Florida Ice & Farm is a Costa Rica-based beverage company. From 2002 through 2008, under new CEO Ramón de Mendiola Sánchez, the company’s revenues more than quadrupled. In 2008, Mendiola went further, announcing that 40 percent of the variable portion of executive pay would now be tied to the company’s performance on environmental and social measures. He put in place a regime of strict measurements and strong managerial focus on environmental metrics, particularly solid waste, water use, and carbon dioxide emissions. The company developed ambitious targets to achieve zero net solid waste by 2011, and to become water neutral by 2012 and carbon neutral by 2017. One of its bottling plants became the most efficient in the world in terms of water usage. At the same time, the company’s revenues and market share continued to grow through a tough economy. Mendiola firmly believes that this commitment to sustainability is the only way to achieve continued growth and to sustain Florida’s position as one of the most influential and admired companies in Costa Rica.

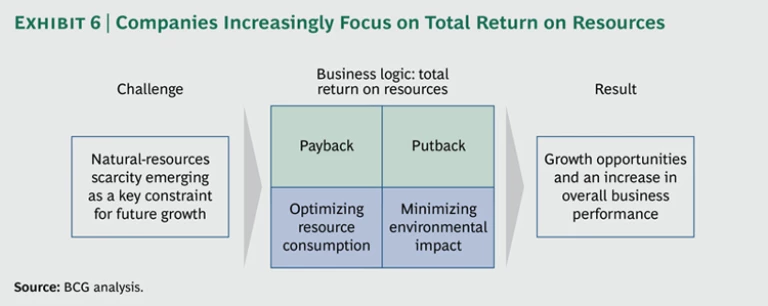

This is just one example among many of companies focusing on their “total return on resources.” These examples are part of a growing trend that has implications for all businesses. Continued population growth and development are straining natural resources and ecosystems that are vital to the worldwide economy. As old ways of production and distribution become more costly, companies will increasingly compete on the basis of a new paradigm: the efficient use of resources. They will monitor the payback from resources by optimizing consumption through the more efficient use of those resources. They will also manage the putback—that is, the effect of their actions on the future supply of natural resources and on the climate—in order to limit the damage.

In collaboration with the World Economic Forum, The Boston Consulting Group has identified 16 “new sustainability champions”—a group of emerging-market-based companies that are outperforming in terms of both financial results and their positive impact on society. We focus on five of these champions to explore what companies in both affluent and emerging countries can learn from them. Seven principles of resource management are crucial in creating competitive advantage. From these flow several simple steps that any company can take to improve its resource efficiency.

Resource Competition in a World of 8 Billion People

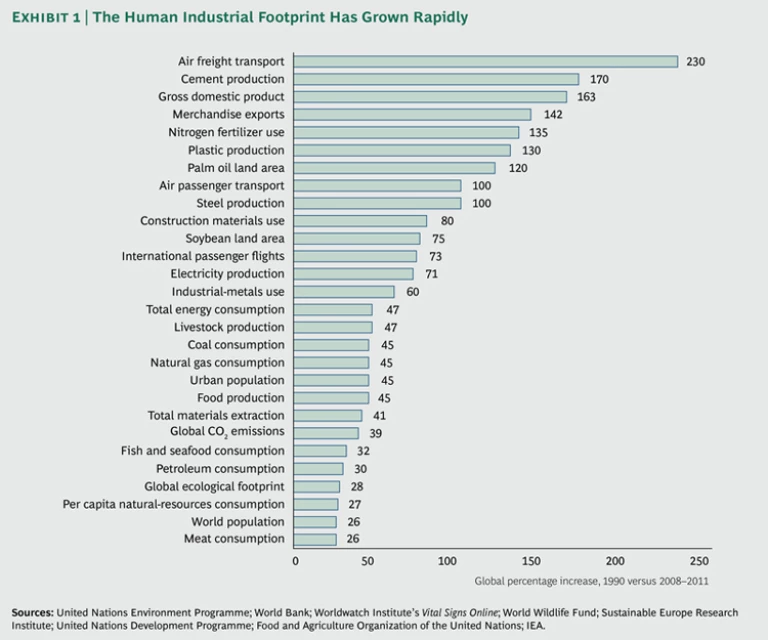

Companies are facing a new world of resource constraints. Humanity’s industrial footprint has greatly increased over the past two decades. (See Exhibit 1.) With rapid economic development in much of the world, global GDP is expected to rise from $69 trillion in 2008 (by purchasing power parity) to $135 trillion by 2030. The population will continue to grow, from 6.7 billion to 8.2 billion, in that same period. As a result, it will become increasingly challenging to meet demand for several vital minerals and metals, as well as for oil and water.

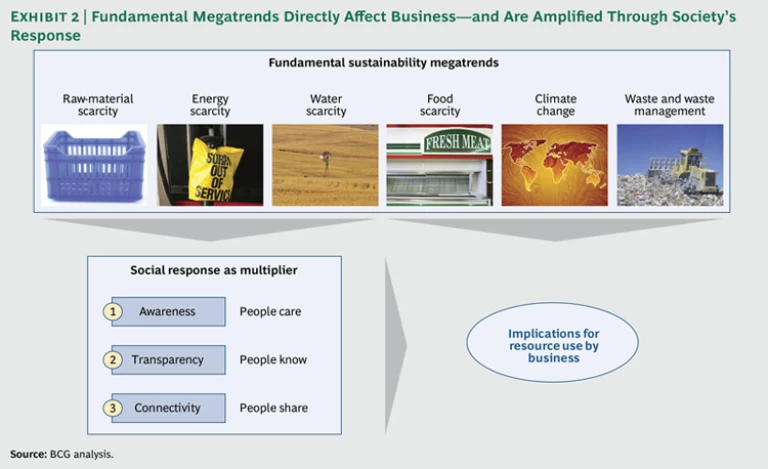

Six sustainability megatrends are particularly pertinent for businesses and are amplified by society’s response. (See Exhibit 2.) Taken together, they represent a real call to arms for all companies in terms of addressing resource management. The decline of readily available supplies will increase competition and price volatility for four key factors of production: raw materials, energy, water, and food. At the same time, companies will need to become more aware of their generation of emissions and waste—especially if they pose health or pollution risks.

Globalization has improved access to many resources, and human ingenuity continues to discover new sources and improved methods of extraction and distribution. But easily extractable, high-grade supplies are dwindling faster than new ones can be found. Few if any resources will actually run out, but companies will need to change their thinking as we go from a world of abundance to one of limits.

As vital raw materials become harder to obtain, companies will face new roadblocks in their operations. These challenges range from higher and more volatile prices to social protest and unrest over the use of these resources as the public’s tolerance for pollution declines.

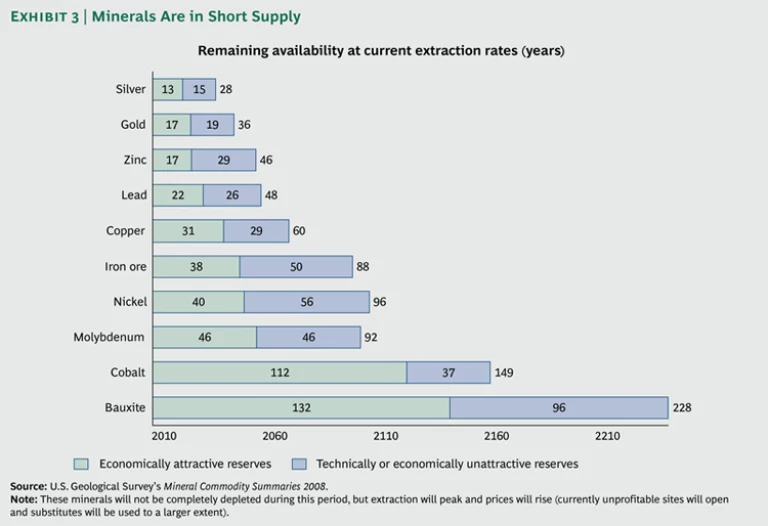

Many commonly used materials have relatively limited known reserves. For example, silver, gold, zinc, and lead may no longer be available 30 years from now—except through recycling—if significant new stocks are not discovered or made economically viable. (See Exhibit 3.)

Declining stocks inevitably lead to higher and more volatile prices, which have an immediate impact on operations and profitability. The prices of many raw materials have peaked recently, triggered by a number of factors, including an increase in demand from emerging countries—particularly Asia. Peak prices are bringing new supplies on the market, but these are usually lower-grade or hard-to-produce supplies that are useful only at high price points. Volatility, high prices, and competition for stocks will become the norm for an increasing number of raw materials.

A similar logic applies to energy sources, such as fossil fuels—especially oil. Prices have risen from $25 to $100 a barrel in the past decade, mainly as a result of two factors. The first is again the large increase in demand from emerging countries. The second is a drop in conventional supplies as we exhaust the easily accessible deposits. Although new supplies have been discovered, these are often more expensive to refine and bring to market. The world is unlikely to run out of oil in the near term, but prices will probably continue to be volatile and gradually go higher. As for natural gas and coal, there are abundant global supplies, but most of the available natural gas requires “fracking” processes that pose environmental risks, while coal is a major contributor to air pollution.

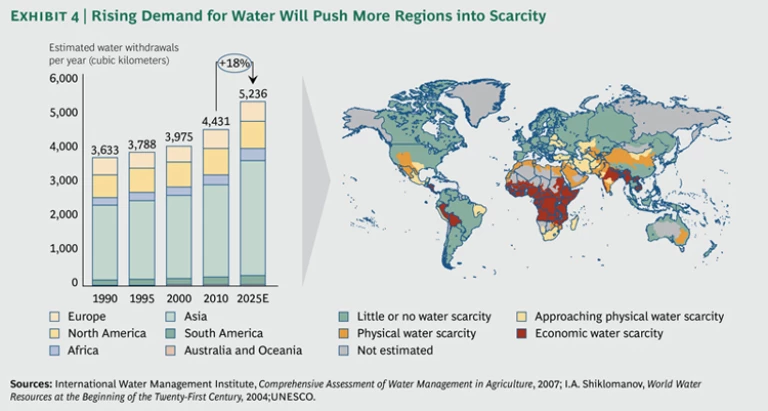

Water is often taken for granted, but freshwater supplies are also tightening in many parts of the world. There are multiple reasons for this, but rising affluence is a key driver. Many new middle-class consumers, for example, are replacing grain in their diet with meat, which requires far more water to produce. (See Exhibit 4.)

Economic development and population growth are also affecting the stability of the climate. Rising carbon emissions have led to increasingly variable weather in recent years, and annual emissions are likely to grow by a third over the next 20 years. Long before the polar icecaps melt, companies will suffer from a greater frequency of severe weather events. CO2 emissions may well reach 40 gigatons in 2030, a good deal higher than widely accepted norms of stability. Future weather changes could be catastrophic: melting shelf ice could raise global sea levels by 20 feet, devastating coastal areas worldwide. Heat waves will be more frequent and more intense. This will ultimately affect all businesses in all parts of the world in one way or another.

Whether companies themselves face shortages in resources, or governments and social pressures force the issue on them, these challenges will be a corporate priority in the coming years. As we move to a world where resources become a more prominent part of management’s agenda, what should companies do?

Putting Resource Management at the Core: Total Return on Resources

To succeed in this new world, companies will need to put resource management at the core of their business.

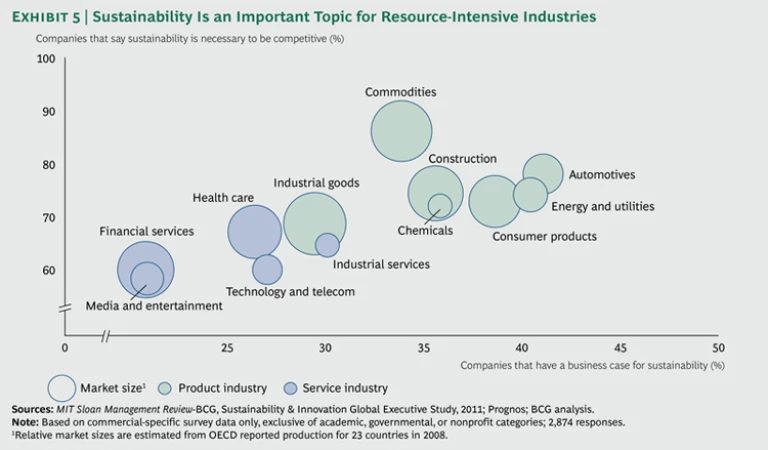

To understand what that means, we can turn to companies that already face resource constraints. In BCG’s annual survey of executives across the globe, cosponsored with the MIT Sloan Management Review, we saw that resource-intensive industries treat sustainability as a core issue. They view resource management as a necessary part of their competitiveness, and many of these companies have a business case to support and drive their actions. (See Exhibit 5.) Each year, they put more emphasis on sustainability issues as resource challenges become more pressing.

Constrained resources will increasingly force companies to take two governing metrics into consideration. They will have to monitor the payback from natural resources in order to minimize the consumption of scarce supplies. Electric utilities, for example, invest heavily in improving the efficiency of their generating plants to reduce how much fossil fuel they need in order to produce each megawatt. Companies will also have to watch their putback of natural resources in order to minimize their damage to the larger ecosystem. Electric utilities are investing in scrubbers and other processes to reduce the harmful emissions they release into the atmosphere. (See Exhibit 6.)

This attention to the “total return on resources” changes how companies grow and compete with each other. But this is not a new story: companies have always optimized their inputs and outputs to maximize profits. The inputs that are the most constrained get the most attention. The industrial revolution made natural resources a competitive factor in the nineteenth century, as companies located operations near hydropower and other low-cost energy sources. Energy became relatively abundant by the twentieth century, so executives turned their attention back to labor costs by, for instance, implementing automation. Or they focused on new sources of advantage—such as quality, speed, and other attributes.

As competition for resources increases, resource management will rise to the top of the company agenda once again. Companies that excel within this new paradigm of competitive advantage will turn this constraint into an opportunity and gain market share. Those that fail to respond to this trend will suffer from price increases and volatility, regulation, and social pressures.

Welcome to the new world of sustainability. As resource supplies fail to keep up with burgeoning demand, companies will start treating sustainability as a central part of management rather than relegate it to a vaguely defined office of social responsibility. The world as a whole is on the verge of a new wave of innovation in resource management. And as with all innovation, this will create opportunities for companies that can help their customers address these concerns.

Resource management will also help to solve the problem of responsibility. In the past, each producer used resources inefficiently and let the wider society worry about the consequences. Now companies will be motivated to make improvements themselves. Resource scarcity is already frequently a factor in the developing world. Despite the common presumption that a focus on sustainability is a luxury for the developed world only, many companies in emerging economies are, in fact, already finding smart ways to anticipate the changes and create competitive advantages. These leaders can teach other companies, in the developed as well as the developing world, how to thrive in a resource-constrained world.

Understanding What Leading Companies Do

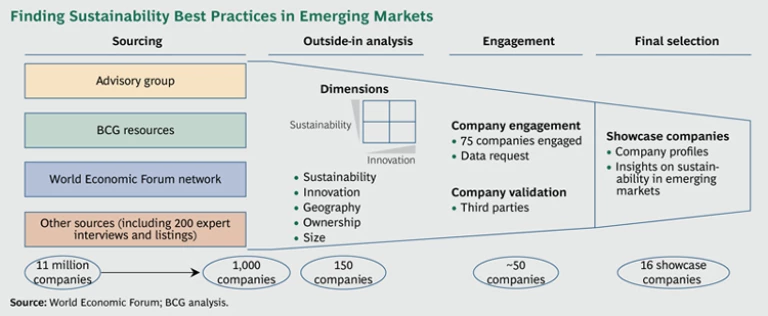

For the past two years, the World Economic Forum and The Boston Consulting Group have worked together to find sustainability leaders in the developing world. After researching thousands of companies, we focused on 16 that have managed resources wisely while achieving profitable growth. (See Exhibit 7. For more on this project and the methodology used, see the Appendix.)

These “new sustainability champions” have identified opportunities and innovations that companies based in affluent nations often seem to overlook. They provide inspiring examples for companies everywhere that are looking to tackle today’s challenges of performance, innovation, growth, and sustainability. The success of the new sustainability champions stems from three primary practices.

First, they turn constraints into opportunities through innovation. They have a pragmatic approach, adapting and tailoring existing technologies to their local business environment. They look for alternative ways to bring products to market, or to develop markets that have not yet taken off.

Second, the champions embed sustainability in their company culture. They know that only with the commitment of the entire organization can they combine sustainability with profitable growth. All employees are involved in defining and delivering on common goals and ambitions that maintain a sustainability focus.

Finally, they actively shape their business environment. The new sustainability champions acknowledge that everyone along their value chain—from suppliers to customers—does not necessarily embrace or understand their views and goals. They educate suppliers, customers, and others to shape the environment in their favor. When they see government policy regarding their industry functioning poorly or against their interests, they may reach out to influence policymakers.

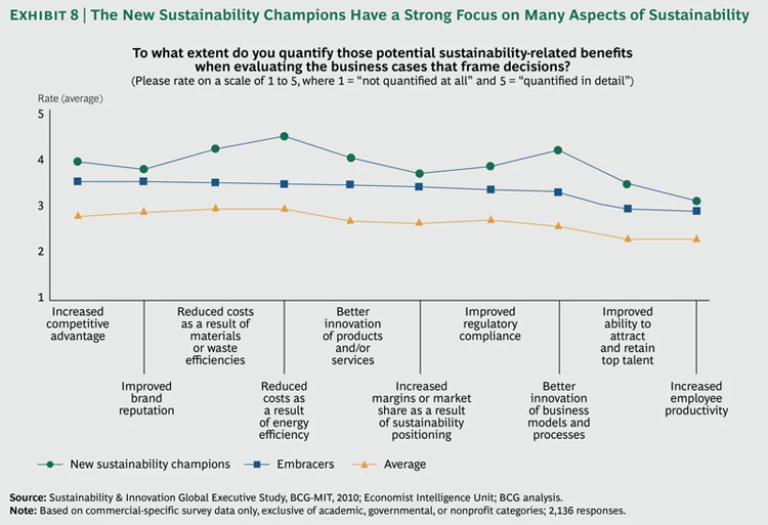

Indeed, they are outliers when compared with the “embracers” of sustainability, as identified by the BCG-MIT Sloan Management Review collaboration of 2011. Embracers are companies that say sustainability is necessary for profitability, have it permanently on their management agenda, and have made a business case for sustainability. Compared with them, the champions have a more holistic outlook, including a wide variety of environmental and social elements in their thinking. They push multiple boundaries at the same time but with one clear focus and business logic. They are better at measuring the benefits of their efforts—not just in terms of quantifiable targets, such as energy efficiency, but also in terms of intangibles such as corporate reputation and attractiveness to talent. (See Exhibit 8.) They also seem to incorporate the risks of resource shortages more deliberately into their business decisions than the embracers do.

What is most striking about the new sustainability champions is their motivation. Government regulations and competitors, the main drivers for many companies, matter less to them; they work largely from internal motivations. As befits leaders, they manage their context and are pushed from the inside to move aggressively.

To understand these outliers better, we selected five companies for a deeper analysis into how they brought about their success. They work in different industries and in different regions, and they therefore face distinct types of constraints. Yet they all share one characteristic: resource management is a core element of their business logic. By conventional measures, the success of these champions shows that efficient resource management can come together with above-average profitability and growth. They challenge the assumption that there is a tradeoff, which deters many would-be champions. Far from holding them back, their focus on sustainability has spurred new opportunities and growth. This fits the findings of other researchers, who have found that companies with a focus on sustainability tend to outperform their peers.

China’s Broad Group, Kenya’s Equity Bank, India’s Jain Irrigation Systems, India’s Shree Cement, and Costa Rica’s Florida Ice & Farm exemplify different aspects of resource management. Jain and the Broad Group work directly to help customers use natural resources more efficiently. Equity Bank works indirectly, enabling many of its customers to produce more without using up scarce topsoil. The products of Shree Cement and Florida Ice contribute little to resource management, but the companies have made enormous progress in improving the efficiency of their own resource-intensive production processes. Together, these sustainability champions illustrate the many ways that companies can move forward on this major issue. (For more on all 16 companies, see Redefining the Future of Growth: The New Sustainability Champions , BCG-World Economic Forum report, September 2011.)

China: Broad Group

The Broad Group has recently become well known because of its rapid construction of high-rise buildings, but it is also one of the largest manufacturers of air conditioners in the world. This is an example of an industry that would normally raise environmental concerns. As China rapidly industrializes, its burgeoning middle class is insisting on the same conveniences that people in the developed world enjoy—with the same heavy reliance on fossil fuels and resulting release of CO2. China is already a major contributor to emissions because most of its electricity comes from coal, and it has some of the most polluted cities in the world.

Broad, however, relies on alternative technologies to reduce its draw on resources. To move beyond conventional electric units, it perfected air conditioners that run on natural gas. Gas burners heat a special lithium-bromide solution to the boiling point. As the lithium bromide vapors condense, they create a cooling effect that draws heat out of the system. These “chillers” are twice as efficient as conventional electric air conditioners, mostly because they get energy directly from the fuel source rather than through a middle step of producing electricity. While less convenient in some cases than electric units, because of the need to connect to a natural gas or other fuel source, they can achieve impressive savings in fuel use and emissions. The units do even better when connected to a waste heat source, such as in a power plant or a factory with almost zero CO2 emission.

A privately held company, Broad had $600 million in revenues in 2010 and provided the majority of energy-efficient air conditioners in China. It also exports to 70 countries. From its success with air conditioning units, it has branched out to indoor air-filter systems and prefabricated sustainable construction modules that make use of 15-centimeter thermal insulation and four-pane windows. Its goal is to combine sustainable development with human development, so people in China and elsewhere can enjoy material comforts while respecting the new limits on natural resources.

Kenya: Equity Bank

Equity Bank, by contrast, achieves its efficiencies indirectly. Farmers in Kenya have long relied on subpar agricultural methods that deplete their key natural resource: the soil. With access to outside financing, they can be convinced to invest in expensive fertilizers and other improvements that would increase yield as well as improve the soil. Without that access, farming in many areas is likely to decline.

Most farmers, however, live in remote areas where it is impractical to locate physical bank branches. Equity pioneered a mobile banking system in conjunction with Safaricom, a large East African telecom provider. It then launched “agency banking,” with village shopkeepers working as agents for the bank and farmers able to make transactions through mobile phones and receive cash and credit from the shops. Over time, Equity has improved its offerings to support farmers with loans through all stages of agricultural production and distribution. It has even worked with partners to train farmers in financial management.

While giving farmers the opportunity to invest in the soil and therefore farm more sustainably, the bank has greatly expanded its customer base and grown rapidly. In 15 years, the percentage of the Kenyan population participating in the banking system has increased from 6 to 35 percent. With 7.5 million customers, $350 million in revenues, and a capitalization of $1.2 billion in 2011, Equity has become the largest bank in Kenya and the biggest African-majority-owned company in the region. It has expanded to neighboring countries with similar agricultural challenges, while maintaining strong profit margins. Rival banks have since adopted many of these innovations, extending the reach of mobile banking to more farmers.

India: Jain Irrigation Systems

Jain Irrigation Systems of India addresses another scarce agricultural resource. Most Indian farmers rely on flood irrigation, a legacy of the country’s once-abundant freshwater reserves. India’s rapidly expanding population has led to water scarcity in some regions, yet many farmers continue to tax supplies with traditional methods. Drip-based irrigation systems are available, but only large farms have had the money and the expertise to install them.

In response, Jain imported and adapted a drip system specifically meant for smallholders. This modified system achieves nearly the same effectiveness as conventional systems but can cut water usage by more than half. That’s partly because Jain complements the technology with education on “precision farming”—optimizing the balance of fertilizers and pesticides as well as water. Farmers find that drip systems can actually increase their yields. But even with the modifications, many farmers have trouble paying. So Jain set up a buying organization that guarantees farmers a minimum price for their crops. As a result, banks are much more willing to grant loans to Jain’s customers.

Eager to reach this still largely untapped market, the company sends its employees far into the countryside to spread the word about the new irrigation systems. That includes staging dancing and singing shows at local festivals to reach illiterate farmers. Jain’s creative marketing has paid off with rapid growth and solid profitability for the privately held company.

The company had $740 million in revenues in 2011 and is aggressively expanding outside India into sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere. Its researchers are also working with counterparts in Israel and the United States to continue to improve the technology of water-conserving irrigation.

Costa Rica: Florida Ice & Farm

Costa Rica’s Florida Ice & Farm has been ahead of the curve in managing its use of natural resources. As a beverage company, it is most concerned about the availability of clean water. The country still has ample supplies, but urbanization is threatening the quality of its aquifers. In 2008, Florida Ice began to focus on the issue and, in the process, has managed to drastically improve its water efficiency—going from 12.2 liters for each liter of beverage produced to only 4.8 liters in 2011, one of the lowest rates in the world. It continues the effort by targeting an ambitious level of 3.5 liters of water per liter of beverage.

The company is now close to achieving its bold goal of becoming water-neutral. To make up for water consumed in the factory, it provides clean water to local communities and pays landowners to protect watersheds. The company also aims at waste- and carbon-neutrality, taking a big step forward by building a recycling plant that receives containers from competitors as well as from its own factories. It has been able to receive and recycle more than 99 percent of its industrial solid waste.

While these changes were not a response to actual shortages, the company’s leaders are convinced that they have taken vital steps to prepare for the future. In order to motivate employees to meet its “triple bottom line,” the company links 20 percent of executives’ variable pay to social goals, 20 percent to environmental goals, and the remaining 60 percent to financial goals.

While investing in sustainability, Florida Ice’s overall rates of growth and profitability since 2008 have been well above the average for its market, and the company has been able to acquire a series of smaller companies. Its operating income grew at a compound annual growth rate of 6 percent from 2008 through 2011 to a total of $140 million.

India: Shree Cement

Cement might seem an unlikely industry in which to find a sustainability champion. India’s Shree Cement, however, has established itself as one of the most environmentally conscious companies in its industry, focusing on reducing both energy use and waste. Shree Cement identifies sustainability as the only way forward and recognizes resource conservation as one of the main strategies for attaining complete environmental sustainability.

Shree Cement was the first cement company in the world to be certified EN 16001—the international energy-management standard—in recognition of its ability to continuously monitor and document energy use, identify action targets, and develop a pathway for reducing specific energy consumption. Shree also finds clever ways to reuse waste products—such as slag and fly ash—as materials in its production processes.

The company has made a number of large capital investments to conserve resources, all of which have delayed payback. For gypsum, a key ingredient whose supplies are under pressure, the company developed a process for synthesizing the material from byproducts of its 300 megawatt coal-fired power plant. That same plant also has the country’s largest air-cooled condenser, which replaced a water-cooled process and greatly reduced the consumption of water. On top of that, Shree added a 46 megawatt “green” power plant that runs on waste heat from production processes.

Shree also invests in its workforce, which helps it achieve a high retention rate as well as a strike-free workplace. It spent $1.9 million on betterment projects for local communities. All of these efforts have coincided with rapid growth, with revenues increasing by almost 50 percent per year from 2005 to 2009. Shree Cement is today one of the five largest cement manufacturers in India, with 2012 revenues at $1.06 billion and a stable EBITDA margin of 32 percent.

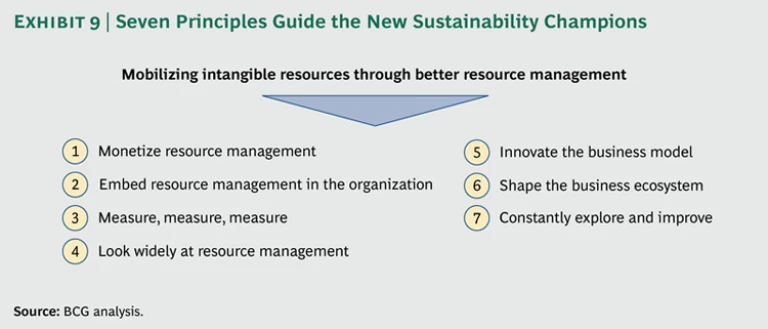

The Seven Principles of Total Return on Resources

What are the key elements of an internally driven focus on sustainability and growth? Through a series of interviews and deep-dive analyses, we have distilled seven core principles that guide the new sustainability champions’ focus on total return on resources. (See Exhibit 9.) These principles may seem familiar management dictates for any major initiative, yet they take on special significance in the context of resource management.

Monetize Resource Management

Even in emerging economies, resource management can take on the aura of a feel-good initiative designed to please stakeholders. If employees see it this way, they will never integrate it into core activities and planning. Instead, the organization has to adopt resource management as a strategic differentiator that will drive growth and profitability. People have to believe that they can monetize it.

Monetizing can work by increasing resource efficiency along the existing value chain and adding new products that improve resource management either internally or for suppliers or customers. The monetary gains have to exceed the costs within a manageable time horizon, and these gains must accrue to the company itself, not just to the industry or the wider society.

Shree Cement is explicit about optimizing cost as part of its commitment to sustainability. The company is constantly scrutinizing its operations to identify process or material innovations that could reduce costs. For example, in 2011, Shree estimated that it generated savings amounting to 8 percent of its aftertax profits for that year through measures such as installing rotary screens on fly ash silos and increasing direct deliveries to customers to reduce the use of secondary freight.

Embed Resource Management

Exhorting employees to monetize sustainability is not enough. Companies also need to embed the key concepts of resource management within the organization. They must go beyond strategy and into corporate structure, governance, and the organization’s mission.

Focusing on resource management will be a major shift for many organizations and therefore may require some persuasion. Industry leaders will have few immediate tangible benefits to offer, especially for resources that have experienced only mild pricing pressures. They will need the vision and understanding to communicate the growing importance of total return on resources. Only then will the organization be ready to embrace projects with uncertain outcomes—and to adapt when roadblocks emerge. Resource management can’t have a project-of-the-month strategy; it has to be accepted as a standard part of how the company works.

Some organizations already have a culture built around sustainability. Jain Irrigation was started by an entrepreneur from an Indian village that was suffering from water shortages. He saw farmers sinking into terrible poverty, with many forced to let their farms fall into disrepair or to abandon their fields and move to the city. That motivated him to create a business around making agriculture sustainable through drip irrigation. This single-minded goal pervaded the organization as it grew, and the founder’s son continued to spread the word to employees when he took over.

Most organizations may not make a moral commitment to resource management the way Jain Irrigation has. But there is no reason they can’t appeal to higher motives. Equity Bank had no special commitment when it looked into the problem of reaching remote villages. But it soon realized that small farmers would never become substantial customers until they improved their productivity. And the bank would never be able to finance those improvements unless it could deliver services without physical branches. Those realizations led the bank’s executives to adopt sustainability as a deep-seated organizational value, one with the important side benefit of motivating employees who wanted their work to be more than just a job. Those motivated employees, in turn, not only figured out how to make mobile banking profitable sooner than board skeptics assumed but also how to reduce resource use in other areas. Their enthusiasm helped speed up Equity’s transition to paperless banking.

The Broad Group takes an even more holistic approach to embedding a culture of sustainability. Most of its operations take place on a “green campus” with energy-efficient buildings. Employees eat in a cafeteria supplied by the company’s own organic farm. They see examples of effective resource management all around them.

Measure, Measure, Measure

While some industries have managed their resources for decades, most are only now starting to make the effort. They are often still in the exploratory stages, when it is tempting to set vague goals and just learn along the way. But as executives realized long ago, what gets measured gets managed—and everything else falls off the radar when people get busy. Measurement is fundamental for the companies we researched, and they measure relentlessly.

As soon as the organization has developed objectives or projects, it can define and communicate a set of indicators that show progress. These must be concrete and quantifiable enough so that managers can track results. Some initiatives will fail, while others will succeed faster than expected. The sooner the company can shift investments from one to the other, the more it will accomplish.

Transparency is essential here, not just for the layers of management but also for the full organization. The best way to demonstrate the importance of an initiative is to broadcast the metrics and post frequent updates—and to celebrate milestones. And while the company must demonstrate the seriousness of these measures, executives should also be ready to adjust them as the projects and their environments evolve.

Partly for those reasons, it is better to go with a few, easily understood “magic metrics” than with an exhaustive list of all the indicators around a process. Magic metrics can act as symbols of commitment and, hence, galvanize the organization and drive cultural change while giving the company something manageable to focus on.

Florida Ice adopted a limited number of indicators as part of its effort to produce no solid waste and to be water neutral and eventually carbon neutral. It installed permanent monitoring of these resources, and it now reports progress regularly to the broader organization. A single scorecard for sustainability, bringing all the metrics together, allows employees to see in a snapshot how the company is doing. The company combines metrics with education, and its employees have gotten caught up in the drive for improvement. More than 95 percent have gone on to volunteer on company-sponsored projects to restore local watersheds, educate consumers, and support suppliers and customers working to reduce their environmental footprints.

Look Widely at Resource Management

Most companies tend to focus on the direct financial benefits of resource management. The best companies, however, have a much broader sense of the concept. They take a holistic perspective on their resource use, looking at all inputs and outputs.

Consider again Florida Ice, which could have been content to make its factories highly efficient in their consumption of water. Instead, the company also focused on the sustainability of local water supplies as a whole. So its factories worked with local communities to preserve the watershed that served everyone. In 2011, the company invested 7.1 percent of aftertax profits in environmental and social projects in alliance with local NGOs and community leaders.

This holistic approach can go a long way to reducing operational risks for a company. By working broadly with stakeholders, companies can promote better management of the resources they depend on. When companies are able to identify their operational risks and better mitigate and prevent them, they create competitive advantages. Shree began using a “scavenging” approach when it adapted its kiln to act as an incinerator. It disposed of solid waste from local communities while reducing its fuel bill.

Be Innovative with the Business Model

Resource leaders will work to be innovative with the overall business model, not just to make changes within it. Just like products, business models have a limited lifespan and must evolve over time. The change can be as ambitious as a new value proposition for the main business. Or it can yield a complementary offering that strengthens the main one.

Jain started with irrigation units but eventually realized its growth would be limited as long as farmers couldn’t qualify for bank loans. One way farmers could qualify was to get sales contracts with commodities dealers. Finding no such dealers in many of its markets, Jain branched out into commodities wholesaling. As the company gained expertise, it was able to guarantee minimum prices for its customers, which in turn encouraged banks to lend to them.

This type of innovation often requires investments in research and development, either to bring out entirely new products or to adapt technology from elsewhere. The Broad Group wasn’t content with improving the energy conservation of their air conditioners. The need to improve building insulation was everywhere. So it retrofitted nearly a dozen of its buildings by incorporating thick thermal insulation and four-paned windows.

Shape the Business Ecosystem

While they focus on improving their own operations, leaders in resource management will also want to look over their entire value chain. That means going beyond their own or their customers’ resource demands, as Jain and Broad have done from the start, and addressing the demands of suppliers and distributors, too.

In this way, companies can go beyond merely communicating priorities to suppliers or teaching customers about the efficient use of their products. Choices they make about product specifications can determine how the constituent materials get made or shipped. Smart companies will consider the full ramifications of these decisions. As long as the company monetizes the benefits, it may make sense to sacrifice some efficiency internally in order to reduce resource consumption elsewhere in the value chain.

Companies will even look to change mindsets in the society at large. The Broad Group applies its metrics to the public by measuring levels of air pollution in target communities. People who see regular reminders of pollution levels will be more inclined to buy a gas-powered air conditioner that won’t draw on coal-burning generating plants.

Going a step further, leading companies can gain a powerful competitive advantage by setting standards that most or all players in the category will have to follow. By partnering with or lobbying regulators, these pioneers can persuade governments to turn their practices into the regulatory standard. Even when governments aren’t involved, market leaders can convince suppliers and customers of the need to support those practices as industry norms—norms that match the company’s strengths. Rival companies will have to catch up or even reconfigure their own practices in order to meet the standard, giving the pioneer an advantage for years to come.

Equity Bank gained this edge when it innovated in mobile banking in Kenya. The government didn’t set standards, and other banks quickly jumped in. But Equity’s approach proved so popular that the new entrants had to imitate its agency structure and its interface with Safaricom’s technology, rather than adopt an approach customized for their own capabilities. They have yet to match Equity’s success.

Florida Ice was a model of effective lobbying when it worked with regulators. The government had initially implemented penalty-based rules on resource usage that threatened to add substantial costs as the company grew. Instead, Florida Ice persuaded regulators to move toward a positive system that offered credits for reductions in resource use in any part of a company’s business. That means that Florida Ice now gets full credit for the water conservation it promotes in communities beyond its plants.

Florida Ice also freely shares its practices with rivals. While that might not be advisable in every industry, it makes sense here because, as the market leader, Florida Ice is also trying to raise the reputation of the industry as a whole. That is important at a time when beer and soda bottlers are under attack for contributing to excessive alcohol consumption and obesity. This sharing also helps to ensure that Florida’s approach will guide the industry’s development as a whole.

Constantly Explore and Improve

Finally, as more companies recognize the growing resource constraints, pioneers in resource management will have to keep moving. Their advantages will be temporary, so they will need to improve relentlessly in order to maintain an edge. They will want to readjust their targets on an ongoing basis—using those metrics that they have already invested in and finding new relevant ones to stay ahead of the curve.

Business intelligence is vital here—not just to know where the company stands with its rivals but also to see if others have had success with processes or materials that are under consideration. Looking out to the wider world is helpful also in setting benchmarks and grasping what is possible, after factoring in the different conditions at hand.

Even if rivals haven’t caught up, organizations will benefit from raising their expectations at frequent intervals. That way, employees can continue to feel the energy and satisfaction of reaching new peaks and avoid the complacency that comes from success.

To drive constant improvements in its operations, Florida Ice has relied heavily on its widely publicized goals to be water, waste, and carbon neutral. Pressure from those ambitious objectives drove its managers to look broadly for models to imitate and benchmarks to set. But in some areas the company is already doing so well that it has to work on its own. In 2007, it bought a local bottling plant that was already quite efficient. Two years later, Florida Ice had fine-tuned it so that it has now become the most water efficient in the world, requiring only 2.3 liters per liter of finished product.

The Broad Group focuses more on individual improvement. It starts with extensive employee training and development. As people advance professionally, they can accomplish more and reach higher targets. Constant improvement on the individual level helps the company push for gains on the company level.

A Call to Action

Changes in resource availability will drive new competitive dynamics, and the capabilities that lead to success will correspondingly change. This is not a niche issue that touches only a few companies but rather a universal phenomenon that applies to all. Like the new sustainability champions, which already understand how to operate in this altered world of scarce resources, future market leaders will focus on resource management as a pathway to growth. By putting resource management at the very core of business strategy and operations, these companies will be able to leverage the opportunities that lie behind what appear to be constraints.

Managing with scarce resources may seem to require enormous effort. But companies don’t need to become best in class to reap the benefits of better resource management. Instead they can work their way up gradually, starting with the basics, as follows:

- Understand the current resource situation. Companies should start by assessing their current resource situation through sound resource-oriented accounting and measurement, or by leveraging frameworks such as the nonprofit Global Reporting Initiative, which provides help with sustainability issues. To complete the picture, they will need to consider the entire value chain. Academia, nongovernmental organizations, and competitors can be helpful here. Next, companies can identify their key resource constraints, benchmarking themselves against leading organizations both within and beyond their industry, to identify the most critical inputs and outputs. Finally, they should lay out their own goals, focusing on the biggest risks and opportunities.

- Develop solutions. Companies need to find new opportunities and innovations that break the usual tradeoffs between growth and conservation, looking beyond their own boundaries to the greater sphere of influence. It is essential to prioritize projects in the implementation. Simple frameworks that rank projects on impact versus effort can help.

- Implement. Successful implementation requires that companies ensure leadership commitment. Senior executives must be seen embracing projects based on total return on resources; delegation is not an option. Next, frame the opportunity, not just the cost of the project. And as implementation begins, measure relentlessly to maintain focus and also to quantify and celebrate progress. Finally, improve and explore continually, as the competitive environment and society are changing rapidly and creating new threats and new opportunities.

Appendix: Project Description and Methodology

The World Economic Forum and The Boston Consulting Group partnered to research and understand the most effective innovation practices for driving sustainable growth in emerging markets.

The research covered all emerging regions and industry sectors. It began with the compilation of a list of more than 1,000 emerging-market-based companies with annual sales ranging from $25 million to $5 billion. The study involved detailed reviews of these companies, coupled with interviews of almost 200 business executives. The list of 1,000 was drawn from the experience and knowledge of those in the World Economic Forum’s network, from the array of companies with which BCG has worked, from interviews with experts, from publicly available listings, and from the expertise of the study’s project advisory group.

After gauging the companies in light of criteria such as sustainability, innovation, and scalability, we filtered out a shortlist of 150. Further analysis—including additional interviews with experts—yielded a penultimate list of about 50 companies. A final round of investigation, in most cases involving interviews with the CEOs and chairpersons of those remaining organizations, led to the selection of those we call the new sustainability champions. (See the exhibit below.)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the other members of the BCG steering committee that helped with this report, including Tenbite Ermias, Rahul Jain, and Bernd Waltermann.

They would also like to acknowledge the substantive effort of BCG’s Strategy and Global Advantage practices, as well as the following BCG contributors: Carola Diepenhorst, Charles Gardet, and Anja Gottschalk-Wenk.

Furthermore, they would like to thank John Landry for his assistance with the writing of this report as well as Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Sarah Davis, Angela Di Battista, Abigail Garland, and Anna Tustison for their help with editing, production, and design.