How would you react if you discovered that your company’s selling expenses were 30 percent, or even 50 percent, higher than those of other companies? And what would you do if you also found that your company had more back-office employees than revenue-generating sales reps, and that it was not benefiting from economies of scale typical of commercial functions in other industries? Finally, what actions would you take if your own team considered your company’s commercial capabilities too immature to meet the rapidly changing demands and buying patterns of key customers?

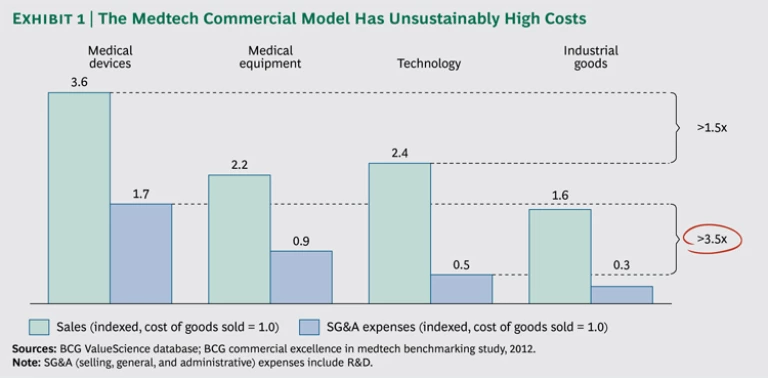

Before you answer, let this reality sink in: many medical-technology companies spend not 30 percent or 50 percent more, but 200, 300, or even 500 percent more on selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses as a percentage of the cost of goods sold than the typical technology or industrial company. (See Exhibit 1.) At the same time, the majority of medtech companies realize no economies of scale in commercial back-office operations such as marketing, human resources, and finance—meaning that as these companies grow larger, their back offices grow at the same rate. Further, in a recent BCG survey of medtech businesses, the majority of employees assessed their companies’ critical commercial functions as operating at only a basic or an intermediate level of maturity.

These findings may be hard to believe for a healthy industry, but they describe the reality at most medtech companies. Two decades of hard-earned clinical innovation have yielded attractive gross margins, but these margins mask high-cost commercial models and underdeveloped commercial skills when compared with other industries.

A Fundamental Shift in the Market

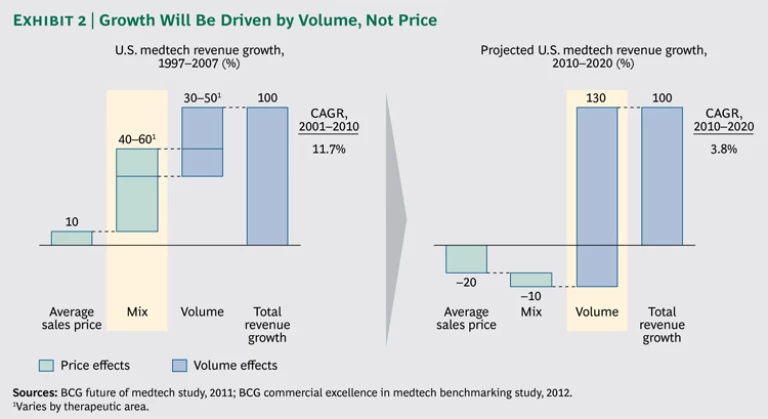

Unfortunately, the current decade (2010 through 2019) promises to be less attractive than the last for medtech companies. The growing sophistication of purchasing organizations and reimbursement authorities, combined with the weakness in the global economy and widespread government debt, are pressuring gross margins. In this context, it will be increasingly difficult for medtech companies to raise prices on existing products and achieve “mix benefits” (by selling new products at higher prices than those of the products they are meant to replace). BCG’s research indicates that margins will contract in 32 out of the 36 medtech segments reviewed, with gross margins compressing by as much as 8 percentage points in some segments.

Faced with these pressures, medtech companies might seem justified in being discouraged. But while the forces driving prices lower are intensifying, there are tailwinds driving higher unit volumes. Populations are aging in developed countries. In the United States, the federal government is pushing for universal coverage. And in China, the largest emerging market, the government has invested billions—and will continue to invest—in broader access to health care.

The bottom line: growth powered by price increases and mix benefits is giving way to unit volume growth. (See Exhibit 2.) Yet nearly all medtech companies still have a commercial organization designed for the former and unfit for the latter.

To understand where the industry is today—and where it needs to go—BCG conducted an exhaustive benchmarking study that captured commercial cost and productivity metrics across 38 medtech businesses. The study included a survey of 4,500 medtech employees in sales, key account management, marketing, reimbursement, pricing, and service functions in the U.S., the EU5 (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the U.K.), Japan, and the BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) on their companies’ commercial capabilities, as well as interviews with 80 senior executives on commercial trends and strategies. It provides a detailed snapshot of the industry today, as well as insight into the best practices deployed by the top-performing medtech companies. The study makes clear that it is possible to succeed and drive rapid profit expansion, but doing so requires moving decisively on two fronts:

- Reinventing the Commercial Model. The old model is broken—it is analogous to milkmen delivering milk in a world dominated by megastores. Companies must drastically lower costs while adjusting their go-to-market approach to match new buying processes and decision makers.

- Building Best-Practice Capabilities. Companies must move beyond traditional selling to build advantage across all critical commercial functions, including marketing focused on the value delivered by products, key account management, pricing, reimbursement, and value-added services.

The Old Model Is Broken

A number of factors are converging in health care that over time will cause gross margins in medtech to resemble those of mature industries. In addition to the downward pressure on pricing, these factors include dramatic changes in buying processes.

For some medtech businesses, purchase decisions once driven purely by individual clinicians are beginning to be made by committees of administrators, by clinicians tasked with administrative roles, and by purchasing managers with access to comprehensive information on product prices. These decisions are being made on the basis of clinical acceptability rather than individual clinician preference, measurable improvements in outcomes rather than the guidance of key opinion leaders, and even the net impact on hospital or payer profits rather than the cost of the product.

Further, sales that used to occur within a local hospital may now be made centrally to executives in a large hospital system with a different set of objectives. In the U.S., for example, how customers buy (and, therefore, how medtech companies sell) will change dramatically as providers begin to bear the risks associated with managing the total cost of a patient over his or her life. Research done by BCG suggests that the number of lives managed by such accountable care organizations in the U.S. will double or triple over the next four years, demanding that medtech companies develop value propositions designed for this new type of customer.

In addition, gaining access to markets and achieving favorable reimbursement decisions are becoming much more complicated. Government and regulatory groups, health-technology assessment authorities (such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the U.K.), private payers, and large provider organizations are demanding more evidence that premium medical devices create value—meaning that they lower total cost while improving clinical outcomes.

In Europe, for example, there is an ongoing shift in influence from hospital-level decision making to buying groups, payers, and regional as well as national market-access bodies. This requires medtech companies to develop new capabilities in contracting and tender management, in health economics, and in communicating with these new stakeholders. To complicate matters, these changes in decision making are occurring at different rates and are taking different forms across Europe, necessitating a tailored approach by market.

Take blood glucose monitoring. In years past, the diabetes care nurse or the endocrinologist had the biggest influence on a patient’s choice of meters and test strips. Companies deployed traditional sales reps to call on these clinicians one by one. Today, however, the U.S. government is starting to require local competitive bidding for Medicare-reimbursed strips. In Germany, regulators have ended reimbursement of test strips altogether for type II diabetes patients who are not on insulin, and in some regions are setting target market shares for low-cost “class B” products. Such measures have led to a dramatic decline in prices over the past three years.

The Winning Transformation

So what model do you need? Conceptually, it is quite simple to design:

- Identify who is influencing purchasing in your product categories—from market access authorities to clinicians.

- Determine what they care about and what you have to offer each stakeholder.

- Redesign sales, marketing, and other commercial capabilities and roles to reach these stakeholders with specific messages.

- Adjust your cost structure to the rate at which your products are becoming commoditized.

This roadmap is simple conceptually but difficult to get right and execute.

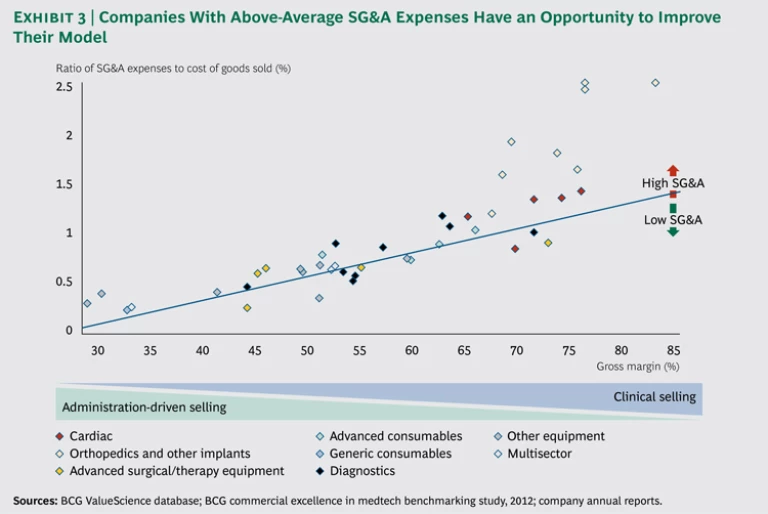

Learn from the leaders. You can begin by considering where your company is situated in terms of the correlation, shown in Exhibit 3, between gross margin and SG&A expenses at medtech companies today. At the upper right of the graph are companies with high-touch “clinical” selling models, including, for example, companies that sell orthopedic implants and cardiac devices. These sectors have the highest-cost commercial models. At the bottom left are device, equipment, and supply companies with lower-cost “administration driven,” or “contract,” models. The companies in the middle generally use a mix of these two selling models.

Companies that lie above the line on the graph have higher-cost commercial models than other companies with similar gross margins and should consider implementing rapid, short-term efficiency measures. But for companies with high-cost operating models in the upper-right portion, simple efficiency measures will not be enough. They will need a fundamentally new commercial model as margin pressures come to bear. Higher-cost operators should expect gross margins to contract in the coming years and may find some clues about how to adapt by looking at companies with lower-cost operating models in the lower-left section of the graph. For companies already situated on the lower left, it might be instructive to look at innovative models in medtech and in other, more mature industries.

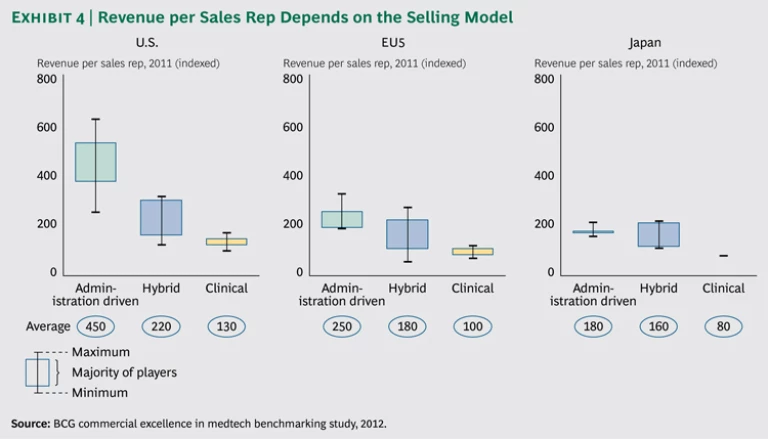

It is also worth examining two subcomponents of costs: the sales force and back-office expenses. The BCG benchmarking study enabled an assessment of the sales rep productivity of various selling models. (See Exhibit 4.) Companies that primarily employ a clinician-focused model achieve revenues per sales rep that are, on average, only 30 to 50 percent those of companies with commercial models that focus on administrative decision makers. Companies using some combination of the two models have revenues per sales rep in the middle of the range, as expected.

While this pattern holds across different parts of the world, the absolute level of sales force productivity varies by region. Sales rep productivity in the U.S. is higher than in Europe, and productivity in Europe is higher than in Japan. The differences, which are larger for the administration-driven model, result from several factors, including higher price levels and the increasing consolidation of institutional hospital buying in the U.S.

When it comes to back-office operations, BCG’s benchmarking study showed that, in general, there are more employees in the back office than in the revenue-generating functions of sales and key account management. In addition, we found that many medtech companies are not exploiting economies of scale. Thus, the percentage of back-office workers at larger country organizations (the units that oversee a company’s business within a specific nation) is the same or even larger than at smaller organizations. There is a tremendous opportunity for medtech companies to reexamine and revamp how their back-office functions are managed, including centralizing some activities that are currently being done by multiple individual country organizations.

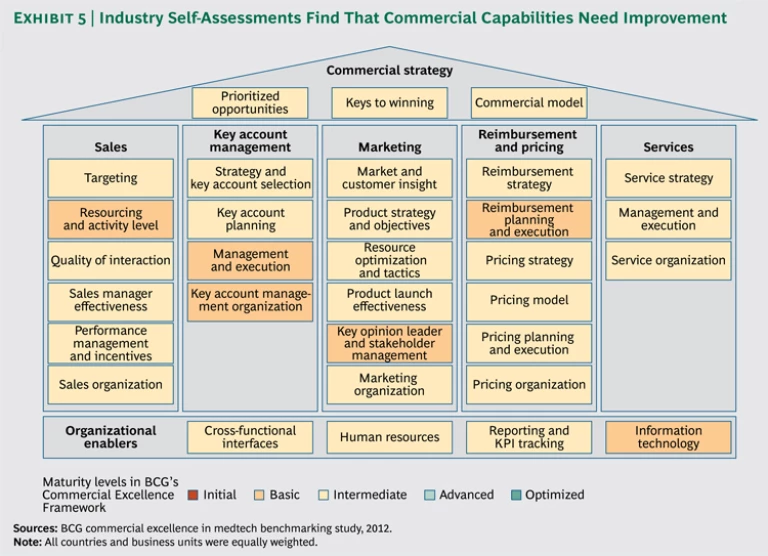

Build best-practice capabilities in sales and beyond. Medtech companies must move beyond traditional selling to build a competitive advantage across all critical commercial functions. As part of our benchmarking study, we asked more than 4,500 employees at the 38 participating medtech businesses to rate their companies on a five-point scale of maturity (initial, basic, intermediate, advanced, and optimized) across a comprehensive set of best practices captured in BCG’s Commercial Excellence Framework. (See Exhibit 5.) This framework identifies the skills and processes necessary to excel in creating the right go-to-market strategy as well as in five key functional disciplines—sales, key account management, marketing, reimbursement and pricing, and services.

The survey confirmed that the capabilities of most medtech companies have kept pace neither with changes in buying practices nor with emerging challenges in market access and reimbursement. The new market realities require a greater focus on capabilities such as communicating the value of products through marketing, establishing real partnerships with key accounts, securing reimbursement and market access, setting and negotiating pricing, and differentiating the company’s brand through value-added services.

On average, participants assessed their companies at the intermediate maturity level. And they rated multiple areas—including sales resourcing and activity level, key account management and execution, key opinion leader and stakeholder management, reimbursement, and the use of IT (such as CRM systems)—at only the basic level. Employees at just 1 of the 38 businesses assessed their company at the advanced level of maturity, while many rated their company at the basic level overall.

To help prioritize the areas requiring action, the survey asked not only for companies’ current maturity level but also for the level required to win in the market. The resulting “maturity gap,” combined with an assessment of the relative importance of the core activities within each of the five functional disciplines, clarified the key hot spots on which companies should focus. Typically, substantial improvement was required in all functions, underscoring just how great is the need for a transformation of the commercial model at many businesses.

Six Transformational Actions

Certainly there is no one-size-fits-all solution for transforming the medtech commercial model or for building best-in-class commercial capabilities. But our benchmarking study and extensive client work have led us to identify six actions that can help companies begin the journey on both fronts.

Customize your go-to-market strategy. Start with a systematic review that focuses on three key elements: prioritizing the right market segments, determining how to win in those targeted segments, and tailoring the commercial model to execute successfully.

Prioritization of market segments should be based on an in-depth assessment of market opportunities. Because of all the changes that have occurred in recent years, this can lead to substantial shifts in focus by geography, customer segment, and product category. It can even include a global rebalancing of investments—from developed to emerging markets, for example. At the local level, we often see the need for a more explicit targeting of the highest-potential customers and increased investment in the support of key accounts. The evaluation by product category can also prompt a reallocation of resources from commoditizing to differentiated products.

Next, decipher the key factors that drive success in each priority segment. This requires a deep understanding of all the stakeholders in the buying process, from market access decision makers to health care professionals. It is no longer sufficient to gain national market access and then build support for the company’s products among physicians. Winning in today’s environment requires a compelling value proposition for institutional stakeholders, from hospital procurement and formulary committees to group purchasing organizations to regional market-access bodies. In this environment, the new sources of competitive advantage are reliable health-economic data, value-added service offerings, innovative pricing models and, most important, a skilled sales force with selling abilities that go far beyond the demonstration of product features.

The final step is to tailor the commercial model according to what is required to win. The changes can be drastic, involving substantial shifts in customer coverage, such as a ramp-up in resources aimed at regional market-access decision makers and key accounts. Channel strategy may also change. A number of companies, for example, are taking steps to be closer to the patient, including hearing-instrument manufacturers that are forward-integrating into retail, dialysis-product manufacturers that are expanding into dialysis centers, and chronic-care device makers that are starting to provide home care services. Even branding may change radically, in some cases with the creation of a second, value-oriented product line.

Reinvent clinical selling. Medtech companies need to do less but more focused clinical selling and, at the same time, invest in new administrative selling capabilities to reflect the shift in decision making power in the market. Getting the clinical selling model right can yield substantial benefits in both efficiency and effectiveness. We recommend exploring several ways to “segment and target” the customer base in order to get the most out of investments in clinical selling.

First, adjust the amount of clinical selling by product line. In many categories, medtech companies have not adapted to the fact that hospitals have already shifted purchase decision making out of the hands of clinicians. Second, increase the rigor of clinician targeting, focusing only on clinicians who have real influence within their systems. Third, adjust the amount of clinical selling by type of institution. Hospital systems have strikingly different procurement practices, with some allowing the preferences of individual clinicians to drive purchasing decisions, while others employ highly centralized purchasing processes, with a committee of administrative clinicians representing the clinical viewpoint.

Given the increasingly diverse buying processes of customers, regional sales managers play a newly important role as change agents and coaches in ensuring that the right clinical selling model is deployed for each customer.

Partner with key accounts. In the medtech industry, the top 10 percent of customers can represent as much as 50 percent of the business in a given product category. And these accounts can be very profitable. While competition is often the most intense for this business, pricing for key accounts is not necessarily much lower than for smaller accounts, because these customers are often early adopters of innovative products and may be less subject to budget pressures. In addition, their experience and sophistication can mean that they require less education and support, making them less expensive to serve relative to their size. With the right focus, key-account-management programs can significantly boost returns in both the short and the long term.

However, the medtech industry is far behind other sectors when it comes to key account management. Average performers, rather than the superstars of the sales force, are often tasked with serving key accounts. In addition, key account managers are more often than not reduced to mere bundle discounters, lacking a compelling value proposition that addresses the real needs of these customers.

To turn key account management into a true competitive advantage, companies must first identify those customers that merit a new approach. This requires a detailed analysis of the business potential of specific customers and the related costs of serving them. The evaluation should also examine how ready an account is for a program aimed at creating value for both sides. The fact is that for some large accounts, a key-account-management program will simply lead to higher discounts without any increased payoff for the medtech company; in these cases, the traditional sales approach is more appropriate.

Getting key account management right can yield increased sales, reduced costs on both sides, and improved clinical outcomes. Leading medtech players have developed joint innovation programs and integrated supply chains, as well as strategic partnerships relating to private-label offerings and value-added services tailored to build customer loyalty.

Build real marketing muscle that drives home the value of products. In medtech, the sales rep has traditionally been the driver of the commercial operation, with marketing often taking a back seat. In today’s market, however, marketing must take on the primary role, developing commercial strategies and tactics based on deep market and customer insight and providing compelling value propositions to mitigate the mounting pressure on prices. At the same time, marketing must help determine the optimal allocation of commercial resources and take a more active role in orchestrating collaboration among the various commercial functions.

Building a case for the value offered by medtech products is one of the most critical jobs facing medtech companies today. Currently, companies focus mainly on the technical features of their products, rather than building a message around the advantages that those products offer in outcomes and efficiency through reduced cost of care, shorter hospital stays, or lower rates of repeat surgeries. Likewise, strategic pricing decisions are often made without drawing on market research and evidence of a product’s impact on overall health costs. Companies that use this information to craft a convincing marketing message are winning in the marketplace.

Invest in reimbursement and pricing capabilities. While reimbursement and pricing capabilities are still nascent at many medtech companies, those that have embraced these disciplines have turned them into a real advantage.

Consider the case of Medtronic in Italy. The company conducted a pilot program with the region of Lombardy to assess the value of remotely monitoring patients who have its pacemakers. The program, which is based on Medtronic’s remote-patient-monitoring service, CareLink Network, led to a substantial reduction in hospitalization rates and costs. It has been adopted by more than 220 hospitals in Italy and has tracked more than 22,000 patients so far, with 500 new patients entering the program each month.

Companies that follow this example and develop the capabilities to provide evidence of their products’ health-economic benefits, as well as local teams to influence reimbursement decisions, will see a significant—and often an immediate—increase in returns.

It is not enough to secure reimbursement for key products, however. Companies must also have the ability to establish adequate prices for their offerings. Our experience indicates that a pricing-capability-building program typically realizes 3 to 4 percentage points in improved price realization, giving a significant boost to the bottom line. Such a program usually covers the strategic aspects of list-price setting and alternative-pricing arrangements, as well as local pricing execution by the sales force in negotiations with customers or in tender situations.

Make service a differentiator—and a source of revenue. As products become commoditized, services can fill the gap by creating a differentiated overall value proposition for customers. Not surprisingly, BCG’s benchmarking study showed service revenues growing at three to four times the rate of product revenue growth—for large-equipment players as well as for small-equipment and device companies. In fact, technical services are often already among the most profitable businesses for large-equipment companies. And for device companies, services have the potential to shift the focus from product price to the value of the overall solution.

In our experience, service excellence can become a true source of competitive advantage by differentiating the product offering, providing an additional source of revenue, and reducing costs. Yet many medtech companies are not creative in developing their service offerings, instead choosing simply to match what their competitors provide.

A Call to Action

It is clear that the medtech industry is facing a period of sustained and wrenching change. The twin pressures of contracting prices and shifting decision-making processes will force companies to overhaul their commercial operations. Companies that fail to confront these changes will face a future of reduced growth and diminishing returns.

It is crucial for companies to understand where they stand today and where they need to move in the years ahead. As BCG’s benchmarking study demonstrates, the industry has significant work to do in improving the efficiency of its commercial model while strengthening its capabilities across the full spectrum of commercial excellence.

Finding the right commercial model is a challenging but a far from impossible task. There are six clear-cut steps companies can take now—steps that will help them strengthen their go-to-market strategy and improve the performance of the sales, key account management, marketing, reimbursement, pricing, and service functions. Driving such change will certainly be painful. But those that fail to make the shift—companies that continue to deploy the equivalent of milkmen in a megastore world—will be in for the most pain of all.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this publication was sponsored by BCG’s Health Care practice.

The authors would like to thank their BCG colleagues Stefanie Walther and Ralph Landolt, who managed the project team, and Carmen Binder, Cassian Gruber, Karlo Kampmann, Vera-Maria Pitot, Jennifer Progin, and Felix Wagner for their contributions to the research and analysis. In addition, they are grateful to Georg Beyer, Torben Danger, Mike Duffy, Christophe Durand, Stuart Gander, Roman Geis, Sherrie Glas, Simon Goodall, Axel Heinemann, Nicolas Kachaner, Osamu Karita, Nate Kelley, Peter Lawyer, Rachel Lee, Mark Lubkeman, Ying Luo, Abigail Moreland, Yohsuke Nishitani, Johan Öberg, David Pérez, David Ripley, Barry Rosenberg, Daniel Schroer, Ulrik Schulze, Christoph Schweizer, Vaidyanathan Srikant, Justin Toh, Stephen Waddell, John Wong, Gerd Wübbels, and Victoria Zalkin and their teams for conducting the senior-management interviews and engaging with their clients in the medtech space. Finally, they acknowledge Amy Barrett and Katie Sasser for their contributions to the development and writing of this report and Katherine Andrews, Angela DiBattista, Gina Goldstein, and Sara Strassenreiter for editing, design, and production.