If there is one overriding imperative for CEOs, it is to add value to the portfolio of businesses so that the whole is worth more than the sum of its parts. Such value creation requires steering by the corporate center—whether across businesses, across regions, or across functions. But whatever form that steering takes, the corporate center must not only choose its optimal parenting strategy but also design an organization that translates that strategy’s value-creation logic into practice. Many CEOs, however, struggle to translate strategic logic into action, and as a result, many corporate centers still fall short of their full value-creation potential.

The pressure to improve the center’s value creation is unrelenting and comes from all quarters. The capital market demands constant value creation and is quick to penalize corporate shares—and CEOs—if they fail to deliver. Analysts and shareholders pay close attention to valuation discounts. They are also quick to sound the alarm when overhead cost controls appear to be weakening. They compare the corporation against competitors that demonstrate excellence and ask why the corporation can’t keep up.

Just as intense are the internal demands for constant value creation. Boards look for quick results from mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and press for corporate strategies that add value to the combined enterprise. Business units complain that the center insists that they engage in activities that impose costs and operating constraints without seeming to provide offsetting benefits. In the worst cases, these conflicts can paralyze the whole organization.

In their own ways, the markets, boards, and business units are all asking the same urgent question: What is the corporate parent doing to add value to the business units? It is no longer sufficient to assemble a corporate portfolio of good businesses. Corporate stakeholders have shifted their focus from the specific competitive advantages of individual units—such as market share, technology, or brands—to the competitive advantage at the corporate level; that is, to the parenting advantage.

Effective parenting strategies add value in many different ways. Some promote excellence in key business functions through clear guidelines; some share competencies among business units. Others improve decision quality, attract game-changing talent, or build a high-performance culture in each unit.

The Boston Consulting Group made the case for formulating an effective parenting strategy in the 2012 report, First Do No Harm: How to Be a Good Corporate Parent . Drawing on the experiences of our clients, we argued that there is no single “right” parenting strategy—what’s best for one corporation might not be suitable for even its closest and most comparable rival. Adopting general best practices is therefore of limited value. Instead, we encourage companies to systematically assess the fundamental levers by which a corporate parent creates value. (See Exhibit 1.)

Understanding how corporate parents add value is the first step in devising a parenting strategy and in reconsidering the corporate center setup. The next step is to ensure consistency among the structure, people, processes, and tools deployed to execute the strategy—including best practices that are specific to a particular parenting approach.

By analyzing the fundamental levers that companies can use to add value to their businesses, we identified six basic parenting strategies, arranging them in a taxonomy based on their degree of direct engagement with business units. In practice, corporations often follow hybrids or variants of the basic strategies. As an aid to understanding, however, we focus on the six archetypes throughout this report.

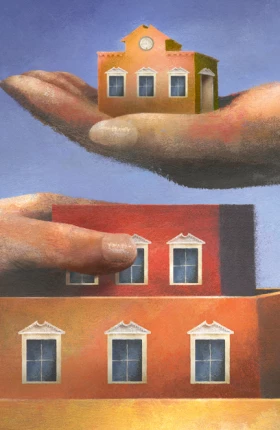

At one extreme is the hands-off owner, which, as its name implies, allows the business units virtually complete operating autonomy and requires them only to file regular statutory reports to the parent. At the other extreme is the hands-on manager, an approach that assumes all responsibility for operating the business units, which maintain autonomy only over execution. Between these extremes lie four remaining parenting strategies: financial sponsor, family builder, strategic guide, and functional leader. (See “The Six Types of Corporate Parenting.”) The optimal parenting strategy must be aligned with both the needs of the business units and the capabilities of the corporate center. For example, a more engaged parenting strategy is generally the optimal choice for the parent of a small and homogeneous portfolio of business units in mature industries. But even in these situations, an engaged strategy can backfire if the corporate center lacks the expertise required to execute it.

The Six Types of Corporate Parenting

Through its extensive experience working with clients on corporate-center design issues, BCG has identified six archetypal parenting strategies. In the business world, corporate centers are rarely “pure” examples of any single archetype—in practice, most parenting strategies are variants of the basic strategic types. But most corporate centers have, at least implicitly, a single prevailing parenting strategy, which can be assigned to one of the following six categories.

Hands-off Owner. This extremely cautious, conservative approach calls for the corporate center to engage primarily in portfolio development, adding new businesses to its portfolio and divesting others but exerting no central control over individual businesses. This strategy is, for example, typically followed by state-owned investment funds.

Financial Sponsor. The center of the financial sponsor exists primarily to provide financing advantages and governance oversight to the business units, with minimal involvement in strategy and operations. This strategy tends to be the province of traditional private-equity firms and financial holding companies.

Family Builder. The family builder maintains a limited level of engagement with the units, with its main value-creating activities confined to providing financing and developing a synergistic portfolio; that is, these corporations assemble businesses with natural synergies in, say, production and sales.1 This strategy is commonly seen at diversified fast-moving-consumer-goods companies.

Strategic Guide. The strategic guide’s center plays an active role in formulating the strategies of business units and the overall enterprise, with little engagement in other phases of the business. The primary adherents of this strategy are diversified conglomerates with large portfolios of independent, but related businesses.

Functional Leader. The main contribution to corporate value made by the functional leader comes from its promotion of functional excellence and the cost-efficient bundling of services. This strategy is most often seen at large, integrated multibusiness corporations.

Hands-on Manager. This center is the most activist corporate parent, engaged closely in the management and operations of each business unit and leaving the units responsible only for execution. This strategy is most appropriate for companies with a focused portfolio of businesses operating in mature industries.

1. BCG’s earlier report, First Do No Harm: How to Be a Good Corporate Parent, named this strategy Synergy creation.

In this latest report, we turn to the question of designing the corporate center once top management has settled on a parenting strategy. In essence, we ask what the parenting strategy implies about the optimal shape, scope, processes, and required competencies of the corporate center.

Through which activities does the center exert control? What are the lines of authority—that is, at what level do the board and corporate center interact with the business units, and where are those interactions most intense? What decision rights do the business units retain? In short, what is the mandate of each of the six parenting strategies, and what kinds of organizational design do those mandates dictate?