Little more than a generation has passed since the Chinese Communist Party charted a reform course for moving from a planned, largely agrarian economy to a more market-oriented economy. In that short period, mainland China has become the world’s second-largest market, and the country’s huge supply of relatively low-cost workers has allowed China to become a manufacturing powerhouse serving the entire world.

With incomes rising steadily, China’s middle and emerging-middle classes have grown at astonishing rates, fueling demand for previously unattainable goods and services. Local companies and multinationals are betting that they can find new sources of growth in China.

But economic growth and the eager new players have run up against a substantial challenge in China: talent is increasingly difficult to find and keep, and this talent shortage will only worsen over the next decade. By talent, we mean the set of employees, usually highly skilled, who help give a company its competitive advantage. The talent shortage applies across all ranks of the organization, although the challenge takes a slightly different shape in each group.

China’s talent situation is just as pressing for homegrown companies as for multinationals. Global challengers such as Huawei Technologies, Mindray, and Chint are finding that they must be increasingly aggressive in their recruitment of Chinese talent, especially the recruitment of managers who are familiar with both the local and the global context.

No wonder, then, that The Boston Consulting Group’s recent survey of HR professionals found talent management cited as the highest-priority issue in China. Companies that compete in China will need to raise their investment in talent management and to treat human capital with the same rigor as a capital asset investment. They will have to professionalize every stage of their approach—from recruiting and training to engagement and development.

What Employers Need to Know About in China

Scarcity of talent is a problem that pervades many emerging markets. But every country’s distinctive characteristics make it essential that companies acquire a deep understanding of the individual country’s local business context, right down to the provincial or city level.

To that end, it’s worth identifying the key factors that are shaping China’s talent landscape.

Demographics will not help employers. China’s median age is projected to rise from 34 in 2010 to 37 in 2020, a situation that has been fueled by the government’s policy of one child per couple. The size of China’s available working-age population will peak in 2015. By contrast, in other BRIC countries, such as India and Brazil, the working-age population will continue to grow over the next decade.

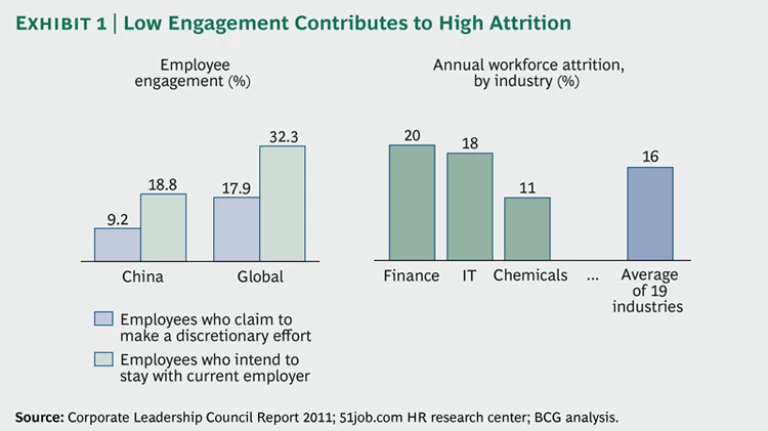

Employee engagement is weak, contributing to high turnover. Various studies of employee engagement in recent years—typically, measuring self-reported discretionary efforts and intent to stay with an employer—find the level of engagement among Chinese employees to be roughly half the global average.

Wages will continue to rise faster than productivity. Competition for talent has driven up wages: disposable income in China rose at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10 percent during the first decade of this century, while productivity rose approximately 9.5 percent per year. Over the next decade, disposable income is projected to continue to grow at a CAGR of 9.7 percent, but productivity is forecast to decrease to 6.9 percent.

Education is not aligned well with the skills that employers seek. China ranks very low in the alignment of its higher-education curriculum with employers’ needs.

Although government policies will help, they may not be able to bridge the entire gap. The National Talent Development Plan 2010–2020 aims to increase the share of highly skilled employees from 24 percent of the labor force to 28 percent by 2020, at the same time, doubling the share of college graduates in the labor force to 20 percent. The government is also trying to attract overseas talent, including students who, after pursuing higher education abroad, are returning to China. This group is relatively small, however, and the effects of government policies will take years to ripple through the economy.

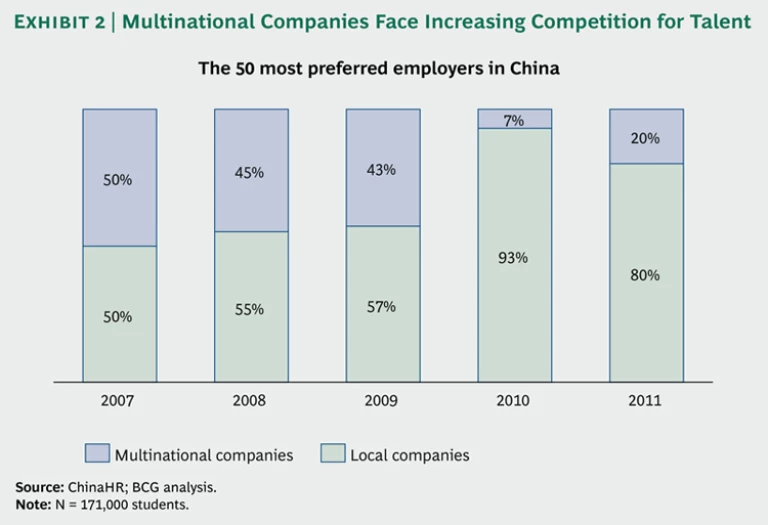

Multinationals face stiff competition from local companies. Multinationals are losing ground to local companies: 80 percent of the 50 most preferred employers in 2011 are Chinese companies, up from just 50 percent in 2007.

The convergence of these factors means that companies must get serious about talent management in China. China has plenty of excellent employees, but companies need to know where to look for them and how to develop them. Relying on serendipity to meet current and future talent needs is far too risky a plan. Instead, companies will have to professionalize their talent management. The following four imperatives of professionalization will raise the odds of success:

- Undertake rigorous planning of talent supply and demand.

- Craft and articulate a powerful employee value proposition.

Undertake Rigorous Planning of Talent Supply and Demand

The important first step is to systematically assess the company’s risk of shortfalls—and in some cases, surpluses—in workforce capacity for China. With the results of that assessment, the company can put a strategic plan in place to manage the risk and make talent investment decisions.

A supply analysis can be used to identify which job categories and functions face the most critical gaps that occur because of attrition, inadequate recruiting numbers, and other factors. Workforce demand, including an understanding of which capabilities and skills will be needed, can be determined through an evaluation of business and productivity trends combined with the company’s overarching business strategy for China.

This rigorous planning is particularly important in China, because turnover exceeding 20 percent in the context of 10 to 20 percent growth implies an annual renewal of 30 to 40 percent of an enterprise’s HR base. In addition to filling employment gaps, companies will also need to plan how they will develop and secure the scarce, largely unavailable skills and capabilities they will need.

Our research shows that, on average, the greatest supply-to-demand gap that employers in China will face will be for middle managers: at middle-management levels, there are high attrition rates, and personnel at these levels have relatively low mobility. Middle managers translate strategy into business plans, communicate with employees, manage the business, identify high-potential employees, and turn the employer’s brand promise into workplace reality. One multinational in China discovered that to meet its five-year growth plan, it would have to recruit, train, and develop 2,000 middle managers—the equivalent of one-third of its entire local workforce.

When a company is planning operations in different parts of China, its analysis should include a regional view. In the automotive industry, for instance, recent BCG analysis found larger talent gaps among engineering employees in tier 2 cities than in tier 1 cities. Still, an auto company might decide to locate engineering in a smaller city as long as it made a commitment to developing engineering talent internally.

By combining supply-and-demand calculations, the capacity risk and its immediacy can be determined by job family over the succeeding five to ten years. The gaps can then be addressed through a variety of measures, including targeted recruiting, retention programs for critical job functions, cross-training programs within job families, and leadership development programs.

In one such strategic-workforce-planning endeavor, Pfizer, a leading pharmaceutical company, set up its aggressive growth plan for China through 2020. Pfizer realized that it would need to fill sales management positions and to develop stronger capabilities in areas such as marketing at the provincial level. The company conducted workshops at the grass-roots level to identify key job families and competencies that would be most critical to the business’s success in China. It defined high-priority initiatives that addressed the identified risks by, for example, designing new career paths that would help employees cross business units. Pfizer China also defined a culture—people oriented, accountable, collaborative, and entrepreneurial, or PACE—which would permeate training and workshops through shared success stories.

Craft and Articulate a Powerful Employee Value Proposition

Given that competition for talent is fierce across the board, multinationals must raise the value of their brands in the talent marketplace by actively marketing the value proposition to employees and adding emotional dimensions to the recognized attributes of employment. The value proposition should be communicated regularly and consistently to solidify the message.

BASF, a global chemical company, crafted a targeted employee value proposition aligned with the company’s growth strategy. BASF, which had ambitious expansion goals in Asia and China, worried that its traditional approach—selling employment on the basis of the company’s long history and prestige—wasn’t sufficient in the increasingly competitive talent market. BASF decided to define an employee value proposition that would have resonance specifically in China.

Focus groups comprising a range of talent segments—from fresh university graduates to midlevel professionals—revealed the specific criteria people were looking for in an employer:

- The company should be ranked at the top of its industry. This criterion reflects the importance that the Chinese attribute to academic ranking as a way to move up the socioeconomic ladder.

- The company should offer career development opportunities that would give individuals exposure to new challenges and enhance their skills.

- A caring company should invite connection, a criterion motivated by a strong desire for affiliation with a chosen group.

On the basis of these insights, BASF determined which of the company’s existing characteristics could support each criterion and which should be strengthened. For example, BASF already had development programs for the top quintile of talent in China, so it designed more structured programs for the rest of its employees. One result of its various changes was that BASF doubled the number of students who went into management training.

To reach target segments, companies will need to use a variety of channels, including videos, links to virtual communities such as Renren, and in-person ties to local communities and universities. Procter & Gamble, for instance, maintains strong connections with 11 universities through local P&G “clubs” that offer training, lectures, and competitions designed to increase its exposure to this target segment.

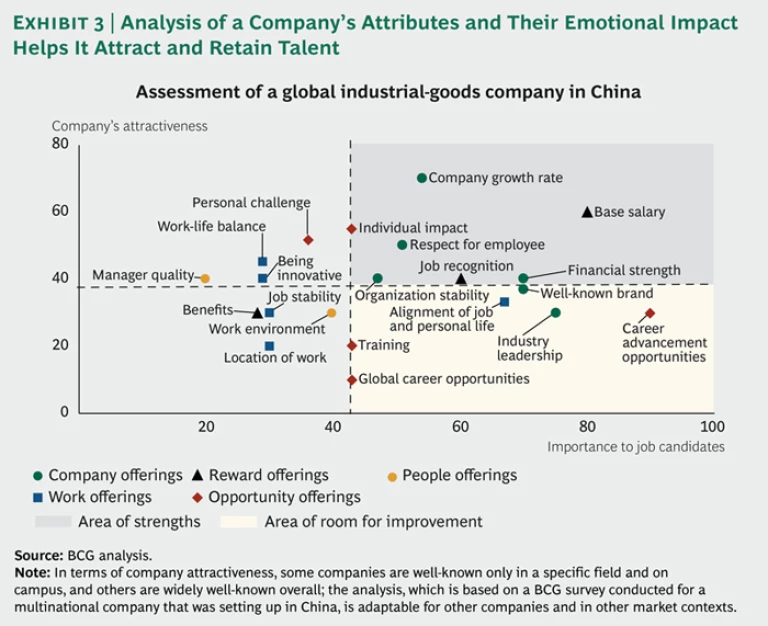

Because multinationals may be unaware of how they are perceived by Chinese employees and potential recruits, it pays to start with an outside-in survey that explores current and desired attributes of the company. Arraying the attributes on a matrix of attractiveness versus importance identifies the most important strong and weak attributes. These attributes can be further classified by their nature as company, reward, people, work, or opportunity offerings. (See Exhibit 3.)

Build a Talent Management Engine

Absent powerful ways of tuning in to what matters to employees, companies will be unable to deliver on their brand promise to them. Among the top reasons Chinese employees give for attrition is the employer’s scant attention to their career development. This shortfall generally is more pronounced among Chinese companies, as many multinationals do have more structured development programs. But multinationals tend to export their programs from the home country to China: they should tailor them for China. It is important to have a structured talent-management engine that reflects Chinese talents.

Recruiting, developing, and motivating talent takes time and money, and, for certain positions, the bill can easily reach a full year’s salary. Hence, it’s essential to build formal processes for career reviews, performance evaluation, and compensation management and training. A strong partnership with the line businesses will ensure that the talent infrastructure gets the resources and careful design it deserves. Furthermore, the talent infrastructure must be able to recruit personnel who are not from the company’s industry to fill talent gaps, engaging, for example, a manager from a financial-services business for a pharmaceutical company.

Health-care giant Sanofi created a dedicated talent center in China to oversee a range of interrelated initiatives that helped, for example, develop a pipeline of middle-management candidates to support its rapid expansion plans. The center supervises leadership training and career development activities; orchestrates talent assessment and young-leader rotation and mentorship programs; and runs recruiting, including relationships with a range of talent sources such as universities.

The business units actively participate in the center’s curriculum design and teaching. And the center operates alongside but not within the local HR function. Training sessions and coaching at the center have increased development opportunities for high-potential talent, as well as the flow of talent to managers at all levels. As a result, Sanofi has significantly accelerated the numbers of “ready now” talent for first-line leadership roles. This has meant an average investment of US$3,000 per targeted employee in 2011, and Sanofi is confident that it will overcome the talent challenges of the Chinese market.

Put the Marketing of Talent Advocacy on Every Executive’s Agenda

At many companies in China, recruiting is owned and executed by HR. It follows a traditional path that starts with advertising and moves through screening applications, interviewing candidates, and convincing the most desirable of them to join.

Imagine instead a process of marketing a product called employment. This process would involve the participation of the entire organization, including senior executives, because every function—and every department—has a stake in the outcome. Just like a managed customer experience, the process starts with awareness and moves through consideration and preference to acceptance. It does not stop when the recruit joins the company. It continues by encouraging employee satisfaction, loyalty, and the endgame: current employees’ advocacy in building the company’s reputation from the bottom up.

Key performance indicators (KPIs) similar to those used to track product-marketing effectiveness can serve to measure the effectiveness of talent management. During the early awareness, consideration, and preference stages, the company can gauge talent pool and channel effectiveness by using China-specific HR data to evaluate emerging pools and the quality of candidates. For the application and acceptance stages, one can track process discipline through recruitment, onboarding, and training data—all benchmarked against industry best practices.

Today, successful advocacy marketing hinges also on the appropriate use of social-media platforms. Young Chinese employees and candidates—who spend an extraordinary amount of time on social-networking sites, blogs, and virtual communities, far more than their counterparts in many other countries—are also heavy users of job search websites.

Senior leaders play an essential role in overseeing all these activities. Introducing talent-related KPIs can have compensation-related implications—sometimes amounting to a quarter of executives’ annual bonus incentives.

Overall, the driver with the greatest impact on an employee’s advocacy of a company is its well-established culture based on meritocracy: people know that they are recognized and rewarded on the basis of their performance, and company managers spend a significant portion of their time developing employees’ performance and competencies. This cannot be a matter of HR systems alone. It is principally a question of executive culture.

Finding and developing top talent on a local basis are prerequisites for success in China—and those processes are becoming increasingly expensive. (See “Are You Really Prepared for China? A Five-Point Checklist,” below.) Giving employees reasons to get truly engaged, to stay with their employer, and to become advocates for the company matters more now than ever before.

Are You Really Prepared for China?: A Five-Point Checklist

Given the extent of the talent shortage in China, it’s essential that senior executives draw up a detailed talent plan well before they enter or expand in the local market. On the basis of our experience, we have prepared questions executives should ask themselves to determine whether the company’s business strategy will protect it from running aground for lack of a talented crew.

Planning. Do we have a quantifiable, multiyear people plan that will anticipate and realistically address the most critical gaps for employees in middle-management and specialist roles?

Employer Brand. Do we identify the rationale and the emotional attributes that will resonate with our target employee segments? Does the company focus on, for example, career advancement, base salary, and company ranking to offer a winning trinity across many sectors in China?

Talent Engine. Do we have systematic processes for funding and building a talent “engine” that allows us to renew 30 to 40 percent of our employee base (turnover plus growth) per year and still focus on people development?

Meritocracy. What is our plan for building a culture of meritocracy—a plan that allows us to raise productivity and retain high performers? (The plan should address the perceived “glass ceiling” of a multinational and the relatively weak talent-development approaches of local companies.)

Managers and HR. Do our managers have an acute awareness of the talent challenge? Are they trained to be (and accountable for being) effective people developers? Do our managers benefit from high-quality HR business partners? Are we ready to leverage social media in our talent strategy in China, with its 256 million social-media users compared with, for example, 147 million in the U.S.?5