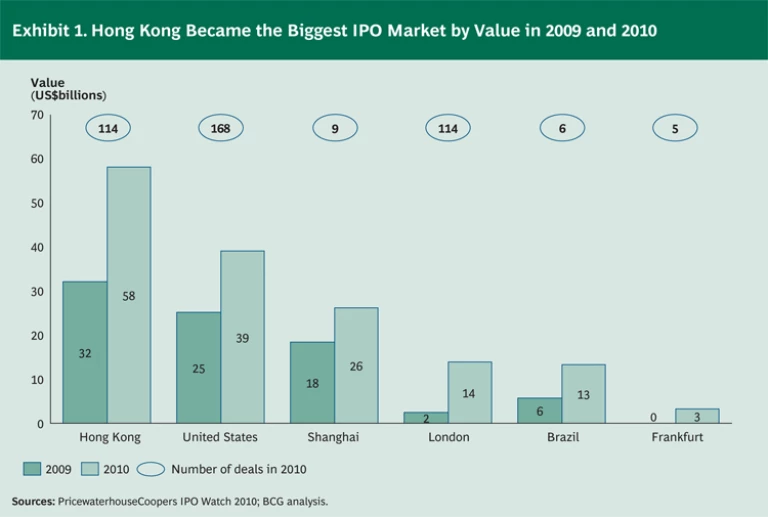

Hong Kong became the world’s largest IPO market by value in 2009 with public offerings that raised US$32 billion, and it held its lead in 2010 with offerings worth US$58 billion. (See Exhibit 1.)

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx) has been targeting foreign companies for IPOs and secondary listings since 2007, easing its secondary listing requirements in 2009 to attract some high-profile companies.

Related Article

No Time Like the Present to Plan an IPO

Businesses planning an IPO should begin extensive preparations now to be ready when markets recover, according to BCG’s analysis of European IPOs.

Foreign companies can list on the Hong Kong exchange in one of two ways:

- An IPO to Raise Fresh Capital. This approach requires full observance of the HKEx listing and compliance rules. Glencore’s London IPO, which occurred in May 2011, was accompanied by a Hong Kong IPO designed to raise 20 percent of its US$10 billion target. In June 2011, Samsonite, the luggage manufacturer, raised US$1.25 billion in an IPO in Hong Kong only, while Prada, the Italian fashion house, similarly raised US$2.1 billion in the same month.

- A Secondary Listing (Also Known as a Cross-Listing) That Raises No Fresh Capital. The introduction of existing shares to the HKEx avoids the need for public float procedures and imposes less onerous reporting obligations. Prudential, the U.K. insurance group, launched a secondary listing in Hong Kong in May 2010, followed by Brazilian mining giant Vale in December 2010 and Kazakhmys, the Kazakh copper miner, in July 2011.

The attractions of Hong Kong include access to investors in mainland China and other Asian countries; capital markets in this region have been more buoyant since the economic crisis than those in the West. Companies listing in Asia hope that the broader investor base increases liquidity and improves access to capital and that listing in a fast-growing market will raise credibility among investors generally and lead to a higher valuation.

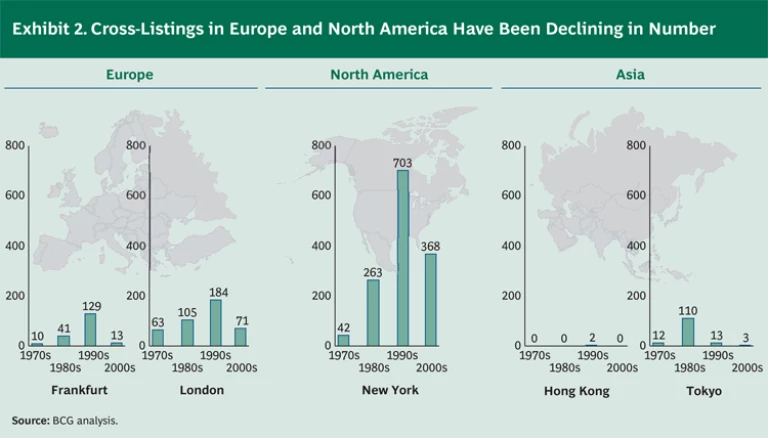

Cross-listings have been used to achieve similar objectives for decades. New York, London, and Frankfurt were popular choices for secondary listings in the 1990s, and there was a short-lived surge in Tokyo during Japan’s economic boom in the 1980s. However, many companies delisted in New York recently after finding that the costs and increasing regulation involved in secondary listings there did not produce the expected benefits. The number of secondary listings in Europe declined for similar reasons after the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000. (See Exhibit 2.)

Do Cross-Listings Improve Liquidity?

Studies of cross-listings by European companies on other European stock exchanges or in the U.S. have found that they initially increased trading activity, enhanced liquidity, and led to tighter bid-ask spreads. In most cases, however, these gains quickly melted away when trading in the stocks flowed back to the exchanges in their home countries.

Typical of these diminishing returns was the experience of DaimlerChrysler, which started to cross-list on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in 1998. Daimler delisted from the NYSE in July 2010, having found that international investors primarily traded its shares in Germany and through electronic trading platforms. Deutsche Telekom, insurance giant Allianz, power group E.ON, and pharmaceutical group Bayer have all made similar decisions, citing diminishing liquidity and cost as the main factors.

By contrast, SAP is an example of an export-led, high-tech company that has maintained its NYSE listing. The German software group, a market leader in the U.S., has repeatedly said it has no intention of delisting in New York.

Companies that recently listed in Hong Kong have yet to experience increased liquidity. A mere 0.2 percent of Prudential’s shares are traded on the HKEx, while less than 0.1 percent of global trading in Vale shares has been transacted in Hong Kong.

Do Cross-Listings Expand the Investor Base?

A 2006 study of Canadian companies cross-listed in the U.S. found that the practice led to increased investor recognition and raised the percentage of these companies’ equity held by U.S. investors. Those companies that achieved this wider investor base enjoyed a permanent increase in their valuations.

However, today’s information systems allow institutional investors to collect extensive information on foreign companies at the click of a button. In addition, trading is now largely conducted via electronic platforms that allow for easy and cost-efficient transactions across markets, reducing the need for companies to list on an exchange close to investors in order to attract them. The experience of German companies such as Allianz, Bayer, and SAP was that while cross-listing on the NYSE initially attracted new U.S. shareholders, large U.S. investors primarily hold and trade the shares of all three companies on Xetra, Deutsche Börse’s electronic trading platform.

Do Cross-Listings Improve Company Credibility or Company Valuations?

Empirical studies have found mixed evidence on the impact of cross-listings on company valuations.

On this basis, there may be some premium for companies from less well regulated markets listing in New York, London, and Frankfurt—or even in Hong Kong, which is regarded as a well-regulated market. But there are unlikely to be similar benefits for companies already listed in a well-regulated market. And a cross-listing in a less prestigious market might destroy value.

Among foreign companies that recently cross-listed in Hong Kong, their shares experienced no discernible boost following the announcement that they were listing there. Indeed, the abnormal returns were negative on the day of the announcement of secondary listings for Vale, Prudential, and Kazakhmys.

The attractions of Hong Kong have also weakened recently. The region’s equity market underperformed its peers in the first half of 2011, amid concerns over the quality of accounting and auditing standards among mainland Chinese companies. In June 2011, the HKEx saw its first IPO cancellation, and another five were called off before the end of the month.

Overall, Very Limited Benefits—If Any

The experience of IPOs and secondary listings in Hong Kong suggests that they are unlikely to be reasonable options unless the company is based in a poorly regulated market. Cross-listings do not significantly improve liquidity in the longer term, and large institutional investors increasingly use online trading platforms that obviate the need to expand the investor base by cross-listing. Meanwhile, hopes of higher valuations have ebbed—for the time being, at least—as Asian stock markets have lost momentum in 2011.

There is some evidence that companies from less well regulated markets that list on exchanges with high regulatory standards may improve their valuations. However, this is unlikely to apply to cross-listings in Asia by companies listed on markets covered by the three large European stock-exchange groups.