With much of the developed world mired in slow growth and fiscal austerity, many companies find the strong economies and rising incomes of certain emerging markets quite attractive. But there’s a catch: talent is increasingly difficult to find and hold onto in such countries as Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC). And the talent shortage will only worsen over the next decades as multinationals pursue their localization strategies and locally based challengers continue their ambitious expansion.

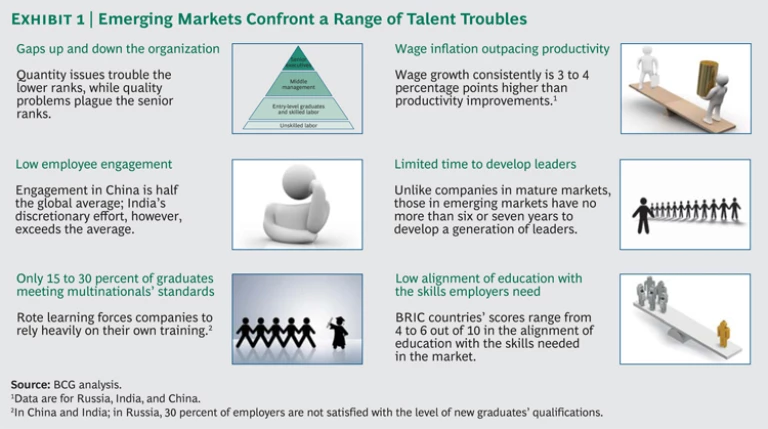

The shortage applies up and down the ranks of employees, though the challenge for employers takes a slightly different shape in each group:

- The numbers of senior leaders may be sufficient, but some may not be fully prepared to cope with the rapid pace of change or the globalizing nature of certain industries.

- Severe supply shortages of middle managers abound, and there is considerable turnover at this level, in part because few companies have focused on developing the skills of their middle managers or offering them opportunities.

- The best talent (consisting of high performers with high potential) is relatively scarce, as there has been little systematic effort to identify and nurture people in this group.

- The graduate pool is expanding more slowly than economic growth in most cases, and only 15 to 30 percent of university graduates are considered immediately employable. Skilled professionals, meanwhile, are constantly solicited to switch employers.

- Competition for skilled workers has intensified in tier 1 cities. And in many remote locations, employers are hard-pressed to find any available skilled operators or technicians.

Companies competing in emerging markets—whether they are multinational or locally based—will, therefore, need to raise their investment in talent management, treating human capital with the same rigor as a capital asset investment in order to overcome some common challenges. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Wage Inflation. Wages have been outpacing productivity in virtually all emerging markets. In India, for example, wages rose at a compound annual growth rate of 9.5 percent from 2000 through 2010, while productivity rose only 7 percent per year. And the most talented employees, who are in demand, are seeking even higher raises than those already significant yearly wage increases.

- Misalignment of Education and Employable Skills. In terms of equipping talent with required employable skills through education, there is an acute quality problem. A recent study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that assessed the alignment of countries’ higher-education curricula with employers’ needs revealed that BRIC countries score from 4 to 6 out of 10, signifying low alignment. Brazil, for instance, ranks fifth from the bottom of a list of 58 countries. People with sufficient technical knowledge often lack the soft skills that companies demand, and in China and Russia, English-language fluency remains weak despite some reported progress.

- Obsolete Cultural and Political Legacies. In Russia, years of communism stifled exposure to consumer priorities and international business experience. Many Russian companies still operate with top-down hierarchies in which employees are reluctant or unable to take responsibility for decisions. In other countries, such as India, the historical dominance of family-owned companies and public-sector enterprises, as well as rigid labor regulations, has left a legacy of rudimentary performance-management systems and thin leadership pipelines.

- Weak Employee Engagement. Various studies of employee engagement in recent years—most measuring self-reported discretionary effort and intent to stay with the current employer—find engagement below the global average in many emerging markets. In China, the engagement level is roughly half the global average. In India, voluntary attrition is running at 19 percent per year and has reached 55 percent in the business-process-outsourcing industry. Weak engagement contributes to high rates of employee turnover, which is both disruptive and costly.

These challenges, while complex, can be addressed with a holistic talent strategy that accommodates regional variations but also maintains an enterprise-wide view. Five aspects of talent strategy merit immediate attention from executives in emerging markets.

Diversification of the Sources of Talent: Tapping New Pools

To attract a broader group of qualified potential employees, companies can look in unconventional places and at alternative groups of candidates. These include decent universities in small cities, expatriates who have studied or worked abroad and are open to returning to their native country, retirees seeking part-time work, immigrants from other countries, candidates from other industries (Indian companies are looking in the defense and government sectors), and young mothers reentering the corporate world. Tata has a career transition program that targets Indian housewives who want to return to paid employment. Diversification also involves taking talented employees from within the organization and giving them several months of specialized training, as Infosys does in India and Neusoft does in China.

Reshaping the talent pool will also require some leaders to change long-standing habits, such as the natural tendency to seek out “ready now” talent rather than viewing recruits as assets to be developed over the long term.

Building Recruitment and Onboarding Engines

A well-designed process for onboarding new employees and starting their career development early on can help cut in half the level of undesired turnover during the first year of employment. Companies have to invest more in education at all levels of the enterprise—in both hard and soft skills and in both on-the-job and classroom settings.

Creating a Meritocracy That Consumes Less Talent and Raises Productivity

Greater productivity does more than just improve the cost structure: it also helps companies manage their talent needs and enriches individual jobs. Reducing the number of people who must be recruited every year hinges on making the current workforce more engaged, more productive, and better organized. Companies can accomplish this through appropriate organization reviews that aim for fewer structures, leaner processes, and performance-based HR systems.

Other types of initiatives may be required to address region-specific issues. In Russia, we have observed a fair amount of arbitrary, unpredictable decision making by middle managers. This tends to corrode engagement levels among employees and stifle productivity. The key to breaking ingrained habits is to develop a meritocracy with clear decision rights and a strong performance-management system based on explicit objectives, feedback, and metrics that link compensation to performance.

Enhancing Middle Management

Building the base of middle-management talent internally has direct economic returns (through lower spending on recruitment) and enhances a company’s value proposition. In high-growth markets, companies have six or seven years at most to develop a generation of leaders, not a decade or more.

Manager development can be accelerated by identifying high-potential employees early on and overinvesting in them through accelerated job rotation, opportunities for project leadership, and a variety of assignments. In a country with a short history of international profit-making enterprises, managers would benefit from significant investment in strategic thinking, effective coaching, and collaborative work with a diverse group of employees.

Professionalizing the Talent Management Approach

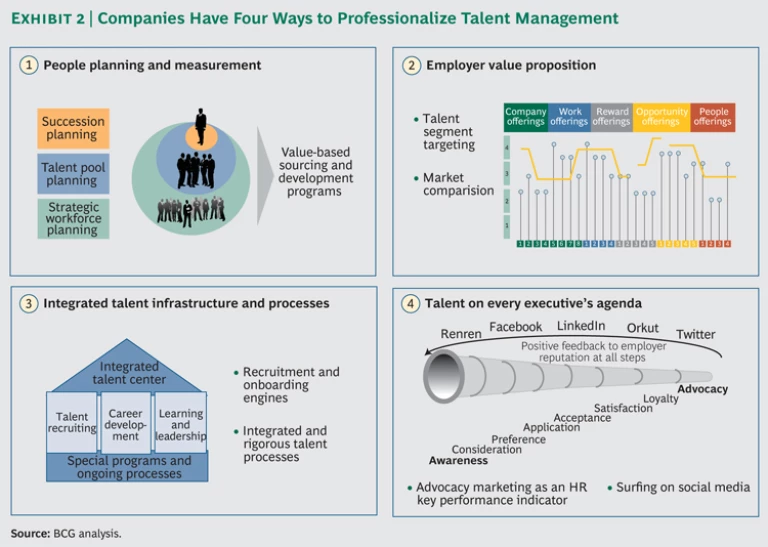

No major company would dream of launching a product without a detailed plan, resources allocated for product distribution, and a marketing campaign. Likewise, talent management should be professionalized along several dimensions. (See Exhibit 2.)

People Planning. An important first step is to systematically assess the company’s workforce-capacity risk for a particular region and then put a strategic plan in place to manage that risk in three areas. The first is strategic workforce planning, which involves projecting current resources and future supply and demand at the job family level to identify the potential gaps as well as the productivity challenges that the company will face. Subsequent actions in recruiting, reorganizing, and outsourcing choices should proceed on the basis of the analysis.

The second area, talent pool planning, focuses on future middle and senior leaders for the company. This requires careful engineering of desired and undesired attrition, career lattices that are more flexible than career ladders, and accelerated progression for promising employees, which is particularly important in high-scarcity markets.

A succession heat map is the third key planning component. Companies must identify the risks for pivotal positions and the internal and external sources from which those positions can be filled. Signals of weak engagement in pivotal roles can be monitored through employee surveys, regular dialogue with supervisors, and even postings on relevant blogs and social-media platforms.

Employer Value Proposition. Once the strategic plan is in place, there is a marketing challenge: defining the company’s brand and value proposition as an employer and marketing that brand through the appropriate channels to target talent segments. This could involve many of the tools familiar to marketers but foreign to many HR managers, including focus groups, voice-of-the-customer surveys, and creative use of social-media platforms to reach the target segments in their favorite channels.

Integrated Talent Infrastructure and Processes. Identifying, recruiting, and developing talent takes time and money—and the bill can easily range from half to all of a year’s salary for certain positions. That’s why it is essential to build consistent and optimized companywide processes for career reviews, performance and compensation management, and learning and development.

Talent on Each Executive’s Agenda. Social media allow recruits and employees to quickly learn about and comment on the day-to-day reality of management and career prospects inside a company. Delivering on the company’s brand promise to employees thus becomes the responsibility of all executives rather than a process owned only by HR. Indeed, the time dedicated to talent management by senior leaders exceeds 10 percent—25 days a year—in the best-performing companies.

The push into emerging markets requires a mix of employees and skill sets that are different from those needed in the past. At the same time, competition for talent is intensifying among local companies and multinationals pursuing localization strategies. These trends put a premium on both attracting and building talent through a coherent professionalized approach—one that puts to rest excessive reliance on poaching and serendipity.