There is a massive gap between the need for infrastructure investment around the world and the ability of governments to pay for those investments. Public-private partnerships, in which the private sector builds, controls, and operates infrastructure projects subject to strict government oversight and regulation, can help bridge that gap.

Read more on this topic

Bridging the Gap

- Meeting the Infrastructure Challenge with Public-Private Partnerships

- How the Public Sector Can Drive Successful Public-Private Partnerships

- The Private Sector’s Strategy for Managing the Risks of Public-Private Partnerships

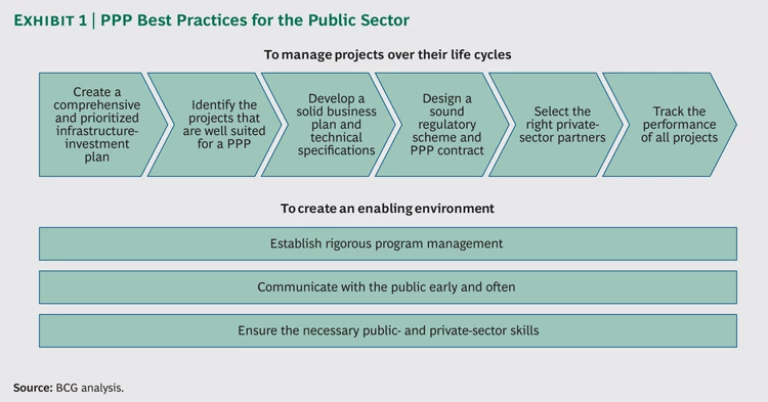

These partnerships, however, are often fraught with difficulty. Understanding what differentiates successful PPPs from failures is crucial for mitigating problems. Drawing on extensive work over the past decade, BCG has identified a series of best practices to help leaders successfully design and implement such partnerships. In addition to embracing these best practices, public-sector leaders must also address another critical—but often overlooked—driver of success: creating an environment that allows PPPs to succeed. This includes securing the right project-management expertise within the government and employing policies that support the growth of a robust private sector so that partners in both sectors have the right skills to make PPPs work. (See Exhibit 1.)

Best Practices Throughout a Project’s Life Cycle

Fully realizing a PPP’s potential requires focus and discipline every step of the way. Employing the following proven best practices along the entire life cycle of an infrastructure investment project, from project prioritization to rigorous contract monitoring, will help public-sector leaders avoid many of the worst potential traps.

Create a Comprehensive and Prioritized Infrastructure-Investment Plan

The first order of business in infrastructure investment is to make sure that the right projects are being green-lighted; this is especially important in today’s budget-constrained environment. Rather than start with a series of one-off projects, therefore, governments should devise a well-thought-out infrastructure master plan that will produce a transparent pipeline of projects. The plan should be based on a long-term agenda for economic development and must factor in the strategic infrastructure investments that should be funded to make the economic vision achievable. The most effective master plans will have clear targets for improvement in everything from roads to renewable-energy generation and will have been crafted with input from all crucial constituencies, including citizens and business leaders.

Several countries have employed this systematic approach. The Indonesian government, for example, has developed a pipeline of infrastructure projects based on its Masterplan for Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011–2025. The blueprint outlines how Indonesia will transform into an advanced economy over a period of 15 years, and it calls for developing six “economic corridors”—regions that focus on specific industries. Investment projects, then, are developed based on the type of infrastructure, such as roads or ports, that would be needed to support those industries.

Locking down new infrastructure projects to address a country’s needs and goals is obviously important. But just as important is determining whether upgrades to existing infrastructure could deliver the same payoff. Sometimes relatively simple improvements to an existing infrastructure asset can significantly increase capacity in less time and for less money than would be required for complex new projects. The operator of an airport in Italy, for example, redesigned the facility’s tariff scheme to motivate users to take off and land during less busy periods and to favor large airplanes—a move to increase the throughput of the airport’s limited runway capacity. In the United States, the government has been able to avoid making improvements to its aging electricity transmission and distribution grid by establishing the largest global market for demand response. Under this approach, energy-intensive businesses, such as commercial refrigeration facilities, accept a payment in return for temporarily shifting some of their electricity use during peak demand times. The resulting elasticity of demand in the power sector limits the need for investments to handle absolute peak levels.

Identify Projects That Are Well-suited for a PPP

Once an infrastructure project has been selected, the key question is whether it should be a public-sector-only venture or if the private sector should play a role. That decision must be based on an objective analysis of the cost and benefits to the taxpayer of both approaches.

But such an analysis, of course, is easier said than done. Many countries do not conduct these assessments in any systematic way. And even when they try, they often encounter significant stumbling blocks, including lack of expertise, a dearth of solid data, and inconsistency in the way that key assumptions in the analysis are made. Such assessments have frequently been criticized later on for unduly favoring PPPs.

Governments need to invest in three areas to ensure that they can evaluate projects with the necessary rigor. First, they should train the right people and develop the appropriate systems for conducting these evaluations. One approach is to create new units within a government that have the experience and tools to conduct these analyses. Initially, it may make sense to tap outside experts to lead the effort while training in-house staff along the way.

Second, governments must develop benchmark databases that collect cost information on both public and PPP infrastructure projects. This information, which should include not only the capital expenditures for developing a project but also the cost of operating the project over its life cycle, will drive the projected cost analysis of similar projects. An Asia-Pacific government developed a database of road construction projects for just this purpose.

And third, governments need to develop standardized methodologies for making these assessments and identify a source of common key assumptions, such as what the financing costs would look like under a public-sector approach versus a private-sector approach.

Develop a Sound Business Plan and Technical Specifications

Once the numbers show that a PPP makes sense for a particular infrastructure project, developers must address two key areas. The first is the business plan, which should include considerations such as how much traffic a new road is projected to carry or what ancillary revenue sources can be tapped. The second is the actual technical specifications of the project. These specifications are determined by the key requirements of the asset, such as the desired maximum passenger capacity of a new railway system or how fast the trains that travel on it must be able to go. Failure to plan effectively on either front can lead to major problems, including long—even indefinite—delays in construction or difficulties once the project is operational.

Crafting a sound business plan requires avoiding some common stumbling blocks, such as overestimating demand. A 2005 analysis of 104 toll-road projects by Standard & Poor’s

The various regulatory and legal hurdles that a project must clear can present additional complications. The hurdles include obtaining environmental, operating, and right-of-way permits; acquiring land; and establishing the road or railway networks needed to access and support an infrastructure project. Failing to promptly sort out these prerequisites can cause interminable delays and lead to soaring costs as resources are tied up in unproductive assets for extended periods. Projects in which the public sector takes the lead on regulatory and legal aspects tend to run more smoothly, since the government typically has more control over them. In Indonesia, for example, the government must complete all land acquisition for a PPP project before a private-sector partner can be selected.

Technical specifications can also derail a project. A common problem is to focus primarily on how the project will be constructed (input-based specifications) rather than on the performance and capacity of the completed asset (output-based specifications). While focusing on input-based specifications provides comparability across different private-sector bids and ensures that public-sector design concerns will be taken into account, doing so limits the ability of the private sector to innovate and propose alternative, potentially more cost-effective, solutions.

This point was not lost on the developers of a PPP for a convention center in India. In setting requirements for the project, the government specified only one primary output requirement: the minimum capacity of the convention hall. The private sector then came up with a design that not only met the goal but also included a way to integrate commercial opportunities, such as food and beverage purveyors and hotels. To take another example, consider the advantages that might accrue if the proposal for an urban transport corridor called for a broad, output-based specification of the number of passengers that the corridor must be able to handle rather than a more restricted specification. In that case, the private-sector company could then determine what kind of vehicle—bus or tram, for example—would be best suited for the project.

Another problem is so-called gold plating, where designers augment a project’s performance requirements beyond what is really needed. Often they do so either because they want performance to err on the side of exceeding expectations rather than failing to meet them or because they lack an understanding of how certain changes to the design will inflate costs.

To avoid this trap, designers need to clearly examine the tradeoffs between enhanced performance capabilities and the increased costs of those features over the life cycle of a project. And there should be a strict process for controlling changes to the specifications throughout design and construction. Private mining firms that have invested heavily in port, railway, and road projects, for example, have saved millions of dollars after closely comparing project specifications with actual needs. Consider the savings, for instance, if initial plans call for service access roads on both sides of a railway line, but a cost-benefit analysis determines that a road on only one side would be sufficient.

Involving experts from the private sector early on can help in vetting both the business plan and the technical specifications of a project. Before sending a proposed PPP out for bids to the private sector, government planners should have candid conversations with companies that could potentially deliver such projects. Their feedback may make a project plan more cost efficient.

Design a Sound Regulatory Scheme and PPP Contract

The details concerning a physical asset—a road or bridge, for instance—constitute only half the equation. The other critical element of a PPP comprises the regulatory structure and the contract details that make up the ground rules for everything from pricing, to risk allocation between the private and the public sector, to how investment requirements are set. Flawed regulatory models, which often fail to create an effective balance of risk between private and public partners, can deter investors, cause major problems once a project has become operational, and damage a government’s prospects for creating future PPPs.

To ensure that a regulatory scheme is sound, designers should seek input from key groups that have a stake in the project. Developers of the regulations for an Asian airport, for example, made sure to involve a group of diverse stakeholders in workshops and interviews. The stakeholders included users of the new asset, government ministries with oversight of the sector, and organizations—both public and private—engaged in similar projects. Since initial sessions focused on the key objectives and basic principles of the regulatory arrangement, planners avoided getting bogged down in minutiae, such as how pricing or service levels would be set. The agreed-upon principles of the broad regulatory structure then served as guidelines for later development of the regulatory details.

External regulation benchmarking can help get a PPP off to a good start. Creating effective regulations involves choosing among many different options, such as how and when companies will be reimbursed for future expansion and upgrade investments. Understanding the available options and studying how effective they have proven to be in other situations, therefore, is critical.

Investments in electricity and gas networks, for example, are strongly influenced by the tariff regulation, which determines the return on the investments. Governments, therefore, need to carefully assess the impact of tariff regulation on network quality, on the nation’s GDP (which rises when investments increase), and on affordable end-user prices. Moreover, when setting up and regularly reviewing the key parameters of the regulation framework, governments should conduct broad benchmarking of international options and assess the impacts that have resulted from implementing those options.

Allocating risk between the public sector and the private sector is a fundamental element of any regulatory and contract design. Generally, the idea is to assign a specific risk to the partner that is better equipped to handle it. Often, this is easy to determine. Construction risks, for example, are typically better managed by companies in the private sector that have extensive experience managing large construction projects, while the risk of available network access (such as a road that provides access to a port) can be better controlled by the public sector, which usually governs those systems. Assigning other risks, however, may depend on the specific context or the results of negotiation. Volume risks or macro risks (such as inflation, exchange rates, or a force majeure), for example, can be allocated to either the private sector or the public sector—or even be shared by the two.

Because PPPs are long-term contracts, certain risks will materialize only after a number of years. It is usually best to apportion those risks, at least to some degree, with provisions for sharing upsides and downsides in areas such as core and ancillary business revenues, financing costs, and commodity costs. This apportionment can take different forms, such as sharing every dollar gained and lost or assigning all risks and benefits to the private sector but capping the total to avoid excessive gains or losses. Such provisions often reduce the need for painful renegotiations.

Another critical element is balancing the need to safeguard the public’s interests with the need to attract—and hold on to—private-sector financing. Since many infrastructure projects constitute significant monopolistic public assets, the government often wants to be able to intervene to protect the public’s interests—for example by mandating investments that will be critical for satisfying the future demands of users. Provisions in the contract should allow for safeguarding only when absolutely necessary and then balance that constraint with appropriate rewards for the private sector.

Consider a termination clause often included in airport concession agreements, for instance, which gives the state the right to take over the facility if the operator doesn’t meet certain levels of performance. The operator, in turn, is protected from politicized or opportunistic evocations of the clause by being guaranteed a fixed period, usually 12 to 18 months, during which the company can try to fix the performance problems. What’s more, even if the operator fails to remedy the problems and the contract is terminated, the company must be compensated adequately. Typically that compensation equals the fair market value of the asset minus some penalty for the poor performance, with the figures predetermined by a previously agreed-upon methodology.

Finally, the government must be very clear about whether or not it intends to initiate new projects that may compete with the current project at some point in the future. While the government may view the construction of competing facilities as a way to exact better performance from operators, such a move would also reduce the return that those operators earn. Not surprisingly, private-sector partners would want to pay less for the right to operate an asset under those conditions than they would for projects where freedom from future competition is guaranteed. Thus the government needs to decide, from the start, whether the primary goal is to preserve some flexibility down the road or to garner the highest possible price from the private-sector partner. (For further details on economic regulation, see “Built to Last: A Win-Win Approach to Regulating Public-Private Partnerships,” September 2012.)

Select the Right Private-Sector Partners

Finding the right partner is not a matter of simply putting a contract out for bid and waiting for proposals. Governments must create a clear, competitive, and transparent process that encourages participation from many potential private-sector partners. That means being very clear about what the requirements are, including the timeline for the selection, the milestones that must be reached during the bidding process, and the criteria on which bids will be judged. Too often, bidders don’t know which factors are the most important in selecting a winner. Running the selection process in such a professional manner not only ensures a large pool of well-qualified bidders but also lays the groundwork for a productive relationship with the winner.

To attract as many qualified bidders as possible, the government should actively seek out domestic and international bidders. In addition, the bidding process should start with a preselection round that does not require bidders to pony up a steep investment. Given that the tab for putting in a formal bid may top $10 million, many companies won’t participate if the contract size is too small or their chance of winning too slim. The initial round should draw a large pool of applicants that make a preliminary bid, and then a smaller group, often three to five companies, should be selected to move ahead with a final, detailed bid.

The evaluation of those bids must be conducted by an experienced team, which may comprise a mix of government officials and outside experts. The team should follow the bidding rules strictly, and the process should be as transparent and public as possible. Failure in either regard will often lead to contested outcomes. Case in point: In India in 2005, preliminary contract awards for the modernization of the Delhi and Mumbai airports were rejected not once, but twice. A board established to look into the matter found, among other things, that there were technical flaws in the evaluation of the bids and that one bidder was treated more favorably than others.

Finally, governments must protect against the tendency among some bidders to low-ball their offer. Some companies deliberately propose an initial price that is highly favorable to the government but then attempt to renegotiate the arrangement down the road. To avoid this, selection processes should not focus exclusively on price. Instead, they should use criteria that take into account the capabilities and reputation of the potential private-sector partner. This is particularly critical in situations where the infrastructure asset will have a monopolistic market position. In addition, imposing common demand assumptions, applying strict prequalification criteria for bidders, and passing legislation can also help protect against overbidding. A law recently enacted in Colombia, for example, requires that a project be put out for bid again if, under the first deal, the government would need to increase its funding contribution by more than 20 percent above the original plan.

Track the Performance of All Projects

PPPs are long-term partnerships that will often last more than 20 years, so keeping a close watch on how well the operation of the project is going is critical. A government should dedicate resources to this effort and establish a team to monitor performance over time. This entails identifying the set of sector-specific KPIs that should be tracked, such as the System Average Interruption Duration Index (SAIDI), which is used to track the availability of electric power for consumers. Monitoring KPIs through a risk management system will allow the contract team or regulating authority to spot problems early on and take steps (which should already have been outlined in a contingency plan) to remedy the situation.

Even with a well-thought-out contingency plan, however, making changes to a PPP agreement may be necessary. After all, it is impossible to account for every potential development in advance. At a minimum, however, the contract should spell out what sorts of events trigger renegotiation, exactly how renegotiation will be conducted, and how disputes will be resolved.

In an Asian country, for example, an airport regulation clearly lays out the process for resolving conflicts between the airport and the airlines and between the airport and the civil aviation authority. In both cases, an arbiter will first assess whether or not a complaint requires investigation. If it does, the arbiter may appoint an independent advisory panel for appeals—with the arbiter covering the cost of that panel—to recommend a decision. The entire process aims for a swift resolution: within ten to 13 weeks.

One of the most valuable—though frequently overlooked—steps in the PPP process is determining whether a partnership is delivering the expected value for money and what has worked, or not worked, so far. Governments should allocate resources for these analyses, which can start as early as one or two years after a PPP begins operating. (Eventually an evaluation across the entire life cycle of the project will be essential.) Questions such as whether the project was designed correctly, whether demand fell into expected ranges, and whether renegotiation was required should be answered with an eye toward improving the future structure of PPPs.

Cultivating an Enabling Environment

Governments cannot execute best practices effectively without the right resources and expertise. These include proven program-management skills for driving the entire PPP process, effective communications strategies for managing potentially controversial projects, and legal and institutional frameworks that pave the way for the partnerships. We have identified three crucial steps that governments must take to create the right environment for supporting and driving PPPs.

Establish Rigorous Program Management

Setting up a PPP is a massively complex undertaking that involves large numbers of people—from government officials to engineering experts to financial and legal advisors. At the same time, multiple work streams must be managed, and systems must be created for tracking performance. It is crucial to use tools and methodologies, such as rigorous program management (RPM), to direct the entire effort effectively.

RPM drives three crucial elements of the PPP effort. First, it ensures sound governance, including the establishment of a fast and effective decision-making process involving important stakeholders, the creation of a program management office to drive and control the overall process, and the definition of a single point of accountability for each work stream. Second, it ensures transparency regarding the project’s status by requiring monitoring of its most critical elements. A standardized, exceptions-based reporting system, for instance, can identify anomalies that may be indicative of a significant problem. And third, it identifies potential stumbling blocks early in the process.

Communicate with the Public Early and Often

Almost every infrastructure project will encounter criticism, often from people living near the proposed site. A public uproar is most likely to occur when consumers are being required to pay for services that were previously free or subsidized, as was the case with the M6, the first toll highway in the United Kingdom. In fact, that project faced so much public opposition that it was delayed by many years.

A proactive communications plan that makes a solid case for the PPP while giving concerned citizens a voice in the process can help mitigate criticism. The plan should highlight favorable case studies and explain the benefits that underscore the value of the project. It should also include an explanation of how the government will protect the public’s interests, particularly with regard to safety, environmental, and financial concerns. For example, the key to overcoming resistance to user charges for a new roadway is to demonstrate that travelers will enjoy a clear improvement in quality (fewer traffic jams at rush hour and better driving conditions, thanks to a larger, freshly paved road). While this process cannot address every issue or demand raised by the public, it does help smooth the way when people see that their concerns are being heard and sincerely considered. Too often, the importance of this process is overlooked, and communications efforts are allocated little in the way of resources or professional planning.

Ensure the Necessary Public- and Private-Sector Skills

For a PPP to succeed, the government needs to have a series of key levers in place. These include the in-house skills to manage the process, the funds to pay for the upfront costs of preparing and developing the partnerships, and the appropriate legal frameworks and regulatory institutions to make the project feasible. Securing these levers can be particularly challenging in emerging markets, where government institutions may not be well established and, in some cases, may also be starved for resources. Creating a PPP unit, which serves as a center for PPP expertise in a country, can be most helpful for building expertise. (See “The Value of PPP Units.”)

The Value of PPP Units

PPP units come in different forms with varying responsibilities. Some are run by the government, while others are controlled by nongovernmental organizations. Infrastructure Australia, for example, was established by the Australian government to develop national PPP guidelines and frameworks, to help prioritize infrastructure investments for the central government, to provide advice on policy and regulation, and to promote the Australian PPP market at the federal level. Its activities are complemented by state-level PPP units, such as Partnerships Victoria, that provide technical assistance for specific projects.

Some PPP units have not quite become the “islands of excellence” that governments may have hoped they would, but their efforts offer valuable lessons nonetheless. First, PPP units should be crafted with a focus on making up for whatever shortcomings may exist in a government’s skill set, such as a weakness in financial modeling or in drafting PPP contracts. And second, a PPP unit should be allied with an existing, politically powerful organization—often the treasury department—in order to give the unit the attention and political clout it will need. Centralizing PPP experience upgrades and consolidates scattered, subcritical skills and helps a country improve its capability, guidelines, and processes across the board.

At the same time, it is important to recognize that PPPs aren’t cheap. To create a viable commercial and technical plan that is likely to attract experienced private-sector bidders and result in a fair shake for taxpayers, governments must often tap outside experts and advisors. The tab for such feasibility and project-structuring work regularly amounts to 2 to 5 percent of the total capital expenditure for a project. Budget-constrained governments often either do not have the funds to pay for that upfront investment or their budget allocation is biased toward construction rather than preparation.

Therefore, project preparation facilities, which consist of funds specifically set aside to explore the feasibility of PPPs and to prepare them rigorously, can make a big difference. A government in Southeast Asia established such a facility as part of an overall effort to enhance its PPP capabilities. The facility was designed to ensure sustainable funding for the upfront preparation of PPPs and is currently being used to fund two of the country’s high-priority infrastructure projects.

PPPs need legal and regulatory support as well. For example, there must be laws on the books that grant the government the ability to form partnerships with companies in the private sector. And independent regulatory institutions, which are scarce in many emerging markets, must be established and staffed to oversee projects throughout their life cycles.

Less obvious, but also important, is the effort that the government should make to encourage the growth of strong private-sector partners in the first place. To flourish, PPPs need a robust private sector that harbors engineering expertise and skilled labor. Governments, therefore, should promote the development of that market, whether by boosting education, implementing policies to encourage foreign direct investment, or creating anticorruption initiatives.