Digital’s disruption of the consumer goods and retail industry, already severe, will only increase in speed and magnitude as annual worldwide e-commerce revenues double to $1.5 trillion by 2015. New levels of connectivity, the proliferation of new technologies, the rapid growth of new business models, and the rise of advocacy marketing and social shopping all add fuel to the digital fire. These changes are creating enormous value for some players—online marketplaces such as Amazon and Taobao, for example—while putting others, on both sides of the retailer-supplier equation, under acute pressure to adapt.

This article, the first in a series on what these developments portend, looks at the changes under way—as well as those on the horizon—and the challenges and opportunities they present.

The retail industry and its consumer goods suppliers are nearing the apex of the third of four overlapping waves of e-commerce development and disruption. The first two groundswells have already led to a significant shakeout. The third is causing further widespread upheaval, and the fourth, which has yet to approach critical mass, has the potential to be the most disruptive yet.

Initial Waves of the Digital Revolution

In the first wave, long-tail catalogs of products with hundreds of thousands of SKUs—music, movies, books, video games, software, event tickets, and the like—moved online. Consumers jumped at the convenience and selection as retailers such as Amazon, Napster, and eBay provided significantly broader assortments at much lower distribution costs. Many brick-and-mortar retailers, including household names such as Blockbuster and Tower Records, closed up shop. Media publishers retooled their product offerings—often reviving back catalogs—and revamped distribution to fit a digital world. New partnerships between these content suppliers and electronic distributors and retailers took root. The digital retail revolution was off and running.

Wave number two saw the online migration of a broad array of general merchandise, such as electronics, computers, toys, office supplies, and specialty goods and apparel—easy-to-ship products selling at price points of $20 or higher. Pure-play e-commerce companies expanded into multiple categories, and online specialty retailers such as Zappos started to take share with such policies as guaranteed satisfaction and free returns. In the brick-and-mortar world, so-called category killers felt the impact, and showrooming took hold, especially in electronics. Many traditional retailers began to invest in multichannel operations to protect market share. Manufacturers of consumer goods in these categories established full-scale distribution partnerships with online players, and some, such as Nike and Victoria’s Secret, launched their own direct-to-consumer e-commerce businesses, which became big successes.

Seismic Shifts

The driving force behind the third wave has been the rise of online marketplaces, which allow thousands of third-party vendors to sell goods through common merchandising and payment platforms in exchange for a commission, oftentimes while the marketplace sells its own inventory as well. Under this model, Taobao, Rakuten, Amazon, and others are taking huge and growing portions of sales in many markets. In 2011, Amazon had a 12 percent online share in North America (up from 10 percent in 2010); Taobao, 80 percent in China; and Rakuten, 30 percent in Japan. These platforms will drive e-commerce growth to well over $1 trillion in annual sales.

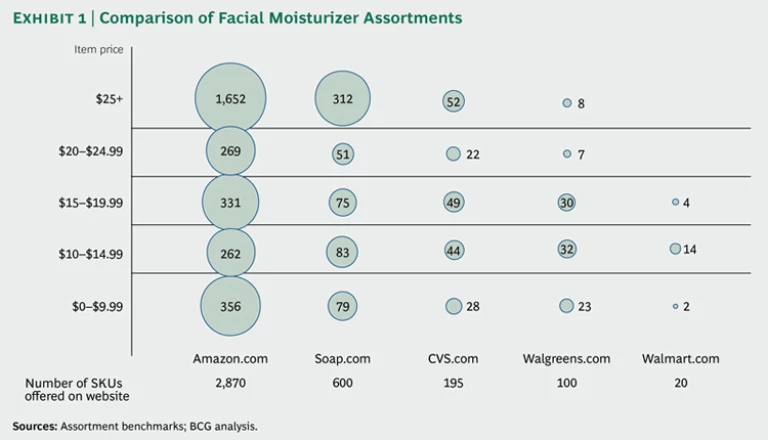

From the consumer’s perspective, online marketplaces offer near endless assortments, sometimes up to 80 times that of traditional retailers, even in categories outside traditional strongholds such as books and electronics—facial moisturizers, for example. (See Exhibit 1.) They also offer unprecedented price transparency and competition among vendors. Online marketplaces are exploiting the increasing ubiquity of mobile devices with apps that allow consumers to compare prices and purchase anywhere, anytime. Marketing and pricing innovations such as free shipping (Amazon Prime and Tesco Delivery Saver, for example) build customer loyalty, and the resulting volume leads to economies of scale that reduce infrastructure and logistics costs and improve negotiating positions with downstream providers.

In addition, by aggregating third-party inventory, online marketplaces spread the cost of customer acquisition across thousands of sellers. In some cases, they are acquiring their most successful sellers, gaining footholds in new categories. Amazon’s purchase of Quidsi, which operates an array of consumer-targeted sites such as Diapers.com and Soap.com, is one example. The result is unprecedented: retailers with annual sales on a magnitude of $50 billion growing at rates of 40 to 50 percent per year.

In the fourth wave, just in its infancy, several trends converge. First, dry groceries and other inexpensive fast-moving consumer goods, long the purview of brick-and-mortar stores, will move online. In South Korea, the penetration of online grocery so far is approximately 11 percent; in the U.K., it is approximately 6 percent—up from 1.5 percent in 2006. We expect other markets to follow suit as online marketplaces and “click and mortar” operations improve the consumer experience and bring down the cost of delivery through improved warehouse technology, subscription purchases, bundled or “add on” items, and, perhaps most significantly, new services such as “click and collect.”

The rise of click-and-collect services—the second major trend—enables consumers to order a basket of goods on their computer, tablet, or smartphone and pick it up at a store or dedicated facility. These services are gaining popularity in many markets, particularly where home delivery is problematic. Major grocers in France, including E.Leclerc and Auchan, will have established some 1,200 click-and-collect sites, many operated as “drive throughs,” by the end of 2012, fueling online sales growth of 25 percent per year through 2015. In the U.K., Tesco.com began offering click and collect in 2011 and saw a 30 percent increase in online nonfood sales over 2010. Likewise, Walmart.com now estimates that half of its online orders in the U.S. are picked up in stores.

The main challenge for retailers will be executing profitably, particularly when the picking of goods takes place in existing or “dark” stores (stores closed for walk-in shopping but used by employees to prepare customers’ orders). While some retailers have opted to charge convenience fees, others are using technology and optimized warehouse footprints to reduce costs.

One variant of this model, which has been employed by online pure players, is delivery from centralized distribution facilities to “parcel lockers”—temporary storage facilities in convenient locations where individual online orders are held for pickup. These are gaining momentum in several countries, including Denmark, Russia, and Turkey. Amazon piloted the concept in New York, Seattle, and London and has now expanded to additional markets such as San Francisco and Washington. We estimate that parcel lockers can reduce the cost of delivery by as much as 30 to 40 percent compared with direct delivery to the home, thus significantly improving retailers’ economics for fast-moving goods.

Omnichannel retailing—the interaction of consumers and retailers anytime, anywhere, on any kind of digital device—is another major trend that is growing in importance. It is being driven by multiple factors, primarily the explosion in mobile and other interconnected devices. Annual smartphone sales are estimated to reach 935 million units globally by 2015, while tablet sales will reach 370 million units in 2016.

Although mobile commerce will remain a relatively small portion of total e-commerce (approximately 10 percent), this interconnectedness is enabling “e-influence”—shoppers researching online but purchasing in stores—like never before. Already, three-quarters of smartphone users have said that the research they performed on their device resulted in a purchase. We expect this number to grow, particularly as CRM and targeting technologies continue to improve, and as marketers can deliver ever more targeted and timely messages, such as ads for sports drinks or running gear minutes after somebody tweets about completing a run.

The ubiquity of mobile computing is propelling the rise of social shopping. The number of Facebook users has passed 1 billion (one-seventh of the world’s population). More than half of millennial consumers report using social media to check out brands. Already, the number of people following some celebrities’ Twitter feeds has surpassed the population of major countries.

Tapping into these networks will give brands and retailers the opportunity to reach consumers in new environments, interact with them in innovative ways, and create entirely new shopping experiences and occasions, all of which will evermore blur the lines among retailers, suppliers, and media—and, of course, between the online and offline experience.

Pressing Issues for Retailers and Suppliers

These changes have major ramifications for both retailers and consumer goods suppliers. New rules, changing economics, and evolving success factors will lead to new sets of winners and losers.

For retailers, longtime drivers of the industry’s economics—sales per store and gross margin per square foot or meter—are giving way to new criteria, revenue and margin per household being the most significant. While success to date has been determined by optimizing the tradeoff between selection and store size and density, the competitive playing field increasingly will be shaped by the following factors:

-

Identifying the right online-marketplace strategy (that is, beat them or join them)

-

Defining profitable omnichannel strategies, including the roles of online, mobile, social, and brick-and-mortar in the purchasing pathway

-

Optimizing use of the “three Cs” of commerce/content/community across channels to drive traffic and provide consumers with the right information at the right time

-

Establishing effective cross-channel assortment and pricing mechanisms, including finding unique products to attract customers (for example, by introducing exclusive brands) and designing effective pricing-per-customer models (such as loyalty-based “subscribe and save” programs)

-

Managing physical footprints aggressively, including designing smaller formats, rethinking store profitability, and finding ways to monetize the “showroom”

-

Resegmenting the customer base and optimizing promotional spending across traditional and emerging channels—in particular, quantifying customer lifetime value and acquisition costs across various media

-

Future-proofing distribution networks by upgrading warehouse technology and determining the optimal fulfillment click-and-collect model for different types of products (for example, shipping from stores versus shipping from distribution centers)

Developing the organization model and analytical skills to build the most compelling digital presence (including reframing traditional key performance indicators)

The challenges for suppliers are no less significant or far-reaching. Online commerce presents both opportunities and risks, and the mix is different for each company and brand, depending on such factors as the concentration of current distribution channels, the potential of online channels, and brand strength and customer loyalty. Some issues that suppliers need to address:

-

Revisiting channel strategy (including prioritizing emerging channels—for example, e-commerce, e-retailing, and online marketplaces—while addressing potential conflicts)

-

Deciding the roles of the company and brand websites and mobile applications in the purchasing process

-

Managing pricing conflicts and transparency—and identifying the right assortments across channels, including exclusive and overlapping offers

-

Updating in-store merchandising plans to take advantage of excess retail space created by categories that have lost relevance in stores

-

Reworking marketing strategies to take account of new online and mobile buying segments (such as millennials) and vehicles (social and advocacy marketing, for example)

-

Upgrading the digital supply chain (including resolving make-versus-buy decisions and developing distinct packaging for online products)

-

Designing the digital-ready organization with integrated processes and new KPIs (such as “digital” key account management)

Investing in digital infrastructure, including the ability to draw insights from “big data”

In subsequent articles in this series, we will explore some of the specific challenges facing both retailers and suppliers.

No Time to Waste

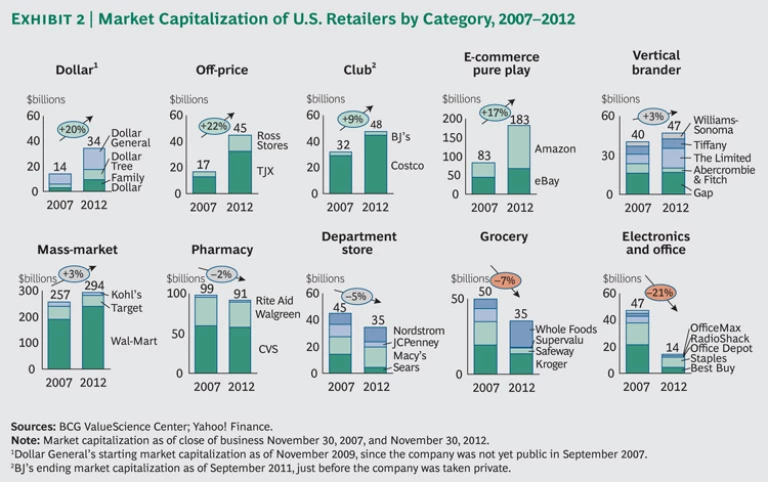

The first few waves of the digital revolution have upended the retail industry. The coming changes promise even more turmoil. Financial markets are assessing prospects for both industry sectors and individual companies—and their judgments are being felt in the addition or elimination of billions of dollars of market capitalization. (See Exhibit 2.) There is no time to procrastinate: retailers and suppliers need to embrace these changes and move forward with their digital strategies now.