Overview

On the surface, the world’s best organizations may look like many of their competitors: similar kinds of products, comparable business strategies, and related operating models. But put them under the metaphorical microscope, and what you see are distinct combinations of winning attributes.

BCG has recently developed and applied a powerful way to probe more deeply into the makeup of the most successful organizations . The objective of this study was to pinpoint the capabilities that matter most for financial performance, to spot the gaps between best-practice capabilities and those typical of organizations today, and to lay out priorities to help companies close those gaps.

Our survey was comprehensive in scope and scale. We crafted a framework of 20 capabilities that define “organization” in very clear ways, making it more relevant to the everyday experiences of senior managers. We wove the framework into a detailed online questionnaire; our 12 partner organizations worldwide then sent the link to the online survey to many of their members in more than 35 countries.

Business leaders everywhere have similar strategic responses to these concerns. Their top three priorities, according to our study, are about customer orientation, tailoring their products directly to market demands, and establishing leadership in innovation and product quality. “Our most important goal is to be ‘consumer insight driven’ in a way [that is] better than our competitors,” said Bracken Darrell, executive vice president of household appliances giant Whirlpool Corporation and president of Whirlpool Europe.

The survey achieved broad sectoral coverage, too. It canvassed different industries, from consumer goods and health care to financial services and energy, as well as different functions, from support functions such as HR and finance to business functions like product development, manufacturing, and marketing. The respondents were mostly senior executives, including C-suite officers, which underscores the relevance of the topic to corporate success.

The survey itself was not trivial: it required up to 30 minutes from the respondents. The questions covered both the pressing challenges of today’s economy and the internal capabilities needed to secure an organization’s future success. The questionnaire was designed to help us analyze the strengths and needs of respondents’ organizations and to make it simpler to pinpoint the capability gaps in many different dimensions. To complement the results from our large-scale survey and gain deeper insights into selected topics, we also conducted face-to-face interviews with more than 20 senior executives from international corporations.

The study’s findings—laid out in this BCG Focus—yield some striking conclusions. They demonstrate clearly that organizational capabilities drive corporate success. And they reveal that behavioral aspects, often seen as tangential, are vital differentiators—but only when they accompany structural capabilities such as superior organization design and rigorous business processes and controls. A follow-on report explores six factors that are critical to a successful reorganization.

A Matter of Importance: Organizational Attributes

This is not the place to rehash the myriad factors that make today’s economic landscape so bumpy. Suffice it to say that the implications for businesses are profound. Our study confirms that it is increasingly difficult to predict everything from demand patterns to the availability of talent. Executives are quick to enumerate their challenges: More than one-third of those responding to the BCG survey said that increasing competition is what worries them most.

Business leaders everywhere have similar strategic responses to these concerns. Their top three priorities, according to our study, are about customer orientation, tailoring their products directly to market demands, and establishing leadership in innovation and product quality. “Our most important goal is to be ‘consumer insight driven’ in a way [that is] better than our competitors,” said Bracken Darrell, executive vice president of household appliances giant Whirlpool Corporation and president of Whirlpool Europe.

BCG wanted to uncover the fundamental differentiators—the elements in a company’s organizational makeup that would gear the business for enduring competitive advantage. The core question to which we sought answers: How should the management team’s priorities shift, given that the company needs to be more agile, more sharply focused on customers, and better able to mobilize around innovation?

A Comprehensive Framework of Capabilities To start exploring these issues in detail, we developed a framework of 20 discrete organizational capabilities. The framework’s six subcategories address structural capabilities such as the organization structure, layers and spans of control, project management, and business analytics, as well as behavioral capabilities, including leadership performance, employee performance management, and the company’s change-management capabilities. (See Exhibit 1.)

The framework builds upon BCG’s research on high-performance organizations. We began with the characteristics that BCG has found to be typical of organizations that regularly outperform their peers. (See High-Performance Organizations: The Secrets of Their Success , BCG Focus, September 2011.) We then expanded on some of these characteristics to explore more deeply the issue of organizational capabilities, adding an important element of granularity to our assessment. These are the 20 vital topics that we contend should adequately capture organizational performance.

In our first step, we analyzed the correlations between the companies’ current competence in the specific capabilities and their economic performance (charting the combination of growth in revenue and profit margins compared with peers, on the basis of self-reported assessments). This allowed us to identify the topics most relevant to economic success. In the second step, we examined how respondents assessed the future importance of organizational capabilities and compared it with what they said were their current competencies. This contrast allowed us to identify the critical capabilities requiring considerable improvement and significant attention by the top management team.

The Growing Importance of Behavioral Factors

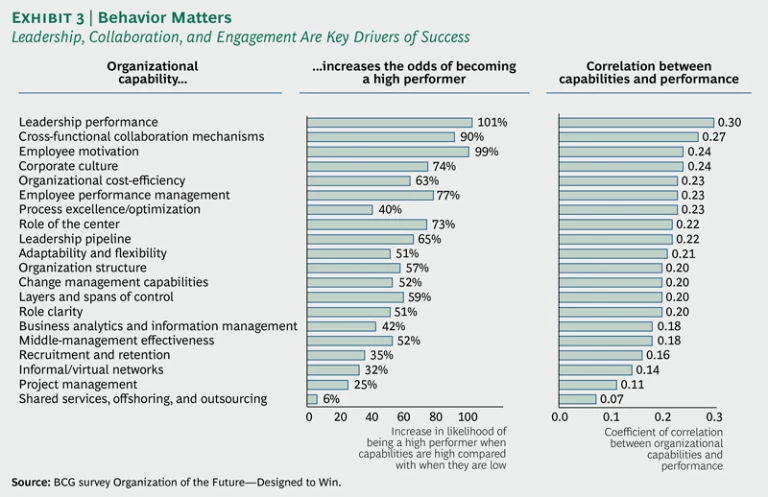

The correlations were revealing. It was immediately evident that all 20 organizational capabilities have an impact on overall performance—though clearly some have much more influence than others. Even more interesting: there is a definite tilt toward behavioral factors—in particular leadership, employee engagement, and cross-functional collaboration.

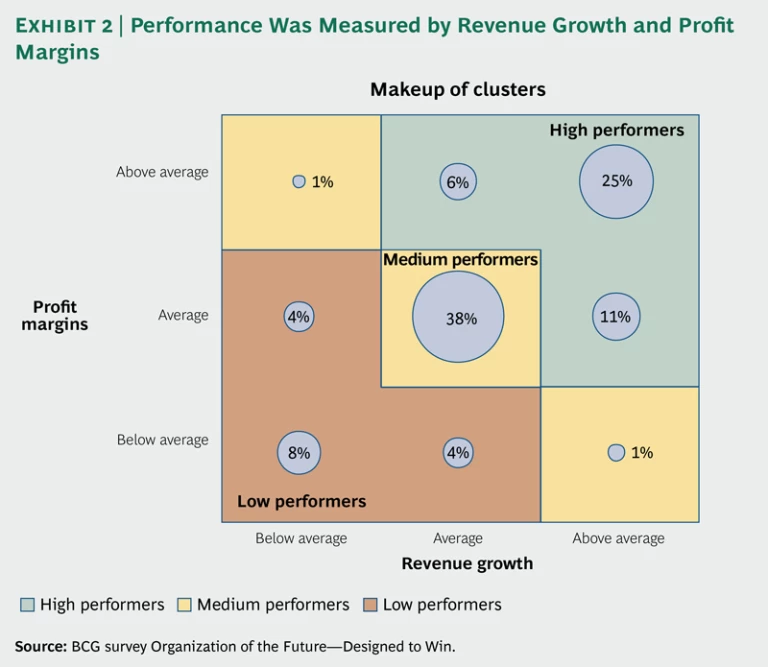

For the purposes of our analysis, we clustered the survey respondents into the segments “below average,” “average,” and “above average” for both measures of economic performance: revenue growth and profit margins. We then classified the respondents into three segments: “high performers,” “medium performers,” and “low performers.” (See Exhibit 2.) Roughly 40 percent of respondents’ organizations turned out to be “high performers” in terms of revenue growth and profit margins; 38 percent were rated as “medium performers,” and about 20 percent were designated as “low performers.” Although this reflects a slight bias in the sample, we contend that the statistical distribution is balanced enough to allow for meaningful correlation analysis between organizational capabilities and overall performance.

Using the framework comprising the three performance buckets, we analyzed the correlation between economic performance and self-reported competence for each of the 20 capabilities. For example, companies that rated themselves high on leadership performance were more than twice as likely to be in the high-performance bucket as companies that rated themselves low on this capability. (See Exhibit 3.) Similarly, effective collaboration across functions and a motivated workforce also drive the likelihood of high performance. These findings were corroborated by the results of an additional correlation analysis between the respondents’ ratings of capabilities and performance: all three capabilities correlated highly with the organization’s overall performance.

The hallmarks of best practice thus snap into focus: what best enables organizations to succeed is a motivated, cross-functional workforce that is led by a highly capable, adaptable, and far-sighted executive team. Efforts to develop these capabilities are likely to pay off in performance that outstrips that of competitors.

The results of our statistical analysis align well with respondents’ perceptions of their own organizations. We asked them about the perceived future importance of the different organizational capabilities. The results point in very much the same direction as that revealed by our analysis. (See Exhibit 4.)

Overall, 77 percent of respondents see behavioral themes as very or extremely important in the years to come, while 63 percent emphasize the importance of structural themes. Companies obviously consider it highly important to react to change in flexible ways: more than 80 percent of respondents put a premium on adaptability and flexibility, and 78 percent said they prize change management capabilities. Similarly, respondents pointed to the future importance of a highly motivated and effectively led workforce (with 82 percent listing “employee motivation” as an important theme, and 83 percent “leadership performance”).

What’s especially interesting is the lower importance assigned to some classical structural capabilities, such as layers and spans of control, role of the center, shared services, and organization structure. Survey respondents perceived most of these capabilities to be less important to the organization’s performance than they actually are, as gauged by their statistical correlation with performance.

Our executive interviews helped us understand what might be causing this potential “underappreciation” of classical structural themes. The interviewees made it apparent that they consider structural capabilities not as differentiators as such, but as enablers. Put simply: without structural factors such as organization structure and cost-efficiency, the behavioral factors would be markedly less effective. Indeed, we found a significant correlation between structural and behavioral capabilities. It is therefore fair to say that structural levers act as the necessary foundation on which companies can deploy the behavioral capabilities that differentiate them from their peers.

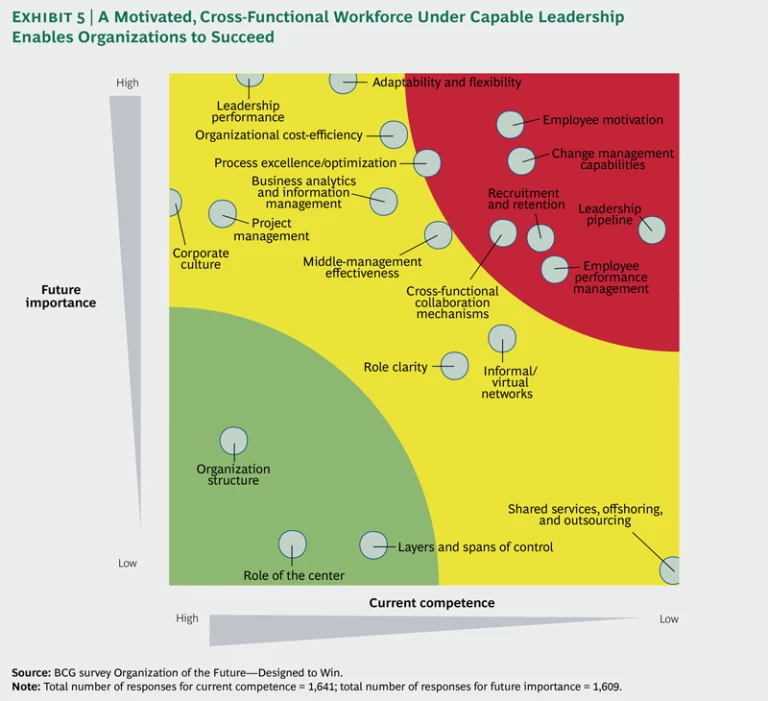

Another part of our analysis involved plotting the impact of the 20 capabilities on future importance against the current competencies of the respondents’ organizations. (See Exhibit 5.) The zone in red—denoting high future importance and low current competence—clearly indicates a need for improvement. Interestingly, in this area we mainly find the core behavioral competencies, such as motivation, collaboration, and change management. We also find topics related to the management of employees—for example, recruitment, retention, and performance management.

So there are plainly big gaps between how senior managers perceive the importance of behavioral and people management capabilities and how they rate their own organizations on those capabilities. These gaps constitute a major challenge for many companies. Organizational excellence cannot be achieved merely by optimizing formal structures, setting up new rules, and detailing organizational role mandates. Companies must now foster cooperation, the exchange of best-practice ideas, and employee engagement to fill the formal structures with life. They have to make continuous efforts to ensure that their behavioral patterns match their needs rather than emphasizing the one-off initiatives intended to attain stability. We will address the transformation road maps in our follow-on Focus report.

The Gap Between Current Practice and Best Practice

What the survey made clear is that for most companies, there is a substantial gap between their organizational capabilities and those that represent best practice—the capabilities that the high performers described as being important for the future. There’s clearly a gulf between aspiration and implementation; business leaders’ awareness that organizational capabilities matter does not automatically translate into how their own organizations behave.

Our data indicate that the behavioral capabilities of many organizations are still inadequate for the upheaval ahead. Leadership pipelines are thin and sporadic. Far from becoming more engaged at work, employees increasingly indicate that they feel discontented and less comfortable in their workplaces.

The Way Forward: Capabilities to Build, Actions to Take

So how can companies close the gap between awareness and action? A new approach to organizational performance is required. Our findings point to three priorities that, when assessed and appropriately acted upon, will produce significant gains in performance: bringing behaviors to the fore; aligning and improving people practices; and ensuring that the company’s structure is aligned with its business strategy. Each merits a closer look.

Bringing Behaviors to the Fore

Our research determined that three behavioral facets deserve immediate attention: leadership, employee engagement, and collaboration.

In our study, leadership performance was consistently perceived as one of the most important organizational topics across all industries, company sizes, and geographic regions. It is all the more critical in times of economic turbulence and increasing complexity in the business environment. In this context, effective role models matter more than formal and strict rules. In particular, adaptability has to be practiced and consciously modeled by the top management team so that it cascades down through the organization.

Even the companies that perform better need to pay particular attention to potential weaknesses in their leadership pipelines. Fully 37 percent of respondents in our survey said that without the development of the required leadership and succession pool, high-quality leadership performance cannot be assured. BCG’s studies of leadership make the point that a core leadership skill is the ability to track and progressively strengthen the capabilities of the next generations of leaders. (See “ New Leadership Rules: Requirements for the Future ,” BCG article, May 2010.)

A second aspect of bringing behaviors to the fore is to attain high employee engagement. It is an article of faith that a truly engaged workforce will perform better by almost every calculation: productivity, product quality, innovation, customer service, ease of retention, and more. Further, without a motivated and diligently recruited workforce, a company will not be able to leverage its other competencies—project management, for instance—to their full extent. Indeed, engagement is essential if companies are to be able to rely more on their employees to adapt to volatility and handle complexity.

BCG’s research has found a strong correlation between authentic leadership and high employee motivation. Just as the ratio of top-performing companies was higher among the organizations that rated themselves as having “top leadership competencies” than among the companies conceding less robust leadership attributes, so it is with employee motivation. The linkage demonstrates the pressing necessity for companies to excel concurrently in both disciplines.

The third facet—collaboration—spotlights the ability of a company’s adaptive leaders to concentrate on sustainable success for the company’s stakeholders as well as for the company itself. (See “Henkel Adhesive Technologies: Assembling Collaborative Capabilities,” below.) Those leaders build platforms for collaboration, exploiting technology to enable large groups to tackle complex tasks, such as product innovation, across boundaries of organization, geography, and time. Cristóbal Conde, former CEO of software and service provider SunGard, put it this way: “A CEO needs to focus more on the platform that enables collaboration, because employees already have all the data.”

Henkel Adhesive Technologies: Assembling Collaborative Capabilities

Henkel Adhesive Technologies is a $10-billion-a-year leader in the global industrial-adhesives market, serving a broad range of industries with adhesive, sealant, and surface treatment solutions.

The company faces a host of technology challenges as well as growing health and environmental demands, which collectively add complexity to the product and application portfolio. Henkel also faces competition on many fronts. In specialty adhesives segments, where asset intensity is low and application expertise has to be high, the company goes head-to-head with many small and nimble competitors, most of which are highly specialized or firmly established in local areas and some of which are new—especially in emerging markets. Henkel also competes in bulk volume segments against vertically integrated chemical companies that are exploiting their access to volatile raw-material markets to expand down-stream into the adhesives business.

Henkel’s response has been to formulate and roll out a powerful innovation strategy. The strategy calls for a rebalancing between short-term product adaptation and ambitious long-term “breakthrough innovation” projects. The strategic reprioritization was translated into new target behaviors that called for more risk-taking and more entrepreneurial thinking from the leadership team, combined with a willingness to place larger bets while staying focused on short-term projects and customer support.

The behaviors also required greater engagement from employees at all levels and in all functions in order to identify new opportunities and generate new ideas, and prescribed increased collaboration across functions, regions, and business units so that new ideas could be shared easily and alliances could be formed to push and implement those ideas.

Henkel identified and activated a broad set of organizational levers to make the necessary changes happen. The company structured a new cross-business-unit research platform into which hundreds of researchers were transferred; the purpose of the new platform was to lead the big long-term breakthrough projects and allow more leverage of technology across the business units. The research that remained in the units was refocused around specific product development—particularly on short-term reformulations, commercialization, and adaptation. Product development sites were consolidated to develop critical mass and improve collaboration.

At the same time, Henkel redefined its innovation-management mechanisms and budget responsibilities so that the business units would be responsible for maintaining high-value innovation pipelines. The business units would individually hire capacity on the research platforms to push their long-term projects forward, and each unit’s innovation manager would monitor the progress of the platforms in his or her unit. In addition, an independent advanced-technology group was set up to drive research on next-generation materials—the kinds of materials that were well beyond the scope of the units’ own research efforts. Planning processes, KPIs, and tracking mechanisms were redefined, and the company initiated a change cascade, using workshops to explain the new strategy and structures and lay out the behaviors required from leaders and researchers. New platforms for idea exchange and collaboration were put in place, and success stories were widely communicated. A lot of attention went into defining new roles and matching the right talent to the right roles. Critical capability gaps were identified and addressed through training, coaching, and recruiting.

As a result of its innovation initiative, Henkel dropped hundreds of less promising smaller projects and placed several larger bets on new technologies. Innovation became a central topic in management reviews and executive committees, and morale in the R&D organization improved significantly, despite difficult and contentious structural changes. The company’s organic growth has accelerated and the quality of its innovation pipeline has improved dramatically.

At the same time, collaboration mechanisms inspire behaviors that reduce the need to add structural complexity. By creating an environment conducive to collaboration, a company can avoid adding dotted lines to its organization charts. By curtailing complexity in this way, the company is freer to respond more easily to changes in its markets.

Alighning and Improving People Practices

On the whole, people practices are ripe for improvement everywhere. In our study, the HR function was mentioned frequently as the least effective of all functions. That raises questions about HR’s ability to help build the employee skills and competencies that drive high-performing organizations. Although line managers are primarily responsible for leadership competencies and employee engagement, HR’s current underperformance merits attention from senior management.

In Creating People Advantage 2011, we noted that HR can do more to improve the clarity of its mission, streamline its organization, upgrade its talent, and strengthen its governance. Given that behavioral and people management competencies are critical for economic success, there is an urgent need for action by HR leaders.

Another impetus for action is our finding that those outside HR often see the function in less favorable terms than HR itself. The biggest difference lies in the perceived ability of HR to attract the best talent, develop skilled employees, and consistently motivate them to deliver high performance. These results are in line with findings from other BCG studies, which show that these critical HR processes often fall short of their objectives and fail to provide added value for their organizations.

There’s ample room for HR to bolster the gamut of people capabilities—from reenergizing talent acquisition and management to rethinking career paths and incentive systems. It’s also necessary for the organization to properly harness the intellect and energies of its employees—in essence, sparking far higher levels of engagement.

Ensuring That Structure Aligns with Business Strategy

As noted earlier, behavioral and people management factors have a great impact on an organization’s performance. Yet if there’s no firm foundation in structural capabilities, don’t expect wonders from improvements in behavioral traits by themselves. Imagine the difficulties that could surface in an organization that lacks the appropriate structural mechanisms. The lack of clear organizational boundaries and processes would likely breed a corporate culture that would be unconstructive to the point of being deeply negative. Employees’ energies would be consumed with trying to create order—and perhaps with blaming others for their predicaments.

Similarly, the organization has to provide the structural underpinnings that will accommodate different leadership archetypes as market circumstances shift. For instance, when an industry matures and becomes more stable, the organization should be able to field the sensing and information systems needed to support a more analytical style of leadership. But in more volatile times, the organization may need to be able to create loosely coupled networks of partners when a more experimental leadership style is needed. (See “ Adaptive Leadership ,” BCG Perspectives, December 2010.)

The businesses that perform at the highest levels see the connections between having the right behavioral capabilities and having a concrete basis in structure. Our data show that the companies that excel on the structural front are also always ahead in terms of their behavioral capabilities. Generally speaking, a sound structure can drive leadership, collaboration, and engagement. Just one instance: the high performers never treat organization design as an afterthought; they have a solid grasp of the interactions among the three elements of organization design—structure, individuals’ capabilities, and roles and collaboration. (See Demystifying Organization Design: Understanding the Three Critical Elements, BCG White Paper, June 2010.)

Clear accountabilities, unambiguous decision-making rights, and lean and cost-efficient processes enable employees to engage and cooperate, freeing them from bureaucratic entanglements and internal turf wars. Maintaining a structure with the fewest possible layers and higher spans of control reduces micromanagement and empowers employees—especially middle managers. Clarifying roles and accountabilities reduces duplicate work, accelerates decision making, and fosters ownership. Process discipline focuses energy, reduces the cost of coordination, and provides an avenue for improved flow of the information critical for decision making.

It is encouraging that most of the executives we interviewed recognize the importance of combining both behavioral aspects and structural interventions. They clearly understand that structural issues do require attention. Fully 79 percent of respondents described the importance to their organizations’ future of cost-efficiency and process excellence, for example. Yet there is a risk that managers underestimate the need for action and overestimate their capabilities. Most respondents stated that the traditional structural themes of organization structure, layers, and spans of control, as well as the role of the corporate center, do not require any improvement in their companies. Similarly, project management and process excellence were perceived as adequate.

In some cases, their assessments might reflect the truth. In others, the managers might be too complacent or indulgent toward their organizations. Just as behavioral factors need continuous attention, the very structural foundation of an organization’s performance needs a regular “health check” to ensure its solidity and robustness. Otherwise, the organization’s performance risks gradual deterioration.

Clearly, it is no overnight fix to identify the necessary organizational capabilities—let alone to augment and implement them. The development and sustenance of the right mix of organizational capabilities are never something that can be achieved in this financial quarter, or even within the span of a fiscal year. That is especially true of behavioral capabilities. So business leaders must view the necessary changes as a journey rather than as a one-off project designed to achieve some kind of steady state.

Nor is there one true set of themes that will apply to every company in every industry; what works for a midsize retailer in Brazil is rarely likely to work for a large machine-tool manufacturer in Japan, for example.

But this does not mean that the issue of organizational capabilities can be put off to another day. BCG’s findings make it abundantly clear that there is a cast-iron connection between robust, well-articulated organizational capabilities and business performance. That connection will not be lost on shareholders. The issue has to become an agenda item at the next C-suite meeting.

To be sure, it is still a huge step to move from intent to implementation. Now that there is a better platform for understanding the elements of organizational performance, we can tackle the question of how to actually transform the organization in order to achieve it. In the second report in this series, we will draw more deeply on BCG’s new research to explain what is involved in making such transformations successful.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to offer their sincere thanks to Tim Horlacher, Sebastian Kempf, Max Kneissl, Cleo Race, Steve Richardson, Teresa St Clair, Willis Taylor, Nora Tophof, and other BCG colleagues for contributing their insights and for helping to draft this Focus report.

Study Partners

Global study partner: The Conference Board The Conference Board is a global, independent business membership and research association working in the public interest. Our mission is unique: To provide the world’s leading organizations with the practical knowledge they need to improve their performance and better serve society. The Conference Board is a non-advocacy, not-for-profit entity holding 501 (c) (3) tax-exempt status in the United States. Human Capital research at The Conference Board focuses on people-related research and ideas that develop talented and engaged workforces, driving shareholder value and benefits to society.

AAoM – Asia Academy of Management The Asia Academy of Management is a global organization that welcomes both ethnic Asian and non-ethnic Asian researchers and managers who are interested in management issues relevant to Asia. The mission of the Asia Academy of Management is to assume global leadership in the advancement of management theory, research and education of relevance to Asia.

AMA – American Management Association American Management Association

(

www.amanet.org

) is a world leader in talent development, advancing the skills of individuals to drive business success. AMA’s approach to improving performance combines experiential learning—learning through doing—with opportunities for ongoing professional growth at every step of one’s career. Organizations worldwide, including the majority of the Fortune 500, turn to AMA as their trusted partner in professional development and draw upon its experience to enhance skills, abilities and knowledge with noticeable results from day one.

CII – Confederation of Indian Industry The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) works to create and sustain an environment conducive to the growth of industry in India, partnering industry and government alike through advisory and consultative processes. CII is a non-government, not-for-profit, industry led and industry managed organisation, playing a proactive role in India’s development process. Founded over 116 years ago, it is India’s premier business association, with a direct membership of over 8,100 organisations from the private as well as public sectors, including SMEs and MNCs, and an indirect membership of over 90,000 companies from around 400 national and regional sectoral associations.

CMI – Chartered Management Institute CMI is the only chartered professional body dedicated to raising standards of management and leadership across all sectors of UK commerce and industry. CMI is the founder of the National Occupational Standards for Management and Leadership and sets the standards that others follow. As a membership organisation, CMI has also been providing forward-thinking advice and support to individuals and businesses for more than 50 years. CMI is committed to equipping individuals with the skills and knowledge to be exceptional managers and leaders. Through in-depth research and policy surveys of its 90,000 individual and 450 corporate members, CMI maintains its position as the premier authority on key management and leadership issues. Find out more at www.managers.org.uk .

GFO – German Society for Organizational Topics The German cooperation partner in the study is the German Society for Organizational Topics—Gesellschaft für Organisation (gfo) e.V. With its expert meetings, exhibitions, and congresses, its online knowledge base and its journal, the society represents the leading platform both for its members and for anybody else interested in organization and management. For more information, please visit www.gfo-web.de .

IBGC – The Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance The Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance (IBGC) was founded on November 27, 1995, as a non-profit organization. It operates in Brazil and abroad with the aim of inspiring excellence in corporate governance. Through its activities as a knowledge center on the subject, the Institute runs courses, surveys, lectures, forums and an annual conference, among other activities in the corporate governance sphere. Headquartered in São Paulo, the IBGC operates regionally through four Chapters: MG, Paraná, Rio and South. For further information, go to the IBGC website, www.ibgc.org.br .

ÖVO – Austrian Society for Organization and Management The Austrian Society for Organization and Management—Österreichische Vereinigung für Organisation und Management (ÖVO)—is a private nonprofit institution that strives to form and build the image of organizational work. It was founded in 1981 with the dual objectives of spreading organizational knowledge through expert discussions, workshops, and seminars, and linking science and practice. For more information, please visit www.oevo.at .

SGO – Swiss Association for Organization and Management The Swiss Association for Organization and Management—Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Organisation und Management (SGO)—was founded in 1967 by the heads of several leading Swiss companies and organizations. Today, the SGO, which is located in Zurich, has more than 1,600 members. Together with the ASIO (Associazione Svizzera Italiana d’Organizzazione e Management) and the ASO (Association Suisse d’Organisation et de Management), the SGO can reach more than 2,300 Swiss members. For more information, please visit www.sgo.ch .

Afope – The Institute of Organization in Business L’Afope, the Institute of Organization in Business, serves organization specialists, internal consultants, and managers to enhance organizations and hence company achievement. Afope promotes and develops the role of organization within businesses. Afope improves the skills and expertise of managers and organizational practitioners in business, as well as organizational performance.

RMA – Russian Managers Association Russian Managers Association (RMA) is an independent non-government organization working in the best interests of the Russian executive managers’ community. RMA collects and disseminates best management practices and knowledge, thus helping Russian businesses to meet international business standards and ethical rules. Through constructive dialogue between the public and private sectors, RMA improves the image of Russian business and fosters Russia’s integration into the world economy. For more information, please visit www.amr.ru .

JMA – Japan Management Association From industry to organisation, the JMA supports management innovation in various fields. Through our members, Board of Directors, Advisory Councils and trustees, we work to ascertain the needs of all parties, contributing to the development of Japanese enterprises. At present, we are focused on management innovation in a variety of fields, not only for organisations but also for municipalities, educational institutions, hospitals and other public institutions according to four main themes. For more information, please visit

www.jma.or.jp

.