Every idea, no matter how ingenious or successful, will eventually need to be replaced with a new one. But business leaders, as human beings above all, tend to cling to their existing ideas, beliefs, and other mental models—or what we call boxes—longer than they should. For instance, Henry Ford famously insisted on continuing to manufacture the Model T long after his competitors were creating dazzling new automobiles that significantly cannibalized sales of his once best-selling car.

When Apple first created its highly disruptive, history-making iPhone, the company unleashed years of innovation not just in its phone offerings, but in a seemingly infinite stream of related accessories and applications. The release this week of Apple’s long-awaited iPhone 5C and 5S should offer business leaders everywhere a vivid reminder of the distinction between paradigm-shifting “creativity” and the “innovation” that often follows. Creativity and innovation are two separate processes—both important, but not identical.

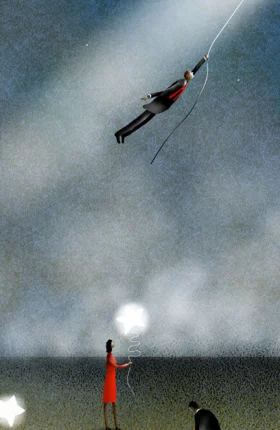

Creativity can be defined as people’s ability to change their perception of reality; by doing so, they can then create new ideas, hypotheses, approaches, and other “boxes.” Apple couldn’t come up with the original iPod, for example, until its leaders changed their mental boxes regarding what a portable music player was—from the Sony Walkman to one associated with a broader ecosystem. The iPhone was not the first mobile phone, but it fundamentally changed the box of what a mobile phone could be (as Apple also did with the iPad and mouse).

Innovation can be defined as a change in reality. In other words, innovation means taking an existing idea or box, such as the idea for a new product, service, or business model, and turning it into reality (for example, by manufacturing the product or implementing the business model). Once the first iPhone was developed, Apple was free to create all sorts of new features for and iterations of the iPhone and iPad—encouraging customers to change their own understanding of the products’ possibilities.

Incremental innovations—think of BIC introducing double-bladed or triple-bladed razors once they were already in the razor business—do not require the creation of a new box. But transformational innovations—such as when BIC transformed itself from a pen manufacturer to a company that makes all sorts of disposable plastic objects, including pens, razors, lighters, calling cards—do require a new box.

The development of the earliest lanterns and light bulbs was based on the assumption that “light is created by burning something.” Once this box was established, engineers innovated by trying different materials, such as various wicks or oils, to improve the quality and duration of the light. Only when Thomas Edison shifted his, and the world’s, perception to embrace a new box—that light is created by preventing something (the filament) from burning—could he then create the first incandescent light bulb.

In creating the new iPhone 5C and 5S, did leaders at Apple have to change some of their most fundamental perceptions of the company and the products and services it provides? Put differently, did Apple create a whole new box or did it use its legendary R&D skills to innovate further?

One thing is clear: no matter how robust and dominant this technology is today, eventually the iPhone and its ecosystem, and the ideas and assumptions underlying them, will need to be reexamined and replaced. And just imagine the tremendous new opportunities and offerings that Apple will provide the world when it does so!

This commentary originally appeared on HBR.org .