Public sector actors—no less than private sector ones—now confront a world of unprecedented disruption. Environmental dangers, demographic and cultural shifts, rising expectations of efficiency in government, and, of course, rapid and ceaseless technological innovation continue to upend familiar paradigms. This makes transformation —that is, achieving a fundamental change in strategy, operating model, organization, people, and processes—as much an imperative for the public sector as for the private sector.

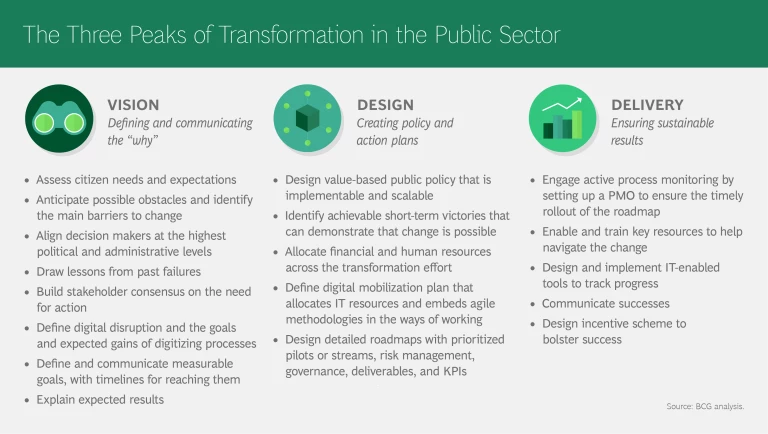

But public sector entities find transformation particularly daunting—especially when it comes to creating and communicating the case for change and ensuring sustainable delivery of results for stakeholders. BCG’s “three peaks” framework for transformation in the public sector guides organizations through every phase of the end-to-end transformation process.

Why Is Transformation in the Public Sector Imperative?

While the public and private sectors face some common challenges, many differences demand an approach to transformation geared specifically to enable the public sector to address:

Waning Trust. Even though global public opinion surveys reveal low levels of trust in business, discontent with the political status quo is creating genuine upheaval: Witness the backlash against liberal economic and immigration policies evident in the Brexit vote in the UK as well as in the recent elections in the US, France, Germany, Italy, and Austria. Even among more moderate voters, skepticism about the effectiveness of public policy and government’s ability to deliver on its promises runs high.

Rising Expectations. Yet the public’s skepticism about the efficacy of government action isn’t slowing its demand for more public solutions to critical problems. How should countries manage border protection and immigration policy in an era of mass migration? What should they be doing to mitigate climate change? How can they protect their citizens against terrorism? Provide public services to both depopulated rural areas and burgeoning megacities? How should they gear their economies to be globally competitive in the age of Industry 4.0 without leaving large segments of their workforces behind?

Budget Constraints. Even as expectations for government rise, many countries have reached the ceiling of tax rates the public is willing to accept. Virtually all countries are experiencing a demand for greater efficiency in the use of reduced public funds. And this is pushing some public services and entities to the very brink of operational failure.

Employee Frustration. Many civil servants have become frustrated and disillusioned after the failure of previous transformation efforts. To make performance improvements possible, they must be reengaged.

New Opportunities and Demands Unleashed by Digitalization. Through the ability, for example, to design value-based, data-driven public policies, create new delivery models based on citizens’ input, or streamline internal processes, digitalization offers enormous opportunities for the public sector to transform the way it serves the public. It can simultaneously boost the quality and lower the costs of services delivered to citizens.

Acute Challenges to Public Sector Transformation

In projects and discussions with dozens of politicians and civil servants in countries around the world, BCG has uncovered several acute challenges that public sector actors face in undertaking transformation. Most prominent among them: defining the “why” of their transformation efforts, and delivering concrete and effective results from these efforts in the form of improved services for all their citizens.

Because public sector entities find it challenging to define the why—that is, to create a vision for a transformation effort and what it should achieve—and bring about concrete results, they too often focus their attention on designing new policies and planning for their implementation.

The result is transformation efforts that fail because they lack buy-in from political and administrative leaders, employees, and citizens or because they fail to deliver on their promises. Such failures only fuel the skepticism about government that transformation is intended to overcome and make future successes more difficult to achieve.

Further challenges arise from the complexity and enormity of the transformations that pubic sectors must undertake. First, whereas all corporate transformations set profits as the same ultimate goal, the objectives of a public sector transformation can’t be broken down as simply. Second, cities, provinces, and nations must engage a high number of citizens. These populations are of course much larger than a group of factory or division—and even companywide—employees. Third, the public sector must engage in their transformation all their citizens—across geographic locations, cultural and sometimes language differences, and diverse desires and needs.

With these challenges in mind, and based on our experience with both private and public sector transformations, BCG has created a systematic approach to transformation in the public sector, refined with the input of government clients, to ensure attention to all components of an end-to-end transformation process.

BCG’s Three Peaks Framework for Public Sector Transformation

For public sector organizations to have a successful transformation journey they must climb three distinct “peaks”: vision, design, and delivery. Government officials and top civil servants need to invest sufficient time and energy in all three phases.These three peaks overlap and are intertwined over time; they are not linear. Rather, a successful transformation must be adaptive and iterative, with feedback loops and prioritized waves of initiatives that are regularly redefined. In short, work on the three peaks runs in tandem and overlaps throughout a transformation process.Peak 1: Vision—Defining and Communicating the “Why”

Defining the why of public sector transformation efforts can be tricky owing to two fundamental features of public sector organizations: they serve many masters who have many different goals.

That is, while for-profit companies may have multiple stakeholders, public sector actors have especially large and heterogeneous assortments of constituents. In public education, for example, stakeholders include students and families, teachers and teachers unions, school administrators, private suppliers, public and private funders, political parties, and local authorities.

Likewise, while private, for-profit organizations are typically oriented toward a single, ultimately monetary objective such as “sustainable value creation” or “cash,” the public sector must address multiple, sometimes conflicting, objectives that can be subject to rapid, politically driven change.

In the face of these challenges, establishing the vision for a public sector transformation requires a great deal more effort than for a private sector one.

Ensuring Legitimacy and Building the Case for Change

Employees need to be convinced at the outset both that the case for change is compelling and that the change effort enjoys support from the top levels of the organization. In the public sector, a transformation effort must have legitimacy with the public as well. Building both the internal and the external cases for change entails a number of steps:

- Assessing social needs and citizen expectations by drawing upon a full range of quantitative and qualitative sources—such as public data and reports, benchmarks, academic studies, press reports, feedback from both citizens and other ministries and/or levels of government. In its work with public sector clients, BCG also uses its proprietary MindDiscovery approach to move beyond traditional focus groups to capture customers’ needs, desires, and attitudes.

- Anticipating possible obstacles and identifying the main barriers to change

- Aligning decision makers at the highest political and administrative levels to gain visibility and help maintain commitment over the long term

- Drawing lessons from past failures of similar reforms and policies

- Building employee, citizen, and other stakeholder consensus on the need for action

- Defining both how digital disruption is affecting service delivery and the goals and expected gains of digitizing processes

Setting, Prioritizing, and Communicating Clear Objectives

With legitimacy established, public sector leaders need to address both their internal and their external constituencies by:

- Defining and communicating clear, ambitious but tangible, measurable goals, with timelines for reaching them

- Explaining expected results

Peak 2: Design—Creating Policy and Action Plans

In the next phase of a public sector transformation, organizational leadership must translate the vision into action.

Crafting Policies

In transforming the way government delivers services, public sector actors must focus on delivering value for citizens, a concept that involves both the quality of service and its cost. One example of value-based public-policy is value-based health care, which taps existing data on health-treatment outcomes to identify and disseminate evidence-based best practices proven to work. Such an approach unites all the stakeholders in medicine around a shared objective and transparent goals.

The same value-based lens for public policy could, for example, be used to measure and improve outcomes in education , public safety, and social policy, among many others.

Policies should also be designed for both short- and long-term impact. Short-term results are especially important for convincing both citizens and public employees that it is indeed possible to transform the way government provides public services.

And they must be designed from the start for both sustainability and scalability, keeping internal and external constraints clearly in mind.

Finally—and critically, given the special challenges the public sector faces—the policies must be designed to be implementable.

Allocating Resources

In this action-planning step, organizations also define the required resources, which include:

- Financial resources—budget, nature of financers, financing models and timetables

- Human resources—staff and teams, required seniority, governance, formal and informal collaborations

- Functional resources—information systems, communication, HR—are particularly solicited during transformations.

Creating Detailed Roadmaps

Plans must provide a level of detail proportionate to the time span they cover. More specificity is need for shorter projects because creating opportunities for short-term victories not only brings credibility, as noted above, but also creates momentum and is useful for designing the dedicated structures that will deliver the most lasting and dramatic changes.

Many public sector transformations in which BCG has participated demonstrate the usefulness of a “testing phase” before full deployment. Such a pilot phase focuses on selected beneficiaries, territories, or sets of services to help identify roadblocks from, for example, operational inconsistencies or unexpected side-effects.

As with the vision phase, the design phase need take only a few months.

Peak 3: Delivery—Ensuring Sustainable Results

A major element contributing to the success of transformation programs lies in this third phase: the implementation phase—where the policy takes shape in the field in a structured and sustainable way and change is achieved. BCG experience shows that in the private sector, the costs of supporting and implementing a transformation are estimated at 10% of the expected gains.

Essential tasks for delivering sustainable results include:

Active Process Monitoring

An entity should continuously monitor the launch and progress of the policy actions undertaken, in the field, with dedicated and experienced staff. Such a project management office (PMO), ensures avoids crises and bottlenecks and enables adjustments to initial plans as needed.

Such a PMO should be led by people with adequate levels of seniority, empowered by access to top management, and armed with the ability to make and push decisions and change existing rules and regulations. The team must take a "problem-solving" approach that manages risk rather than avoiding it at all costs. The PMO most foster trust throughout the organization and work closely with it to allocate resources in order solve problems—including unexpected ones.

Enabling/Training Key Resources

During this phase, training the people in the field—service providers as well service recipients—is necessary to help them navigate the change. The key is innovative approaches that stimulate beneficial behavior changes among the citizens, while maintaining their freedom of choice.

Designing and Implementing IT-enabled Tracking Tools

To evaluate the strategic and operational success of the policy requires implementing IT tools and systems for collecting data and tracking and analyzing outcomes.

Recognition and Rewards

Finally, departments or agencies should highlight and communicate success stories to recognize civil servants who have played key roles in achieving positive outcomes. Financial and symbolic rewards bolster success.

While the vision and design phases of a public sector transformation should take only a few months each, the delivery phase requires resources and support all along the mandate timeline—typically for a few years.

Climbing Onward and Upward

In a world of incessant disruption, the public sector must envision, design, and implement any transformation effort as part of a continual process of improving their service to citizens. This approach to and mindset of transformation will enable organizations to build new capabilities and continuously adapt to evolving contexts and priorities.