The oil industry holds relatively few surprises for strategists. Things change, of course, sometimes dramatically, but in relatively predictable ways. Planners know, for instance, that global supply will rise and fall as geopolitical forces play out and new resources are discovered and exploited. They know that demand will rise and fall with incomes, GDPs, weather conditions, and the like. Because these factors are outside companies’ and their competitors’ control and barriers to entry are so high, no one is really in a position to change the game much. A company carefully marshals its unique capabilities and resources to stake out and defend its competitive position in this fairly stable firmament.

The internet software industry would be a nightmare for an oil industry strategist. Innovations and new companies pop up frequently, seemingly out of nowhere, and the pace at which companies can build—or lose—volume and market share is head spinning. A major player like Microsoft or Google or Facebook can, without much warning, introduce some new platform or standard that fundamentally alters the basis of competition. In this environment, competitive advantage comes from reading and responding to signals faster than your rivals do, adapting quickly to change, or capitalizing on technological leadership to influence how demand and competition evolve.

Clearly, the kinds of strategies that would work in the oil industry have practically no hope of working in the far less predictable and far less settled arena of internet software. And the skill sets that oil and software strategists need are worlds apart as well, because they operate on different time scales, use different tools, and have very different relationships with the people on the front lines who implement their plans. Companies operating in such dissimilar competitive environments should be planning, developing, and deploying their strategies in markedly different ways. But all too often, our research shows, they are not.

That is not for want of trying. Responses from a recent BCG survey of 120 companies around the world in 10 major industry sectors show that executives are well aware of the need to match their strategy-making processes to the specific demands of their competitive environments. Still, the survey found, in practice many rely instead on approaches that are better suited to predictable, stable environments, even when their own environments are known to be highly volatile or mutable.

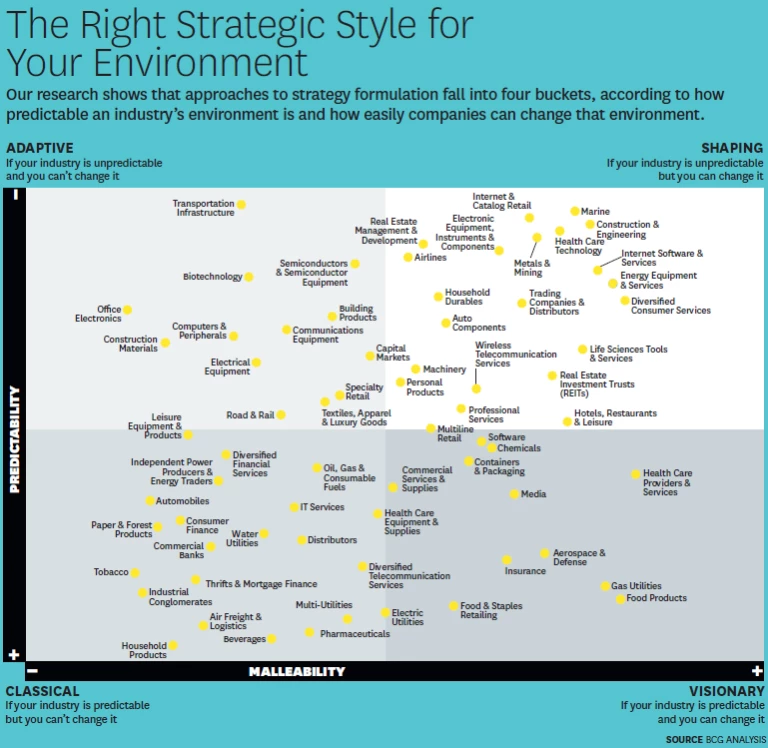

What’s stopping these executives from making strategy in a way that fits their situation? We believe they lack a systematic way to go about it—a strategy for making strategy. Here we present a simple framework that divides strategy planning into four styles according to how predictable your environment is and how much power you have to change it. Using this framework, corporate leaders can match their strategic style to the particular conditions of their industry, business function, or geographic market.

How you set your strategy constrains the kind of strategy you develop. With a clear understanding of the strategic styles available and the conditions under which each is appropriate, more companies can do what we have found that the most successful are already doing—deploying their unique capabilities and resources to better capture the opportunities available to them.

When the Cold Winds Blow

There are circumstances in which none of our strategic styles will work well: when access to capital or other critical resources is severely restricted, by either a sharp economic downturn or some other cataclysmic event. Such a harsh environment threatens the very viability of a company and demands a fifth strategic style—survival.

As its name implies, a survival strategy requires a company to focus defensively—reducing costs, preserving capital, trimming business portfolios. It is a short-term strategy, intended to clear the way for the company to live another day. But it does not lead to any long-term growth strategy. Companies in survival mode should therefore look ahead, readying themselves to assess the conditions of the new environment and to adopt an appropriate growth strategy once the crisis ends.

Finding the Right Strategic Style

Strategy usually begins with an assessment of your industry. Your choice of strategic style should begin there as well. Although many industry factors will play into the strategy you actually formulate, you can narrow down your options by considering just two critical factors: predictability (How far into the future and how accurately can you confidently forecast demand, corporate performance, competitive dynamics, and market expectations?) and malleability (To what extent can you or your competitors influence those factors?).

Put these two variables into a matrix, and four broad strategic styles—which we label classical, adaptive, shaping, and visionary—emerge. (See the exhibit “The Right Strategic Style for Your Environment.”) Each style is associated with distinct planning practices and is best suited to one environment. Too often strategists conflate predictability and malleability—thinking that any environment that can be shaped is unpredictable—and thus divide the world of strategic possibilities into only two parts (predictable and immutable or unpredictable and mutable), whereas they ought to consider all four. So it did not surprise us to find that companies that match their strategic style to their environment perform significantly better than those that don’t. In our analysis, the three-year total shareholder returns of companies in our survey that use the right style were 4% to 8% higher, on average, than the returns of those that do not.

Let’s look at each style in turn.

Classical. When you operate in an industry whose environment is predictable but hard for your company to change, a classical strategic style has the best chance of success. This is the style familiar to most managers and business school graduates—five forces, blue ocean, and growth-share matrix analyses are all manifestations of it. A company sets a goal, targeting the most favorable market position it can attain by capitalizing on its particular capabilities and resources, and then tries to build and fortify that position through orderly, successive rounds of planning, using quantitative predictive methods that allow it to project well into the future. Once such plans are set, they tend to stay in place for several years. Classical strategic planning can work well as a stand-alone function because it requires special analytic and quantitative skills, and things move slowly enough to allow for information to pass between departments.

Oil company strategists, like those in many other mature industries, effectively employ the classical style. At a major oil company such as ExxonMobil or Shell, for instance, highly trained analysts in the corporate strategic-planning office spend their days developing detailed perspectives on the long-term economic factors relating to demand and the technological factors relating to supply. These analyses allow them to devise upstream oil-extraction plans that may stretch 10 years into the future and downstream production-capacity plans up to five years out. It could hardly be otherwise, given the time needed to find and exploit new sources of oil, to build production facilities, and to keep them running at optimum capacity. These plans, in turn, inform multiyear financial forecasts, which determine annual targets that are focused on honing the efficiencies required to maintain and bolster the company’s market position and performance. Only in the face of something extraordinary—an extended Gulf war; a series of major oil refinery shutdowns—would plans be seriously revisited more frequently than once a year.

Adaptive. The classical approach works for oil companies because their strategists operate in an environment in which the most attractive positions and the most rewarded capabilities today will, in all likelihood, remain the same tomorrow. But that has never been true for some industries, and, as has been noted before in these pages (“ Adaptability: The New Competitive Advantage ,” by Martin Reeves and Mike Deimler, HBR July–August 2011), it’s becoming less and less true where global competition, technological innovation, social feedback loops, and economic uncertainty combine to make the environment radically and persistently unpredictable. In such an environment, a carefully crafted classical strategy may become obsolete within months or even weeks.

Companies in this situation need a more adaptive approach, whereby they can constantly refine goals and tactics and shift, acquire, or divest resources smoothly and promptly. In such a fast-moving, reactive environment, when predictions are likely to be wrong and long-term plans are essentially useless, the goal cannot be to optimize efficiency; rather, it must be to engineer flexibility. Accordingly, planning cycles may shrink to less than a year or even become continual. Plans take the form not of carefully specified blueprints but of rough hypotheses based on the best available data. In testing them out, strategy must be tightly linked with or embedded in operations, to best capture change signals and minimize information loss and time lags.

Specialty fashion retailing is a good example of this. Tastes change quickly. Brands become hot (or not) overnight. No amount of data or planning will grant fashion executives the luxury of knowing far in advance what to make. So their best bet is to set up their organizations to continually produce, roll out, and test a variety of products as quickly as they can, constantly adapting production in the light of new learning.

The Spanish retailer Zara uses the adaptive approach. Zara does not rely heavily on a formal planning process; rather, its strategic style is baked into its flexible supply chain. It maintains strong ties with its 1,400 external suppliers, which work closely with its designers and marketers. As a result, Zara can design, manufacture, and ship a garment to its stores in as little as two to three weeks, rather than the industry average of four to six months. This allows the company to experiment with a wide variety of looks and make small bets with small batches of potentially popular styles. If they prove a hit, Zara can ramp up production quickly. If they don’t, not much is lost in markdowns. (On average, Zara marks down only 15% of its inventory, whereas the figure for competitors can be as high as 50%.) So it need not predict or make bets on which fashions will capture its customers’ imaginations and wallets from month to month. Instead it can respond quickly to information from its retail stores, constantly experiment with various off erings, and smoothly adjust to events as they play out.

Zara’s strategic style requires relationships among its planners, designers, manufacturers, and distributors that are entirely different from what a company like ExxonMobil needs. Nevertheless, Exxon’s strategists and Zara’s designers have one critical thing in common: They take their competitive environment as a given and aim to carve out the best place they can within it.

Shaping. Some environments, as internet software vendors well know, can’t be taken as given. For instance, in new or young high-growth industries where barriers to entry are low, innovation rates are high, demand is very hard to predict, and the relative positions of competitors are in flux, a company can often radically shift the course of industry development through some innovative move. A mature industry that’s similarly fragmented and not dominated by a few powerful incumbents, or is stagnant and ripe for disruption, is also likely to be similarly malleable.

In such an environment, a company employing a classical or even an adaptive strategy to find the best possible market position runs the risk of selling itself short, being overrun by events, and missing opportunities to control its own fate. It would do better to employ a strategy in which the goal is to shape the unpredictable environment to its own advantage before someone else does—so that it benefits no matter how things play out.

Like an adaptive strategy, a shaping strategy embraces short or continual planning cycles. Flexibility is paramount, little reliance is placed on elaborate prediction mechanisms, and the strategy is most commonly implemented as a portfolio of experiments. But unlike adapters, shapers focus beyond the boundaries of their own company, often by rallying a formidable ecosystem of customers, suppliers, and/or complementors to their cause by defining attractive new markets, standards, technology platforms, and business practices. They propagate these through marketing, lobbying, and savvy partnerships. In the early stages of the digital revolution, internet software companies frequently used shaping strategies to create new communities, standards, and platforms that became the foundations for new markets and businesses.

That’s essentially how Facebook overtook the incumbent MySpace in just a few years. One of Facebook’s savviest strategic moves was to open its social-networking platform to outside developers in 2007, thus attracting all manner of applications to its site. Facebook couldn’t hope to predict how big or successful any one of them would become. But it didn’t need to. By 2008 it had attracted 33,000 applications; by 2010 that number had risen to more than 550,000. So as the industry developed and more than two-thirds of the successful social-networking apps turned out to be games, it was not surprising that the most popular ones—created by Zynga, Playdom, and Playfish—were operating from, and enriching, Facebook’s site. What’s more, even if the social-networking landscape shifts dramatically as time goes on, chances are the most popular applications will still be on Facebook. That’s because by creating a flexible and popular platform, the company actively shaped the business environment to its own advantage rather than merely staking out a position in an existing market or reacting to changes, however quickly, after they’d occurred.

Visionary. Sometimes, not only does a company have the power to shape the future, but it’s possible to know that future and to predict the path to realizing it. Those times call for bold strategies—the kind entrepreneurs use to create entirely new markets (as Edison did for electricity and Martine Rothblatt did for XM satellite radio), or corporate leaders use to revitalize a company with a wholly new vision—as Ratan Tata is trying to do with the ultra-affordable Nano automobile. These are the big bets, the build-it-and- they-will-come strategies.

Like a shaping strategist, the visionary considers the environment not as a given but as something that can be molded to advantage. Even so, the visionary style has more in common with a classical than with an adaptive approach. Because the goal is clear, strategists can take deliberate steps to reach it without having to keep many options open. It’s more important for them to take the time and care they need to marshal resources, plan thoroughly, and implement correctly so that the vision doesn’t fall victim to poor execution. Visionary strategists must have the courage to stay the course and the will to commit the necessary resources.

Back in 1994, for example, it became clear to UPS that the rise of internet commerce was going to be a bonanza for delivery companies, because the one thing online retailers would always need was a way to get their offerings out of cyberspace and onto their customers’ doorsteps. This future may have been just as clear to the much younger and smaller FedEx, but UPS had the means—and the will—to make the necessary investments. That year it set up a cross-functional committee drawn from IT, sales, marketing, and finance to map out its path to becoming what the company later called “the enablers of global e-commerce.” The committee identified the ambitious initiatives that UPS would need to realize this vision, which involved investing some $1 billion a year to integrate its core package-tracking operations with those of web providers and make acquisitions to expand its global delivery capacity. By 2000 UPS’s multibillion-dollar bet had paid off: The company had snapped up a whopping 60% of the e-commerce delivery market.

Avoiding the Traps

In our survey, fully three out of four executives understood that they needed to employ different strategic styles in different circumstances. Yet judging by the practices they actually adopted, we estimate that the same percentage were using only the two strategic styles—classic and visionary—suited to predictable environments. (See “Which Strategic Style Is Used the Most?”) That means only one in four was prepared in practice to adapt to unforeseeable events or to seize an opportunity to shape an industry to his or her company’s advantage. Given our analysis of how unpredictable their business environments actually are, this number is far too low. Understanding how different the various approaches are and in which environment each best applies can go a long way toward correcting mismatches between strategic style and business environment. But as strategists think through the implications of the framework, they need to avoid three traps we have frequently observed.

Which Strategic Style Is Used the Most?

Our survey found that companies were most often using the two styles best suited to predictable environments—classical and visionary—even when their environments were clearly unpredictable.

- 9% Shaping

- 16% Adaptive

- 35% Classical

- 40% Visionary

Are you clinging to the wrong strategy style?

A clear estimation of your industry’s predictability and malleability is key to picking the right strategy style. But our survey of more than 120 companies in 10 industries showed that companies don’t do this well: Their estimates rarely matched our objective measures. They consistently overestimated both predictability and malleability.

Misplaced confidence. You can’t choose the right strategic style unless you accurately judge how predictable and malleable your environment is. But when we compared executives’ perceptions with objective measures of their actual environments, we saw a strong tendency to overestimate both factors. Nearly half the executives believed they could control uncertainty in the business environment through their own actions. More than 80% said that achieving goals depended on their own actions more than on things they could not control.

Unexamined habits. Many executives recognized the importance of building the adaptive capabilities required to address unpredictable environments, but fewer than one in five felt sufficiently competent in them. In part that’s because many executives learned only the classical style, through experience or at business school. Accordingly, we weren’t surprised to find that nearly 80% said that in practice they begin their strategic planning by articulating a goal and then analyzing how best to get there. What’s more, some 70% said that in practice they value accuracy over speed of decisions, even when they are well aware that their environment is fast-moving and unpredictable. As a result, a lot of time is being wasted making untenable predictions when a faster, more iterative, and more experimental approach would be more effective. Executives are also closely attuned to quarterly and annual financial reporting, which heavily influences their strategic-planning cycles. Nearly 90% said they develop strategic plans on an annual basis, regardless of the actual pace of change in their business environments—or even what they perceive it to be.

Culture mismatches. Although many executives recognize the importance of adaptive capabilities, it can be highly countercultural to implement them. Classical strategies aimed at achieving economies of scale and scope often create company cultures that prize efficiency and the elimination of variation. These can of course undermine the opportunity to experiment and learn, which is essential for an adaptive strategy. And failure is a natural outcome of experimentation, so adaptive and shaping strategies fare poorly in cultures that punish it.

Avoiding some of these traps can be straightforward once the differing requirements of the four strategic styles are understood. Simply being aware that adaptive planning horizons don’t necessarily correlate well with the rhythms of financial markets, for instance, might go a long way toward eliminating ingrained planning habits. Similarly, understanding that the point of shaping and visionary strategies is to change the game rather than to optimize your position in the market may be all that’s needed to avoid starting with the wrong approach.

Being more thoughtful about metrics is also helpful. Although companies put a great deal of energy into making predictions year after year, it’s surprising how rarely they check to see if the predictions they made in the prior year actually panned out. We suggest regularly reviewing the accuracy of your forecasts and also objectively gauging predictability by tracking how often and to what extent companies in your industry change relative position in terms of revenue, profitability, and other performance measures. To get a better sense of the extent to which industry players can change their environment, we recommend measuring industry youthfulness, concentration, growth rate, innovation rate, and rate of technology change—all of which increase malleability.

Operating in Many Modes

Matching your company’s strategic style to the predictability and malleability of your industry will align overall strategy with the broad economic conditions in which the company operates. But various company units may well operate in differing subsidiary or geographic markets that are more or less predictable and malleable than the industry at large. Strategists in these units and markets can use the same process to select the most effective style for their particular circumstances, asking themselves the same initial questions: How predictable is the environment in which our unit operates? How much power do we have to change that environment? The answers may vary widely. We estimate, for example, that the Chinese business environment overall has been almost twice as malleable and unpredictable as that in the United States, making shaping strategies often more appropriate in China.

Similarly, the functions within your company are likely to operate in environments that call for differing approaches to departmental planning. It’s easy to imagine, for instance, that within the auto industry a classical style would work well for optimizing production but would be inappropriate for the digital marketing department, which probably has a far greater power to shape its environment (after all, that’s what advertising aims to do) and would hardly benefit from mapping out its campaigns years in advance.

If units or functions within your company would benefit from operating in a strategic style other than the one best suited to your industry as a whole, it follows that you will very likely need to manage more than one strategic style at a time. Executives in our survey are well aware of this: In fact, fully 90% aspired to improve their ability to manage multiple styles simultaneously. The simplest but also the least flexible way to do this is to structure and run funcfunctions, regions, or business units that require differing strategic styles separately. Allowing teams within units to select their own styles gives you more flexibility in diverse or fast-changing environments but is generally more challenging to realize. (For an example of a company that has found a systematic way to do it, see “The Ultimate in Strategic Flexibility,” below.)

The Ultimate in Strategic Flexibility

Haier, a Chinese home-appliance manufacturer, may have taken strategic flexibility just about as far as it can go. The company has devised a system in which units as small as an individual can effectively use differing styles.

How does it manage this? Haier’s organization comprises thousands of minicompanies, each accountable for its own P&L. Any employee can start one of them. But there are no cost centers in the company—only profit centers. Each minicompany bears the fully loaded costs of its operations, and each party negotiates with the others for services; even the finance department sells its services to the others. Every employee is held accountable for achieving profits. An employee’s salary is based on a simple formula: base salary × % of monthly target achieved + bonus (or deduction) based on individual P&L. In other words, if a minicompany achieves none of its monthly target (0%), the employees in it receive no salary that month.

Operating at this level of flexibility can be as rewarding as it is daunting. Near bankruptcy in 1985, Haier has since become the world’s largest home-appliance company—ahead of LG, Samsung, GE, and Whirlpool.

Finally, a company moving into a different stage of its life cycle may well require a shift in strategic style. Environments for start-ups tend to be malleable, calling for visionary or shaping strategies. In a company’s growth and maturity phases, when the environment is less malleable, adaptive or classical styles are often best. For companies in a declining phase, the environment becomes more malleable again, generating opportunities for disruption and rejuvenation through either a shaping or a visionary strategy.

Once you have correctly analyzed your environment, not only for the business as a whole but for each of your functions, divisions, and geographic markets, and you have identified which strategic styles should be used, corrected for your own biases, and taken steps to prime your company’s culture so that the appropriate styles can successfully be applied, you will need to monitor your environment and be prepared to adjust as conditions change over time. Clearly that’s no easy task. But we believe that companies that continually match their strategic styles to their situation will enjoy a tremendous advantage over those that don’t.

This article originally appeared in the

Harvard Business Review

and is republished here with permission.