Not so long ago, Nokia was a powerhouse in the mobile-phone business—arguably the industry’s dominant brand worldwide, with a market capitalization that had made the company one of the largest blue chips in Europe.

Then along came Apple.

The iPhone shattered the prevailing ideas of value creation in personal mobile communications. Apple was not just making and selling a product, it was bringing together a range of attractive offerings from a whole universe of partners, large and small. Yet despite the size and diversity of this universe, the offerings were tightly integrated: Apple was guaranteeing a homogenous and pleasing experience for the customer—a crucial factor in its success.

For Nokia, there was worse to come. The company began losing ground to manufacturers of phones using the Android operating system—in particular, the attractive, feature-rich handsets from Samsung. When Nokia’s new chief executive sent out an internal wake-up memo, he described the company’s challenges this way: “Our competitors are not taking our market share with devices; they are taking our market share with an entire ecosystem.”

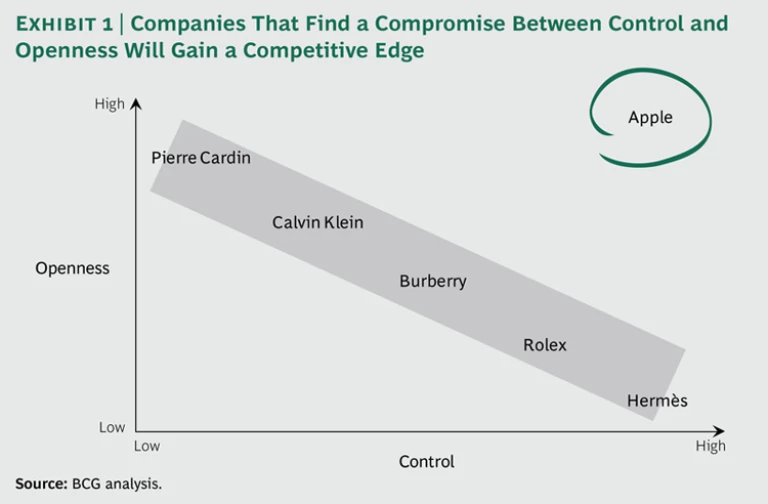

There is a powerful message here for CEOs in the luxury goods and services sector. By assembling such a powerful coalition, Apple did a very unusual thing: it established a balance between control and openness—two historically incompatible ways of managing a brand. (See Exhibit 1.) Apple had long been famous for its tightly controlled, or closed, business model. Yet the company had opened itself up to a host of partners, from giant telecom companies to independent contractors.

More and more luxury houses will have to master that balancing act. Because most luxury companies feel strongly about maintaining control of their brands, they have been reluctant to work with partners on strategic projects and have retained most aspects of their value chains in-house. But that approach is rapidly being challenged by market circumstances. In today’s “wiki world” of increasing openness—between customers and suppliers and between shoppers and brands, and where the lines between competition and cooperation have begun to blur—companies increasingly benefit by bringing in ideas and expertise from the outside. That is especially so in the luxury world, where future growth for many companies will depend on success in new market categories, locations, and channels—and where partnerships, when thoughtfully and carefully orchestrated, can make the difference between success and failure.