In challenging economic times, smart use of pricing techniques can be one of the most direct and least expensive tactics that retailers can deploy to spur immediate performance improvements. Appropriate pricing boosts not only top-line sales revenues but also store traffic, brand perception, purchase frequency, and customer loyalty. And it delivers results much faster than most other revenue-enhancement changes.

It’s not easy to sync the many complex elements of a pricing strategy. But retailers that manage to do so often reap substantial rewards. We believe that companies undergoing a top-to-bottom realignment of strategies, tactics, and processes can turn pricing into growth opportunities and competitive advantage—as well as spur annual EBIT margin improvements of 2 to 5 percent of sales. Through our work with a wide range of companies, we have found that top performers with holistic pricing strategies often realize the greatest benefits, although potential profits are available to any company.

Poor retail pricing decisions, however, can chase away customers and drive a business into the ground. Sometimes companies discount or heavily promote their products to turn around falling foot traffic yet fail to produce the desired boost in basket size or margins. Other times, they make sweeping, highly public changes in their pricing strategies but neglect to fully test the concepts with consumers, causing the initiatives to flop.

Why do companies allow this to happen? The reason: Pricing decisions are too often made by gut instinct, based on incomplete or wrong information, or executed without proper planning and follow-through. To make better pricing decisions, companies must overcome three key challenges.

- A Reliance on Unsophisticated Pricing Approaches. Some businesses respond too aggressively to competitive pricing moves, often hurting their own profits. Others directly pass along a cost increase to consumers to maintain their margins in key categories. Consider fluctuating commodity prices, for example. In the process, they ignore more sophisticated approaches that capture much greater profits.

- Organizational Barriers. Success can be elusive when many people and functions are involved in pricing but no one person holds a systematic, integrated view of the strategy overall. Poor decisions also result when senior management does not pay enough attention to pricing.

- Inadequate Systems and Tools. Often pricing is not regularly tracked, analyzed, and managed. Most retailers have plenty of data, but inadequacies in IT and analytics often thwart effective segmentation and dynamic pricing strategies.

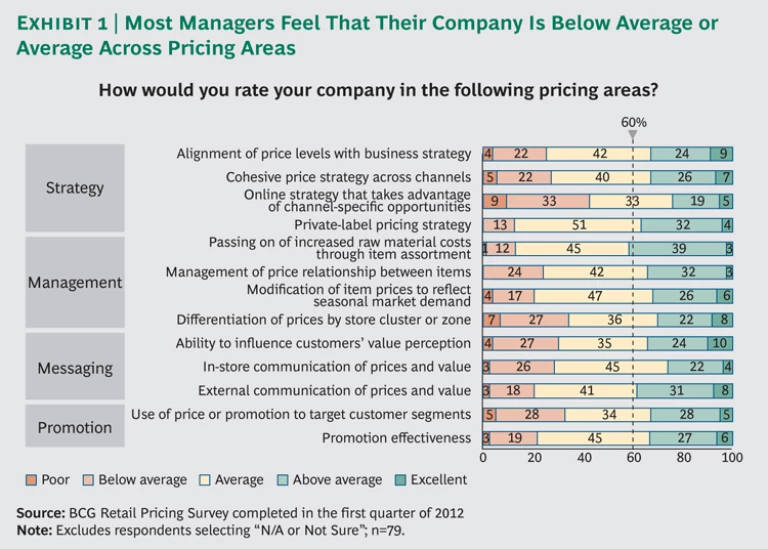

We discerned many of these issues in a BCG survey of approximately 80 senior retail executives at global companies. The organizations were mostly headquartered in North America, but Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa were also represented.

Fifty-three percent of respondents believed that pricing should be one of their top two priorities, but only about 38 percent felt that their company currently prioritized pricing that way. Most reported that their company’s pricing strategy generated significant short-term value, but fewer than a third of respondents felt that their pricing approach was a competitive advantage for the company. And though 91 percent of executives said that the complexity of pricing had increased over the past decade, 34 percent of retailers reported that they did not have dedicated pricing teams to help manage that complexity.

Basically, retail executives saw the crucial importance of pricing, but few of them said that their companies had figured out how to turn it into a means for consistently winning in the marketplace. Their skills, resources, and tools were falling far short of what they needed to achieve their potential.

The Challenge of Pricing in Retail

Executing a successful pricing strategy in retail requires dexterous management of numerous complex elements.

Targeting Customer Segments. Retailers need to make sure that they are developing relevant promotions based on consumers’ interests, location, gender, life situation, and other factors. After all, a person without children typically isn’t going to be interested in a 50-percent-off sale on kids’ clothing. Retailers also need to be sensitive to the way their consumers are oriented toward price, quality, and experience. A large discount, for example, may not attract a regular shopper who isn’t price sensitive.

Shaping Consumers’ Perceptions of Price. There are prices—and then there are consumers’ perceptions of those prices. Retailers that learn to shape perceptions will gain a particular advantage. For instance, communicating value in addition to price may attract more consumers, but it’s crucial that retailers get the message right. The perception of value for a consumer who buys products offered at “everyday low prices,” for instance, will not be the same as one for a consumer buying identical products that are offered at a relatively high price but then sometimes steeply discounted through promotions, markdowns, or at the register. The value communicated in the latter tactics is just not as easy to discern as the former. Reducing prices on select product categories that more often affect overall price perception, while increasing prices where customers are less price sensitive, will shape customers’ perceptions far more effectively.

Distinguishing Between Short-Term and Long-Term Tactics. Shaping price perception in the short term can be challenging, but trying to influence perception over time can be even more difficult. Companies may make a series of ostensibly correct short-term moves—by boldly and publicly announcing a pricing strategy, for example—but then face increased consumer scrutiny that, over the long term, has a cumulatively negative effect on perceptions.

Building Category Price Ladders. A price ladder clearly articulates to the consumer a company’s map from an opening price point up to a premium price point—from good to better to best. For example, in the men’s shirt department at a mainline department store, an opening-price-point item might be a store-brand shirt that retails for $30. Beyond that price, retailers need to articulate to customers why they should trade up: perhaps a higher quality fabric, better stitching, or a more stylish design.

Yet when we dug deeper into these issues with our respondents, we found that over 60 percent felt as if their companies were average at best in nearly all of these and other critical areas we surveyed. (See Exhibit 1.)

Retailers had the greatest challenges in three areas. (The number in parentheses represents the percentage of retailers rating themselves as below average or average in each area.)

- Taking Advantage of Channel-Specific Opportunities Online (75 percent). A typical apparel retailer, for example, might offer all customers in a given location the same in-store prices. But that retailer could strengthen its pricing strategy by also offering targeted promotions that drive individual customers to buy online—provided, of course, that it has the right online strategy and analytics to support the move.

- Maximizing In-Store Pricing Communications (74 percent). We observed a number of food retailers, for instance, using signs and banners to promote vendor-funded products instead of their own low-priced items in categories such as milk and eggs, where consumers truly compare prices across competitors. Best-in-class store pricing communications can optimize a retailer’s value impression.

- Differentiating Prices by Store Cluster and Zone (70 percent). Retailers can offer different prices based on factors like population density, demographics, and strength of a store’s brand. For example, we find that restaurant chains are able to command higher prices in upper-income and tourist areas, but they are often best served offering lower prices in areas that they are trying to penetrate.

In only one area did more than 40 percent of executives feel that their company was above average or excellent: passing through cost increases in raw materials. In our experience, cost remains the crudest of all inputs to pricing. Simplistic cost-plus pricing that passes through costs in direct proportion to their increase can leave profits on the table.

That’s because the approach fails to take into account consumer preferences overall, let alone at the level of a customer segment. Consumers’ willingness to pay for a product is not typically tied to the cost of that product. Companies with a sophisticated pricing approach will have very different gross margin structures across product categories, depending on the role of any given category in a customer’s decision to visit a store or purchase an item. Successful retailers drive traffic by pricing closer to competition and accepting lower margins on items where consumers compare prices. Retailers have greater pricing flexibility, however, on items that are more specialized or more impulse driven.

Furthermore, cost-plus pricing does not necessarily reflect competitive realities. For example, the cost of a key input, such as wheat, may go up for a particular bakery but not for its competitor, which has a hedging strategy. If the bakery raises its prices to try to offset the increased cost, it’s probably going to lose volume to the competitor that didn’t have to increase prices.

Key Capabilities for Pricing Effectiveness

To better understand how executives believe that key capabilities affect their capacity to meet the challenges they face, we focused on four areas: communications, competitive analysis, organization, and systems and tools.

Effectively communicating pricing strategies to the field is a true capabilities challenge in retail: about half of our respondents believed that they were unable to do so. Companies with decentralized execution in pricing often have great technical people who rigorously take all the right research and analytical steps but lack the ability to simplify and communicate pricing decisions at the local level. At the same time, the people out in the field may not necessarily have the analytical capabilities or context to make fully informed decisions. Those companies just don’t have the right skill sets at either end to get their top-level thinking implemented.

The Internet has turned competitive analysis into a particularly thorny challenge in today’s complex environment. A national big-box retailer with a major online presence, for example, may be forced to match in-store prices with online offers to avoid complaints from consumers who compare the two. Companies must also contend with consumers who use retail locations to “showroom” a product before they buy elsewhere.

Similarly, retailers no longer have the luxury of worrying only about the competitor across the street. Instead, they may have to focus on a small company in another part of the country that’s shipping products through a partnership with a major online retailer. Sometimes a large national retailer might be trying to compete against smaller regional or local businesses with different economic structures or much lower labor costs.

In terms of organization, respondents at retailers with dedicated pricing teams said that the groups tended to be small: more than 70 percent said that their company has fewer than 20 employees dedicated to pricing. They also reported that decision making was often spread across multiple functions—such as marketing, merchandising, and sales—making internal coordination less than ideal. More than a quarter of chief merchants and category managers said that they don’t sufficiently own pricing decisions.

Pricing systems and tools, according to survey respondents, aren’t able to adapt to competitors’ moves and adjust to the increasingly dynamic pricing environment quickly enough. Most pricing technology is still homegrown and ad hoc, built internally using Excel or Access software systems, with third-party software deployed only sparingly. Much of it is also more than five years old and outdated. Satisfaction was lowest in systems and tools for pricing strategy alignment, price optimization, and market share measurement.

The industry standard now involves tracking competitors and changing prices nearly instantaneously. But older tools don’t allow much flexibility in adjusting prices dynamically based on competition. And they also don’t work with the large amounts of real-time, unstructured, so-called “big data” that increasingly influence decision making.

A Better Way to Price

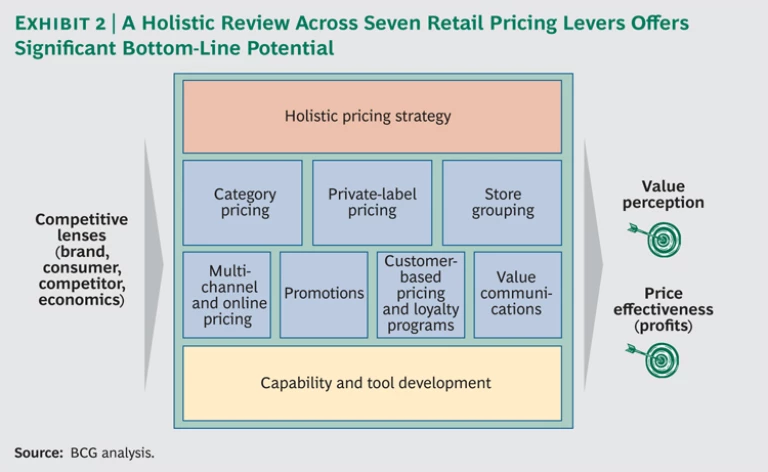

In our experience, retailers that take a series of critical, interconnected steps have the greatest potential for becoming best in class. (See Exhibit 2.)

Build a robust fact base to set the context for a pricing strategy. Effective retailers define their consumer value impression by drawing on multiple inputs: brand strategy, consumer behavior, the competitive space, and category economics.

Develop a holistic pricing strategy. An integrated and coordinated approach cascades through all the major elements of pricing and value, and it crosses all the relevant functions—most commonly including marketing, merchandising, and finance.

Work through the key elements of a pricing model. Effective strategies examine such aspects as base pricing within categories, the impact of loyalty programs, the role of private-label products in communicating value, and the right roles and alignment of promotional, multichannel, and store-specific prices.

Optimize the organization and systems. The highest performers support their pricing strategies with thoughtful organizational design. They establish clear decision rights across functions and provide effective coordination mechanisms, an appropriate level of dedicated pricing resources, and tools to foster decision making. Creating a centralized pricing team has been helpful for many companies as well.

The survey respondents recognized how difficult it can be to turn pricing into a competitive advantage. Our experience, however, suggests that a strategic, coordinated approach can translate into a greatly enhanced customer impression while also driving significantly more dollars to the bottom line.