Four waves of e-commerce disruption are sweeping across the consumer goods and retail industry. The third and the biggest so far, the rise of online marketplaces, is nearing its apex. It is transforming retail economics, creating enormous value for some players and huge challenges for others. This article looks at the drivers of success behind, and the impact of, one of the most far-reaching online phenomena.

Retail regularly undergoes transformation. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was the rise of department stores. In the twentieth, first catalogs and mail order, then big-box stores and hypermarkets, changed how consumers—particularly Western consumers—shop. The first radical wave in the twenty-first century—online marketplaces—is upending the sector again, and doing so with unprecedented speed and reach. Companies such as Amazon, Rakuten, and Taobao, among others, have built commanding market shares in just a few years and are still growing fast. Amazon is already a roughly $50 billion business and growing at 40 to 50 percent per year. The gross value of merchandise sold on Rakuten has doubled since 2007 to more than ¥1 trillion. Marketplaces will drive e-commerce growth to well over $1 trillion in annual sales in a few years’ time.

As with previous upheavals, this phenomenal success is rooted in consumer choice, convenience, and transformative economics. On the basis of their successes in books and electronics, the pioneers of online merchandising (Amazon was founded in 1994; Rakuten, in 1997) realized that by enabling thousands of third-party vendors to sell goods through common marketing and payment platforms, they could create significant value for all the parties involved—consumers, sellers, and the marketplaces themselves.

Benefits to Consumers: Choice and Transparency

Online marketplaces provide substantial benefits to consumers. First among them is the depth and breadth of goods available. Our analysis of a dozen product categories spanning pet supplies, electronics, personal care, diapers, and groceries shows marketplaces offering selections up to 80 times as large as those offered by traditional pure-play and multichannel retailers. Marketplaces also give consumers access to low-volume and niche products not always available elsewhere.

In regions where the physical retail infrastructure is not well developed, marketplaces often provide the best access to merchandise. As one Shanghai consumer told the Wall Street Journal, “I would say 90 percent of the things in my house” were purchased on Taobao, including “the washing machines, the air conditioning, the television, the

Some might think that consumers are overwhelmed by this breadth of choice. The reality is that consumers who want to “beat the system” and younger generations (especially the 18- to 34-year-old Millennials) value marketplaces precisely for the wide selection they offer and because marketplaces have become adept at serving up the most relevant products to consumers through their knowledge of individuals’ preferences.

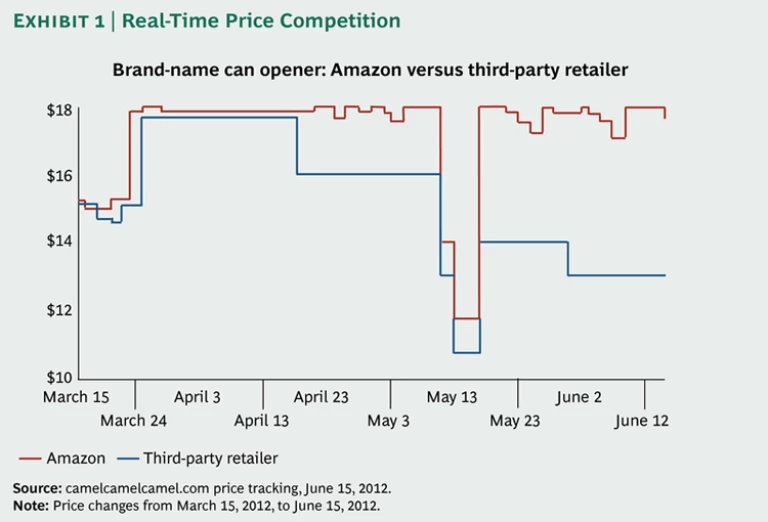

Consumers also benefit from transparent and dynamic pricing. From hard drives to shampoos, marketplaces consistently offer better prices than multichannel retailers—discounts of up to 80 percent in some cases. The reason lies partly in advantaged economics (lower real-estate and operating costs, for example) and partly in competition: dozens of vendors often vie to sell the same item, algorithmically adjusting prices up and down in real time. One high-end brand-name can opener, for instance, showed price fluctuations of up to 60 percent ($10.75 to $17.99) over three months. (See Exhibit 1.) Couple this with the third-party tools that allow consumers to set price alerts, and you have a situation where shoppers can command the lowest possible price with just a few clicks.

A third advantage for consumers is innovative loyalty offers that seek to cement the customer relationship and generate continuing streams of business. Amazon Prime offers such benefits as free shipping in return for an annual subscription fee ($79 in the U.S.). The strategy is time-tested: use subsidies to capture a greater share of consumers’ wallets. Many analysts have questioned the long-term sustainability of such programs, but we believe the economics benefit the marketplace. Our estimates—based on an analysis of customers’ order histories before and after joining one loyalty program—show a fourfold increase in the number of purchases and a twofold jump in overall gross profits in the first year of membership, despite a noticeable increase in the number of money-losing orders.

Benefits to Sellers: Access to More Markets and Consumers

Marketplaces work because they offer benefits to sellers as well. Companies gain access to new markets and new customers with minimal incremental investment in marketing. They have the opportunity to sell direct, many for the first time, eliminating one or two middlemen. The cost is only a variable commission, usually between 8 and 15 percent of sales through Amazon, and much lower on sites such as eBay and Taobao. Sellers can maintain relatively simple software development and IT operations geared to delivering product descriptions, images, and videos, since the marketplace provides the rest of the commerce platform. In many cases, sellers also receive fulfillment services that reduce the need for investment in a direct-to-consumer distribution network. A company based in Asia, for example, can gain access to millions of U.S. consumers through Amazon or eBay without having to hire a single employee in the United States.

Benefits to the Marketplace: Scale Driving More Scale—and Sophistication

Marketplaces are a rare example of having one’s cake and eating it, too. They profit both from the substantial commissions they earn on third-party sales and from selling their own inventory, often in direct competition with third-party vendors. By aggregating hundreds of thousands of sellers, they drive more traffic and provide all that choice to consumers. They spread the costs of generating demand over a broad range of goods and drive down fixed costs. They also keep customers on their sites longer. Between September 2007 and July 2012, Amazon more than doubled its number of unique visitors per month—from 42 million to 95 million. During the same period, annual sales tripled from $15 billion to $48 billion, distribution center efficiency increased by 36 percent (measured by sales per square foot), and spending on IT and customer service dropped from 5 percent to 3.7 percent of revenue. As visits and revenues increase, they provide an incentive for even more sellers to join, creating a virtuous cycle.

Increased volume has other benefits. Marketplaces gain improved negotiating leverage with downstream providers and access to an ever-greater amount of consumer information. They also can get a first look at high-performing sellers that are candidates for acquisition.

The range of choices offered by marketplaces, especially when combined with their superior understanding of consumers’ purchasing patterns, provides significant advantages over other retailers. One is the ability to customize offerings to microsegments of consumers. Further, with pricing algorithms that take into account tradeoffs between gross margin and commissions or levels of inventory, marketplaces can decide in real time whether to match or undercut the best prices proposed by other retailers on the marketplace.

What’s on the Horizon

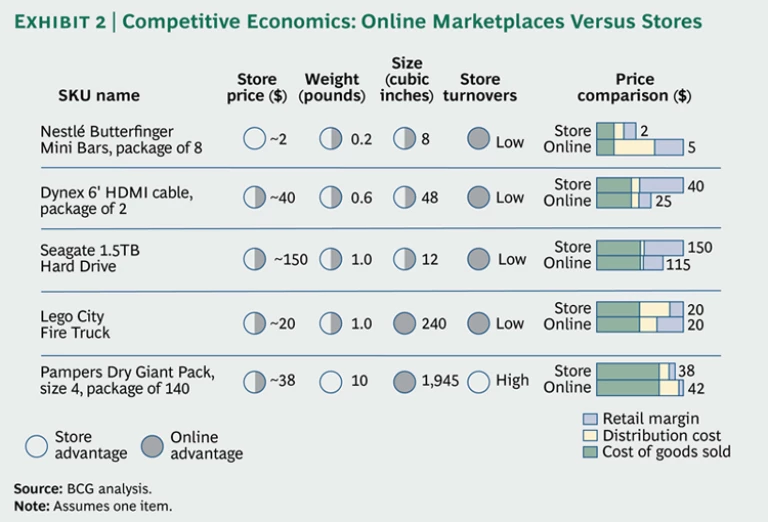

Despite their rapid rise, marketplaces have yet to take off in all categories. They have proved most effective for slower-moving lightweight products that cost $20 or more, where consumers value broad assortments and low prices. These include such categories as media, consumer electronics, and general merchandise (home office equipment, toys, and small appliances), in which the cost tradeoffs between distribution through stores (where retailers pay for rent and labor) and home delivery (where retailers pay for the cost of picking and packing and transportation) favor marketplaces. (See Exhibit 2.)

Other categories have been slower to move onto marketplaces. They include products that have:

- Tightly controlled distribution or high brand engagement, such as designer apparel and luxury goods

- High immediacy of need, such as over-the counter medicines

- Propensity for strong community interaction and specialized advice—baby and sporting goods, for example

- Low margins and are sold through heavily discounted closeout formats, such as discount apparel and dollar store items

- The need for temperature control—for example, produce, dairy, and frozen items

- Low price and high turnover, such as fast-moving dry groceries, where the cost of home delivery is prohibitively expensive and stores remain the most efficient distribution channel

Further change is coming, however, as several factors converge to bring some of these traditionally “safe” categories under attack. First, subscription programs such as Amazon’s Subscribe & Save, introduced in 2008, are expanding. Customers get free delivery and discounts of 5 to 10 percent when they sign up for recurring delivery on a monthly or quarterly basis. All parties benefit from such programs. Consumers avoid running out of things they use all the time. Marketplaces increase share of wallet and improve the predictability of logistics flows. Suppliers have an opportunity to increase frequency of usage and hence consumption, while locking consumers to their brands. Such programs could have a significant impact on categories like beauty, personal care, household cleaning, dry grocery, and waters and sodas.

The introduction of Add-on Items (launched by Amazon in May of 2012) allows users to aggregate low-price-point, nonperishable grocery products in a basket that’s economically viable to ship (with an aggregate value of more than $25). Historically, such items were available online only in bulk packs, which were mostly unattractive to consumers. Warehouse automation has brought down picking costs, and packing and shipping can now be amortized over the entire basket. “Click and collect” schemes, through which consumers order online and pick up at stores, dedicated facilities, or third-party locations, are also catching on. The advent of “fresh and frozen lockers” for perishable goods could continue to fuel the online migration of products.

Fight or Join?

In broad strategic terms, the choices facing retailers and suppliers are straightforward: join or collaborate with existing marketplaces, compete by creating one’s own marketplace or substantially expanded online presence, or try to maintain the status quo—an increasingly untenable option, in our view.

Challenges for Retailers. Joining a marketplace is more complicated than simply signing up. It requires building new capabilities in merchandising, marketing, CRM, promotions, supply chain management, and packaging. In merchandising, for example, the ability to determine the optimal product assortment for each channel (including managing overlapping SKUs in the store and online, as well as designating exclusive SKUs for the marketplace and products to withhold from the marketplace) becomes an important skill. So does setting prices for each channel, especially given the ability to adjust prices continually in the marketplace setting.

There are plenty of successful models to look to. Germany’s largest drugstore chain, dm-drogerie markt, for example, is pursuing a strategy of selling private-label products on Amazon, thereby leveraging Amazon’s core competencies in e-commerce and distribution, while continuing to operate some 1,250 brick-and-mortar stores.

For retailers, fighting—that is, creating one’s own marketplace—means expanding assortments, broadening offerings to consumers, building new capabilities, and deriving benefits of scale. It can be done only with a thorough analysis of the economics and a clear definition of the model. The former requires assessing potential sources of revenue—for example, advertising versus commission, or both; required marketing and infrastructure costs; and the costs of loyalty programs, among other factors. The latter involves determining the optimal user experience across platforms, whether other sellers complement or compete with one’s own inventory, and the best means of offering fulfillment services.

Issues for Suppliers. For consumer goods suppliers, joining a marketplace (or marketplaces) raises its own challenges with respect to channel management, particularly around pricing. In categories such as power tools, for example, marketplaces offer a fast-growing and profitable channel, but suppliers have to manage conflicts with large established brick-and-mortar retailers. Procter & Gamble has built a strong partnership with Amazon, with innovative promotions and new product formats (for example, in diapers) and packaging, allowing it to increase its market share significantly in the online world. Similarly, some apparel brands are opening boutiques on Amazon to improve control of how their brands are marketed and presented online.

For suppliers, fighting often means preventing the retailers carrying their brands from offering them on marketplaces. Adidas has recently announced that it would ban its dealers from listing its products on eBay and Amazon starting in January 2013. Issues of brand control versus potential revenue loss require careful weighing. If social networks are successful in building their own marketplaces, these issues will become even more complicated.

We believe that ignoring marketplaces is not a viable option. As the channel continues to gain prominence, suppliers will lose out either to direct competitors that decide to partner or to smaller companies that use marketplaces as a vehicle for growth. Or their assortment will end up on marketplaces anyway through third-party sellers—the worst of both worlds, since the suppliers will have forfeited their control of brand management.

Marketplaces will not be the last disruptive force to hit the consumer goods and retail industry. But for the foreseeable future, they will have an outsize impact in shaping profitable strategies for both retailers and suppliers. Those companies that figure out the best way to use this force to their advantage are most likely to prevail.