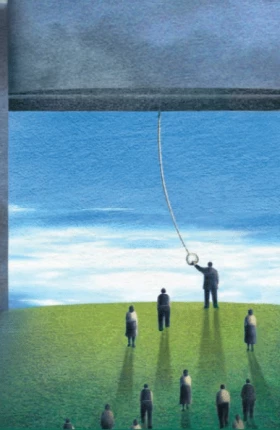

With the financial crisis behind us, companies in the financial services industry are now dealing with an environment of slow growth, lower returns, and tarnished reputations. To succeed in this context—which we at BCG call the “new new normal”—and return to historical earnings growth rates, industry players must shed long-held assumptions and rethink every aspect of their operations.

Martha Craumer, senior writer at The Boston Consulting Group, spoke with Michael Shanahan , senior partner and managing director in the firm's Boston office, about the challenges facing the financial services industry today and how companies can manage these changes more effectively.

What trends are you seeing in the financial services industry?

The industry has entered into a period of low to medium growth, lower returns, and regulatory uncertainty. Most players have now accepted that what they had originally hoped would be a two- or three-year challenge before a return to historical trajectories of growth is now not going to happen—or certainly not in Europe and North America. Most have already downsized their headcounts, reduced costs, are transforming their global operating models, and are learning to live with a less profitable revenue mix than they were used to.

This is a huge challenge for most players. Few of today's financial executives have experienced such a prolonged depression of growth and profitability. Fewer still have led in times of such acute uncertainty, not just with regard to regulatory reforms and future capital requirements, but also to how financial markets will develop going forward. And none have had the experience of being in the bull's-eye of government, regulatory, and general public scrutiny as they are today. And don't forget, for the consumer end of financial services, such as retail banking and brokerage, customer trust has diminished—and with it, customer loyalty as well. Taken together, these factors mark a true crisis that will demand a pretty fundamental rethinking of strategy.

How should management teams deal with these challenges and changes?

They need to take action on three fronts. First, given that most of the low-hanging fruit is already gone, they should cut costs strategically and sustainably, in ways that allow them to do more with less over the long term. At the same time, productivity must be increased. Global operating models cannot only be about shifting higher-wage jobs to lower-wage environments. To succeed over the long term, global operations must deliver more efficient and effective services back to the company and embrace a culture of customer service and continuous improvement. Making progress in these areas also demands that the corporate center and the business units collaborate more closely.

Second, management teams must refocus on the revenue line. At the core of much of the current challenge is the reduced quality of assets: less revenue per asset, less profitability per revenue unit. Managers must do a better job of developing deeper relationships with customers, learning more about their needs and building a bigger share of wallet by better meeting those needs. This means mobilizing frontline sales, product specialists, and relationship managers differently than in the past, measuring them not only on net sales but on customer share of wallet. It also means getting intimate enough with the customer that you can rethink pricing.

And finally, companies need to invest in innovation. Now more than ever is the time to develop a culture of "shots on goal" versus safe bets, fully exploiting what technology can bring in such areas as big data, digitization, "peopleless" automation, and mobile settlements and banking.

According to a number of recent surveys, employees in the financial services sector have never been so disengaged and demoralized. How can banks make these ambitious changes when so many employees are checked out?

That's a really good question. It is well known that 50 to 70 percent of change efforts fail, so the odds are already stacked against them. Add to that a situation where employees lack confidence that their companies have a winning strategy for the future and an all too common belief that senior management is not committed to change. Without addressing these issues, companies will fail to recover their performance. That means leaders must get deeply aligned and committed to a pathway that they can confidently and authentically articulate to their people.

This alignment on key messages and the path forward must cascade down to middle managers—those at levels two and three—all of whom must be able to explain to their people what changes must be made and why, and what the impact will be on employees. People for the most part behave rationally, so when they stand back and resist, they do so invariably because what they hear and what they see are two different things. They need to believe that their boss gets it and that, if they make the effort to change behavior and try something new, they will not be left hanging out to dry.

People need their leaders to be visible, especially during difficult times. The most effective leaders walk around, are accessible, and answer questions openly—even if they don't have all the answers. At one financial services company, the CEO and his entire management team went around to every office, sat on stools in a town hall format, listened to employees' concerns, and answered questions openly and honestly. The fact that the whole team was there, clearly aligned and working together, boosted employee confidence.

Culture is formed more during the worst of times than the best of times. If layoffs were part of the equation, the employees who remain are likely to feel survivor's guilt, and their morale and performance may suffer—especially if they think that the layoffs were only to reduce costs. But if they believe the changes were made to fundamentally reshape the company for future stability and success, and that people were treated with respect, then they are more likely reward the organization with their best efforts.

What else gets in the way of effective change ?

Change programs often move too slowly—or stall entirely. It's better to have fewer programs that are 100 percent completed than a large, ambitious group of initiatives that lose momentum and never deliver results, a trap many companies fall into. The cost to a company's health and morale is huge if a change program doesn't deliver impact.

Many leaders think that once a program is in place, the job is done. But that's really just the beginning. You need rigor-tested plans and strong program management that tracks progress, removes obstacles, course corrects, and sees a program through to the last mile. This point is strongly made by the Economist Intelligence Unit in its change-management surveys, which consistently highlight two key success factors: the commitment of senior leadership and clearly defined objectives.

Finally, how can financial services companies regain the trust of their customers?

This is a huge challenge, for retail and institutional banks alike. When trust of intention, product, and mission are lost, getting it back is difficult. And retention is also a major issue. Banks must find ways to lock in business by cross-selling, creating a more memorable customer experience, using technology in new ways, providing value-adding services, and developing new products that are truly differentiating. But improving product design and the customer experience is difficult with front-office employees who are unhappy and don't feel valued. So banks have a rocky road ahead. That's why re-engaging the frontline employees is crucial.