It can be a frustrating position for procurement leaders: they work hard to identify and unlock category savings every year, and a few may even have a strategy meant to map out the most cost-effective and efficient procurement plan for each spending category. But despite their planning, they often find themselves scrambling to plot out the necessary savings for the coming year or, worse yet, unable even to meet their quarterly targets.

When suppliers have stayed consistent, prices seem competitive, and internal stakeholders are not complaining about quality or service, the procurement team often operates as though its category strategy is good enough. But true category strategy excellence requires a refined multiyear plan built on a complete understanding of category needs, agility to adapt to marketplace and technology changes, and clearly defined actions to create category savings in the near and long term.

True category strategy excellence can help enhance innovativeness and flexibility across the organization.

An effective strategy delivers value well beyond the cost reductions it can provide. It also improves speed to market, decreases supplier and pricing risks, and helps enhance innovativeness and flexibility across the entire organization.

How Category Strategy Can Change the Game

Organizations have dozens of categories of direct and indirect goods and services across business units but often very little clarity about the effectiveness of the procurement strategy for each one of them and how they benefit the organization as a whole. To understand how well strategies are working now and what kind of improvements will be necessary, procurement should consider five questions:

- Is a category strategy with key actions actively in place?

- What time horizon does the strategy cover?

- What systems and tools will enable the execution of the strategy?

- Is the strategy aligned with the right segments of the organization?

- Are the benefits clearly articulated and big enough to make a difference across the organization, with multiple levers that will drive incremental value?

Teams may feel confident in their answer to the first question: they have developed a strategy that details the steps to be taken. But their answer to the second question may reveal that they’ve only plotted the steps for the next six months. And the third question could point out that they aren’t thinking about the right tools to add, such as a software solution to regularly source freight or manage temporary labor. Having a clear and positive answer to the fourth question would indicate that the process is cross-functional, meaning it’s well understood and signed off outside procurement.

The majority of category strategies fall short by not clearly linking strategy proposals to the benefits and value that they can bring.

Most important, the majority of category strategies fall short on the answer to the fifth question. By not clearly linking strategy proposals to the benefits and value that they can bring, internal business stakeholders will be less likely to agree to the efforts and uncertainty required to capture potential benefits. And it’s that focus on value that can be a true game changer. Whereas a traditional strategy—with annual category negotiations—may deliver a few percentage points in savings, a multiyear roadmap that includes a range of value levers can bring an organization double-digit savings and make a meaningful difference.

For example, one manufacturer felt stuck with a single supplier to provide land and ocean freight transportation to a key foreign market because the supplier’s shipping schedule and the company’s manufacturing schedule matched. Feeling pressure to save in this category, the procurement team reviewed the manufacturing schedule with the operations team and found it was possible to make adjustments and award a small percentage of volume to another freighter, creating competitive tension with their longtime supplier. In the end, a number of such moves delivered more than 10% savings in a category that had seemed hopelessly stuck. Also, the supplier’s commitment improved, and the changes launched a closer relationship with the operations team, unlocking the potential for new collaboration opportunities.

Eight Chapters in the Journey to Category Strategy Success

To develop a robust and practical category strategy, procurement teams need to take a fresh look at their organization’s existing categories and be ready to drive strategy to the next level. This involves eight actions:

1. Engage the most important stakeholders. Soliciting input is a key first step. Gather the relevant stakeholders for the category and discuss region-specific business unit requirements—such as cost-savings targets and risk tolerance—along with the impact the strategy could have on those requirements.

Unfortunately, this crucial chapter of the journey is not an easy one, as procurement managers well know. Stakeholders are not always eager to participate in the process, as they are unsure of the benefit their time and efforts might bring. At the end—once the results are in and the value is tangible—they’ll be glad to take part in the next round. Until then, procurement managers must bear the responsibility of making the case for change.

2. Understand the business requirements. It’s important to gain a complete understanding of needs, both current and in the future. This includes service level requirements, cost-saving targets, obstacles that could impede a category strategy, and tolerance for change, among other details. Sometimes this step includes rethinking what the business requirements have historically been.

For example, a large German utility provider wanted to improve its scaffolding category strategy. Scaffolding was a crucial component in repair and maintenance at its coal power plants. A large driver of costs had always been the requirement that the scaffolding be in place within four hours of the request call. In the past, plants had been operational around the clock, but procurement recognized that recent increases in the use of renewable energy meant that plants saw more downtime and no longer needed such a tight emergency response timeline, opening opportunities for new service levels and suppliers—and methods to create value.

3. Define a spending baseline and the evolution of that spending over time. Spell out the spending structure by segment, supplier, business unit, and region—and be as detailed as possible. Consider what spending patterns might be like over time. Assessing historic spending is not difficult and should be a part of every category strategy process. But gaining an understanding of what will drive future spending can be a game changer.

An aerospace and defense company wanted to understand what future spending would look like, not just for one year but across a three-year horizon. Members of the procurement team worked with their sales and project colleagues to build a forward-looking baseline, clarifying the product pipeline and building an understanding of demand patterns to come. This allowed them to shape bundles for suppliers and come up with the best possible plan.

4. Research the supply market. The basic steps of this phase include segmenting the supply market by region and product type, understanding the key drivers behind price development, and analyzing the relevant market economics, as well as suppliers’ cost structures. But it’s also important today to screen the markets for suppliers offering new technologies and standout innovations that bring real improvements to the business.

Leaders of one organization were eager to push forward greater sustainability efforts, which meant that improvements in category strategies should go beyond cost savings. In its strategy for consumer food packaging, for example, procurement wanted to find a way to cut back on single-use plastics and shift to greater use of fiber materials. This effort shook up the category and launched a worldwide search for suppliers with the most innovative offerings.

5. Analyze current suppliers. Conduct a complete overview of suppliers in use, including an understanding of where the business unit fits in to each supplier’s portfolio—and thus what sort of leverage for negotiation exists. Lay out any contractual obligations (duration, expiry, and time since last bid), the length of supplier relationships, an evaluation of supplier performance versus business needs, and the evolution of the supply base over time.

6. Perform internal and external benchmarking. Compare procurement practices—looking at costs, quality, operating processes, and other metrics—throughout the organization, across regions and business units. Then investigate how procurement is playing out among competitors. For example, one company may be outsourcing its janitorial work but is still paying for its own maintenance; if something minor malfunctions, the company takes care of the repair. But another might bundle a number of costs into one outsourced package—including janitorial, maintenance, and cafeteria operations.

7. Develop the category strategy. Synthesize the strategy, detailing three to six priorities for the next five years. Describe how it will maximize cost savings without unduly reducing other sources of value, ensure competitiveness, and mitigate short- and long-term risks.

Finally, procurement must obtain cross-functional agreement and signoff from business stakeholders and leadership. This step ensures organizational commitment to the savings, investments, innovation, and quality goals.

8. Plan implementation of the strategy. Successful implementation requires an understanding of the specific initiatives that will support the strategy and a clear quantification of the cost and noncost benefits that those initiatives will achieve. It must also include an activity plan that details who does what across the timeline of the strategy—from soliciting input from stakeholders to choosing negotiating approaches with suppliers—so that the team can oversee implementation and keep it on track.

Applying the Right Levers to Find the Most Value

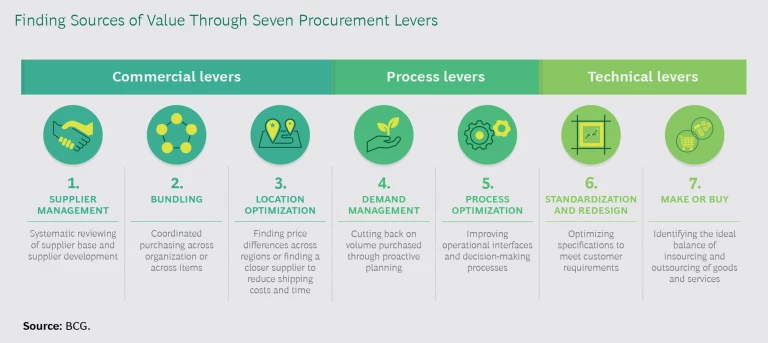

To source the most valuable suppliers and drive the best category strategy forward, procurement teams should consider seven key levers and address the ones that are applicable to each category. (See the exhibit.)

The first lever—digging in to the supply base—will be relevant no matter the category or type of business. Consider whether the relationship has been steady and reliable in terms of quality, cost, and delivery. And gauge the supply market overall, taking into consideration how competitive it is, whether it’s an oligopoly, if there are new entrants in the market, and whether there have been any mergers and acquisitions that could affect future prices or service.

The other levers depend on the category. Let’s say a team is creating a strategy for the purchasing of corrugated boxes. The first lever and the second—bundling—would be useful in making sure the business is using the best suppliers and getting the best prices. The third lever—location—might lead to a closer supplier, reducing shipping costs and time. The team could use lever five—process improvement—to make forecasting, delivery frequency, or inventory requirements more efficient. The sixth lever—optimizing specifications—would get the team thinking about the sizes and specs of the boxes, ensuring that they are not overengineered.

It’s easy to fall into a supplier relationship that feels comfortable because it’s what the business is used to and sometimes brings perks that the team counts on—tickets to sporting events, for example. And it’s common for procurement to rely on the same negotiating approaches with these suppliers. (See “Bringing a Category Strategy to Life with the AI Negotiation Coach.”) By being closed to new suppliers and approaches, companies limit their options—and not just on price. They may be missing out on greater quality, convenience, or innovation.

Bringing Category Strategy to Life with the AI Negotiation Coach

BCG’s interactive AI Negotiation Coach uses game theory and artificial intelligence to help buyers find the best negotiating lever for each situation, adapting approaches over time. We brought the coach to the procurement team of a Nordic food and beverage giant that had been tasked with doubling its savings performance over three years.

For the initial session, the coach asked the group 20 to 30 questions about each category, including corrugated packaging, logistics, ingredients, and facility management. For example:

- How many suppliers do you expect to provide a competitive bid?

- What is the price differential among suppliers?

- Which outcome is of higher importance: supplier relationship or cost savings and other goals?

The coach used the answers to build a decision tree that resulted in recommendations for the most powerful go-to-market approaches and supporting tools for each category.

The new negotiating levers led to vastly improved savings performance for the company—almost double from the year before. After that initial recommendation, the coach kept learning from buying experiences, gaining knowledge over time about what was working and what wasn’t. Using advanced algorithms, the coach could apply accumulated data to adjust the decision tree’s outcome and continue to improve recommendations.

The AI Negotiation Coach turns a staid process into an interactive, fun activity that delivers reliably large savings. Every member of procurement becomes an expert at using it. As the coach recommends new levers, the team can deploy them with confidence—knowing that the moves they make are backed up by data and experience.

The Benefits of Being Bold

One of the most important components of a strong category strategy—and the one most often missing—is the promise of an impressive savings target. The typical approach, when there’s one at all, is to remain conservative in making savings projections. But if procurement teams want business leaders to engage in the process and commit to some difficult work, they will have to sway them with big—yet realistic—expectations of dollar value, as well as promises of speed, quality, innovation, and risk mitigation.

In fact, communication with internal stakeholders is an integral piece of category strategy development. Many procurement teams today take on their strategy work independently and then expect business unit leaders to sign off on the plan. But by partnering with those leaders, procurement can have a better understanding of business requirements and how they will evolve. Engaging cross-functional stakeholders early in the process—and keeping the lines of communication open—can create an effective, realistic, and valuable strategy that often goes beyond purchase price. When the category strategy process is done right, it highlights the fact that procurement puts the business first, making it a highly valued office within the larger organization.

When the category strategy process is done right, it highlights the fact that procurement puts the business first, making it a highly valued office within the larger organization.

Delivering a Continually Renewing View of Value

The first attempt to create effective category strategies will seem like a lot of effort. As the procurement team completes more of these, develops its category strategy muscle, and raises the level of collaboration with stakeholders, the process will become easier.

Category strategy excellence is a powerful tool that should be at the core of the procurement team’s work.

Category strategy excellence is a powerful tool that should be at the core of the procurement team’s work. It maximizes value, efficiency, quality, and innovation, as well as mitigating risk—benefits that ripple across the entire organization and increase the visibility and stature of the procurement function. Bold leaders in procurement who set ambitious category targets will discover long-lasting benefits for the company and win respect for themselves.