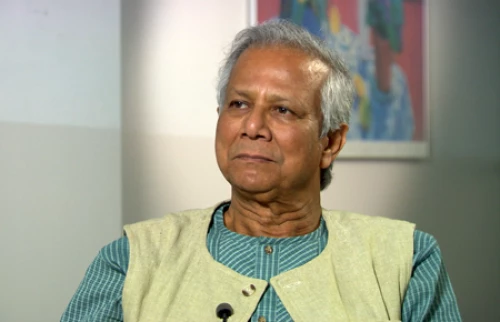

The concept of “social businesses”—companies that try to solve a social problem by applying business principles—has attracted significant attention in recent years. Professor Muhammad Yunus, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, and founder of the Grameen Bank, is commonly considered the thought father and early implementer of the social business concept. He initiated and developed more than 20 social businesses in Bangladesh, many of them in cooperation with multinational corporate partners.

Ulrich Villis, an associate director in the Munich office of The Boston Consulting Group and leader of the firm’s social impact practice in Europe, recently spoke with Professor Yunus about how social business can provide benefits to society as well as to the corporate sector, and his vision for the future. Edited excerpts from their conversation follow.

About Muhammad Yunus

At a Glance

Born: June 28, 1940

Chittagong, Bangladesh

Education

Doctorate degree in economics, Vanderbilt University, 1969

Master’s of arts degree in economics, Dhaka University, 1961

Bachelor’s of arts degree in economics, Dhaka University, 1960

Career Highlights

2011–present, chairman, Yunus Social Business

2011–present, chairman, Yunus Centre

1983–2011, founder and managing director, Grameen Bank

1975–1989, director, Rural Economics Programme, Chittagong, Bangladesh

1972–1975, head of economics department, Chittagong University

1970–1972, assistant professor of economics, Middle Tennessee State University

Outside Activities

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, 2006

Recipient, U.S. Congressional Gold Medal

Named one of Foreign Policy magazine's “Top 100 Global Thinkers” in 2008

Chancellor of Glasgow Caledonian University in Scotland

Member, Board of Directors, United Nations Foundation

Founding Member, Global Elders

Author, Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism (2008)

Author, Banker to the Poor (1997)

What, in your words, is a social business?

The quickest way that I can describe it is a nondividend company that solves human problems. The investor can take back the investment money out of the business over time, but he or she is not interested in making any additional money or dividend out of it for himself or herself. So that becomes a social business. It is focused on solving a human problem, unlike conventional businesses, which want to make money as their prime objective, and everything else fits into that. Here, the prime objective of the company is to solve human problems in a sustainable way.

What you target is mostly the very poor, particularly if you look at the developing world. And the concept implies that they pay a price for the products or services. Now, how do you reconcile the two?

We charge a fee or price for providing a service because then it becomes sustainable. We created an eye-care hospital at which we provide cataract operations, and we charge the market price, which is $30 per cataract operation. We make money and we cross-subsidize the cost for people who cannot pay. That way, the whole eye-care hospital covers all its costs and sustains itself. We don’t have to go around raising money to keep it running.

To make an institution self-sustaining is a tremendous power, and if you can bring it to the area of solving social problems, I think it will be a big addition. Along with that, you bring your creative power, you bring your technology—and all of this combined makes it a very powerful idea.

Why should corporations want to engage in building a social business?

Companies find it very useful to bring the creative side of their business and apply it to solving human problems. This will change the nature of the human problems tremendously because suddenly the outburst of the creative power of business directed toward solving problems brings lots of strength that never existed before.

I often hear that there are business benefits as well, because social businesses offer a place for innovation and learning in a different setting. Is that something you see?

We see that a lot. There might be something that you couldn’t do within your company, because your eyes didn’t look in that direction. But once you are here [with the social business], you are creating a new business process, and you learn something that is applicable to the broader company. For example, in Danone’s case, we were insisting that the cup in which the yogurt is delivered [to the poor] shouldn’t be a plastic cup. They said, “We always use a plastic cup.” And I said, “You have always been a money-making company. This is a social business. We should not accept plastic here.” Then what should we use? I said, “You should use biodegradable cups.” So they went around to find material they could use for biodegradable cups. Finally they found it, and it was cornstarch. And they are really excited about it. We started using these biodegradable cups. Today, Danone tells me that they have replaced all of the plastic cups in their parent business.

It’s mutually beneficial: what you do in the profit-making world benefits the social business. And what you do in the social business benefits the profit-making world. There is no conflict between the two. There is a lot of overlap, a lot of synergy. They help each other.

The businesses you created with corporate partners—are they successful now?

Some are, some are still going through the teething process. Any business has a teething process, particularly if it is entering the completely new territory called social business. It is one thing to think aloud, “What should this be?” It is another to put together a business on the ground.

Danone went through lots of problems in the beginning, to make sure that the yogurt tasted right and to make sure it was affordable—because if it’s too expensive, the whole purpose is defeated. If the price of the ingredients goes up, how do you make sure that you can retain the price point you need to continue? So these are the issues: how to reach out to the poorest rather than have a Danone yogurt for rich people. They don’t need it, poor people need it. So how do you do it, how do you ensure that you reach out to the poor families? How do you do the marketing?

But once you have done the prototype, you have contributed an enormous gift to the world. All you have to do now is repeat this, every place. And the problem will be solved in a very sustainable way. All you do is invest the money, and the money comes back. The social business continues to run.

It’s like seed development. Seed development is a very long, drawn-out process, but once you develop that seed, it becomes a miracle seed. All you have to do is have a big seed bag, and you can make plantations and make big fields filled with your crops.

When I visited you in Bangladesh I was impressed by the size and scale that Grameen Shakti has reached. Where does it stand now?

Now we have more than 1 million households with solar home systems. It took us 16 years to reach that point. But it will take only three years to reach the next million because the spirit is so high now. Probably the third million, when we get there, will take less than two years. That’s the kind of thing it is: you build up the steam, build up the speed, and it goes.

Where will the social business movement go?

I am posing a challenge: Let’s have 1 percent of the economy be social businesses in the next five years. That 1 percent will lay the foundation. Once the ground is prepared, moving from 1 percent to 5 percent of the economy will not be difficult, because now the ground will be prepared in every country. Once every country has 1 percent and every city has 1 percent then everybody will know what a social business is. My expectation is that once it is done, everyone will love it.