The turbulence of today’s business environment—volatility in market positions, unpredictability of competitive outcomes, and a widening gap in performance between winners and losers—makes classical strategic planning increasingly limiting. To keep pace with incessant change, companies need a more adaptive and dynamic approach to strategy. In “ Adaptive Advantage, ” we described an approach that involves iterative experimentation through a process comprising variation, selection, and amplification, with modulation at its center.

Companies adapt to rapid changes in competitive markets by introducing variation into their products and internal routines. They select the most promising variations through stage gates, portfolio management, pilots, or full-scale tests. And they amplify and embed their successes through resource allocation, internal or external competition, and specialization. These activities are fine-tuned through modulation—the locus of strategic intent in the process—in response to the environment, corporate goals, and outcomes.

The choices a company makes in modulating variation, selection, and amplification are at the heart of adaptive strategy and its organizational implications. They affect organizational structure, governance, external relations, innovation, marketing strategy, and culture, to name but a few elements. The mechanisms of modulation are fundamentally organizational in nature: they are embodied in the way people make decisions and behave in the workplace. There is no adaptive strategy without an adaptive organization. Hence the critical importance of people advantage.

Challenges to Building Adaptive Capabilities

Large organizations need to be especially aware of the challenges they are likely to encounter in developing adaptive capabilities. Classical approaches to managing scale—delegation and specialization—can be highly efficient under stable conditions, but the hierarchical structures they produce are too rigid for the rapid learning and change required in turbulent environments.

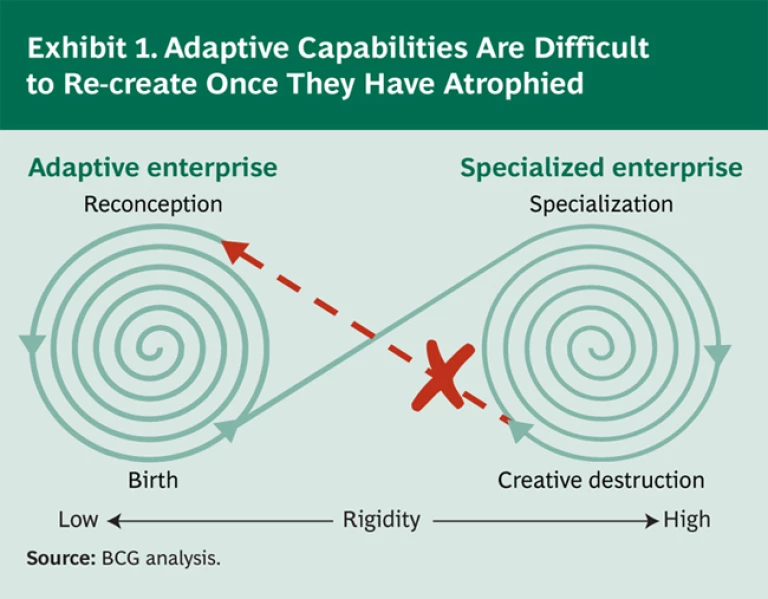

A narrow focus on leanness, too, can impede adaptability. Under pressure from competition and capital markets, some large companies have squeezed out not only inefficiency but also the diversity and variation needed to adapt to rapid change. What’s more, once adaptive capabilities in highly structured and specialized organizations have atrophied, they can be challenging to re-create. (See Exhibit 1.)

In addition, the cultures of large organizations—often internally oriented and with an intolerance of failure, an obsession with efficiency, and a bias toward consensus and obedience—can be ill suited to adaptability. And their management paradigms die hard, especially when they have been the basis for historical success, are integrated into training programs, and offer the comforting illusion that a company can perfectly foresee and control its destiny.

Characteristics of an Adaptive Organization

Nevertheless, some companies—even large, established ones—have discovered a way to overcome the barriers to adaptability. These organizations display five key attributes:

- Modular organizational units provide flexibility in a changing environment. Standardized (plug-and-play) interfaces enable the organization to recombine parts and rapidly introduce variations in products and processes at low cost and risk, as well as rapid shifts in resource allocation.

- The free flow of knowledge and power enabled by decentralized decision-making allows operations to detect and respond quickly to changes. This attribute is often reinforced by weak or competing power structures and a culture of constructive conflict and dissenting opinions.

- A limited number of guiding principles replace detailed standard operating procedures, which are impractical for managing unpredictable change. Adaptive organizations favor simple universal principles over strict rules for determining how individuals and teams should interact and how decisions should be made.

- Adaptive values encourage the organization to pursue economics favorable to experimentation rather than focus on avoiding failure, which is seen as a necessary part of experimentation. Adaptive values also promote productive dissidence, cognitive diversity, and an external orientation in order to allow a faster and more accurate response to a changing environment. And because adaptive organizations rely on individual creativity and initiative, they articulate a credible common purpose that transcends financial goals and mobilizes employees.

- Leadership through context setting acknowledges that in adaptive organizations, strategies are emergent rather than dictated. Therefore, leadership’s role is to shape the context for decision making rather than to specify and oversee the execution of an instruction set. The emphasis shifts from command and control to contextualize and catalyze.

Netflix, a U.S. video-rental company, embodies many of these characteristics. It is unique in the way it has codified a very explicit set of adaptive management beliefs and principles. Here are two examples from its “Reference Guide to Our Freedom and Responsibility Culture”:

- Process-driven companies are “unable to adapt quickly, because the employees are extremely good at following the existing processes. . . . We try to get rid of rules when we can.”

- “The best managers figure out how to get great outcomes by setting the appropriate context, rather than by trying to control their people.”

Even large industrial players can become more adaptive, as Cisco Systems demonstrates. Early on, Cisco relied on a hierarchical customer-centric organizational model to become a leader in the market for network switches and routers. However, as the company’s core market matured, CEO John Chambers created a novel management structure of cross-functional councils and boards to facilitate a move into 30 adjacent and diverse markets (ranging from health care to sports), as well as into developing countries. Cisco transformed itself from a company in which a few people made all the decisions to one with a decentralized, externally focused council structure. Employees are allowed to form boards even without a formal leader, thereby increasing agility and exploration. The company built a culture that is more amenable to risk taking and more accepting of failure. As a result, it successfully met Chambers’s aggressive target of generating 25 percent of revenues from new markets by 2010.

Getting Started

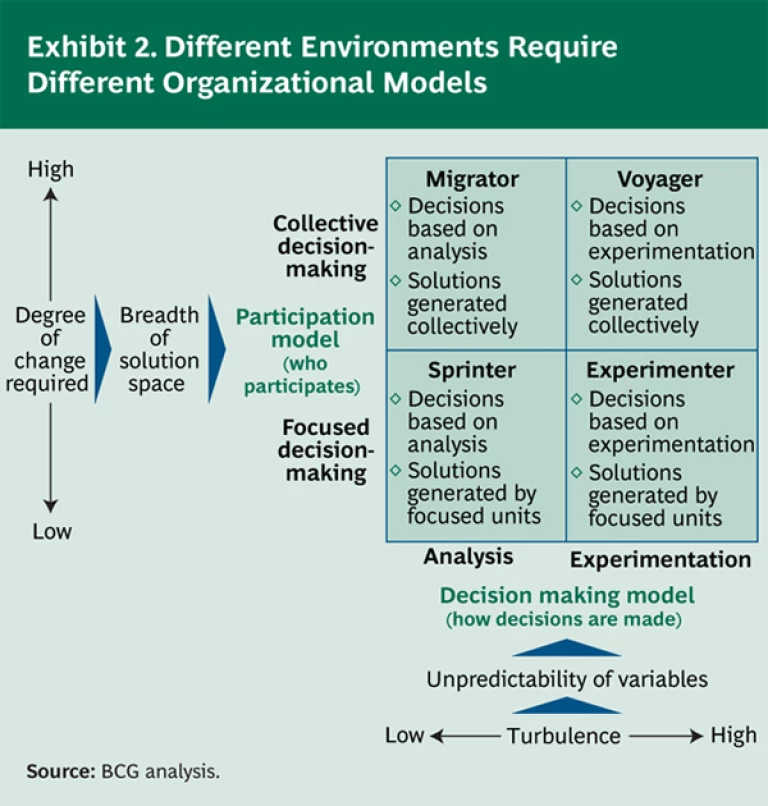

We believe that an increasing number of companies will find themselves requiring adaptive strategies and organizations. But how they achieve them will depend upon the nature of their business environment. In “ Adaptive Advantage ,” we explained that the appropriate adaptive strategy is determined by two characteristics of the business environment: the degree of turbulence and the degree of required change.

- The degree of turbulence—the volatility of market position and the degree of unpredictability in the business environment—determines how an adaptive company makes decisions. Relationships among key variables are more stable and predictable in environments with low turbulence, but they become unpredictable and difficult to analyze under conditions of high turbulence. Therefore, when turbulence is low, an organization can solve problems through analytic approaches and explicit decision-making, but it should rely more on experimentation and implicit decision-making when turbulence is high.

- The degree of required change—in terms of business model, capabilities or knowledge set, and number of affected areas in the company—determines the breadth of the solution space and the participation model of the adaptive enterprise. A broader solution space demands greater cognitive diversity and hence broader organizational participation. If a high degree of change is required, companies need to use collective decision-making to access a greater diversity of knowledge and opinion. If less is required, they can explore a narrower set of solutions and rely on a smaller, more focused group of specialists, experts, or leaders.

In that earlier Perspective, we also introduced four styles of adaptive strategy—sprinter, experimenter, migrator, and voyager. Each has its own organizational approach and is appropriate to different combinations of turbulence and required change. (See Exhibit 2.)

- Sprinter organizations operate in markets of low turbulence that require little change. They generate solutions in localized, discrete units; make explicit decisions based on analysis; and exhibit more specialization and centralization than the other adaptive styles. Still, they are adaptive: they rapidly and dynamically reoptimize their routines to the changing environment.

- Experimenter organizations use continual empirical testing to make decisions in a turbulent environment, but because the degree of change required is low, they can allow discrete parts of the organization to generate solutions. Therefore, the parts of the company that face uncertainty must empower the frontline to make choices and act, while other parts can behave like sprinters.

- Migrator organizations face environments that require significant change, so they generate solutions through broad-based collective participation. However, because turbulence is low, decisions can be based on analysis and deliberation. A migrator’s modulating unit is often a cross-functional group that collates inputs from multiple sources and makes deliberate, analytical decisions.

- Voyager organizations navigate environments of high turbulence in which a high degree of change is also required. Since no central authority can “know” the correct path, these companies rely on collective decision-making. They also make decisions empirically, since it is not feasible to analyze their way to a solution. And since problem solving at voyager organizations is collective, the periphery is empowered to detect and act on weak signals within an overall context set by management.

Traditionally, strategists have regarded organization and strategy as quite distinct, or they have viewed organization as merely a consequence of strategy. We have seen, however, that achieving adaptive advantage critically depends on having the right organization in place to solve the challenges posed by a dynamic environment. Strategy has therefore become intimately connected with organization, and the companies that succeed will be those that understand and seize a people advantage.