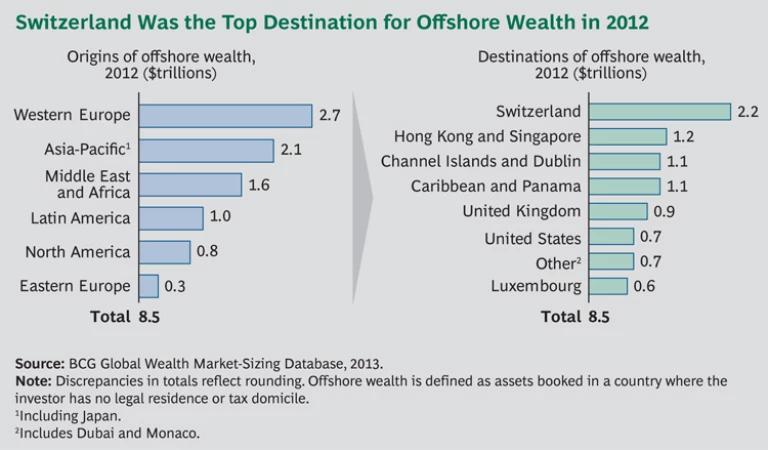

Offshore wealth, defined as assets booked in a country where the investor has no legal residence or tax domicile, rose by 6.1 percent in 2012 to $8.5 trillion, with Western Europe the predominant source and Switzerland the most popular destination. (See the exhibit below.) Despite this increase, stronger growth in onshore wealth led to a slight decline—to 6.3 percent from 6.4 percent, compared with 2011—in offshore wealth’s share of global private wealth. Offshore wealth is projected to increase moderately over the next five years, reaching $11.2 trillion by the end of 2017.

Global Wealth 2013

- Maintaining Momentum in a Complex World

- Trends in Offshore Wealth

- Wealth Management in 2020: A Call to Action

The offshore model remains viable because wealth management clients—particularly those in the high-net-worth (HNW) segment (with at least $1 million in wealth) and the ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) segment (with more than $100 million)—will continue to seek diversification, along with broad private-banking capabilities, specialized expertise, high-quality service, discretion, and domiciles with relatively high levels of economic and political stability. In fact, some wealth that had previously been repatriated, notably by investors based in Western European countries, has partly flowed back offshore owing to the highly differentiated value propositions that offshore domiciles can provide.

Challenges for Offshore Centers

The evolving investment needs of the wealthy—and their ongoing interest in diversifying offshore—do not, however, change the fact that offshore wealth management as an industry remains under intense and increasing pressure, particularly from tax authorities in the U.S. and Western Europe. In challenging fiscal times, it is not surprising to see governments placing perceived tax havens under a regulatory microscope and seeking to obtain information on depositors in the hope of minimizing tax evasion and maximizing tax revenues. Indeed, many European countries have agreed to share citizens’ bank-account and tax data, and U.S. tax authorities, through the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), have become much more aggressive in tracking the foreign accounts of U.S. citizens.

It is against this backdrop that offshore centers must position themselves not only as possessing skills and expertise that cannot easily be found onshore but also as embracing full transparency and integrity. Larger centers such as Singapore are already touting their reputations as trusted financial centers—for example, by revising tax treaties with other countries—and smaller offshore centers may need to make similar moves.

It is also important to note that sophisticated onshore-banking offerings are improving, particularly in RDEs. Local institutions are improving their private-banking capabilities, and international players are strengthening their presence in these markets. Such developments can potentially favor a trend toward onshore solutions for RDE-based investors. Also, as political and economic stability increases in some parts of the developing world, fewer investors may seek offshore solutions for security reasons.

UHNW and HNW client segments hold the bulk of today’s offshore money. And although these segments will invest part of their new money onshore, they will continue to seek diversified solutions, ensuring that some new wealth will continue to flow offshore. There is limited offshore growth potential from other wealth segments, which for the most part will seek improved onshore-banking offerings.

Sources and Destinations of New Offshore Wealth

Since existing wealth in offshore centers will likely remain fairly static in the coming years, the battle for leadership in offshore centers will largely be determined by the ability to attract new offshore wealth. Over the next five years, projected offshore wealth created globally will come largely from investors in Asia-Pacific ($1.4 trillion), Latin America ($0.5 trillion), the Middle East and Africa (MEA, $0.5 trillion), and Eastern Europe ($0.2 trillion).

Asia-Pacific offshore centers such as Singapore and Hong Kong are expected to receive most of the newly created wealth in the region that finds its way offshore. Similarly, offshore centers in the Caribbean region will benefit most from new offshore wealth created in Latin America, as will Miami-based U.S. and Latin American banks. European offshore centers are expected to profit most from offshore wealth created in Eastern Europe and MEA.

Overall, Asia-Pacific offshore centers will become more prominent. They are projected to hold roughly 18 percent of global offshore wealth by the end of 2017, compared with 15 percent in 2012, with European offshore centers dropping slightly from 58 percent to about 55 percent—still more than half the global total. The share of offshore centers in the U.S. and the Caribbean region will remain steady at around 20 percent, since they are expected to attract a fair share of new offshore wealth as well.

Switzerland is expected to remain the largest single offshore center globally, with about 25 percent of total offshore wealth by the end of 2017, compared with 26 percent in 2012. Singapore, in second place, is expected to increase its share from 10 percent to around 12 percent.

In order to become or remain leading offshore players, private banks will have to adjust to the current trends by building local presences, developing more sophisticated offerings, and adapting to regulatory requirements. They must also focus on the regions where the most new offshore wealth will be created—and they must be ultratransparent. Last but not least, they must focus on the UHNW and HNW segments, which will be the primary sources of new offshore wealth.