Cloud software is no longer a fringe market. The $15 billion global software as a service (SaaS) business is growing at about three times the rate of traditional, on-premises software. SaaS represents 12 percent of global spending on enterprise applications, and cloud-based applications are already firmly entrenched in a handful of corporate IT categories. For example, customer relationship management (CRM) and collaboration software are expected to achieve 30 and 50 percent penetration rates, respectively, in those categories by 2015.

The market for CRM software illustrates how quickly cloud players are gaining ground. According to Gartner, Salesforce.com moved from third place in 2010 to become the worldwide CRM market leader in 2012. With over $3 billion in annual revenues and an average growth rate of 30 percent per year, Salesforce.com has become a standard bearer for the power of the SaaS pricing and delivery model.

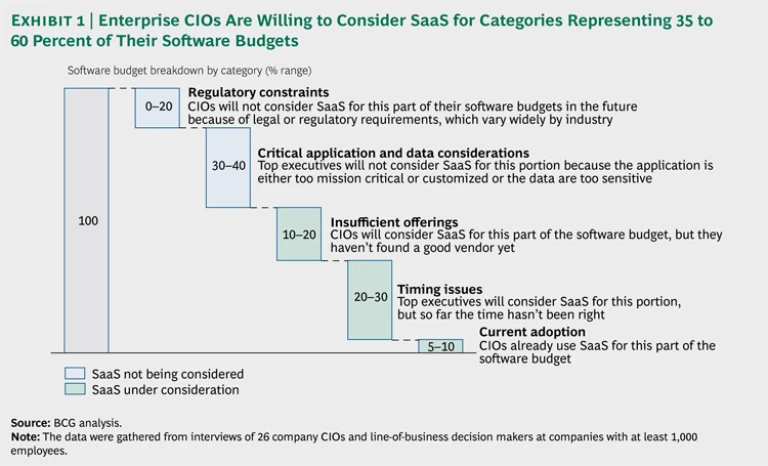

To better understand the changing landscape, we surveyed more than 80 U.S. CIOs and line-of-business software decision makers in 2012. We also conducted in-depth interviews with 26 of those decision makers and 12 SaaS vendors. SaaS applications are no longer just for midsize businesses and niche users. We found that enterprise-software decision makers have dramatically increased their consideration of cloud software. The ones we interviewed were already investing 5 to 10 percent of their software spending in SaaS solutions. More important, they were willing to consider SaaS solutions for 35 to 60 percent of their applications spending, provided that the timing and the vendor were right. (See Exhibit 1.)

In short, cloud software represents a classic disruptive innovation that could both transform the way customers buy and use software—and threaten the familiar business models of software giants.

The Business Case for Customers

Customer consideration of cloud software has increased dramatically for a number of reasons. By now, most IT and business decision makers are familiar with the appeal of the SaaS pricing model. Being able to pay for usage through a monthly subscription or “by the drink” plan is much more attractive for many customers than having to defend a large, upfront capital expenditure. Moreover, many startup cloud-software vendors offer solutions with lower entry-level pricing than that of traditional software alternatives.

Increasingly, enterprise and midmarket decision makers are looking beyond pricing to focus on other benefits of cloud-based applications. The top benefit mentioned by both CIOs and line-of-business managers was mobility: SaaS solutions are able to support multiple devices and locations. Therefore, as employee mobility increases and a bring-your-own-device approach becomes more mainstream, cloud applications are gaining favor with CIOs.

The CIOs in our survey also appreciated the flexibility that SaaS solutions provide for companies that want to quickly set up and scale a new application. Historically, IT leaders that have supported fast-growing new businesses and locations, or integrated newly acquired companies, have faced a difficult tradeoff. They could commit to costly, lengthy deployments of enterprise software systems for relatively small parts of their businesses, or they could support ad-hoc applications and tools that did not meet their standards for security and reliability. Several CIOs observed that SaaS solutions are a good compromise because they are reliable and can be deployed quickly. One customer, for example, used SaaS to support growing operations in Southeast Asia while he continued to use on-premises software in more established markets.

In discussions of cost, the price of a software license was not the only consideration for the CIOs in our survey. They went on to emphasize the value of SaaS solutions in helping them to reduce the total cost of ownership (TCO), including hardware, other software, and personnel costs. SaaS buyers reported realizing a 20 to 50 percent reduction in TCO, mostly from lower infrastructure and personnel costs.

The benefits are compelling, but disruptive new technologies are often rife with broken promises. We spoke at length with CIOs and business buyers about what helped them meet their original objectives. In the interviews, and in our own experience with clients, four themes stand out in terms of bridging the gap between promise and reality:

- Increase the variability of your hardware and software stack costs. What matters to CIOs is the total cost of hardware, software, and people needed to run an application. The more variable these costs are—such as through virtualized hardware that could be reused across applications or the ability to redeploy people to other responsibilities—the more likely the customer is to meet cost reductions.

- Get the timing right. Companies that timed their evolution toward SaaS around the consideration of a major investment in legacy software created a more compelling and feasible business case for reducing costs.

- Keep the implementation simple. In our interviews, customers that tamed their appetites for customization were most likely to deliver the new SaaS solution successfully. For example, one CIO emphasized that minimizing customization was the top reason he was able to deliver a new Salesforce.com implementation on time and under budget.

- Bring business users along every step of the way.The need to limit customization and the increasing power of business users in cloud software decisions make it even more important than usual to involve the business side in the decision-making process from the beginning. Many executives have grown accustomed to forming their opinions about cloud applications by launching their own trials with budgets that can be expensed on a credit card. IT decision makers, and the SaaS vendors they are evaluating, must work closely with a more empowered, knowledgeable business community.

IT decision makers voiced legitimate reasons, including the need for security and reliability, for staying away from SaaS solutions. But there is no longer any doubt that, for many categories, moving over to SaaS makes sense, particularly under the right business conditions and with the right IT environments.

How Vendors Can Balance the Needs of Customers and Investors

For traditional software vendors considering the switch to offering SaaS solutions, however, the picture is not as clear. While cloud software, in one form or another, has been on the market since the 1990s, SaaS has moved to the top of the agenda for many software company executives only during the past three years. Many of these executives are still grappling with the economics of cloud software and the fundamental changes that are required to serve SaaS customers profitably.

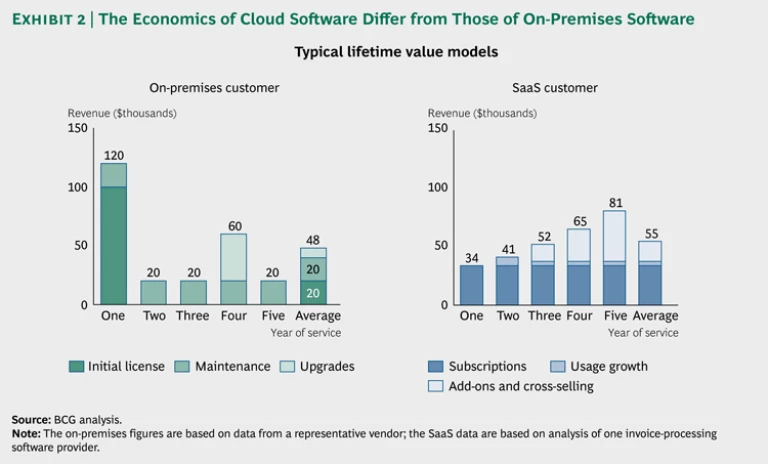

Gross margins, often above 90 percent in the traditional software world, can drop anywhere between 20 and 50 points. First-year revenues on multiyear contracts can fall 75 percent or more for enterprise software companies accustomed to selling large, upfront deals. To ensure success during this transition, software companies need to completely rethink how they package, price, and sell software to adapt to the new economics of SaaS. We believe that the following four actions will prove essential in adjusting to this new reality.

Unbundle products so they are easy to try. Think of the traditional, on-premises software offering as a “supreme” pizza. A company usually sells a large order with all the toppings—in the case of software, a host of bells and whistles that most companies don’t use. In this scenario, the company typically earns 50 to 75 percent of the product’s lifetime customer revenues during the first year after the sale.

Moving to the cloud upends that model: now a company earns only 10 to 25 percent of customer revenues in the first year—an abrupt change for a traditional company in the early years of a new product launch. (See Exhibit 2.) The bulk of the earnings comes later, as the company sells add-on modules and cross-sells additional products.

Instead of designing a product that offers all things to all people, cloud software vendors should build a relationship with each customer by selling a simple trial product that satisfies the customer’s initial needs. But they should also offer layers of extras that the customer can easily understand. For example, Salesforce.com offers five versions of its CRM service, priced anywhere from $5 to $250 per user per month. The entry-level offer, scalable subscription-pricing model, and fast Internet delivery make it easy and affordable for most businesses to try before they commit to a higher-level offering. Move the sales model from “hunting” to “farming.” In the traditional software world, the initial software sale is often a big event: A large deal can be worth millions of dollars in the first year. With cloud software, companies need a different sales model, one that emphasizes growth from a smaller initial base, a more patient and incremental building of the relationship, and a tenacious focus on customer retention. Vendors that grow profits often use volume discounts and proactive outreach to encourage customers to increase their usage, and they have a strategy for selling customers better versions of the product.

Sales skills and incentives flow from these changes. One vendor of invoicing software in our survey has an explicit sales strategy designed to grow its revenues approximately 20 percent every year, first through growth in invoices and then subsequently through cross-selling related products.

Lower your discounts to account for higher marginal costs. Another big challenge for traditional vendors moving to the cloud is that serving each customer now costs more. They have to run, or pay someone to run, a data center and ensure reliable service levels, for instance.

Having a higher cost structure changes the way companies need to think about discounting. With large enterprise software, discounts of 70 to 90 percent are not uncommon when companies really need that big deal. But for SaaS offers to be profitable, discount ranges for smaller deals should be close to zero, and they should typically be no more than 30 to 50 percent even for large, competitive deals.

Make it simple for customers to combine cloud and on-premises software. Our research and experience suggest that traditional software companies developing new SaaS offerings often pay too little attention to one of their biggest sources of competitive advantage: the integration of cloud services with existing software. Often buyers feel like they’re talking with a different company when they evaluate a traditional vendor’s SaaS solution.

Instead, traditional software makers should clearly define the benefits that existing customers would receive. For example, cloud-based applications can make a lot of sense for a new acquisition or for a business in a country where infrastructure investments aren’t feasible. They can also make sense for a customer who wants an integrated solution that bundles cloud and on-premises products. Customers should also know how SaaS offerings fit within their existing discounting agreements and how the cloud software will connect with the on-premises system. Vendors that answer these questions well can help decision makers bridge the two software worlds.

Moving into the Cloud

Migrating to the cloud represents a big step for any company. For customers, it holds the promise of flexibility and lower costs if they keep the implementation simple and have the right IT and business environments. But for traditional, on-premises software vendors, it’s a much larger leap.

The change requires companies to rethink how the organization works and how it competes. The undertaking can be difficult, and the required capabilities can be radically different from those needed in the past. But companies that get the complex interplay of moves right have a better chance of adapting to and capitalizing on the emerging cloud-based environment.

The experience of Concur, a fast-growing expense-management software company, offers a case study of how a traditional vendor moved to the cloud. Concur is a midsize business, but even the largest company considering such a move will find elements of the story relevant. Concur decided to shift its business model from on-premises to SaaS during the technology downturn at the beginning of the century. For several years, Concur’s team wrestled with the demands of a new business model and a challenging market environment. Success didn’t come overnight, but the company’s perseverance and willingness to change have rewarded investors and employees with exponential growth. Revenues went from $34 million in 2000 to $440 million in 2012, and Concur shares have outperformed the Nasdaq index 30 times during that period. By contrast, a direct competitor that was similar in size to Concur in 2000 stuck with the on-premises software model and experienced far less growth.

Stories like Concur’s illustrate both the challenges of migrating to a SaaS model and the potential rewards of making the switch successfully in the right line of business. With cloud software growing so quickly, companies cannot afford to sit out the next stage of the game. Profiting from the evolution to SaaS will require rethinking business models and taking new risks to win in an increasingly cloud-dominated market.