In developing countries around the world, the demand for skilled and adaptive workers is growing. Rapid technological advances, as well as other forces, such as rising economic nationalism, threaten to disrupt the traditional development path from agriculture to manufacturing to a knowledge-based economy. As a result, developing countries must find a way to enhance their own innovation capabilities . If the workforce has insufficient soft skills and critical-thinking capabilities, however, that will be exceedingly tough to do.

Vietnam has made a bold move to address the challenge. In 2018, the Vietnam government, in partnership with the US government, created a new, independent, nonprofit university to bring the American tradition of liberal arts education to Vietnam. The new school, Fulbright University Vietnam, will graduate its first class in 2023.

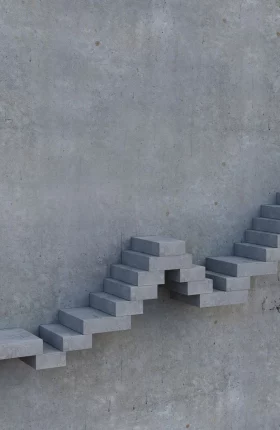

The American model of liberal arts education must be modified in light of the context of the country in which such a university will operate.

BCG’s work with the founding team to develop the value proposition and operating and financial models, and the subsequent preparation and codesign phases, revealed powerful insights. First, although the American style of liberal arts education is highly valued around the world, the model must be modified in light of the context of the country in which the new university will operate. Second, it is critical to attract the right group of students, faculty, and staff to create the culture required to make the university thrive. Third, students should be integrated into the design process to develop and refine an outstanding curriculum and overall university experience.

The culture the university has built in a short period of time has allowed it to respond and adapt to the disruption created by the COVID-19 outbreak , including by accelerating plans to offer online courses in partnership with universities around the world, such as Princeton University and American University of Central Asia. Other governments exploring the feasibility of building new universities from the ground up would do well to study and learn from the Fulbright model.

A Market Imbalance

Fulbright University Vietnam addresses a significant gap in Vietnam: large demand for top-tier higher education but limited supply, resulting in some 130,000 Vietnamese students enrolled abroad—a figure that has been growing at a clip of 15% per year.

The new institution offers an educational experience built on cross-disciplinary learning, problem-solving and collaboration, and adapts the liberal arts college model to the culture and reality of Vietnam. (See the sidebar “Creating the Harvard of Vietnam.”)

Creating the Harvard of Vietnam

Creating the Harvard of Vietnam

Building on the track record and success of FETP, the US and Vietnamese governments collaborated to develop Fulbright University Vietnam. The agreement included three critical elements: startup funding from the US government, land in Ho Chi Minh City from the Vietnamese government, and, most important, the promise of independent autonomy in governance and academic freedom.

Fulbright is absorbing and building upon FETP to establish Vietnam’s leading graduate school in public policy, as well as leveraging the FETP reputation to establish a flagship undergraduate program in the liberal arts and sciences.

Adapt the Liberal Arts Model to the Local Context

Although the founding Fulbright team knew that it wanted to create a vibrant liberal arts institution in Vietnam, just what such an institution should look like was far from clear. So, BCG conducted extensive research to understand the higher-education landscape, the possible positioning of Fulbright, and the views of such key stakeholders as Vietnamese students and parents and higher-education experts from around the world.

A Deep-Dive into the Market. We studied a variety of higher-education archetypes, including traditional US liberal arts colleges, such as Amherst and Wellesley; research-based universities, such as Dartmouth College and the University of Texas; smaller community colleges; and newer innovative schools, including Olin College of Engineering and Minerva Schools at KGI. We also held interviews with key leaders and stakeholders and conducted focus groups with students and employers in Vietnam. And we fielded a survey of 2,000 students and parents in roughly 40 cities and provinces.

A number of important findings emerged. We determined that the new university should offer an English-centric program with US accreditation and incorporate collaborative team-based work and small group discussions—pedagogical approaches nascent in Vietnam. We also identified exchange programs as a valuable offering because research showed that students and parents wanted their education to reach beyond Vietnam.

We determined that appropriate tuition levels would need to be financially sustainable for the school but also affordable for any qualified student in Vietnam. Ultimately, tuition was set at a rate that is higher than most other schools in Vietnam. But the university offers need-based financial aid—a first in the country.

The work also revealed a critical challenge: the liberal arts education label did not resonate in Vietnam as it did in other markets because parents and students worried that such an education would not position graduates well in the job market. As a result, Fulbright makes sure to address that concern through its messaging. The university remains firmly committed to the liberal arts approach but communicates how such an education—which develops critical-thinking skills through helping students learn to learn—is an asset in the job market.

Developing the Operating and Financial Models. We set out to design the program on the basis of the clearly defined value proposition. Classes in all years would be mostly small in size, and the later years would include independent research, co-ops, and internships. Those experiential components would be crucial because students would develop skills that are well suited to working in business and government in Vietnam and could start building local networks. This would be a unique differentiator for Fulbright when compared with universities abroad.

Though the right operating model was firmly established, the financial model needed to be more flexible. BCG assessed the potential cost structure of the university, including the amount of faculty and administrative staff required depending on different scenarios for student enrollment. We also explored a series of fundraising sources as varied as high net worth individuals, corporations, and public and nonprofit institutions, creating an initial engagement strategy for each. Then we used that insight to create three different scenarios for the initial takeoff of the university, spelling out the adjustments that Fulbright would need to make in each case. Ultimately, a combination of US and local government support, tuition revenue, and philanthropy provided the financial means to launch the university.

The operating and financial models created the vision and basic principles for the new university. Then it was up to the Fulbright team to implement the plan, making adjustments and changes according to the actual circumstances in Vietnam.

Students and Faculty Create the Culture

With the basic blueprint for the university established, the Fulbright team set out to recruit students and faculty who reflected—and would help foster—the right culture.

Fulbright students had to be willing to take a risk on an innovative and unique institution that didn’t yet exist.

The Fulbright student body needed to be a special group. The team was looking for students who were willing to take a risk on an innovative and unique institution that didn’t yet exist—and that had no current student body, faculty, or campus. The team also needed students who were eager to play a role in shaping Fulbright and willing to embrace an ownership role, rather than being essentially customers of the university.

The process of recruiting and selecting those young people started with an all-hands-on-deck campaign to win the hearts and minds of prospective students, their families, and the Vietnamese public. To do so, the Fulbright team needed to overcome three primary obstacles.

First, Fulbright was new and not well known, so the team traveled across the country to visit high schools and engaged print and digital media outlets for exposure.

Second, given the skepticism about the value of a liberal arts education in Vietnam, the team engaged reputable educators and journalists to earn their visible support (through social media and events), while at the same time hosting demonstration classes for students in key cities to allow them to get a sense of what the educational experience at Fulbright would be like.

Third, in a society where need-based financial aid is a new concept, the team sought to inform families across the socioeconomic spectrum of the opportunity and encouraged their children to apply.

Fulbright also attracted unique students through a highly differentiated admissions process. Instead of using Vietnam’s national standardized exam, Fulbright conducted a comprehensive admissions process that included personal essays, the submission of an original piece of work of any medium, and participation in a group interview day that simulated what it would be like for a student to attend and help build Fulbright University Vietnam. At the group interview day, students formed teams and pursued a project, for example constructing a series of paper airplanes that could fly further than those of other teams. The exercise, which required the teams to collaborate, test, and refine their products, helped identify students well suited to the agile culture that would define Fulbright and get those students excited about coming on board to shape the new university. Ultimately, among the hundreds of students who applied, 55 enrolled to form Fulbright’s first cohort of undergraduate students, called the Co-Design Year class because they would spend a year prototyping and building various aspects of the university with the faculty.

The faculty hiring process similarly aimed to attract instructors who were a match for the new university’s mission and culture. The Fulbright team had applicants conduct classes in front of groups of potential students, collecting feedback from those students on how compelling and engaging the instructors were. In addition to interviews with the Fulbright leadership, each faculty candidate also gave a talk outlining the impact they could have on, and the unique contribution they could bring to, the university. The Fulbright team was looking for creative and driven faculty who had a vision for the type of class and program they would create at the school and who would thrive with a high degree of autonomy and responsibility. Through the process, they found and hired 15 founding faculty members who would join the Co-Design Year students in building the university’s academic program.

In parallel with recruiting students and faculty, the Fulbright team began work on the design and construction of the new campus. With the goal of creating a modern, sustainable, and connected campus, Fulbright brought in a leading New York architecture firm, which specialized in designing world-class facilities for technology companies, to work in partnership with a local architectural firm that had a deep understanding of the local context.

Iterate and Refine Through Codesign

The new faculty and student body drove the next, and perhaps most critical, stage: prototyping and developing the university. That process borrowed from the creative approach taken by Olin, which recruited 30 students to spend six months testing and brainstorming the development of the new school’s curriculum and student life.

Fulbright embraced the approach and formally launched the Co-Design Year in fall 2018. Architects for the campus interviewed students and faculty to integrate their input into the design. Fulbright’s 55 students and 15 faculty members were sorted into teams to help shape everything from student life to the curriculum.

Some teams helped to develop the activities that were integrated into dorm life and established student clubs and organizations, such as the debate, film, and business clubs—15 of them in the first year alone.

Other teams tested and refined class offerings. That process was designed to answer two key questions:

- What elements of the traditional liberal arts style of education should be incorporated into Fulbright, and which elements should be changed to reflect the specifics of Vietnam?

- What features should be included in Fulbright’s model to make it relevant for the new century?

The development of Fulbright’s rhetoric class, based on liberal arts courses designed to help students learn to make logical and well-reasoned arguments, illustrates how the codesign process answered the first question. The original syllabus was heavily weighted toward the western tradition of direct, and at times vigorous, debate. Students formed a group to research and redesign the class to integrate a more eastern approach to the course, which focused more on building consensus and cooperation.

The second question is equally important. As technology continues to transform society, it will be critical for workers to have both the technical and interpersonal skills required to fully harness the potential of those tools. Students in the Co-Design Year participated in an engineering class that incorporated such thinking. During the course, students spoke with elderly citizens to understand their needs and challenges, and then developed products that would help address those issues. As a result, some promising new products were identified. But more important, the class helped students understand the power of collaboration and empathy.

In September 2019, 120 students from across Vietnam, including returning students from the Co-Design Year class, arrived on Fulbright’s campus for the official inaugural school year.

As has been the case with higher-education institutions around the world, Fulbright needed to respond quickly to the fast-moving COVID-19 pandemic. The university’s agile culture was a major advantage. Fulbright quickly switched to virtual learning while also accelerating the rollout of online courses in partnership with universities around the world, including Bard College, Dartmouth College, and Princeton University in the US and American University of Central Asia. Fulbright will rely on student input, much as it did during the codesign year, to refine its online-learning approach. And the school is developing new ways to run student recruitment and admissions activities online.

While these moves will be critical right now, many actions will likely remain part of the model even after the pandemic subsides.

Regardless of those adjustments, the key pillars of Fulbright’s success will remain firm: the power of a liberal arts education, the importance of building the right culture, and the need to draw faculty and students into the development process.