Hiring

...70 million adults in the US (including 55% of Latino adults, 61% of Black adults, and 66% of adults living in rural areas) don’t have a college degree but collectively make up half the workforce? This suggests that many jobs don’t really require a degree, even if a job ad calls for one.

…job seekers may soon be able to amplify their in-demand skills through learning and employment records, which serve as “digital résumés” that validate skills, education, and employment history? The National Governors’ Association Center for Best Practices and the nonprofit Jobs for the Future are working on this initiative.

...hiring based on skills is a strong bet? This is a message the American Psychological Association delivered decades ago and still stands behind. A hire that is based on skills, versus one that is based on education, is five times more likely to predict job performance. Skills-based hires get promoted at a rate comparable to that of traditional hires and are more loyal, with a 9% lengthier tenure at their organizations than their peers.

At the same time, the skills required for today’s jobs are evolving so rapidly that some jobs barely resemble the roles that existed just a few years ago, even if the job title and the person in the role remain unchanged. To help employees keep up with evolving requirements, organizations have had to diversify the pathways for skills acquisition to include work experience and employer-driven training in addition to traditional postsecondary education.

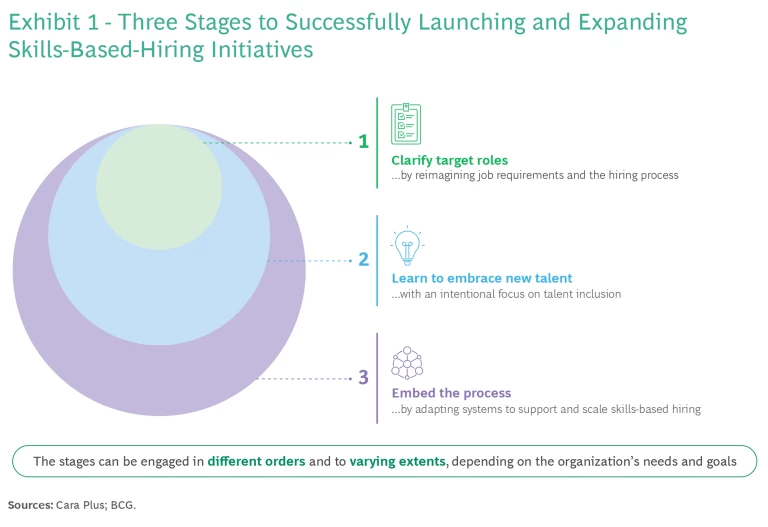

In 2023, BCG and Cara Plus (a division of the workforce development organization Cara Collective) collaborated to study employers of various sizes, across a range of industries and missions, to understand how they designed and executed skills-based hiring. While company journeys took different twists and turns, we found that most progressed through three broad stages. (See Exhibit 1.)

Here, we share examples of how these organizations succeeded with skills-based hiring at each stage. (For an at-a-glance look at how all three stages came together at one organization, see the sidebar “Skills-Based Hiring in Higher Ed.”)

Skills-Based Hiring in Higher Ed

Initially, when the university first sought to remove credential requirements, hiring managers—many of whom were struggling to fill critical roles—recognized the benefits of broadening the applicant pool but raised concerns about whether the higher-education institution was devaluing education in hiring. To overcome this challenge, senior leaders pushed one another to differentiate between mandatory and preferred qualifications for roles under consideration, ensuring that the preferred list was approachable to potential applicants. This exercise enlightened managers to the possibility of filling roles with qualified individuals who met the skill requirements, irrespective of their credentials.

Ultimately, the university successfully filled previously vacant managerial positions in the University of Chicago Press warehouse by eliminating educational requirements that were unnecessary for these frontline roles. The new emphasis on skills-based hiring helped the university strengthen its ability to recruit from its local community, where more than 30% of its current workers reside.

Clarify Target Roles

We found that organizations turned to skills-based hiring to solve for critical talent gaps: staff shortages, difficulty hiring or retaining talent, and workforce diversity. In most cases, they started small, addressing a specific need around a specific role. As they did this, they tried to take the long view to imagine how skills-based hires would progress in their careers and proactively build the systems to support them.

Identify roles that align with talent priorities. Examining data and reflecting on business and social imperatives can reveal where skills-based hiring could be a good fit. The organizations we studied sought out that evidence, which allowed them to concentrate on one or two roles, pilot skills-based-hiring programs, and focus on getting them right.

In 2019, BMO, a leading North American bank, created BMORE, an inclusive employment initiative that partners with workforce development organizations to source, hire, and retain untapped talent from local communities. When launching BMORE, senior leadership decided to focus on the associate banker role, an entry-level bank teller job needed in every BMO branch across the country.

An essential component of the program is hiring people for their transferable skills. The bank was confident that branch managers could teach the daily responsibilities of the associate banker role if new hires came in with a solid foundation of professional and interpersonal competencies, such as customer service experience and strong communication skills. They were right: since starting BMORE, the company has hired more than a hundred associate bankers and scaled the program to three states, with plans for further expansion.

Walmart has long recognized that skills-based hiring should not be limited to entry-level roles, having never required degrees for salaried store, club, and supply chain managers, who make $113,000 a year on average. It reimagined its career pathways starting in 2015, when it launched an initiative to help create a more dynamic, skills-based workforce system able to facilitate the development and advancement of hourly workers. Walmart made comprehensive changes to its hiring, training, compensation, and scheduling programs, as well as to its store structure. This included creating new development programs like the Walmart Academy training ecosystem and the Live Better U education benefit, both of which help employees build the skills they need to be ready for future jobs. The efforts continue to pay off: 75% of store, club, and supply chain managers began their careers as hourly associates.

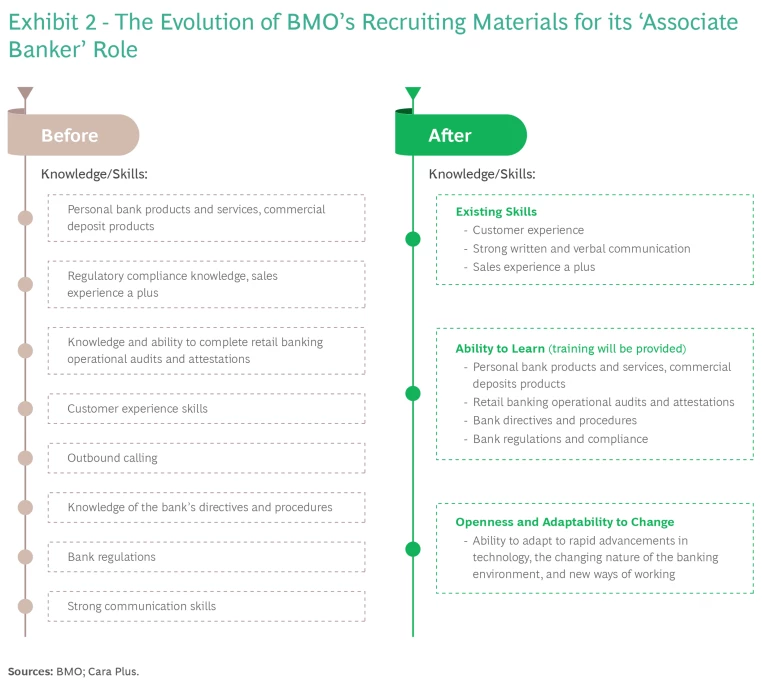

Catalog the skills that will replace the credentials. Once organizations identified the roles that could sustain nontraditional hires, they narrowed in on the component skills. Our research confirmed that a skills-cataloging exercise benefits both employees and employers. Listing specific requirements, along with transferable skills, made the role clearer to candidates and gave employers a better sense of what to look for in the job design and applicant-screening process.

BMO, for example, gained important insight into its associate banker job description while working with its community-based workforce development partner in Chicago. After reading the role’s qualifications and requirements, job seekers were asked whether they would apply. The bank was surprised to learn that no qualified candidates expressed enthusiasm—they didn’t see themselves in the role. With this feedback, BMO and its partner revised recruitment materials, prioritizing customer service experience, emphasizing that banking training would be provided, and clearly indicating which skills were required and which could be developed via training after hiring. (See Exhibit 2.) And it worked: at BMO’s first hiring event, 12 people were hired into the same role that had initially garnered no interest.

For Sam’s Club, Walmart’s membership-only retail warehouse clubs, removing degree requirements meant clearly defining alternative skills and competencies. Sam’s Club’s goal was to list specific and measurable abilities, such as operating equipment or using a designated software application, alongside broader competencies, like adaptability and teamwork. This differentiation was designed to allow hiring managers to make informed decisions regarding candidates’ qualifications.

Create career potential. In addition to ensuring that reimagined roles were accessible to a wider talent pool, employers connected those roles to longer-term career pathways. Doing so is especially valuable considering the loyalty and longevity of skills-based hires as a group. With this in mind, the employers we spoke with intentionally designed opportunities for new hires to benefit from skills development and mentorship and to gain a path to advancement.

BMO understood that job seekers would be more inclined to apply for the entry-level bank teller role if they knew it was just one step on the ladder of a banking career. So, BMO offered a two-part value proposition for potential associates: benefits from day one and ongoing professional development, a feature that was already embedded in BMO’s culture.

At their branches, employees received daily observation and feedback, monthly coaching sessions, and quarterly check-ins. At six months’ tenure, BMORE-sourced employees were also assigned a mentor from employee resource groups like the Black Professionals Network and the Latino Alliance. All of this was in service of supporting staff and enabling advancement into roles such as bank manager or market president—by providing them with the network and training to get ahead and build a long-term career path in banking and finance.

Walmart, too, invested in developing its frontline associate corps, tapping outside resources to provide academic and personal supports and upskilling opportunities. For example, the retailer established an education benefit that curates training programs to meet employers’ needs. Walmart associates received access to free education through Live Better U, which pays for associates to earn high school diplomas, skills certificates, and college degrees focused on specific skills. All were designed to enable career advancement in a way that felt accessible to individuals from a variety of socioeconomic and academic backgrounds.

Learn to Embrace New Talent

Organizations that commit to breaking the mold on hiring and development are often led by senior and frontline managers hired via “traditional” processes. They generally possess formal credentials—often in the form of degrees—and are accustomed to looking for candidates who do, too. The organizations we studied were no exception. To implement skills-based hiring, they encouraged leaders to move beyond their comfort zone and adopt new mindsets and practices.

Get senior leaders on board. In each case that we studied, skills-based hiring succeeded because senior leaders championed it. At BMO, lead product manager Loren Dinneen secured that senior buy-in for the BMORE inclusive hiring effort.

With a background in workforce development, Dinneen saw BMO’s chance to think differently about its social impact and leverage its leadership in the banking industry beyond philanthropic investment. Dinneen described his idea to senior leaders with just enough detail to pique their curiosity. Nothing was fully baked—on purpose. He aspired to create space so that others could weigh in with more perspectives. Instead of bringing PowerPoint slides to meetings, he mapped out his ideas “live” on paper, identifying the barriers to financial services careers along with some initial thoughts on how BMO could go about sourcing, hiring, and training job seekers from underinvested communities. It worked: he gained several early champions, highlighting the power of getting cross-sectional buy-in and the importance of bringing in the teams impacted as early as possible.

Get frontline managers on board. While getting senior buy-in was critical, it often wasn’t enough: cultural and mindset barriers were also an obstacle, unless those paradigms were flipped. In the organizations we researched, educating managers and implementing training programs to foster more inclusive environments overall were key.

For example, as Accenture embarked on building a skills-based apprenticeship program for its internal technology function, the professional services company put an emphasis on mobilizing its managers. Accenture knew it needed to appeal to both hearts and minds to gain their support:

- Changing hearts meant connecting people: having apprentices share their experiences with managers was a compelling way to demonstrate the value of skills-based hiring.

- Changing minds meant quantitatively showing managers the data: bringing factual evidence of the impact of skills-based hiring helped build the business case.

To further solidify manager engagement, Accenture developed a refreshed assessment process and specialized interview training for the individuals who would manage the company’s apprentices. This process engaged managers from the start. Rather than assigning apprentices to managers, Accenture allowed managers to have input into which individuals they would work with by participating in the full interview process. The training emphasized inclusive practices, too, such as reframing traditional introductions: instead of focusing on educational backgrounds (“Hi, I’m Rachel, and I went to this college and I completed this master’s program”), managers were guided to discuss work experiences (“Hi, I’m Rachel, and I work in operations and prior to this role I served as a financial analyst”).

Manager buy-in was important to BMO as well. At first, this felt like a tall order: most bank managers did not personally hire new BMORE employees and were skeptical that these hires could be as good as—if not better than—any other talent. Like Accenture, BMO turned to training. Through specially curated onboarding sessions, bank managers received guidance on how to best welcome BMORE colleagues into their branches and set the stage for what BMO was trying to achieve. The sessions proved crucial for BMORE’s success, because they focused on instilling confidence in the bank managers’ leadership, addressed their questions and concerns, and fostered support for a program that relied heavily on their participation.

Embed the Process

Adapting talent strategies to embrace skills-based hiring requires a variety of tactical changes that, in aggregate, felt daunting to many of the firms we researched. Nonetheless, the organizations recognized the effort it would take to be successful and made investments in community partnerships and technology to augment the work.

Establish partnerships to help source and develop talent. Partnerships can often fill a crucial role for the organization as it switches to a skills-based hiring model. Via partnerships, organizations can offer services outside their normal focus, get greater access to a new talent pool, and alleviate concerns about going into the new model alone.

Aon, a global professional services and management consulting firm, explored a new approach to talent development, having identified hard-to-fill, in-demand roles across several of its business units. Company leaders evaluated the four-year degree requirement for entry-level roles across career tracks, expanding the pool of talent eligible to apply and creating an apprenticeship model that enabled workers to gain on-the-job training, mentorship, and visibility into other opportunities within the organization. Apprentices are employees the day they start their apprenticeship with Aon and are working toward their associate degree while developing technical skills and building their network.

A key partner in this effort was City Colleges of Chicago, which codeveloped the training curriculum for apprentices pursuing their associate degrees, managed enrollments from start to finish, and coordinated schedules and tuition payments. Aon, for its part, stepped into the project manager role, ensuring that both parties met at least monthly to monitor apprentices’ progress at the local level and inform a broader set of corporate policies.

While the program took months to develop given the time to build relationships and deploy resources across both corporate and nonprofit settings, the end result was a great success. Since launching the initiative in 2017, Aon has placed more than 300 qualified early-career apprentices in a diverse set of full-time roles across IT, HR, sales, finance, legal, investments, and marketing.

Use technology to support hiring, evaluation, and advancement. Over the course of our research, we heard a universal concern about implementing skills-based hiring: ensuring that the process remained fair and consistent without the traditional benchmarks used to judge candidates in a credentials-based-hiring environment. To overcome this, organizations used technology-enabled solutions to address systemic biases and shift resources to provide more targeted support to employees.

The hiring process at Sam’s Club, including the recruitment of frontline hourly associates, begins with a thorough, objective evaluation of potential hires through a “member-obsessed” hiring initiative—an assessment that helps determine whether applicants exhibit behaviors or skills such as engagement and conflict management.

Walmart, widely seen as a leader in the tech space for skilling, used technology to combat career-advancement subjectivity by helping employees officially track their achievements, using verifiable skills badges that are relevant across multiple roles and can be leveraged throughout the employee journey. The company has invested in an internal academy model for retail advancement and made it a mission to manage records to ensure that skill badges are backed by real information.

And there is more potential on the horizon through new applications of AI. HR departments are already beginning to look to AI to help track employees’ skills and career paths, implement AI-enabled résumé review processes, and help the enterprise measure progress—with more to come.

Organizations need in-demand skills, and the best way to ensure they get those skills is to hire expressly for them without mandating particular educational credentials. Given that 70 million adults in the US don’t have a college degree, employers who dispense with degree requirements open their doors to a wider and more diverse pool of potential employees.

The authors thank the following BCG and Cara Collective colleagues for their contributions to this article: Aine Keel, Alex Damiano, Ben Ruxin, Chenault Taylor, Hannah Paul, Hope Allen, Jonathan Feldman, Kate Myhre, Mariya Bokvun, Mark Toriski, and Rohan Angadi. In addition, Cara Plus wishes to thank the Stand Together Foundation and Walmart for the funding support that made Cara’s contributions possible.