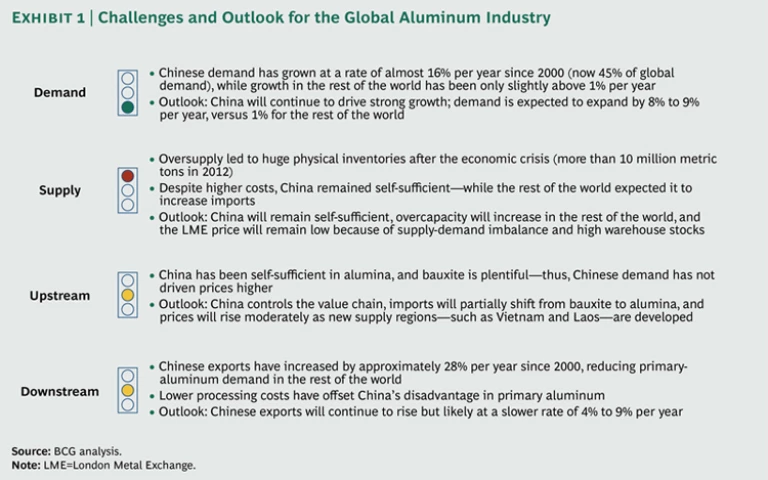

The aluminum industry has experienced a severe crisis in recent years, including a sharp decline in company valuations and profits and a depressed price for the metal. To identify the underlying causes of the current crisis, we examined the challenges and outlook for the demand and supply of primary aluminum and the upstream and downstream segments of the value chain. (See Exhibit 1.)

Read more on this topic

The Aluminum Industry CEO Agenda, 2013–2015

- The Aluminum Industry CEO Agenda, 2013–2015

- What Caused the Aluminum Industry’s Crisis?

Our analyses show that the industry’s crisis cannot be traced back to an unexpected drop in demand caused by the global economic downturn or to sudden, surprising changes in the upstream or downstream segments of the value chain. Instead, the crisis arose from the supply side, driven by China’s strategy to increase its capacity for producing primary aluminum. Producers in the rest of the world did not predict China’s moves and did not respond with sufficiently rapid strategic adjustments.

A Two-Speed World for Demand

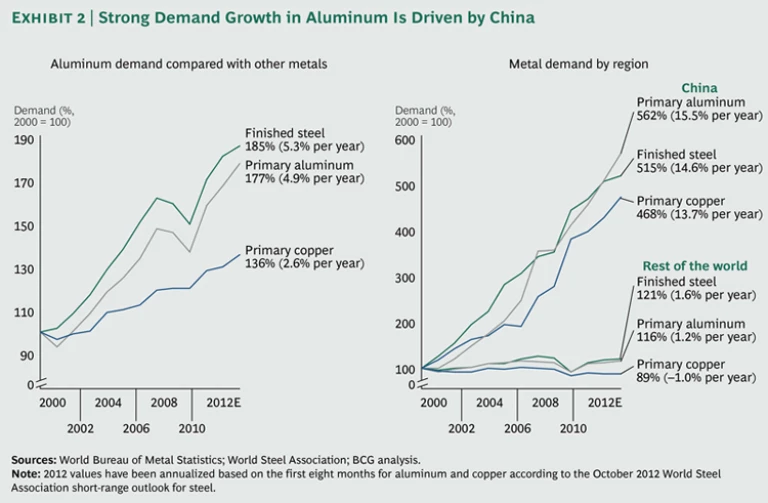

Since 2000, primary aluminum has experienced particularly strong global growth in demand—nearly 5 percent per year. This is a significantly higher rate than that of global GDP during the same period and twice as strong as the metal’s average demand growth rate of 2.4 percent during the preceding 30 years. Aluminum’s annual demand growth since the turn of the millennium has outpaced that of copper (2.6 percent) and is similar to that of finished steel (5.3 percent).

But a purely global perspective does not reveal the most critical fact about demand: global consumption has been driven almost entirely by China, resulting in a “two-speed world” of aluminum consumption. Primary-aluminum consumption in China has grown at a rate of almost 16 percent per year since 2000, while growth in the rest of the world has been only slightly above 1 percent per year. (See Exhibit 2.) The differential was especially apparent during the global financial crisis. In 2009, consumption outside China dropped by 17 percent, whereas Chinese consumption increased by 15 percent. This growth was driven by China’s massive investments in real estate and infrastructure, as well as by private consumption and exports of manufactured goods containing aluminum. As a consequence, China’s share of global aluminum demand increased from 14 percent in 2000 to 42 percent in 2011. Its share is expected to have reached approximately 45 percent in 2012. The two-speed pattern for demand in China versus the rest of the world also holds true for copper and steel.

As is the case for other basic-materials industries, the aluminum industry has enjoyed a super cycle on the demand side. But in contrast to most of its peer industries, it has largely failed to translate that demand surge into higher prices or increased profitability.

Given the substantial benefits of aluminum and its use in key growth sectors such as transportation equipment, infrastructure, and consumer products, demand is expected to remain strong in the long term. Trends such as rising fuel prices and concerns about carbon dioxide emissions, for example, are likely to accelerate the substitution of aluminum for steel in the automotive industry. And due to the strong price increase in copper, aluminum has recently begun to be used as a substitute in selected electrical applications.

We expect global primary-aluminum demand to grow at an annual rate of 4 to 5 percent during the next five to ten years. This strong growth will continue to be driven by China, where demand is expected to expand by 8 to 9 percent per year. Demand growth in the rest of the world will likely be approximately 1 percent per year. In 2017, global demand for primary aluminum will reach 55 to 57 million metric tons (MMT) according to this forecast, with China consuming 28 to 30 MMT, or 51 to 53 percent, of global demand.

China’s role as the growth engine of global aluminum demand does, in principle, present a great opportunity for the industry—but the country is also a major pain point. Its substantial increase in demand triggered the development of massive Chinese production capacity—a phenomenon that did not occur with other commodities in China. This expanding Chinese supply is at the root of the global aluminum crisis.

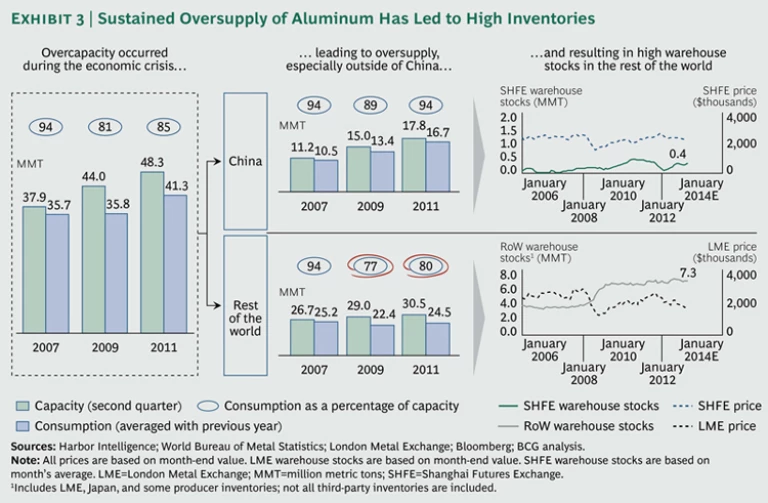

The Rapid Growth of China’s Capacity

In the second quarter of 2007, demand and supply for primary aluminum were still in balance. (See Exhibit 3.) The effective global smelting capacity was 37.9 MMT, and global consumption was 35.7 MMT, equal to 94 percent of capacity. At the height of the economic crisis in the second quarter of 2009, consumption was largely unchanged, but global capacity had increased to 44 MMT, reducing the ratio of consumption to capacity to 81 percent. Although the ratio rose to 85 percent globally in 2011, there is a stark contrast between China and the rest of the world. The ratio fully recovered to 94 percent in China, but was only 80 percent in the rest of the world.

Whereas China’s smelting capacity has increased in tandem with its aluminum consumption, supply and demand in the rest of the world continue to be severely out of balance. Instead of shutting down capacity on a large scale (and thereby stabilizing prices), smelters around the world continued to produce. As a result, huge inventories of aluminum have piled up in warehouses; 10 to 12 MMT (about 25 percent of expected 2013 global demand) is currently in storage. Increases in inventory have also been promoted by a strong

Why didn’t Western companies remove excess capacity when demand declined? Aluminum has high fixed costs, which make it difficult to shut down capacity. Smelters that lack a captive energy supply usually enter into long-term energy contracts that contain fixed off-take agreements—that is, the operator must continue to pay for energy even if it shuts down production. Regional governments often prevent smelter closures and offer subsidies in exchange for preserving jobs. In addition, high costs for shutting down and restarting operations often prevent companies from closing smelters temporarily. Finally, shutting down capacity in a global commodity business can be like a game of chicken. Because companies benefit if a competitor cuts production, they are inclined to wait for others to shut down capacity before doing so themselves.

This analysis, however, doesn’t explain why capacity outside China increased so drastically beyond demand. Although the global economic crisis was not widely predicted, the fallout from the crisis only partially explains the overcapacity. Demand growth outside China was slow even before the crisis—about 2 percent per year from 2000 through 2007.

Misjudging China’s Expansion Plans

Western aluminum companies’ most important misstep was significantly underestimating the buildup of Chinese capacity. Because China lacked sufficient amounts of high-quality bauxite and inexpensive energy, the conventional wisdom was that China would import primary aluminum to fuel the demands of its rapidly expanding downstream industry. Importing primary aluminum from regions that have a comparative advantage in smelting (such as the Middle East and Russia) seemed like the logical choice for China’s “make or buy” decision—especially because China enjoys a comparative advantage in semifinished aluminum products and downstream aluminum fabrication.

In 2000, China’s imports of primary aluminum accounted for more than 25 percent of its consumption. In anticipation of rising Chinese imports, large-scale capacity expansion occurred in other parts of the world. Yet the anticipated rise in Chinese imports did not happen. Instead, China rapidly expanded its smelting capacity. Since 2007, imports have accounted for less than 2 percent of Chinese primary-aluminum demand, except for a brief period in 2009.

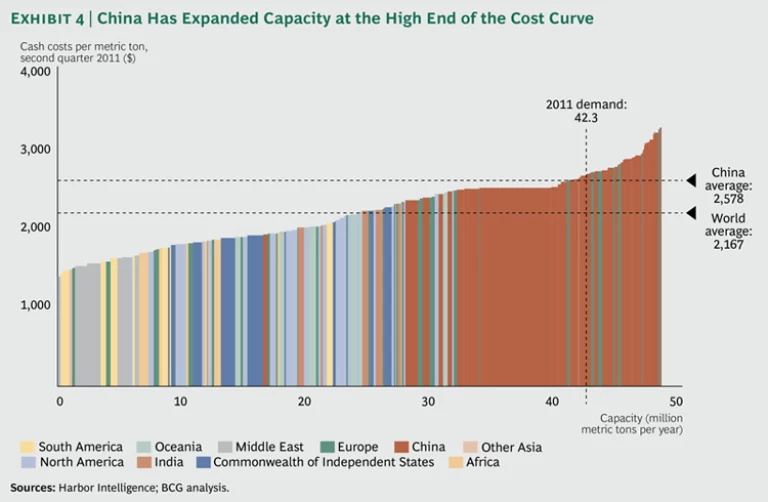

Why did China expand domestic smelting capacity so rapidly, contrary to the expectations of the international aluminum industry? China’s decision to increase capacity may be hard for observers outside the country to understand, especially because the traditionally steep costs for primary-aluminum production push most Chinese smelters to the high end of the global supply curve. (See Exhibit 4.) Yet several motivating factors helped build a strong case for the decision to increase capacity:

-

Achieving the Goal of National Self-Sufficiency. Along with steel, copper, and oil, aluminum has been a crucial ingredient in China’s rapid economic development. China’s ability to control the value chain for some of these commodities has been limited, and the government has stated that taking greater control is a top national priority. The benefits of no longer being at the mercy of a limited number of large-scale foreign suppliers of aluminum outweighed the higher costs of local production.

Moreover, this cost-benefit tradeoff will increasingly work in China’s favor. The cost premium for local production will shrink significantly during the next five years as aluminum production shifts to western Chinese provinces such as Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Ningxia. China’s west is rich in stranded coal resources and has potential for further hydroelectric power. This would allow for the establishment of captive power stations to directly supply the smelters with cheap electricity. Whereas companies in central and eastern China mainly depend on power from the public electricity grid, smelters in western regions will benefit from lower costs as well as a secure and stable energy supply. In the medium term, new smelters in western China are expected to have lower cash costs than the average smelter outside of China. In the short term, however, likely delays in the construction of the captive power stations will mean that smelters must use expensive power from the grid. Chinese companies will also need to overcome challenges such as a limited infrastructure for transporting raw materials and finished products, as well as a shortage of skilled labor.

- Fulfilling Regional Economic Development Agendas. For regional governments, the startup of an aluminum smelter can enable rapid economic growth, create jobs, and generate tax revenues. A smelter can also be a catalyst for the development of a more diverse downstream industry in the region. The planned expansion of smelting capacity in China’s western regions will not only lower the average cost of aluminum but also contribute to the economic development of remote regions, such as Xinjiang.

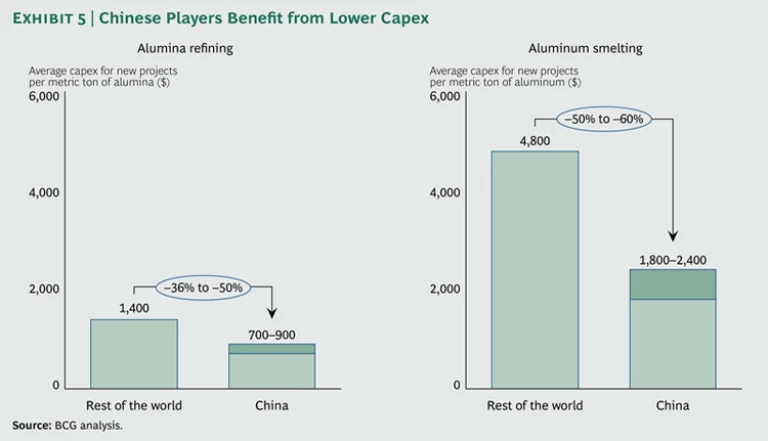

- Generating Returns from Lower Capex. Capex requirements for aluminum production in China can be much lower (by up to 60 percent) than in other countries, primarily because of lower-cost technology and construction. (See Exhibit 5.) Lower capex is an important advantage for Chinese producers, because it allows them to generate returns similar to those in other countries but from smaller margins. The situation will improve further as lower-cost capacity becomes available in western regions.

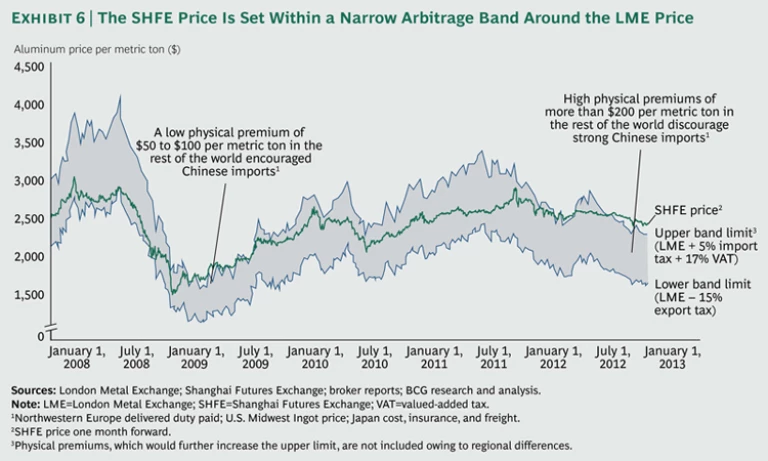

China’s unique pricing dynamics also help to explain its low import levels. Whereas the aluminum market outside of China uses the LME price, China uses its own domestic price determined at the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE). Imports are discouraged through an import tax of 5 percent, and exports are discouraged by an even higher tax of 15 percent. Within a band around the LME price (set by a value-added tax, or VAT, and import and export taxes), the SHFE price follows its own supply-demand dynamic. (See Exhibit 6.) If the SHFE price leaves this band, arbitrage opportunities through imports or exports arise. This occurred in 2009, when Chinese demand remained strong while demand in the rest of the world collapsed, resulting in imports of primary aluminum by Chinese companies. But more recently, pricing dynamics have discouraged imports.

Outside of China, capacity could increase significantly if currently planned projects go forward. While some projects will be postponed or canceled if the aluminum price remains low, others will go ahead regardless. Smelter construction often enables countries, especially those in the Middle East, to attract the downstream industry and utilize domestic low-cost gas. This allows smelters to be cash-positive even when many of them are losing money in other parts of the world. And because the extraction of shale gas outside of the Middle East has decreased export prices, the use of natural gas in local aluminum smelters has become even more attractive.

By 2017, up to 6 to 7 MMT of smelting capacity is expected to be added outside of China. This includes newly constructed capacity plus “capacity creep” (productivity improvements relating to existing capacity, estimated to be 0.5 percent per year). Without the large-scale closure of existing capacity—and assuming China remains largely self-sufficient—the total smelting capacity of 36 to 37 MMT will result in overcapacity even beyond the levels seen in the 2009 crisis.

In this scenario, the price of aluminum will remain at low levels. Any price increase from the small-scale closure of smelting capacity will be limited by high warehouse stocks, which will remain above precrisis levels for years unless China increases imports significantly.

Whether China will remain self-sufficient is thus of crucial importance to the aluminum industry in the rest of the world. It seems unlikely that the enormous warehouse stocks and excess production from outside China will find their way to China’s downstream industry. Current capacity-expansion plans put China on a course for sustained self-sufficiency and increased cost competitiveness as western China adds new capacity to the left side of the global supply curve. An additional 14 to 15 MMT of capacity (new capacity plus capacity creep) could be operational within China in 2017. Taking into account the closure of about 1 MMT of existing high-cost capacity, and assuming that primary-aluminum demand grows at 8 to 9 percent annually through 2017, China’s industry would be self-sufficient without significant overcapacity. In contrast, overcapacity in the rest of the world will likely worsen. (See Exhibit 7.)

There is, however, one fundamental challenge that could cause China to abandon its current path of self-sufficiency: an inability to secure enough bauxite and alumina to feed Chinese aluminum smelters, forcing downstream producers to import primary aluminum.

Sufficient Alumina and Bauxite Despite Resource Nationalism

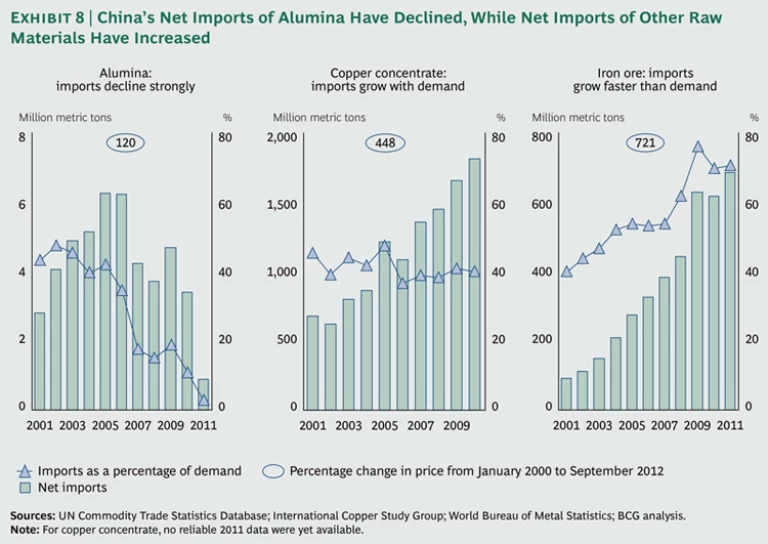

Historically, the price of alumina has been contractually linked to the price of aluminum. It is thus often assumed that the low price of aluminum is the main cause of the low price of alumina, but China’s near self-sufficiency in alumina is the more fundamental reason underlying the low prices. For other raw materials, such as copper concentrate or iron ore, China is dependent on imports from a limited number of multinational mining companies, which have been able to raise prices and reap extremely high profits. This has not been the case for alumina, China’s net imports of which have declined sharply. (See Exhibit 8.) In addition to building sufficient smelting capacity to meet domestic aluminum demand, China has had enough alumina refining capacity to lower alumina imports from levels that represented 43 percent of demand in 2001 to only 3 percent in 2011.

But China has not managed to secure self-sufficiency one step further up the value chain; the increase in domestic bauxite mining from 9 MMT in 2001 to 36 MMT in 2011 was not nearly enough to feed China’s alumina refineries, which produced more than 34 MMT of alumina in 2011. At the same time that China has had to rely increasingly on bauxite imports, Indonesia has become a major exporter of low-cost bauxite. Indonesian bauxite production increased from just 1 MMT in 2005 to 36 MMT in 2011, nearly all of which was exported to China.

Some industry observers believe that China will not be able to meet its bauxite demand because of restrictions recently announced by Indonesia. That country significantly altered the upstream market in May 2012 by introducing a 20 percent tax on bauxite exports, revoking a large number of export licenses, and threatening to ban all bauxite exports beginning in 2014. If this happens, bauxite and alumina prices will increase, raising costs for Chinese aluminum producers (but not necessarily for the major Western producers, which are largely self-sufficient in bauxite) and potentially resulting in a significant increase in Chinese imports of primary aluminum. A surge in Chinese imports would lower warehouse stocks, which would, in turn, support the LME price and rescue the aluminum industry outside of China.

This scenario is unlikely, however. What is more probable is that Indonesia will impose only a moderate version of its proposed export ban. This would allow China to gradually shift its feedstock from imported bauxite to alumina, while, in the medium to long term, it could increase imports of bauxite and alumina from owned sources in Vietnam, Laos, and other countries. China would thereby remain largely self-sufficient in primary aluminum and maintain control of the upstream value chain, causing alumina prices to increase only moderately. But even if this were the case, significant uncertainty would remain with regard to projects and expansion plans in the short to medium term.

How China Got into the Downstream Game

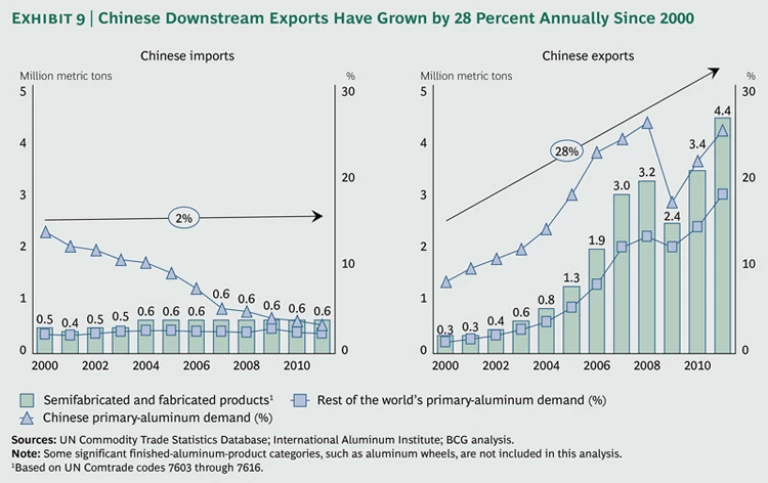

Since 2000, Chinese imports of semifabricated and selected fabricated aluminum products have remained constant in absolute terms, but they have decreased significantly relative to Chinese aluminum demand (from 14 percent in 2000 to 3 percent in 2011). This reflects the country’s ability to produce an ever-increasing range of products at low cost. For example, as recently as 2009, China had to import almost all the aluminum sheet used for beverage cans, because no Chinese company was able to produce the sheet specifications required by beverage companies. By 2011, however, 40 percent of the aluminum sheet used for beverage cans in China was produced domestically.

China’s exports of downstream products have increased even faster than domestic consumption. Exports of semifabricated and selected fabricated aluminum products have increased from 0.3 MMT in 2000 (equivalent to 10 percent of Chinese primary-aluminum demand) to 4.4 MMT in 2011 (more than 25 percent of primary-aluminum demand). This has resulted in an extraordinary 28 percent annual growth over 11 years. (See Exhibit 9.) Some downstream products of which exports have likewise increased significantly (such as automotive wheels) are not even included in these numbers because of the unavailability of sufficiently detailed data.

In fact, Chinese exports of semifabricated and fabricated products are a critical reason for the slow growth in demand for primary aluminum outside of China. If not for Chinese exports of semifabricated and fabricated products, demand for primary aluminum in the rest of the world would have been at least 4.4 MMT higher in 2011, and the compound annual growth rate of primary-aluminum demand from 2000 to 2011 would have been 2.5 percent or more instead of 1.1 percent.

Four circumstances have promoted the significant increase in Chinese downstream exports:

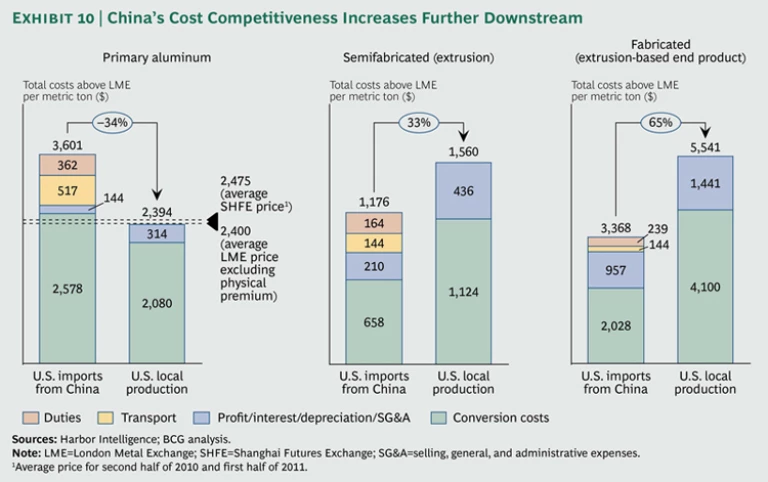

- Chinese companies have managed to maintain their low cost base. They still enjoy significant labor-cost advantages over downstream producers and fabricators in mature markets. Although labor costs represent a small share of costs in the production of primary aluminum, their share increases for semifabricated products and can be very high for many finished products. In addition to the labor cost advantage, Chinese producers often enjoy substantially lower sourcing costs for nonaluminum components and services, as well as efficient, low-cost logistics chains for exports.

- Chinese companies benefit from a huge domestic market, allowing them to generate structural advantages from economies of scale throughout their sourcing, production, and distribution ecosystem.

- While exports of primary aluminum are discouraged by export taxes, the Chinese tax system favors the export of semi-fabricated and fabricated aluminum products through a VAT rebate.

- Chinese downstream companies can enjoy significant advantages in capital expenditures and capital costs, just as upstream companies do. This allows them to sell at very competitive prices, because lower margins are required to generate equal levels of returns. Consequently, Chinese companies can often offset the energy-driven cost disadvantage in the production of primary aluminum through significant downstream cost advantages. These advantages are evident in a comparison of the costs of U.S. imports of Chinese semifabricated and fabricated products with those of products manufactured in the U.S. (See Exhibit 10.)

Chinese downstream exports are expected to grow, albeit at a slower rate of 4 to 9 percent per year through 2017. By 2017, the export volume will reach 6 to 8 MMT (excluding several finished-aluminum products). This volume is equivalent to 22 to 30 percent of the primary-aluminum demand outside of China.

As this trend continues, China is becoming an aluminum products powerhouse in areas such as aluminum-based building and construction products, infrastructure systems, transportation equipment, and consumer products. Its rise as a downstream producer could also change the competitive dynamics of many product subcategories.

China’s downstream moves will increasingly affect the world’s downstream producers. During the past few years, Chinese companies have come to dominate the global market in many categories of products that contain aluminum. For example, in equipment for wind power, an application with significant aluminum content, the top three Chinese companies control a combined 26 percent of the global market, compared with only 3 percent in 2006.

The country’s massive and increasingly cost-competitive supply base for primary aluminum will further drive growth of Chinese exports—especially of finished aluminum-based products. This growth will have a significant impact on global aluminum trade in semifinished and finished products and will cause aluminum converters and fabricators in developed markets to rethink their production and market strategies.