BCG helped Miami-Dade County Public Schools, Miami-Dade County, and other partners start Together for Children (TFC), a unique initiative that combines targeted data, programmatic orchestration, and community involvement to identify at-risk children and tackle the root causes of youth violence.

Any child lost to violence is one child too many. Jarred by the elementary school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, Miami-Dade County Public Schools’ Superintendent Alberto M. Carvalho and Miami Mayor Carlos A. Gimenez brought together more than 100 government and law enforcement agencies, local nonprofits, and business and education groups in January 2013 to improve the safety of schoolchildren.

Out of that initial effort was born a focused initiative—a pioneering new approach to combating youth violence and helping at-risk children perform better in school. The partnership—made up of BCG, Miami-Dade County Public Schools, Miami-Dade County, and other local organizations—developed a data-driven vision and cultivated community buy-in to launch TFC, an ambitious coalition for change. It’s an approach that could provide a blueprint for change for other cities.

Data & Analytics—and Beyond

To address Miami-Dade’s challenges with student violence, BCG and the local partners developed a customized approach drawing on best practices from a wide breadth of private and public sector experience. What is unique about the solution in Miami-Dade is the tailoring of analytics, program management, and change management to a situation involving such a diverse set of organizations—all rallying together to create a data-based program for good.

TFC builds on the innovations pioneered by Get IN Chicago, a youth-violence prevention fund that has also been supported by BCG. Get IN Chicago invests in proven programs and deploys analytics to help grantees and the larger youth-serving system focus interventions on those most acutely at risk for violence. This decidedly disruptive initiative with a highly targeted public-health approach allows limited resources to be prioritized in order to create impact on a communitywide and, more important, an individual level.

Like the Chicago program, Miami uses disparate data sets spliced together to identify children most in need of support. This idea is put into action by analyzing a variety of risk factors among schoolchildren—including test scores, attendance records, location, and math and reading proficiency—to identify the most at-risk neighborhoods, schools, and youth. (Get IN Chicago’s data analysis of a broader data set necessitated a larger focus on a different population—out-of-school youth and those involved in the justice system, among other risk factors. The more data that is shared and available, the more robust the answers from the analysis.)

One of the important differences between the programs is that TFC is focused on long-term sustainability while Get IN Chicago is operating on a five-year time horizon. With this in mind, and the population identified, TFC invested heavily in getting community buy-in and setting up infrastructure. Our perspective is that previous efforts—operated at the government level in Miami and elsewhere—may not have reached their full potential because those running the programs were too far removed to fully understand what was needed on the ground. TFC has created the groundwork for a sustainable two-tiered infrastructure by: 1) implementing a grassroots strategy that enlists neighborhood groups as the owners and drivers of the social service programs and targeted interventions; and 2) providing support to these neighborhood coalitions through a lean overarching structure that aligns and supports neighborhood efforts and resources and is moving toward tracking progress—similar to best-practice program management offices.

Although the program is still young, there are already impressive results and indicators. In 2017, juvenile arrests (including violent crime) were down 31% compared with 2013. And during the summer months specifically, which are typically the most risky, juvenile arrests were down almost 50% in 2018 versus 2014. Targeted programming in elementary and middle schools, tailored to reduce truancy, increase graduation rates, and help homeless children stay in school, has reached more than 10,000 high-risk students. While there are a number of contributing factors to changes taking place, TFC’s programmatic efforts are playing a big role that is only expected to expand.

Three Core Elements to Drive Impact

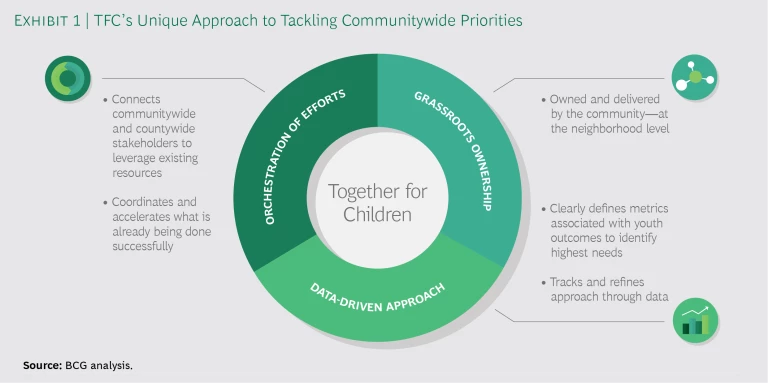

Three elements—data, community participation, and orchestrated oversight—make TFC unique and have propelled its success so far. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Data Focus. TFC’s foundation is a data-driven approach to changing the status quo. The coalition’s work was kicked off by combining various data sets to enable regression modeling that identified victim risk factors. Based on this analysis, the coalition was able to identify where to focus its efforts, serving students according to a better understanding of their needs. BCG initially sifted through data from about 185,000 youth, pinpointing the ultra-high-risk children, who made up 1.2% of the total and were clustered in 19 zip codes within Miami-Dade. (Similarly, in Chicago, the acutely high-risk population is estimated at 2,000 to 4,000 youth largely focused in seven neighborhoods.) Using this insight, blended with other efforts, TFC designed three referral programs to enable the targeting of services for students in elementary and middle school and their families and for youth who are coming out of the juvenile justice system. This initial model proved to be reasonably accurate, though a lack of resources placed limitations on the ability to keep the analysis up-to-date. Part of TFC’s longer-term goal is to build an expanded set of community-level data and analyze it as a means of improving service delivery for the most at-risk individuals. Through a small, dedicated data science team, the plan is to improve the data set so the analysis can become more predictive, identifying early-warning signals and enabling earlier interventions.

- Grassroots Community Ownerships. While the predictive modeling provides a tremendous start, local ownership and customization is an absolute requirement for successful interventions. TFC formed six neighborhood coalitions that have ownership of the services for their areas, letting communities develop action plans and services tailored to their specific needs. This outreach includes family engagement and leadership programs, truancy prevention programs, internships, communication training, and family counseling. BCG helped create an organizational framework for the neighborhood coalitions—including committees and governance rules—to ensure that their work is sustainable. This grassroots, empowering approach helped engage community leadership, clarified where to allocate resources, helped with data collection, and drove early fundraising efforts.

- Orchestration. After initially considering a typical nonprofit structure, BCG helped TFC move to a lean organizational setup that directs resources efficiently without adding significant overhead. At its core, TFC plays a role similar to a program management office, providing support and coordination across teams and neighborhoods, removing roadblocks, communicating key information across the organization, and helping stakeholders work together. Founding TFC members, an emerging advisory board made up of leaders from each of the six neighborhood coalitions, and an accountability director keep TFC independent, anchored in the community, and focused on agreed-upon goals. This structure will give TFC the ongoing ability to coordinate, support, and measure efforts—without eating up valuable resources. (See Exhibit 2.) Balancing these different elements is hard, but it’s a critical part of TFC’s success. It took years of work—including defining the vision, outlining specific initiatives for tackling youth safety and well-being, and establishing a structure for coordinating effects—to get the groundwork in place and ensure that the coalition could have a long-term impact.

Next Steps for TFC

Now, after five years of slow, steady, and not always linear progress, TFC is ready to scale up to become an independent, sustainable entity. This shift will make it possible for TFC to broaden its impact and help other cities nationwide replicate its model.

TFC as an independent entity recently received a first tranche of private funding, which will help solidify its impact in initial neighborhoods, invest in analytics to support risk identification and measurement, improve data integration capabilities, expand neighborhood and countywide action plans, and create programs for children in other age groups.

In the short term, this formalized structure will let TFC better support neighborhood coalitions as they implement action plans focused on youth safety. Over the longer term, the goal is for this orchestration of resources to improve youth and family outcomes more broadly through better family engagement, higher academic performance, decreased incidents of violence, and other improved social determinants. The plan is to take an agile approach to program execution based on learnings and outcomes along the way—working toward the best possible results within a complex, multistakeholder environment.

A Model Ready to Replicate?

Although no one has truly solved the problem of youth violence, Chicago and Miami are good examples of initiatives that are going down the right path with a focus on acutely high-risk youth, coordinated services, and community involvement. An early look at success metrics indicates that the TFC model is scalable and replicable in other major cities. It shows that change can happen through outstanding coordination and a relatively small amount of funding to drive impact on a large scale.

TFC exemplifies the importance of orchestrating resources effectively; monitoring, measuring, and improving data use; and getting local buy-in. This structure has been particularly powerful because it has allowed people from a wide variety of organizations to step in and take leading roles over time, including representatives from Miami-Dade County Public Schools, Miami-Dade County and the Juvenile Services Department, the Children’s Trust, United Way, the Melissa Institute, the Miami Foundation, the Jorge Perez Family Foundation, municipalities, and local service providers—as well as community leaders and stakeholders, who are key to driving collect impact.

The issues that TFC addresses are some of the most significant of our time—brought back into focus with incidents such as the recent Parkland shooting just north of Miami. The program’s unique approach can be followed anywhere with minimal investment—if the right stakeholders participate. It’s a model well worth watching.