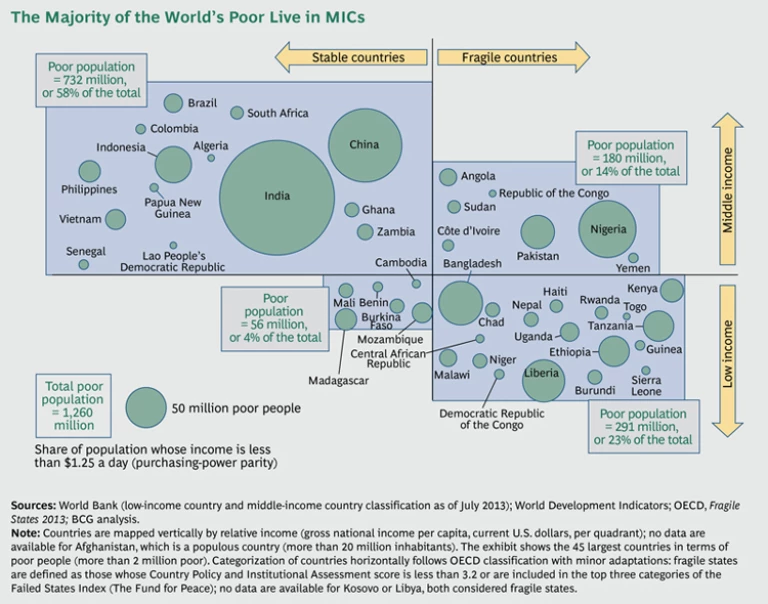

Rapid economic growth in the developing world has turned many once-poor nations such as China, India, Brazil, and Indonesia into middle-income countries (MICs), defined by the World Bank as countries whose annual per capita gross national income ranges from $1,026 to $12,475. With relatively stable governments and growing financial resources, these countries receive less international aid now that they’ve ascended the economic ladder. That is not to say that their social problems have disappeared. Far from it. In fact, despite their relative economic progress, MICs are now home to 72 percent of the world’s poorest people. (See the exhibit below.) Income inequality and growing urban poverty are enormous challenges.

Having largely outgrown the need for traditional aid, however, governments in these countries are striving to reposition themselves as global players in development rather than as aid recipients. To this end, many are investing in innovative programs for fighting poverty, hunger, and disease. For instance, Brazil’s cash-transfer program has greatly improved nutrition among the country’s poorest populations and increased their incomes by about 25 percent since 2000. Mexico’s Oportunidades social-safety-net program has improved the health of low-income people and helps keep students in school longer. The system serves as a model for New York City and Nicaragua.

In this evolving landscape, the balance of power has shifted. Rather than being passive recipients of international aid, governments are now starting to actively choose the services they want from aid agencies, and they are ready to pay for those that support their development agendas.

How can international aid agencies address the most pressing social issues when the governments of MICs are investing in their own programs and no longer need direct delivery of services and commodities such as food, cash, and health care? And how can agencies complement the changing role of national governments that are now taking full ownership of implementing their national development agendas?

What MICs Need and How Agencies Should Respond

To find out the answers to these questions, BCG conducted 115 interviews with aid agencies and governments and made field visits to five MICs. We asked the governments where they see the greatest need for agency support and conducted interviews with aid agencies, exploring their strategies for successfully delivering impact to MICs, as well as their priorities, activities, and needed organizational changes.

Our findings revealed that MIC governments want to work with agencies that can add value in “upstream” activities related to capacity development, advisory services, and advocacy. These activities might include helping MICs develop social programs, providing advice and guidance related to key areas of expertise, and actively lobbying for specific social policies.

Aid agencies are responding to changes in the landscape by moving away from traditional aid delivery toward building partnerships with national governments. They’re becoming topic experts, enriching their service offerings by developing specific expertise, providing more customized products and services, and focusing on capacity development. For instance, the World Bank is emphasizing knowledge products, which it can provide to countries whether or not they use the bank’s grants or loans. In many countries, Unicef is explicitly shifting its focus from implementation to capacity development, advocacy, extended partnerships, and knowledge creation. And the International Fund for Agricultural Development is moving toward knowledge products and innovation. Although the agencies we interviewed all agreed on the need to change how they operate—and are beginning to make those changes—only one had explicitly formulated an MIC strategy.

Five Best Practices

Drawing on our interview findings, we identified five best practices for international aid agencies that want to reposition themselves strategically in MICs:

- Identify key capabilities and develop a clear value proposition. Aid organizations must analyze their skills and areas of expertise, looking for strengths that match national governments’ goals, priorities, issues, and capability gaps. Key strengths might include a strong brand associated with neutrality and competence; expertise in program design or management; global experience on specific topics; technical expertise in areas such as the supply chain, distribution, or child protection; access to global stakeholders; and proven planning and implementation skills. Governments view codified best practices and many years of experience as very valuable assets. For inspiration, look back on the programs your agency has worked on and the knowledge you’ve built through the years. Experience in niche areas may be especially valuable.

- Position your agency as a valuable partner. No longer in need of traditional aid, MIC governments want value-adding services in areas in which they lack adequate expertise or experience. To succeed in this new arena, agencies must be able to add value by playing one or more key roles: advisor, enabler, coordinator, or advocate. Those agencies that can provide advice on how to design an effective social program, for instance, or that have the skills to enable national authorities to implement effective programs will be well positioned to succeed. Similarly, the ability to coordinate a wide range of organizations, NGOs, researchers, universities, and other partners is highly valued, as is the ability to advocate for new social policies through effective lobbying or to provide high-quality analysis as a basis for key policy decisions.

- Strengthen your internal skill set. New activities and roles require new skills. In the past, agencies needed large numbers of staff with experience in operations and implementation. Today, however, agencies may need fewer people with different skills who can act as advisors and enablers. Long-term recruitment strategies must anticipate future demand and start matching existing skills to evolving needs. Experience working with national governments, for instance, might be highly valued. Similarly, there may be a greater need for leadership at the more senior levels to credibly engage with government authorities, build relationships, gain access to key stakeholders, lay the groundwork for effective social development, and develop the capacities of staff members. Because job profiles in the staffing system may capture only traditional roles, descriptions of roles and responsibilities may need updating. Moreover, as some of the needed skills and expertise may not be available in the traditional talent pool, agencies may need to recruit from the private sector, which will require rethinking compensation and recruiting processes.

- Rethink the funding model. No longer dependent on external grants, MIC governments are now largely self-funding and purchase the agency services that they perceive a need for. For agencies, changes in the funding model may make it hard to build up new skills and activities while ensuring the continuity of current programs. To have a sustainable impact, agencies must develop new funding strategies, shifting away from traditional donors to new sources, such as host governments, foundations, the private sector, and impact investment players. The new funding model will require new internal systems for administration, reporting, monitoring, and account management.

- Improve knowledge management. With their local presence, national governments and national NGOs are in the best positions to implement social programs cost-effectively. They look to aid agencies for expertise and experience—and knowledge is the biggest source of competitive advantage for agencies today. Consider systematically documenting your agency’s global experience in the field and developing a platform to organize, capture, share, and apply key lessons within and across countries. Establish a repository with key contacts from past and current projects to preserve institutional memory. Personal connections and access to experts create tremendous value that can set your agency apart. Encourage staff to use organizational knowledge by providing access to experts, materials, and communities of practice. At the same time, create a culture that values knowledge sharing as much as project work and service delivery. Better knowledge systems can help staff reapply the lessons learned by others and minimize waste of critical resources.

Taken together, these best practices can help agencies plan for the changing MIC landscape and position themselves for success.

New Strategies in Action: World Food Programme in India

The focus of the World Food Programme (WFP) has been the quick and efficient delivery of food in emergency situations. But an MIC such as India no longer needs this type of direct donation. The country’s government runs one of the world’s largest food-distribution programs, which provides monthly rations of subsidized food commodities to 400 million people at a cost of some $12 billion per year. Unfortunately, the program has been plagued by leakage and corruption. According to a 2005 study by the Planning Commission of the Government of India, only about half the food reaches the intended beneficiaries.

Recognizing India’s changing needs, WFP completely overhauled its traditional approach. Instead of donating food, the agency has been working closely with the government to outline plans for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the food distribution program. On the basis of a successful pilot and a review of the government’s existing efforts to improve the system, WFP was able to develop a best-practice approach and offer expertise in several critical areas. WFP’s model is built on advances in a biometric technology that identifies eligible beneficiaries on the basis of their fingerprints, irises, and faces. This method helps ensure that food goes to the intended target populations. India’s government appreciates WFP’s support and expertise and has shared the solution with several state governments, allowing WFP to start working with states to implement its recommended model.

By adopting similar strategies, rethinking how they operate, and working in partnership with MIC governments, international aid agencies can achieve far greater scale and impact—and play a far more meaningful role in the global fight against poverty.